Cancer Stem Cells: Decoding Their Central Role in Tumor Heterogeneity and Therapeutic Resistance

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are a pivotal subpopulation driving tumor initiation, progression, and relapse due to their self-renewal capacity, differentiation potential, and profound resistance to conventional therapies.

Cancer Stem Cells: Decoding Their Central Role in Tumor Heterogeneity and Therapeutic Resistance

Abstract

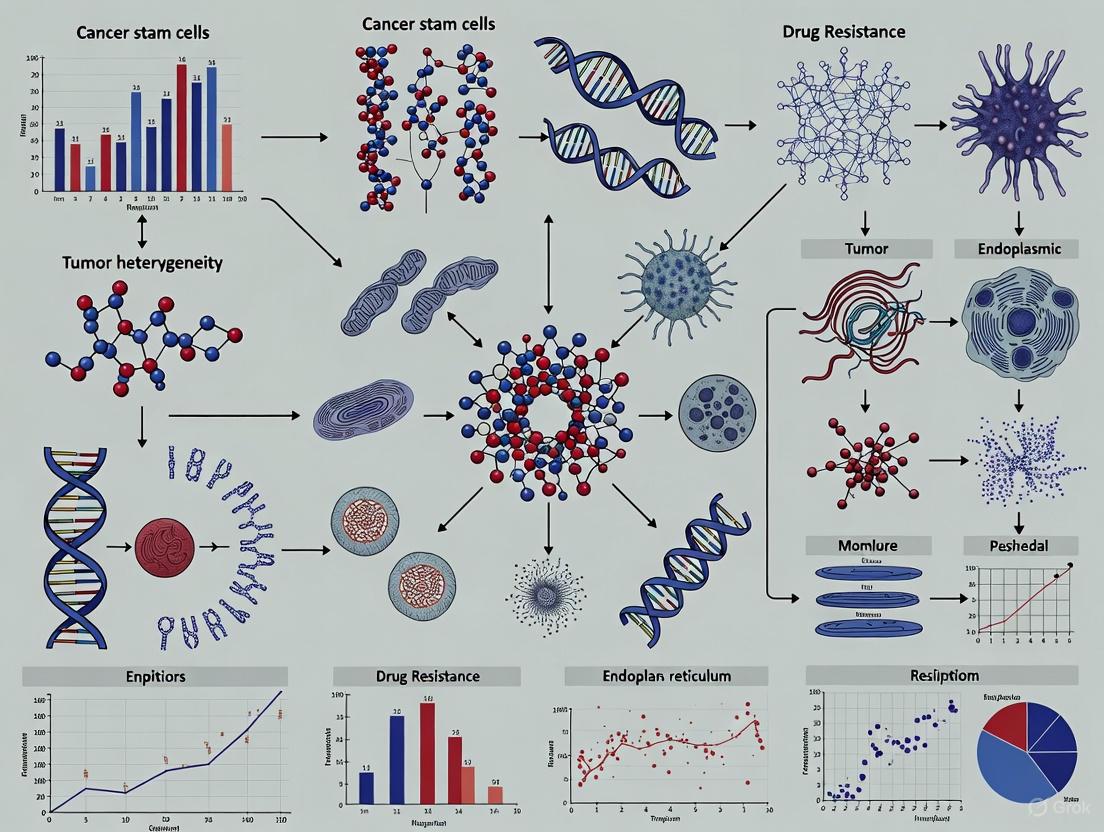

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are a pivotal subpopulation driving tumor initiation, progression, and relapse due to their self-renewal capacity, differentiation potential, and profound resistance to conventional therapies. This article synthesizes current research for an audience of researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the fundamental biology of CSCs, including their defining characteristics, key signaling pathways (Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, Hedgehog), and contributions to intratumoral heterogeneity. We detail advanced methodologies for CSC identification and isolation, examine the core mechanisms underlying their drug-resistant phenotype—such as quiescence, enhanced DNA repair, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and ABC transporter upregulation—and evaluate emerging therapeutic strategies. These innovations, including nanomaterial-based targeting, metabolic inhibitors, immunotherapy, and dual-pathway inhibition, are critically assessed for their potential to eradicate CSCs, overcome resistance, and improve clinical outcomes.

