Automated Breast Ultrasound vs. Mammography: A Comparative Analysis for Enhanced Cancer Detection and Screening

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between traditional mammography and automated breast ultrasound (ABUS) for breast cancer screening, with a focus on implications for clinical research and diagnostic development.

Automated Breast Ultrasound vs. Mammography: A Comparative Analysis for Enhanced Cancer Detection and Screening

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between traditional mammography and automated breast ultrasound (ABUS) for breast cancer screening, with a focus on implications for clinical research and diagnostic development. It explores the foundational principles and technological evolution of both modalities, detailing their methodological applications, particularly in challenging populations like women with dense breast tissue. The analysis addresses key operational challenges and optimization strategies, including the integration of artificial intelligence and standardized protocols. Finally, it presents a rigorous validation of diagnostic performance through recent meta-analyses and large-scale trials, comparing sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy to guide future research and technological innovation in cancer diagnostics.

The Evolution of Breast Imaging: Unpacking the Core Technologies of Mammography and Automated Ultrasound

For decades, digital mammography (DM) and its advanced iteration, digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), have served as the cornerstone of population-based breast cancer screening programs worldwide. The establishment of mammography as the gold standard is predicated on extensive evidence from large, randomized trials demonstrating its efficacy in reducing breast cancer mortality. This review examines the fundamental principles underlying mammography, consolidates its well-documented strengths, and provides a critical analysis of its inherent limitations, particularly in the context of evolving imaging technologies and specific patient populations. Furthermore, within the broader thesis of comparing traditional mammography with automated breast ultrasound (ABUS) research, this analysis will objectively evaluate their respective performances based on current empirical evidence. Understanding this comparative landscape is essential for researchers and clinicians aiming to optimize screening protocols and develop next-generation diagnostic tools.

Principles of Mammography

Mammography operates on the principle of using low-dose X-rays to generate high-resolution images of the internal structure of the breast. The technique relies on differential attenuation of X-rays by various breast tissues. Adipose tissue, being less dense, attenuates fewer X-rays, appearing radiolucent or dark on the resultant image. In contrast, fibroglandular tissue and potential calcifications attenuate more radiation, presenting as radiopaque or white areas. This contrast allows radiologists to identify architectural distortions, masses, and microcalcifications that are often the earliest signs of malignancy.

Full-field digital mammography (FFDM) represented a significant advancement over screen-film mammography by replacing the X-ray film with solid-state detectors. These detectors convert X-rays into electrical signals, which are then translated into digital images. This transition offers superior contrast resolution, particularly in the dense periphery of the breast, and facilitates image storage, retrieval, and transmission via Picture Archiving and Communication Systems (PACS). A further refinement, digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), acquires multiple low-dose images from different angles across a limited arc. These projections are then reconstructed into a series of thin-slice, high-resolution images. This "3D mammography" technique mitigates the issue of tissue superposition, which is a primary limitation of 2D FFDM, by allowing radiologists to scroll through the breast tissue one layer at a time.

Established Strengths of Mammography

The preeminent strength of mammography is its proven role in reducing breast cancer mortality. Large-scale, organized service screening programs have consistently demonstrated a significant reduction in breast carcinoma mortality, a benefit that has been robustly confirmed through decades of data [1].

Mammography excels in the detection of specific malignant features, most notably microcalcifications. These tiny calcium deposits, which can be an early sign of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), are often exquisitely visualized on mammography, sometimes remaining occult on other imaging modalities like ultrasound. The standardization of the BI-RADS (Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System) lexicon, built around mammographic findings, has provided a unified framework for reporting, auditing, and guiding patient management, thereby enhancing the consistency and quality of breast care globally.

Table 1: Key Strengths of Mammography as a Screening Tool

| Strength | Description | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Mortality Reduction | Proven to reduce breast cancer mortality in large randomized controlled trials. | Organized service screening substantially reduces breast carcinoma mortality [1]. |

| Microcalcification Detection | High sensitivity for detecting suspicious microcalcifications, an early sign of cancer. | Critical for diagnosing DCIS; a capability where mammography often outperforms other modalities. |

| Standardized Framework | Use of the BI-RADS system ensures consistent reporting and management recommendations. | Provides a universal language for radiologists, surgeons, and oncologists. |

| Extensive Evidence Base | Decades of longitudinal data and technological refinements (e.g., DBT). | DBT improves performance over DM alone due to enhanced tissue differentiation [2]. |

Inherent Limitations and the Challenge of Dense Breasts

Despite its established role, the diagnostic performance of mammography is not uniform across all patient populations. Its most significant limitation is the degradation of sensitivity in women with dense breast tissue. Radiographically dense breasts have a higher proportion of fibroglandular tissue, which, like many cancers, appears white on a mammogram. This effect, known as the "masking" effect, can obscure underlying malignancies, reducing the sensitivity of mammography from over 85% in fatty breasts to as low as 50% in extremely dense breasts [3]. As breast density is also an independent risk factor for developing breast cancer—with women in the highest density categories having a 4 to 6 times higher risk compared to those with fatty breasts—this limitation affects a population at elevated risk [4].

Other inherent limitations include the use of ionizing radiation, albeit at low doses, and patient discomfort due to the necessary breast compression during the examination. Furthermore, the quest for high sensitivity can sometimes come at the cost of lower specificity, leading to false-positive results. These false positives necessitate additional imaging, ultrasound, or biopsy, contributing to increased healthcare costs, resource utilization, and patient anxiety.

Comparative Performance Data: Mammography vs. Emerging Modalities

Recent high-quality studies have directly compared the diagnostic efficacy of mammography against newer supplemental and standalone modalities, providing quantitative data for objective comparison. A large 2025 randomized controlled trial published in The Lancet compared abbreviated MRI (AB-MRI), ABUS, and contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) in women with dense breasts and a negative mammogram. The findings were revealing: the cancer detection rate for ABUS was 4.2 per 1,000 examinations, significantly lower than the 17.4 for AB-MRI and 19.2 for CEM. For invasive cancers, the rate was 4.2 for ABUS versus 15.0 for AB-MRI and 15.7 for CEM [5]. The study concluded that "contrast-enhanced techniques such as abbreviated MRI and contrast-enhanced mammography have a superior performance compared with whole breast ultrasound" [5].

Another 2025 retrospective study offered a comprehensive comparison of four modalities within the same patient cohort. It confirmed the superior diagnostic performance of Breast MRI, which showed the highest sensitivity (95.1%), specificity (78.7%), and overall accuracy (87.2%). In contrast, DM demonstrated a sensitivity of 87.7% and a notably low specificity of 49.3%. Crucially, this study highlighted that while the combination of DM, DBT, and US achieved a high sensitivity of 96.3%, its specificity plummeted to 32%, illustrating a critical sensitivity-specificity trade-off in multimodal screening [2].

Table 2: Comparative Diagnostic Performance of Breast Imaging Modalities

| Modality | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Overall Accuracy (%) | Key Strength / Weakness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Mammography (DM) | 87.7 [2] | 49.3 [2] | - | Lower sensitivity in dense breasts; low specificity. |

| DM + DBT + US | 96.3 [2] | 32.0 [2] | - | High sensitivity but very low specificity (overdiagnosis risk). |

| ABUS alone | 80.43 [1] | 27.78 [1] | 71.82 [1] | Low specificity; valuable as a complement to DM. |

| Contrast-Enhanced Mammography (CEM) | 93.48 [1] | 11.11 [1] | 80.00 [1] | High cancer detection rate [5]. |

| Breast MRI | 95.1 [2] | 78.7 [2] | 87.2 [2] | Highest overall accuracy; constrained by cost & logistics. |

The Role of Automated Breast Ultrasound (ABUS) in the Screening Paradigm

ABUS was developed to address key limitations of handheld ultrasound (HHUS), namely operator-dependence and non-reproducibility, while leveraging the benefits of sonography in dense tissue [4] [3]. As a supplementary screening tool for women with dense breasts, ABUS increases the cancer detection rate beyond what is achievable with mammography alone. The SomoInsight study, a large multicenter trial, found that adding ABUS to FFDM increased the detection rate by 1.9 per 1000 women, boosting sensitivity by 26.7% [4].

The strengths of ABUS include its standardized acquisition by technologists, multiplanar reconstruction capabilities (particularly the diagnostic "surgical" coronal plane), and the absence of ionizing radiation. However, its disadvantages are notable and include a high false-positive rate, leading to a higher recall rate and lower specificity compared to mammography and MRI [1] [4]. It is also unable to assess the axilla or provide functional data on vascularization and elasticity. From a health economics perspective, a 2025 cost-effectiveness analysis concluded that adding ABUS to mammographic imaging is a cost-effective screening strategy for women with increased breast density or elevated risk [6].