Deconstructing Cancer Stem Cells: The Architects of Tumor Heterogeneity and Relapse

Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) represent a functionally distinct subpopulation within tumors that drive tumor initiation, progression, therapeutic resistance, and recurrence [1] [2]. These cells exhibit core biological capabilities that define their pathogenic role in cancer biology: self-renewal, the ability to generate identical copies of themselves; differentiation, the capacity to produce heterogeneous lineages of cancer cells that constitute the tumor bulk; and tumorigenic potential, the capability to initiate and sustain tumor growth [2] [3]. These three hallmarks operate within a dynamic framework of cellular plasticity, enabled by the tumor microenvironment (TME) and underpinned by distinct molecular signaling pathways [2] [4]. Understanding these defining properties is fundamental to addressing the challenges of tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance in oncology research and therapeutic development [1] [5].

The CSC model fundamentally challenges previous conceptualizations of tumors as homogeneous masses, instead proposing a hierarchical organization wherein CSCs sit at the apex [3]. This review comprehensively examines the molecular mechanisms, experimental evidence, and research methodologies central to investigating the three defining hallmarks of CSCs, with particular emphasis on their role in fostering tumor heterogeneity and conferring resistance to conventional therapies.

Molecular Mechanisms Governing CSC Hallmarks

Core Signaling Pathways Regulating Self-Renewal and Plasticity

The hallmark capabilities of CSCs are maintained through the intricate operation of several evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways. These pathways, which are crucial for normal stem cell function and embryonic development, are frequently dysregulated in CSCs [6] [5].

Wnt/β-catenin Signaling: The Wnt pathway plays a pivotal role in maintaining CSC self-renewal [6] [5]. Upon Wnt ligand binding to the Frizzled receptor, the destruction complex (AXIN/GSK-3/APC) is inactivated, leading to β-catenin stabilization and its subsequent nuclear translocation [5]. In the nucleus, β-catenin associates with TCF/LEF transcription factors to activate target genes including MYC and CCND1, thereby promoting self-renewal and cell cycle progression [5]. Notably, β-catenin directly binds to the TERT promoter to enhance telomerase expression, maintaining telomere length—a critical feature for limitless replicative potential [5]. Non-canonical Wnt/Ca2+ signaling has also been implicated in promoting self-renewal and proliferation in colon CSCs [6].

Hedgehog (HH) Signaling: This pathway is integral to embryogenesis and tissue repair [5]. Hedgehog ligands (Sonic, Indian, and Desert) bind to Patched receptors, relieving inhibition of Smoothened and leading to activation of GLI transcription factors [5]. Activated GLI translocates to the nucleus and induces expression of genes governing cell survival, proliferation, and stemness maintenance [5]. Hedgehog signaling activation is also a known driver of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process closely linked to the acquisition of CSC properties [5].

Notch Signaling: Operating through direct cell-cell communication, Notch signaling is critical for cell fate decisions [5]. Ligand-receptor binding between adjacent cells triggers proteolytic cleavage of the Notch receptor, releasing the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) which translocates to the nucleus and forms a complex with CSL/RBP-Jκ to activate transcription of genes like HES and HEY [5]. With four receptors (Notch1-4) and five ligands (DLL1, DLL3, DLL4, Jagged-1, Jagged-2), this pathway demonstrates complex context-dependent regulation across cancer types [5].

JAK/STAT3, PI3-K/Akt, and Hippo/YAP1 Pathways: Additional pathways contribute significantly to the CSC phenotype. JAK/STAT3 and PI3-K/Akt signaling promote cell survival and growth [6] [7]. The Hippo pathway, particularly its effector YAP1, regulates CSC properties, chemo-resistance, and radio-resistance through targets including SOX9, EGFR, and CDK6 [4]. YAP1 also serves as a signaling hub integrating microenvironmental cues [4].