Experimental Protocols and Research Workflows

To contextualize the data presented in this review, understanding the methodologies of key cited studies is crucial for researchers.

- The Lancet RCT Protocol (2025) [5]: This randomized controlled trial recruited women aged 50-70 with dense breasts and a negative mammogram. Participants were independently allocated to receive AB-MRI, ABUS, or CEM. The primary outcome was the cancer detection rate, confirmed by histopathology. The analysis was performed on a per-examination basis, and detection rates were compared for statistical significance.

- Single-Centre Comparative Analysis Protocol (2025) [1]: This study involved patients with focal breast lesions who underwent ABUS, FFDM, and CEM. A total of 169 lesions were identified, with 110 verified by histopathology. The diagnostic performance of each modality was assessed by calculating sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy against the histological gold standard. Statistical correlation between lesion margins and histopathology was also evaluated.

- Multimodal Deep Learning Workflow (2025) [7]: Reflecting a frontier in screening research, this study developed a deep learning-based model using both mammography and ultrasound images. The workflow involved: 1) Data Pre-processing: Localizing and cropping tumor regions in US images using YOLOv8 and grayscale normalization; 2) Data Augmentation: Applying random flipping and elastic deformation to increase dataset size and diversity; 3) Model Construction: Using a late-fusion strategy to train separate deep learning models on DM and US images, with the extracted features fused and connected to a classifier for the final diagnosis.

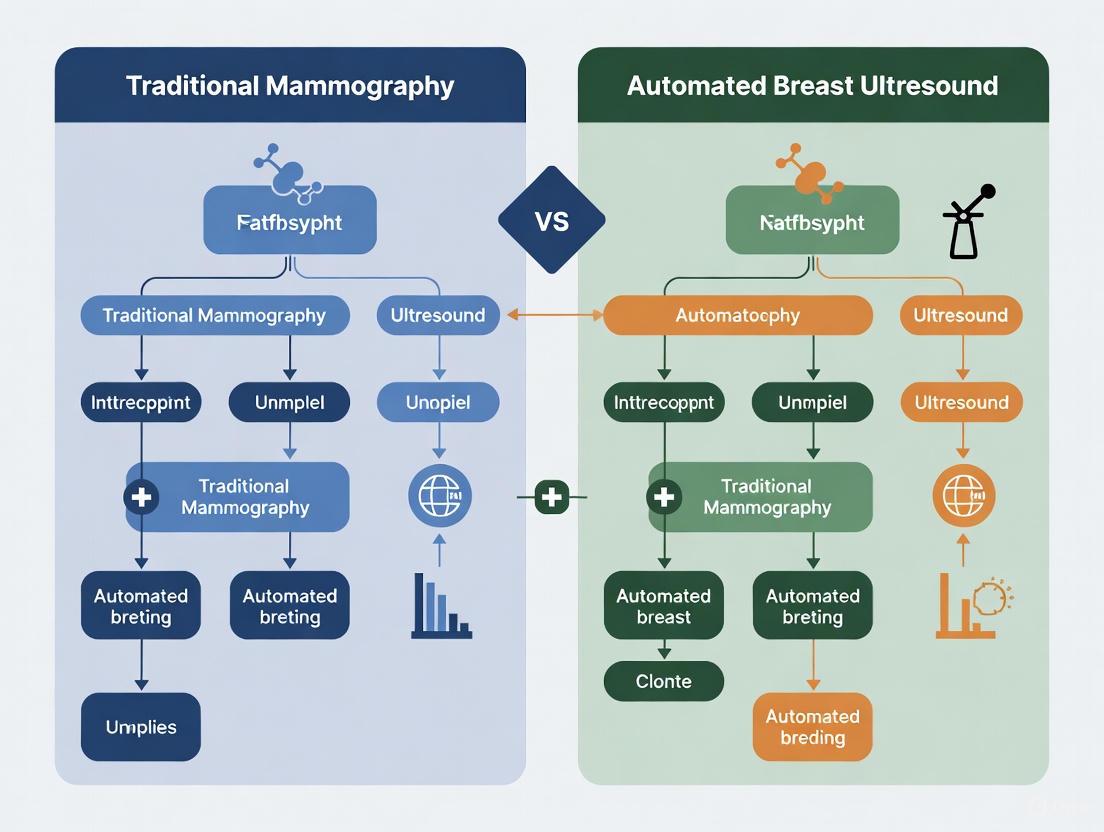

The diagram below illustrates a generalized diagnostic workflow for evaluating breast lesions, integrating multiple imaging modalities and outcome pathways.

Diagram 1: Integrated Diagnostic Workflow for Breast Lesion Evaluation. This flowchart outlines a potential clinical pathway integrating mammography, ABUS, and MRI for comprehensive diagnosis, highlighting decision points based on breast density and risk factors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

For researchers conducting experimental studies in breast imaging comparison, the following tools and methodologies are essential.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Breast Imaging Comparison Studies

| Research Tool / Solution | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| Full-Field Digital Mammography (FFDM) System | Provides the 2D digital baseline images for comparison; the standard against which new modalities are often evaluated. |

| Digital Breast Tomosynthesis (DBT) System | Generates 3D tomosynthesis slices for analysis, used to study the reduction of tissue superposition artifacts. |

| Automated Breast Ultrasound (ABUS) Scanner | Acquires standardized, reproducible 3D volumetric ultrasound data for quantitative analysis and comparison with mammography. |

| Contrast-Enhanced Mammography (CEM) or MRI | Serves as a higher-sensitivity comparator in studies, providing a reference for evaluating the performance of ABUS and standard MG. |

| Histopathology Database | The definitive gold standard for confirming malignancy; essential for calculating sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of imaging tests. |

| Radiomics Software Platforms | Enables high-throughput extraction of quantitative features (shape, texture) from MG, ABUS, and MRI images for AI model development. |

| Deep Learning Frameworks (e.g., CNN models) | Used to develop and train multimodal classification models that fuse data from MG and US/ABUS to improve diagnostic performance [7]. |

Mammography remains the foundational pillar of breast cancer screening, with an unparalleled evidence base supporting its role in reducing mortality. Its strengths in detecting microcalcifications and its standardized implementation are undeniable. However, its inherent limitation in women with dense breasts—a population at elevated risk—is a significant challenge that the field must address. Contemporary research clearly demonstrates that while supplemental screening with ABUS effectively increases cancer detection rates and is a cost-effective strategy, its performance in terms of cancer detection yield and specificity is surpassed by contrast-enhanced techniques like MRI and CEM. The future of breast imaging research lies not in supplanting mammography, but in optimizing its integration with other modalities. The development of AI-based multimodal models that synergistically combine data from mammography, ABUS, and other imaging sources represents a promising frontier for enhancing diagnostic accuracy, personalizing screening approaches, and ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Breast cancer remains a pervasive global health challenge, with early detection being a cornerstone of reducing mortality. Mammography (MG) has long been the primary screening method, credited with a significant reduction in breast cancer deaths [8]. However, its effectiveness is substantially compromised in women with dense breast tissue—a condition present in approximately 40% of the screening population [9] [10]. This "density dilemma" creates a dual problem: dense breast tissue can mask underlying tumors on a mammogram due to a summation phenomenon where both tumors and glandular tissue appear white, and it is also an independent risk factor for developing breast cancer [8] [10]. The sensitivity of mammography can plummet from over 88% in fatty breasts to as low as 62% in extremely dense breasts, leaving many cancers undetected [10]. It is within this clinical gap that Automated Breast Ultrasound (ABUS) has emerged as a critical adjunctive imaging modality. ABUS offers a standardized, reproducible ultrasound-based approach designed to enhance cancer detection in dense breasts without the operator-dependency that characterizes traditional Handheld Ultrasound (HHUS). This guide provides a objective comparison of the diagnostic performance of ABUS against MG and other alternatives, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies for the research community.

Performance Comparison: ABUS vs. Established Modalities

Extensive clinical studies have systematically evaluated the diagnostic performance of ABUS against mammography and handheld ultrasound. The data, summarized in the table below, reveals a nuanced landscape of complementary strengths.

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance of ABUS vs. Mammography and Handheld Ultrasound

| Modality | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Key Study Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABUS | 92.8 [11] | 93.0 [11] | 0.96 [12] | In women 40-69, ABUS had significantly higher sensitivity (93.5%) than MG (87.9%) [11]. |

| Mammography (MG) | 87.9 [11] | 91.6 [11] | - | MG sensitivity drops significantly in dense breasts; specificity is comparable to ABUS [11]. |

| Handheld Ultrasound (HHUS) | 96.3 [11] | 89.6 [11] | - | HHUS has higher sensitivity but lower specificity compared to ABUS [11]. |

| Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) | 88 [12] | 76 [12] | 0.89 [12] | ABUS shows higher specificity and Diagnostic Odds Ratio (89 vs. 24) than CEUS [12]. |

Comparative Analysis with Other Modalities

ABUS vs. Contrast-Enhanced Mammography (CEM): A 2025 single-center study provided a direct comparison. It found that while CEM detected 88 lesions and ABUS detected 106 out of a total of 169, ABUS showed the highest compliance with histopathology for determining lesion size (p=0.258). The sensitivity and accuracy of the combination of FFDM and ABUS were 100% and 84.55%, respectively, outperforming the FFDM+CEM combination [13].

ABUS in a Multimodal Context: The superior post-test probability of ABUS (75%) compared to CEUS (48%) underscores its utility in confirming a diagnosis [12]. Furthermore, the integration of ABUS with mammography in dense breasts has been shown to find 35.7% more cancers than mammography alone, establishing its vital role as an adjunctive screening tool [10].

Insights from Key Experimental Studies

Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study in China

A large-scale study provides robust, head-to-head data on ABUS, HHUS, and MG.

Experimental Protocol: This multicenter study recruited 1,922 symptomatic women aged 30-69 across five tertiary hospitals in China [11]. Women aged 30-39 underwent ABUS and HHUS, while women aged 40-69 underwent ABUS, HHUS, and MG [11]. All images were interpreted using the BI-RADS lexicon, and all BI-RADS 4 and 5 lesions were confirmed pathologically, establishing a definitive gold standard [11]. The primary outcomes were the sensitivity and specificity of each modality, compared using appropriate statistical tests [11].

Key Outcomes: The study demonstrated that ABUS had a significantly higher specificity than HHUS (93.0% vs. 89.6%, p<0.01) while HHUS had a marginally higher sensitivity (96.3% vs. 92.8%, p=0.01) [11]. Crucially, in the older cohort, ABUS showed significantly higher sensitivity than mammography (93.5% vs. 87.9%) with comparable specificity, affirming its value in breast cancer diagnosis [11].

The TDSC-ABUS2023 Challenge

This recent challenge highlights the evolving role of artificial intelligence in enhancing ABUS.

Experimental Protocol: The TDSC-ABUS2023 challenge was organized to advance algorithmic research for tumor detection, segmentation, and classification in 3D ABUS images [14]. The initiative created a benchmark dataset to address the significant variability in tumor size and shape, unclear boundaries, and low signal-to-noise ratio that complicate ABUS image analysis [14]. Participants developed and submitted algorithms to perform these tasks on a well-labeled ABUS dataset, with performance evaluated against ground-truth annotations [14].

Key Outcomes: The challenge successfully established a public benchmark for ABUS image analysis and summarized top-performing algorithms [14]. It serves as an open-access platform to inspire and measure future developments in computer-aided diagnosis systems for ABUS, which can further reduce interpretation time and improve diagnostic consistency [14].

The Research Toolkit for ABUS Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ABUS Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| ABUS Imaging System | Acquires full breast volume scans automatically. | Systems like GE Healthcare's Invenia ABUS use a 6–14 MHz transducer for image acquisition [8]. |

| Ultrasound Coupling Gel | Ensures acoustic contact between transducer and skin. | Must be hypoallergenic and applied evenly to eliminate air gaps [8]. |

| Sponge Wedge | Positions the patient to evenly distribute breast tissue. | Placed under the patient's arm while supine for standardized scanning [8]. |

| BI-RADS Atlas | Standardized lexicon for reporting and classifying findings. | Essential for consistent image interpretation and study comparison [11]. |

| Histopathology Setup | Provides the gold standard for diagnostic confirmation. | Includes core needle biopsy (CNB), tissue processing, and H&E staining [13]. |

| Workstation with 3D MPR | Enables review and multi-planar reconstruction of volume data. | Allows radiologists to scroll through coronal, sagittal, and axial planes [15]. |

Workflow and Conceptual Framework

The integration of ABUS into clinical practice and research follows a structured workflow, while its primary value is conceptualized in addressing the limitations of mammography.

Diagram 1: ABUS research workflow.

Diagram 2: ABUS addresses the density dilemma.

The evidence demonstrates that ABUS has firmly established itself as a pivotal technology in the landscape of breast imaging, primarily by effectively addressing the significant diagnostic challenge posed by dense breast tissue. While mammography remains the foundational screening tool, ABUS provides a vital adjunct that significantly increases cancer detection rates with higher sensitivity and comparable or superior specificity to other modalities. Its standardized, reproducible nature mitigates the operator-dependency of HHUS, making it suitable for broader screening applications. For researchers and clinicians, the data indicates that the future of breast cancer detection lies not in a single monolithic technology, but in an integrated, intelligent approach. ABUS is a key component of this approach, contributing to a personalized, multi-modal strategy that promises to improve early detection and, ultimately, patient outcomes for the large population of women with dense breasts.

Breast density, defined as the proportion of fibroglandular tissue relative to fatty tissue visible on a mammogram, presents a significant dual challenge in breast cancer care. First, dense breast tissue is an independent risk factor for developing breast cancer. Second, it can mask tumors during standard mammographic screening, leading to decreased sensitivity and potential false-negative results [16]. This combination of increased risk and reduced detection capability creates a critical problem in oncology and diagnostic imaging. The recognition of breast density as a major factor influencing screening outcomes has catalyzed research into complementary imaging technologies, such as Automated Breast Ultrasound (ABUS), to improve early cancer detection in this population. Understanding the prevalence, risk implications, and technical challenges associated with breast density is fundamental to advancing breast cancer detection strategies and developing more personalized screening protocols for at-risk women.

Breast Density Prevalence and Risk Correlation

Classification and Prevalence

Breast density is clinically classified using the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data Systems (BI-RADS) into four categories: (A) almost entirely fatty, (B) scattered areas of fibroglandular density, (C) heterogeneously dense, and (D) extremely dense. Breasts categorized as C and D are considered "dense breasts" [16]. The prevalence of dense breasts varies significantly across populations and demographic factors. Approximately 43% of women aged 40-74 have heterogeneously or extremely dense breasts (types C and D) [16]. Prevalence demonstrates a strong inverse relationship with age, decreasing from 56.6% in women aged 40-44 years to 28.4% in women aged 85 and older [16].

Significant racial and ethnic variations in breast density prevalence have been documented. A large study of 2,667,207 mammography examinations found that dense breasts are most prevalent among Asian women (66.0%), followed by non-Hispanic White (45.5%), Hispanic/Latina (45.3%), and non-Hispanic Black (37.0%) women [17]. These differences persist even after adjusting for age, menopausal status, and body mass index (BMI), with Asian women maintaining a 19% higher prevalence and Black women an 8% higher prevalence of dense breasts compared to the overall population [17].

Table 1: Breast Density Prevalence Across Demographic Groups

| Demographic Factor | Category | Prevalence of Dense Breasts | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (Age 40-74) | - | 43% | Heterogeneously or extremely dense (BI-RADS C & D) [16] |

| By Age | 40-44 years | 56.6% | Decreases with advancing age [16] |

| 85+ years | 28.4% | [16] | |

| By Race/Ethnicity | Asian | 66.0% | Highest prevalence [17] |

| Non-Hispanic White | 45.5% | Slightly below average [17] | |

| Hispanic/Latina | 45.3% | Similar to White population [17] | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 37.0% | Lowest prevalence [17] |

Mammographic Density and Cancer Risk

Mammographic density is a well-established independent risk factor for breast cancer, associated with a 1- to 6-fold increase in incidence [16]. A 2022 meta-analysis of nine observational studies determined that individuals with extremely dense breast tissue (BI-RADS D) had a 2.11-fold (95% CI 1.84-2.42) higher risk of developing breast cancer compared to those with scattered dense breast tissue (BI-RADS B) [16]. This risk association persists for extended periods, with studies demonstrating that the magnitude of association between percent density and breast cancer remains similar when the time since the mammogram is <2, 2 to <5, and 5 to <10 years [18].

The increased cancer risk associated with breast density has become sufficiently significant that it has been incorporated into epidemiologically based cancer risk calculation models, such as the Tyrer-Cuzick model (version 8), since 2022 [16]. This inclusion has enhanced the accuracy of risk stratification for both high-risk (>8% 10-year risk) and low-risk (<2% 10-year risk) women [16]. The biological mechanisms underlying this increased risk are thought to involve both mammographic masking (where dense tissue obscures tumors) and specific histopathological features associated with dense tissue, including increased stromal volume, epithelial content, and reduced lobular involution [16].