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways and their interconnections in maintaining CSC hallmarks:

Metabolic Programming Supporting CSC Function

CSCs exhibit remarkable metabolic plasticity that supports their hallmark functions [1] [7]. Unlike normal stem cells that primarily rely on glycolysis to minimize reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, CSCs actively utilize both glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to meet energy demands for tumor growth while maintaining stemness [7]. This metabolic flexibility allows CSCs to adapt to varying microenvironmental conditions, including hypoxia and nutrient deprivation [1]. Additional metabolic adaptations include upregulated lipid desaturation pathways to maintain stem cell-like properties, altered iron metabolism and ferroptosis sensitivity, and enhanced ceramide signaling to facilitate immune evasion [7]. These metabolic dependencies represent emerging vulnerabilities for therapeutic targeting.

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating CSC Hallmarks

Functional Assays for Quantifying Hallmark Capabilities

Rigorous experimental methodologies are essential for investigating the functional properties of CSCs. The table below summarizes key assays and their applications in CSC research:

Table 1: Core Functional Assays for Investigating CSC Hallmarks

| Hallmark | Assay Type | Key Readouts | Experimental Significance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Renewal | Sphere Formation Assay | Number and size of tumorspheres under non-adherent conditions | Measures clonal expansion and self-renewal capacity in vitro | [5] |

| In Vivo Limiting Dilution Assay | Tumor incidence and frequency of tumor-initiating cells | Quantifies self-renewal potential in immunocompromised mice | [5] [2] | |

| Tumorigenic Potential | Serial Transplantation Assay | Tumor formation capacity in secondary and tertiary recipients | Assesses long-term self-renewal and tumor-propagating ability | [2] [3] |

| In Vivo Tumor Initiation | Minimum cell number required for tumor formation | Measures potency for tumor initiation and growth | [2] [3] | |

| Differentiation | Lineage Tracing & Clonal Analysis | Heterogeneity of differentiated progeny from single CSCs | Demonstrates multi-lineage differentiation capacity | [3] |

| In Vitro Differentiation Assays | Expression of differentiation markers in adherent conditions | Evaluates potential to generate heterogeneous cancer cells | [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CSC Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Surface Marker Antibodies | Anti-CD44, Anti-CD133, Anti-CD34 | Identification and isolation of CSCs via FACS or MACS | Enables purification of CSC subpopulations for functional studies | [1] [4] [8] |

| Intracellular Marker Detection | ALDEFLUOR Assay, Anti-ALDH1 | Detection of aldehyde dehydrogenase activity | Identifies CSCs with enhanced detoxification capabilities | [5] [4] |

| Signaling Pathway Inhibitors | DKK1 (Wnt inhibitor), GANT61 (HH inhibitor), DAPT (Notch inhibitor) | Functional perturbation of stemness pathways | Determines pathway necessity for hallmark maintenance | [5] |

| Lineage Tracing Systems | Cre-lox, Fluorescent reporters (GFP, RFP) | Fate mapping of CSCs and their progeny | Tracks differentiation outcomes and cellular heterogeneity | [2] [3] |

| Cytokines & Growth Factors | TGF-β, EGF, bFGF, HGF | Modulation of CSC plasticity and EMT | Induces or maintains stem-like states in culture | [5] [3] |

The following workflow diagram illustrates a typical integrated experimental approach for characterizing CSC hallmarks:

CSC Hallmarks in Tumor Heterogeneity and Therapy Resistance

Generating and Sustaining Tumor Heterogeneity

The dual capabilities of self-renewal and differentiation enable CSCs to generate and maintain the complex cellular heterogeneity characteristic of malignant tumors [3]. Through asymmetric division, a single CSC can produce both an identical daughter stem cell and a progenitor cell committed to differentiation, thereby establishing a cellular hierarchy within the tumor [2] [3]. This hierarchy results in intratumoral heterogeneity—variations observed within a single tumor—including diverse cell surface markers, genetic and epigenetic changes, growth rates, and metastatic potential among different subpopulations [3]. Recent spatial transcriptomics studies have further revealed that this heterogeneity is spatially organized, with distinct regions of tumors exhibiting different hallmark activities and molecular profiles [9].