Impact on Conventional Mammography Performance

The Masking Effect and Sensitivity Reduction

The presence of dense breast tissue significantly impairs the performance of conventional mammography through a "masking effect," where the radiologically dense (white) fibroglandular tissue obscures tumors, which also appear white on mammograms [16] [8]. This phenomenon substantially reduces mammographic sensitivity, creating a critical diagnostic challenge. The sensitivity of full-field digital mammography (FFDM) decreases dramatically with increasing breast density—from approximately 98% for entirely fatty breasts (BI-RADS A) to just 48% for extremely dense breasts (BI-RADS D) [8]. This reduction in sensitivity leads to higher rates of interval cancers (cancers diagnosed between routine screenings) and delayed diagnoses in women with dense breasts [16] [19].

The masking effect occurs because mammography produces summation images where structures in the same plane overlap. In dense breasts, glandular and stromal tissues are poorly distinguishable, causing overlapping of structures that can obscure tumors [8]. Additionally, denser breasts are often more difficult to compress adequately during mammography, further exacerbating the tissue overlap issue and reducing image quality [8]. This technical limitation of conventional mammography has driven the development and evaluation of supplemental screening modalities for women with dense breasts.

Table 2: Impact of Breast Density on Mammography Performance

| BI-RADS Density Category | Breast Composition | Mammography Sensitivity | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (Almost entirely fatty) | ≤25% fibroglandular tissue | ~98% [8] | Minimal masking effect |

| B (Scattered fibroglandular densities) | 25%-50% fibroglandular tissue | High | Limited masking effect |

| C (Heterogeneously dense) | 50%-75% fibroglandular tissue | Significantly reduced | Moderate masking effect, increased cancer risk [16] |

| D (Extremely dense) | ≥75% fibroglandular tissue | ~48% [8] | Severe masking effect, 2.11x higher cancer risk vs. category B [16] |

Automated Breast Ultrasound (ABUS) as a Complementary Modality

Technology and Workflow

Automated Breast Ultrasound (ABUS) is an advanced ultrasound technology developed to address the limitations of both mammography and handheld ultrasound (HHUS) in evaluating dense breasts. Approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2012 as a supplemental screening tool for women with dense breasts, ABUS uses an automated transducer to systematically acquire volumetric images of the entire breast [20] [4]. Unlike HHUS, which is operator-dependent and provides limited field-of-view images, ABUS standardizes the image acquisition process, separating acquisition from interpretation and providing comprehensive, reproducible datasets [20] [4].

The ABUS examination typically involves imaging each breast in three standard views (anterior-posterior, medial, and lateral) using a high-frequency linear transducer (typically 6-14 MHz) [4] [8]. For women with larger breasts (cup size D or larger), additional views may be necessary to ensure complete coverage [4]. During acquisition, the transducer moves automatically across the breast in overlapping linear rows, generating volumetric data that is reconstructed into three orthogonal planes: axial, sagittal, and coronal [20]. The coronal plane, unique to ABUS, provides a "surgical view" of the breast that often reveals the "retraction phenomenon" characteristic of malignant lesions—appearing as hyperechoic straight lines radiating from the mass surface [4].

Comparative Performance Data

Multiple studies have demonstrated that ABUS significantly improves cancer detection rates when used as an adjunct to mammography in women with dense breasts. The SomoInsight study, one of the largest screening trials evaluating ABUS, included 15,318 asymptomatic women with dense breasts and found that adding ABUS to FFDM increased the cancer detection rate by 1.9 per 1000 women screened, representing a 26.7% increase in sensitivity [4]. Other studies have reported even greater improvements, with cancer detection rates increasing by 2.4 to 7.7 per 1000 women screened when ABUS was combined with FFDM compared to FFDM alone [4].

A 2025 comparative analysis of ABUS and contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) found that while CEM demonstrated higher sensitivity (93.48% vs. 80.43%) and accuracy (80% vs. 71.82%) than ABUS, the combination of FFDM and ABUS achieved 100% sensitivity with an AUC of 0.947 [1]. The same study reported that ABUS showed the highest correlation with histopathology in determining lesion size (p=0.258) and detected 36 additional lesions not visible on other imaging examinations [1].

Recent data from the BRAID study, a large prospective trial published in 2025, provides direct comparison of multiple supplemental screening modalities. This study of over 9,000 women with dense breasts and negative mammograms found that ABUS detected 4.2 cancer cases per 1000 examinations, compared to 17.4 for abbreviated MRI (AB-MRI) and 19.2 for CEM [19]. While AB-MRI and CEM demonstrated superior detection rates, ABUS had a lower recall rate (4%) compared to both AB-MRI (9.7%) and CEM (9.7%) [19].

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Imaging Modalities in Dense Breasts

| Imaging Modality | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Cancer Detection Rate (per 1000 exams) | Recall Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFDM alone | 40-76 [4] | 85.4-99.7 [4] | Baseline | 150.2/1000 [4] |

| FFDM + ABUS | 81-100 [1] [4] | 72-98.7 [1] [4] | +1.9 to +7.7 over FFDM alone [4] | 284.9/1000 [4] |

| Abbreviated MRI | - | - | 17.4 [19] | 9.7 [19] |

| Contrast-Enhanced Mammography | 93.48 [1] | 11.11 [1] | 19.2 [19] | 9.7 [19] |

Research Reagent Solutions for Breast Density and ABUS Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Breast Density and ABUS Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| ABUS Imaging Systems | Volumetric breast image acquisition | Invenia ABUS (GE Healthcare); ACUSON S2000 ABVS (Siemens) [20] |

| High-Frequency Transducers | Tissue penetration and resolution | 6-14 MHz linear transducers optimized for automated scanning [8] |

| BI-RADS Reference Standards | Standardized density classification and reporting | BI-RADS 5th edition density categories (A-D) [16] |

| Image Analysis Software | Quantitative density measurement and feature extraction | Computerized texture analysis, convolutional neural networks (CNN) for automated classification [20] [16] |

| Radiomics Analysis Platforms | High-dimensional feature extraction from images | Texture, shape, and wavelet feature analysis; machine learning model development [20] |

| Histopathological Validation Tools | Correlation of imaging findings with tissue pathology | Immunohistochemistry markers, tissue staining for fibrosis and lobular involution [16] |

Experimental Protocols for ABUS Performance Evaluation

Comparative Diagnostic Performance Study

A 2025 single-center study provides a robust methodological framework for comparing ABUS with other complementary breast imaging modalities [1]. The study enrolled 81 patients with focal breast lesions who underwent ABUS, FFDM, and contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM), with 169 focal lesions identified and 110 lesions histopathologically verified (92 malignant, 5 B3 lesions, 13 benign) [1].

Key Methodology:

- Patient Selection: Consecutive patients with focal breast lesions identified through screening or diagnostic workup

- Imaging Protocol: All participants underwent ABUS, FFDM, and CEM examinations

- Reference Standard: Histopathological verification through biopsy or surgical resection

- Image Analysis: Qualitative assessment of lesion characteristics (margin, size) and quantitative analysis of detection rates

- Statistical Analysis: Calculation of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy for each modality, with comparison of area under the curve (AUC) for combined approaches [1]

This study demonstrated that while CEM showed superior individual performance metrics, the combination of FFDM and ABUS achieved the highest sensitivity (100%) with excellent accuracy (AUC=0.947) [1].

Artificial Intelligence and Radiomics Analysis

Emerging research methodologies incorporate artificial intelligence (AI) and radiomics to enhance ABUS performance. The standard workflow for AI-based ABUS radiomics analysis involves multiple systematic stages [20]:

Protocol Steps:

- Image Acquisition and Pre-processing: Standardized ABUS volume acquisition with noise reduction and resolution enhancement

- Tumor Segmentation: Manual, semi-automatic, or automatic delineation of regions of interest (ROIs)

- Feature Extraction: High-throughput extraction of quantitative features including shape, texture, and wavelet features

- Feature Selection: Dimensionality reduction using filter, wrapper, or embedded methods to identify most predictive features

- Model Building and Validation: Development of machine learning or deep learning classifiers with cross-validation and external validation [20]

This methodology enables the extraction of subvisual imaging biomarkers that can improve diagnostic accuracy and risk stratification beyond conventional image interpretation.

The challenge of breast density significantly impacts both cancer risk and detection capability, necessitating advanced imaging approaches beyond conventional mammography. ABUS has emerged as a valuable standardized supplemental modality that improves cancer detection rates in women with dense breasts, particularly when combined with mammography. Current evidence supports its role in providing reproducible, comprehensive evaluation of breast tissue, with the unique coronal plane offering additional diagnostic information. However, recent comparative studies indicate that while ABUS provides definite improvements over mammography alone, alternative supplemental modalities like abbreviated MRI and contrast-enhanced mammography may offer higher detection rates, though with different trade-offs in accessibility, cost, and recall rates. Future research directions should focus on optimizing patient selection criteria for different supplemental screening modalities, further developing AI and radiomics approaches to enhance ABUS performance, and establishing cost-effective integrated screening protocols for women with dense breasts.

Breast cancer remains a paramount public health challenge, being the most frequent malignant tumor diagnosed in women worldwide [21]. The evolution of breast imaging technologies has been fundamentally driven by a critical limitation of the foundational screening tool: the reduced sensitivity of conventional 2D mammography in radiographically dense breasts, where overlapping tissue can mask cancers [22]. This technological trajectory has progressed from two-dimensional projections to advanced three-dimensional modalities that minimize tissue superposition, namely Digital Breast Tomosynthesis (DBT) and volumetric ultrasound, including Automated Breast Ultrasound (ABUS). DBT, often termed 3D mammography, utilizes a moving X-ray tube to acquire multiple low-dose images across an arc, which are reconstructed into thin slices of the breast [23]. ABUS, on the other hand, employs automated transducers to generate a three-dimensional volume dataset of the entire breast using ultrasound, providing a completely different contrast mechanism based on acoustical properties [24]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of the diagnostic performance, technical protocols, and clinical applications of 2D mammography, DBT, and ABUS, with a specific focus on their role in evaluating breast masses within the context of dense breast tissue.

Technical Principles and Imaging Protocols

2D Digital Mammography (FFDM)

Full-Field Digital Mammography (FFDM) produces a single, two-dimensional image of the compressed breast from two standard views: craniocaudal (CC) and mediolateral oblique (MLO) [23]. Each pixel in the image represents the summation of X-ray attenuation through the entire thickness of the breast. This tissue superposition is the primary cause of both false positives, where normal overlapping tissue simulates a lesion, and false negatives, where cancers are obscured by dense parenchyma [25] [22]. The radiation dose per view for FFDM typically ranges between 150-250 millirads [22].

Digital Breast Tomosynthesis (DBT)

DBT addresses the limitation of tissue superposition by acquiring a series of low-dose projection images as the X-ray tube moves through a limited arc (typically 11-60 degrees) over a few seconds [22] [23]. The number of projections varies by manufacturer, typically from 9 to 25 exposures [22]. These projection images are then reconstructed using algorithms (e.g., filtered back projection, iterative reconstruction) into a stack of thin, high-resolution slices, usually 1 mm thick, for radiologist review [22] [23]. This allows the radiologist to scroll through the breast tissue in thin sections, effectively "unmasking" lesions hidden by overlapping tissue.

- Radiation Dose: The radiation dose for a DBT exam is a key consideration. When DBT is combined with a standard 2D mammogram (combo-mode), the total dose is higher than FFDM alone. However, the development of synthesized 2D images (C-View), generated from the DBT dataset, allows for a radiation dose that is only about 19% higher on average than FFDM alone, a significant reduction from the combo-mode [23]. Some 1-view DBT protocols can achieve a dose comparable to or even slightly lower than 2D mammography [23].

Automated Breast Ultrasound (ABUS)

ABUS is a three-dimensional volumetric imaging technique designed to overcome the operator-dependence and time-intensive nature of handheld ultrasound (HHUS) for screening [24]. A standard ABUS protocol involves scanning each breast separately in three planes: anterior-posterior (AP), lateral (LAT), and medial (MED), resulting in a minimum of six volume sets [24]. For larger breasts, additional views may be required to ensure complete coverage. The system uses a long, automated transducer that applies uniform compression, and the volume data is automatically processed with multiplanar reconstruction (axial, coronal, and sagittal planes) [24]. The entire examination, including patient preparation, takes approximately 15-20 minutes [24]. ABUS is particularly valuable as a supplemental screening tool following a negative mammogram in women with dense breasts (BI-RADS density C and D) [24].

Table 1: Summary of Key Technical Parameters for Breast Imaging Modalities

| Parameter | 2D FFDM | Digital Breast Tomosynthesis (DBT) | Automated Breast Ultrasound (ABUS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | 2D X-ray projection | Quasi-3D reconstruction from limited-angle X-ray projections | 3D volumetric imaging using ultrasound |

| Standard Views | CC, MLO (2 per breast) | CC, MLO (2 per breast) | AP, LAT, MED (≥3 per breast) |

| Image Output | 2 flat images per view | ~60-120 thin slices (1 mm) per view | Hundreds of images per volume set |

| Primary Strength | Calcification assessment | Mass detection, characterizing margins, reducing tissue overlap | Detecting mammographically-occult cancers in dense tissue |

| Radiation | Yes (reference dose) | Similar to slightly higher than FFDM; ~19% higher with synthetic 2D | No |

| Exam Duration | ~10 minutes [26] | Similar to FFDM | 15-20 minutes [24] |

Comparative Diagnostic Performance

The transition from 2D to 3D imaging is substantiated by a wealth of data demonstrating improvements in key performance metrics, including cancer detection rates, recall rates, and diagnostic accuracy.

Cancer Detection and Recall Rates

A large meta-analysis comparing DBT plus synthetic 2D mammography to 2D mammography alone demonstrated a statistically significant increase in the cancer detection rate (CDR) from 4.68 to 7.40 per 1000 women screened [23]. The same analysis showed that the recall rate (the proportion of women called back for additional imaging) dropped dramatically from 78.8 to 42.3 per 1000 screened with the combined DBT and synthetic 2D approach [23]. This combination of higher CDR and lower recall rate represents a major advancement in screening efficiency.

For ABUS used as a supplemental screening tool in women with dense breasts, the incremental cancer detection rate compared to mammography alone ranges from 1.9 to 7.7 cases per 1000 women [24]. The cancers detected by supplemental ABUS are often small, invasive, and node-negative, indicating a benefit for early detection [24]. A direct, prospective comparison study of DBT and ABUS in characterizing breast masses found their sensitivity to be equivalent (100% for both), while DBT showed a marginally higher specificity (81.25% for DBT vs. 75% for ABUS) [27].

Characterization of Breast Masses

The ability to characterize a detected mass—distinguishing benign from malignant features—is critical for avoiding unnecessary biopsies. DBT excels in this domain by providing superior visualization of mass margins and architecture. It allows radiologists to better assess spiculations and the true extent of a lesion, which are crucial indicators of malignancy [21]. Similarly, ABUS provides detailed information on mass shape, margins, and echogenicity. A study comparing the two modalities found high agreement in assessing the shape and location of masses, though DBT was more sensitive in detecting associated calcifications [27]. The study also noted that DBT was superior to ABUS in demonstrating the extension of a lesion beyond the mass margin [27].

Table 2: Comparison of Diagnostic Performance Metrics in Screening

| Metric | 2D FFDM | DBT (+ Synthetic 2D) | ABUS (Supplemental) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Detection Rate (per 1000) | 4.68 [23] | 7.40 [23] | Incremental 1.9 - 7.7 [24] |

| Recall Rate (per 1000) | 78.8 [23] | 42.3 [23] | Increases vs. mammography alone [24] |

| Sensitivity (Mass Characterization) | Benchmark | 100% [27] | 100% [27] |

| Specificity (Mass Characterization) | Benchmark | 81.25% [27] | 75% [27] |

| Strength in Dense Breasts | Low sensitivity, high masking | Improved over 2D | High for mammographically-occult cancers |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

For researchers designing studies to evaluate these technologies, understanding the standardized protocols and methodologies used in pivotal clinical trials is essential.

Digital Breast Tomosynthesis Characterization Study

A prospective study comparing DBT and ABUS for mass characterization provides a robust experimental model [27].

- Patient Cohort: 32 women with 37 breast masses (16 benign, 21 malignant) detected via clinical or mammographic exam.

- Image Acquisition: All patients underwent both DBT and ABUS examinations. DBT was performed using a GE prototype system, acquiring CC and MLO views with breast compression similar to mammography. ABUS was performed using a GE Invenia ABUS system, with a layer of lotion applied and a curved transducer panel used to flatten the tissue against the body [27].

- Image Analysis: Images from both modalities were analyzed in consensus by two experienced radiologists blinded to pathological data. Each mass was evaluated for shape, margin, asymmetry, calcifications, number, location, extension, skin thickening, and final BI-RADS classification [27].

- Reference Standard: Pathological results (for 32 masses) and imaging follow-up for typically benign findings (5 masses) served as the gold standard [27].

- Statistical Analysis: Data were analyzed using SPSS. Standard diagnostic indices (sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV) were calculated, and categorical data were compared using the Chi-square test [27].

Automated Breast Ultrasound (ABUS) with CAD

A multiple-reader, multiple-case study evaluated the impact of Computer-Aided Detection (CAD) on ABUS performance [28].

- Sample Selection: 120 unilateral ABUS examinations were randomly selected from a multi-institutional archive, comprising 30 malignant (20 of which were mammography-occult), 30 benign, and 60 normal cases. All cases had histopathological verification or ≥2 years of negative follow-up [28].

- Reading Protocol: Eight radiologists read each case twice: once with CAD (CAD-ABUS) and once without (ABUS), with a washout period of over 8 weeks between sessions. For each case, readers provided a BI-RADS score and a level of suspiciousness (0-100) [28].

- Outcome Measures: The primary outcomes were reading time (RT), sensitivity, specificity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV), and the area under the curve (AUC). These metrics were compared between the CAD-ABUS and ABUS reading sessions [28].

- Key Finding: The use of CAD for ABUS significantly reduced the average reading time per case (133.4 seconds with CAD vs. 158.3 seconds without) without compromising sensitivity or specificity, demonstrating its potential to improve workflow efficiency [28].

Visualization of Workflows and Applications

The distinct imaging principles of DBT and ABUS lead to different clinical workflows and strengths, which can be visualized in the following diagram.

Diagram 1: Imaging Workflows and Primary Outcomes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers conducting clinical studies or developing algorithms in breast imaging, familiarity with the following key tools and technologies is essential.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Technologies

| Item | Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| DBT System with Synthetic 2D | Enables comparison of DBT performance against 2D without increased radiation dose from combo-mode. | Key for studies on radiation dose optimization [23]. |

| ABUS System with Dedicated Workstation | Provides standardized 3D ultrasound volumes for radiologist interpretation or CAD development. | Volume data cannot be viewed on standard PACS [24]. |

| Computer-Aided Detection (CAD) Software | Object of study for improving reading efficiency and reducing perceptual errors. | Shown to reduce ABUS reading time without loss of accuracy [28]. |

| BI-RADS Atlas (5th Ed. or later) | Standardizes lexicon for describing findings, density, and final assessment categories across studies. | Critical for ensuring consistent data collection and reporting [21]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software (e.g., SPSS) | For analysis of diagnostic performance metrics (sensitivity, specificity, AUC) and comparative statistics. | Used in pivotal studies to calculate performance indices [27]. |

| Annotated Image Databases | Serves as a ground-truthed dataset for training and validating machine learning algorithms. | Should include pathology-proven cases with different modalities [28]. |

The technological trajectory from 2D mammography to 3D tomosynthesis and volumetric ultrasound scanning represents a paradigm shift in breast imaging, driven by the need to overcome the fundamental physical limitation of tissue superposition. DBT has firmly established itself as a superior screening tool, increasing cancer detection while reducing false positives, and is increasingly becoming the standard of care. ABUS has carved out a vital role as a reproducible and effective supplemental screening modality, particularly for women with dense breasts where mammography's sensitivity is compromised. The choice of modality is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of understanding their complementary strengths. Future directions point toward the integration of artificial intelligence, further refinement of synthetic 2D imaging to reduce radiation, and the continued use of multi-modal approaches to achieve the ultimate goal of detecting every breast cancer at its earliest, most treatable stage.

Operationalizing Screening: Clinical Workflows and Application Scenarios for ABUS and Mammography

Breast cancer remains a pervasive global health challenge, driving the continuous evolution of imaging technologies for early detection and diagnosis. Mammography has served as the cornerstone of breast cancer screening for decades, while Automated Breast Ultrasound (ABUS) has more recently emerged as a standardized, operator-independent ultrasound technique. Understanding the distinct procedural methodologies of these two imaging modalities is critical for researchers and clinicians aiming to optimize diagnostic pathways. This guide provides a systematic, step-by-step comparison of ABUS and mammography image acquisition processes, supported by experimental data and technical protocols, to elucidate their respective roles in breast imaging research and clinical practice.

The core technologies underpinning mammography and ABUS are fundamentally different, which directly influences their application and diagnostic capabilities.

Mammography: This technique utilizes low-dose ionizing radiation to create two-dimensional or three-dimensional summation images of the compressed breast. The differential absorption of X-rays by various breast tissues (adipose, glandular, pathological) creates the image contrast. Recent advancements include Digital Breast Tomosynthesis (DBT), which acquires images from multiple angles to create thin-slice reconstructions, reducing tissue superposition artifacts [29]. As a screening tool, its primary strength lies in detecting microcalcifications and architectural distortions, though its sensitivity decreases significantly in dense breast tissue [30].

Automated Breast Ultrasound (ABUS): Approved by the FDA in 2012 as a supplemental screening tool, ABUS employs high-frequency sound waves (typically 6–14 MHz) to generate volumetric data of the entire breast [4] [20]. A transducer moves automatically across the breast, emitting ultrasound waves and receiving echoes to construct multiplanar images (axial, sagittal, and coronal). A key technological advantage is the reconstruction of the coronal plane, which provides a unique "surgical view" of the breast parenchyma and can reveal the "retraction phenomenon" often associated with malignant lesions [4]. ABUS was developed to standardize breast ultrasound, eliminating the operator-dependency of handheld ultrasound (HHUS) and enabling comprehensive documentation for comparison across serial exams [8].

Table 1: Core Technological Principles of Mammography and ABUS

| Feature | Mammography | ABUS |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Principle | Ionizing Radiation | High-Frequency Sound Waves |

| Primary Output | 2D or 3D Summation Images | Volumetric, Multiplanar Reconstructions |

| Key Technological Advancements | Full-Field Digital Mammography (FFDM), Digital Breast Tomosynthesis (DBT) | Whole-Breast Volumetric Scanning, Coronal Plane Reconstruction |

| Standard of Practice | Primary screening tool; well-established guidelines | Supplemental screening for dense breasts; evolving guidelines |

Step-by-Step Image Acquisition Protocols

A detailed comparison of the acquisition protocols reveals profound differences in patient positioning, preparation, and the technical execution of the scan, each with distinct implications for patient experience and image quality.

Patient Preparation and Positioning

Mammography Procedure:

- Preparation: Patients are advised to avoid using deodorants, talcum powders, or lotions on their breasts or underarms on the day of the exam, as these can create artifacts mimicking pathology [29].

- Positioning: The examination is performed with the patient standing. Each breast is positioned in turn on a special platform.

- Compression: A clear plastic paddle progressively compresses the breast. This is a critical step to:

- Even out breast thickness to visualize all tissue.

- Spread out tissue to reduce superimposition, preventing small lesions from being hidden.

- Immobilize the breast to prevent motion blur.

- Allow for a lower radiation dose by imaging a thinner tissue volume [29].

- Standard Views: A minimum of two views per breast are acquired: the cranio-caudal (CC), from top to bottom, and the mediolateral-oblique (MLO), from the center to the side at an angle [29]. The entire process typically takes about 30 minutes.

ABUS Procedure:

- Preparation: Unlike mammography, no restrictions on lotions or powders are needed. A hypoallergenic acoustic coupling gel is applied to the breast to ensure proper contact and transmission of sound waves [8].

- Positioning: The patient lies in a supine position. To evenly distribute breast tissue, a sponge wedge may be placed under the patient's arm, with the nipple pointing toward the ceiling [8]. This position is more comfortable and eliminates the need for compression.

- Scanning: The technologist selects the appropriate scan settings based on breast size (cup A-D+). A large, automated transducer then scans the breast in overlapping linear rows.

- Standard Views: Typically, three scans per breast are acquired in the anterior-posterior (AP), medial, and lateral views. For larger breasts (cup D and above), additional superior and inferior views may be necessary to ensure complete coverage [4] [11]. The patient must remain still and breathe quietly during the acquisition, which takes just a few minutes per view.

The workflow diagrams below illustrate the distinct steps involved in each procedure.

Diagram 1: Mammography Image Acquisition Workflow

Diagram 2: ABUS Image Acquisition Workflow

Comparative Diagnostic Performance in Clinical Research

Extensive clinical studies have quantified the performance of ABUS and mammography, both as standalone modalities and in combination. The data consistently highlights the complementary nature of these techniques, particularly in specific patient subgroups.

Sensitivity and Specificity Analysis

A large 2021 multicenter, cross-sectional study in China involving 1,922 women provided robust, head-to-head comparative data. The study evaluated the diagnostic performance of ABUS, handheld ultrasound (HHUS), and mammography in symptomatic women [11].

Table 2: Diagnostic Performance of ABUS, HHUS, and Mammography (Whole Study Population, n=1,922) [11]

| Modality | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| ABUS | 92.8% (375/404) | 93.0% (1411/1518) |

| HHUS | 96.3% (389/404) | 89.6% (1360/1518) |

| Mammography (MG)* | 87.9% (282/321) | 91.6% (846/924) |

Note: Mammography data was from Group B (women aged 40-69).

The study concluded that ABUS had a significantly higher specificity than HHUS (p<0.01), while HHUS had a higher sensitivity (p=0.01). When compared to mammography in women over 40, ABUS demonstrated significantly higher sensitivity (93.5% vs. 87.9%, p=0.02) with comparable specificity [11].

Impact of Breast Density

Breast density is a critical factor influencing diagnostic performance. Mammographic sensitivity decreases as breast density increases due to the masking effect of radiodense glandular tissue. A 2004 study found mammographic sensitivity could be as low as 45% in extremely dense breasts [30]. This is a key area where ABUS provides supplemental value.

A 2023 single-center retrospective study of 117 patients with core needle biopsy further underscored the complementary role of ABUS. The study found that while FFDM revealed 122 lesions, ABUS detected 246 focal lesions. The combined application of both methods increased sensitivity to 100% and improved overall diagnostic accuracy. Furthermore, ABUS showed higher compliance with histological tumor size measurements compared to FFDM [31].

Table 3: Performance in Dense Breasts and Combined Modality Use

| Scenario | Key Finding | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Mammography in Dense Breasts | Sensitivity can drop to ~45-55% in extremely dense breasts. | [30] |

| ABUS as Supplemental Screening | Increases cancer detection rate by 1.9–7.7 per 1000 women screened when combined with FFDM. | [4] |

| Combined FFDM + ABUS | Achieves 100% sensitivity, significantly improving over either modality alone. | [31] |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

For researchers designing experimental protocols or validating imaging biomarkers, a detailed understanding of the required materials and their functions is essential. The following toolkit outlines the key components for both imaging modalities.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for Imaging Protocols

| Item | Function in Protocol | Application / Modality |

|---|---|---|

| Full-Field Digital Mammography Unit | Core imaging device; acquires 2D digital images using ionizing radiation. | Mammography (FFDM) |

| Digital Breast Tomosynthesis Unit | Advanced mammography device; acquires 3D tomographic images via moving X-ray tube. | Mammography (DBT) |

| Automated Breast Ultrasound System | Core imaging device; performs automated volumetric scanning with dedicated transducer. | ABUS |

| Acoustic Coupling Gel | Ensures optimal transmission of ultrasound waves by eliminating air between transducer and skin. | ABUS |

| BI-RADS Atlas | Standardized lexicon for reporting and classifying breast imaging findings; critical for study consistency. | Mammography, ABUS |

| Computer-Aided Detection (CAD) Software | Assists radiologists by highlighting potentially abnormal areas (density, mass, calcification). | Mammography, ABUS |

| Sponge Wedge | Placed under patient's arm in supine position to evenly distribute breast tissue during ABUS scan. | ABUS |

| Phantom Test Objects | Quality control tools with simulated lesions to ensure consistent image quality and machine performance. | Mammography, ABUS |

Advantages, Limitations, and Research Implications

A balanced evaluation of both modalities must consider their inherent advantages and limitations, which directly inform their appropriate application in research and clinical practice.

Mammography:

- Advantages: Remains the gold standard for population-based screening with proven mortality reduction benefits. It is highly effective for detecting microcalcifications, a hallmark of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) [29]. Advanced techniques like DBT improve detection rates and reduce recall rates [29].

- Limitations: Involves ionizing radiation and breast compression, which can cause discomfort and deter participation. Its primary limitation is reduced sensitivity in dense breast tissue, which is a significant confounder in research studies involving pre-menopausal women [30].

ABUS:

- Advantages: Eliminates ionizing radiation and compression. It provides standardized, reproducible volumetric data, reducing operator-dependency. The coronal plane offers unique diagnostic information, and the modality demonstrates superior sensitivity in dense breasts [11] [4].

- Limitations: The acquisition can be challenged by very large breasts, requiring additional scan time and views. It cannot assess the axilla, vascularization, or lesion elasticity without Doppler or elastography functions available in HHUS. Image quality can be degraded by motion artifacts or poor positioning, and the interpretation time can be longer due to the large volumetric dataset [4].

The image acquisition processes for mammography and ABUS are fundamentally distinct, rooted in their different physical principles and leading to unique diagnostic profiles. Mammography, with its standardized compression and 2D/3D X-ray imaging, is an indispensable, proven screening tool, albeit with recognized limitations in dense breast tissue. ABUS offers a radiation-free, comfortable alternative that provides standardized, volumetric imaging of the breast with particular value for evaluating dense parenchyma.

Robust multicenter studies demonstrate that these modalities are not mutually exclusive but are powerfully complementary. ABUS has been shown to provide significantly higher sensitivity than mammography with comparable specificity, while also offering higher specificity than handheld ultrasound. For researchers and drug development professionals, this comparative analysis underscores the importance of modality selection based on specific research questions, patient populations (especially regarding breast density), and the critical need for standardized acquisition protocols to ensure reproducible and valid results in clinical trials and imaging studies. The integration of both technologies, alongside emerging artificial intelligence applications for ABUS analysis [20], represents the forward path in the personalized, early detection of breast cancer.

Breast cancer remains a significant global health challenge, being the most commonly diagnosed cancer with an estimated 2.3 million new cases worldwide [32]. In this context, early and accurate detection is paramount for improving treatment outcomes and patient survival. The diagnostic landscape relies on multiple imaging modalities, including digital mammography (MG), handheld ultrasound (HHUS), and the increasingly adopted automated breast ultrasound (ABUS). Each modality offers distinct advantages and limitations, particularly in different breast tissue densities and patient populations.

The Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS), developed by the American College of Radiology, serves as a critical framework for standardizing mammogram reports and providing clear, meaningful communication across healthcare facilities [33]. This system classifies findings into categories ranging from 0 (incomplete) to 6 (known biopsy-proven malignancy), with categories 4 and 5 indicating suspicious findings requiring pathological correlation [33]. As breast imaging evolves with new technologies, BI-RADS provides the essential lexicon and categorization system that enables consistent interpretation and management recommendations across different imaging modalities, making direct comparison of their performance both possible and clinically meaningful.

Performance Comparison Across Imaging Modalities

Cancer Detection Capabilities

Table 1: Cancer Detection Performance in Dense Breasts

| Imaging Modality | Cancer Detection Rate per 1000 Examinations | Recall Rate | Average Size of Detected Invasive Cancers | Study/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbreviated MRI | 17.4 (CI: 12.2-23.9) | 9.7% | 10 mm | BRAID RCT (2025) [34] |

| Contrast-Enhanced Mammography | 19.2 (CI: 13.7-26.1) | 9.7% | 11 mm | BRAID RCT (2025) [34] |

| Automated Breast Ultrasound | 4.2 (CI: 1.9-8.0) | 4.0% | 22 mm | BRAID RCT (2025) [34] |

| Full-Field Digital Mammography | 8.4 (CI: 7.2-9.9) | 5.4% | Not specified | BRAID RCT (2025) [34] |

The interim results from the large-scale BRAID randomized controlled trial (2025) provide compelling evidence regarding the comparative performance of supplemental imaging techniques in women with dense breasts and negative mammograms. As shown in Table 1, both abbreviated MRI and contrast-enhanced mammography demonstrated significantly higher cancer detection rates compared to ABUS, detecting approximately three times as many invasive cancers [34]. Crucially, the cancers detected by MRI and CEM were substantially smaller (10-11mm versus 22mm), suggesting potential for earlier detection when screening women with dense breasts [34].

BI-RADS Classification Concordance and Size Assessment

Table 2: BI-RADS Concordance and Pathological Size Correlation

| Comparison Metric | ABUS vs. HHUS | ABUS vs. MG | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BI-RADS Category Agreement | 86.63% (kappa = 0.77) | 32.22% (kappa = 0.10) | PMC Study (2021) [32] |

| Correlation with Pathological Size (Spearman) | 0.74 | 0.58 | PMC Study (2021) [32] |

| Size Assessment Accuracy (±5mm threshold) | 48.84% | 43.87% | PMC Study (2021) [32] |

| BI-RADS Category Agreement in Primary Care | 98.2% (kappa = 0.726) | ~96% (kappa = 0.21-0.25) | Frontiers (2025) [35] |

A 2021 study examining 344 confirmed malignant lesions provided detailed insights into the agreement between different modalities on BI-RADS categorization and lesion size assessment. The findings demonstrated excellent agreement between ABUS and HHUS in BI-RADS categorization (86.63%, kappa=0.77), indicating that these ultrasound-based modalities interpret lesion characteristics similarly [32]. In contrast, agreement between ABUS and mammography was notably poor (32.22%, kappa=0.10), highlighting the fundamental differences in how these technologies visualize and characterize breast tissue [32].

Both ABUS and HHUS showed superior correlation with pathological tumor size compared to mammography, with correlation coefficients of 0.75 and 0.74 respectively, versus 0.58 for MG [32]. This accurate size assessment is clinically significant for surgical planning and prognosis estimation.

Diagnostic Accuracy in Specific Clinical Scenarios

Table 3: Diagnostic Performance in BI-RADS 0 Recalls and Small Cancers

| Clinical Scenario | Modality | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI-RADS 0 Recalls | 3D ABUS | 72.1% | 84.4% | Missed 27.9% of malignancies detected by DBT/HHUS | Insights into Imaging (2024) [36] |

| BI-RADS 0 Recalls | DBT + HHUS | 100% | 71.4% | All malignancies detected | Insights into Imaging (2024) [36] |

| Small Cancers (≤1cm) | ABUS vs. HHUS | Maintained suspicion | - | 37.3% downcategorized vs. HHUS | Diagnostics (2025) [37] |

For small breast cancers (≤1cm), a 2025 study found that while ABUS maintained suspicion for malignancy in categories 4A or higher, it assigned lower BI-RADS categories compared to HHUS in 37.3% of cases [37]. This downcategorization, despite maintaining suspicious features, suggests that ABUS may depict less aggressive features for some small malignant lesions, potentially affecting clinical management decisions [37].

Methodological Approaches in Comparative Studies

Experimental Protocols for Modality Comparison

The following dot code illustrates a standardized experimental design for multi-modality imaging comparison studies:

Imaging Acquisition Protocols: Recent comparative studies have implemented rigorous standardization in image acquisition. For ABUS examinations, the Invenia ABUS system (GE Healthcare) is commonly employed with a 6-15 MHz transducer acquiring images in anteroposterior, lateral, and medial views [32] [37]. Patients are positioned supine with a sponge under the shoulder to evenly distribute breast tissue [32]. HHUS examinations typically utilize high-frequency linear transducers (10-15 MHz) with systematic overlapping scanning in radial and anti-radial planes [32]. Mammography follows standard mediolateral oblique and craniocaudal views using digital mammography or tomosynthesis systems [32].

Image Interpretation Methodology: Studies employed blinded reading protocols where radiologists specialized in breast imaging interpreted each modality separately without knowledge of other imaging results [32] [37]. BI-RADS categorization follows the standardized lexicon including shape, orientation, margin, echo pattern, posterior features, and calcifications [33]. Multiplanar reconstruction and review of ABUS images in transverse, sagittal, and coronal planes is essential for comprehensive evaluation [37].

Validation and Statistical Analysis: Pathological results from surgical specimens or biopsies serve as the reference standard, with lesion size defined as the maximum diameter [32]. Statistical analyses typically include kappa statistics for inter-modality agreement, correlation coefficients (Spearman) for size comparisons, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis for diagnostic performance [32] [35].

Emerging Methodological Innovations

Artificial Intelligence Integration: Deep learning approaches are increasingly applied to mammography interpretation, with one 2025 study demonstrating that a DL model could reduce unnecessary biopsies for BI-RADS 4A lesions by 55.1% while maintaining diagnostic accuracy [38]. Similarly, AI-based radiomics analysis of ABUS images shows promise in extracting high-dimensional quantitative features for improved tumor characterization [20].

Radiomics Workflow: The radiomics pipeline for ABUS involves image acquisition, preprocessing and tumor segmentation, feature extraction, feature selection, and model construction using either traditional machine learning or deep learning approaches [20]. This quantitative analysis complements traditional BI-RADS categorization by providing additional data on tumor heterogeneity and characteristics.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Modality Imaging Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| ABUS System | Automated 3D whole-breast ultrasound acquisition | Invenia ABUS (GE Healthcare) with 6-15 MHz transducer [32] |

| HHUS System | Handheld ultrasound for comparison | High-frequency linear array transducer (10-15 MHz) [32] |

| Digital Mammography System | Standard 2D mammography or tomosynthesis | Hologic Selenia Dimensions, GE Senographe DS [32] |

| BI-RADS Reference Guide | Standardized classification and lexicon | ACR BI-RADS Atlas, 5th Edition [33] |

| Pathology Consortium | Histopathological validation | Surgical specimen analysis, biomarker assessment (ER, PR, HER2) [32] |

| Dedicated Workstation | Multiplanar image review and analysis | ABUS review workstation with coronal reconstruction [37] |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Data analysis and agreement statistics | SPSS, R Studio with appropriate packages [32] |

The evidence from recent studies demonstrates that BI-RADS provides an essential standardized framework that enables meaningful comparison across breast imaging modalities. Each modality offers distinct advantages: mammography remains fundamental for microcalcification detection; ABUS provides standardized, reproducible whole-breast coverage with excellent correlation to HHUS; and advanced techniques like MRI and contrast-enhanced mammography show superior sensitivity in dense breasts.

The integration of artificial intelligence and radiomics holds promise for enhancing BI-RADS categorization, particularly for indeterminate lesions where biopsy reduction is desirable. Future directions should focus on optimizing modality selection based on individual patient factors, further refining BI-RADS categorization through quantitative imaging biomarkers, and developing integrated diagnostic pathways that leverage the complementary strengths of each imaging technology within a standardized BI-RADS framework.

For researchers and clinicians focused on breast cancer, dense breast tissue presents a significant diagnostic challenge. Full-field digital mammography (FFDM), the traditional cornerstone of breast screening, experiences a marked reduction in sensitivity in dense breasts, falling from over 85% in fatty breasts to as low as 61% in extremely dense tissue [39] [40]. This masking effect occurs because both fibroglandular tissue and malignancies appear radiographically white on a mammogram. Furthermore, dense breast tissue is an independent risk factor for breast cancer, with women possessing extremely dense breasts having a four to six times higher risk compared to those with fatty breasts [39] [40]. This dual problem of reduced detection sensitivity and increased intrinsic risk has driven the investigation of supplemental imaging modalities. Among these, Automated Breast Ultrasound (ABUS) has emerged as a promising technology, offering a standardized, operator-independent ultrasound approach. This guide provides a comparative analysis of ABUS's diagnostic performance against FFDM and other advanced modalities like contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM), with a specific focus on its application in high-risk and dense-breast populations.

Comparative Diagnostic Performance Data

The efficacy of any imaging modality is quantified by its sensitivity, specificity, and cancer detection rate. The data below, synthesized from recent studies, allows for a direct comparison of ABUS against established and emerging technologies.

Table 1: Comparative Diagnostic Performance in Dense Breasts (BI-RADS C & D)

| Imaging Modality | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Cancer Detection Rate (per 1000 screens) | Overall Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFDM (Mammography) | 61.8 - 85.4 [39] [40] | 91.9 [39] | Baseline | 66.1 - 83.3 [39] [40] |

| Handheld Ultrasound (HHUS) | 85.3 [39] | 88.4 [39] | +4.9 (as adjunct to FFDM) [41] | 87.1 [39] |

| ABUS | 78.1 - 93.8 [40] [42] | 40.0 - 88.2 [40] [42] | +1.9 - 2.4 (as adjunct to FFDM) [37] | 67.9 - 90.0 [40] [42] |

| Contrast-Enhanced Mammography (CEM) | 92.7 - 93.5 [43] [40] | 8.3 - 11.1 [43] [40] | 19.2 [44] | 73.6 - 80.0 [43] [40] |

| Abbreviated Breast MRI (AB-MRI) | Not Reported | Not Reported | 17.4 [44] | Not Reported |

| FFDM + ABUS Combination | 100 [43] [40] | Not Reported | Not Reported | 75.0 - 84.6 [43] [40] |

Table 2: Head-to-Head Comparison of Supplemental Imaging from the BRAID Trial

| Modality | Invasive Cancer Detection Rate (per 1000) | Typical Invasive Cancer Size Detected | Key Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABUS | 4.2 [44] | Larger (approx. twice the size of CEM/MRI-detected cancers) [44] | + No radiation or contrast- Lower detection rate for small invasive cancers |

| CEM | 15.7 [44] | Smaller (half the size of ABUS-detected cancers) [44] | + High detection rate- Iodinated contrast reactions (17 minor, 6 moderate, 1 severe per 1000) [44] |

| AB-MRI | 15.0 [44] | Smaller (half the size of ABUS-detected cancers) [44] | + High detection rate- Requires gadolinium contrast, higher cost |

Key Research Findings and Experimental Evidence

ABUS vs. Traditional Mammography and HHUS