The plasticity of CSCs significantly amplifies this heterogeneity. Non-stem cancer cells can regain stemness characteristics through dedifferentiation processes, often induced by microenvironmental cues such as hypoxia, inflammation, or therapeutic pressure [1] [3]. Key transcription factors including OCT3/4, SOX2, NANOG, and KLF4 are frequently overexpressed in CSCs and contribute to this plasticity by maintaining pluripotency networks [8]. This dynamic interconversion between stem and non-stem states creates a continuous source of cellular diversity that complicates therapeutic targeting and promotes tumor adaptation.

Mechanisms of Therapy Resistance

CSCs employ multiple mechanisms to resist conventional cancer therapies, largely rooted in their defining hallmarks:

Quiescence and Dormancy: Many CSCs reside in a quiescent, non-dividing state (G0 phase), making them insensitive to therapies that target rapidly proliferating cells [5]. This dormancy provides time for DNA repair and survival under therapeutic stress [5] [4]. Strategies to "wake up" CSCs, such as Fbxw7 ablation or PPAR-γ agonism, have shown promise in sensitizing them to subsequent treatment [5].

Enhanced DNA Repair Capacity: CSCs exhibit heightened DNA damage response mechanisms, including constitutive activation of checkpoint pathways, enabling efficient repair of therapy-induced DNA lesions [5]. This is particularly relevant for radiotherapy and DNA-damaging chemotherapeutics.

Drug Efflux Transporters: High expression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters such as ABCB5 and ABCG2 allows CSCs to actively expel chemotherapeutic agents, conferring multidrug resistance [5] [7] [4].

Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT): The EMT program, closely associated with CSC states, promotes therapy resistance through multiple mechanisms including induction of quiescence, upregulation of survival pathways, and enhanced interaction with protective microenvironments [5].

Metabolic Adaptations: The metabolic plasticity of CSCs enables them to switch between energy production pathways to survive under diverse conditions, including hypoxic regions of tumors that are poorly penetrated by therapeutics [1] [7].

The defining hallmarks of CSCs—self-renewal, differentiation, and tumorigenic potential—establish these cells as central drivers of tumor heterogeneity, progression, and therapeutic resistance. Understanding the molecular underpinnings of these capabilities provides critical insights for developing more effective cancer treatments. Current research is increasingly focused on targeting the unique vulnerabilities of CSCs, including their signaling dependencies, metabolic adaptations, and interactions with the tumor microenvironment [1] [2].

Emerging therapeutic approaches include dual metabolic inhibition to overcome metabolic plasticity, synthetic biology-based interventions, immune-based strategies such as CSC-targeted CAR-T cells, and nanotechnology-enabled drug delivery systems designed to specifically target CSCs [1] [10]. The integration of single-cell multi-omics, spatial transcriptomics, and AI-driven analysis holds promise for unraveling the complexity of CSC biology and identifying novel therapeutic targets [1] [9]. As these advanced technologies and targeted strategies mature, they offer the potential to overcome CSC-mediated therapy resistance and significantly improve outcomes for cancer patients.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) constitute a highly plastic and therapy-resistant cell subpopulation within tumors that drives tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and relapse [1]. These cells demonstrate capacities for self-renewal, differentiation, and tumor initiation, contributing significantly to intratumoral heterogeneity and treatment failure [11] [1]. The identification and characterization of CSCs rely heavily on specific cellular biomarkers, which serve not only as identification tools but also as potential therapeutic targets. Among the most extensively studied CSC markers are the surface proteins CD44, CD133, ALDH1, and EpCAM, each playing distinct roles in CSC biology across various cancer types [11] [1].

The clinical significance of CSC biomarkers extends beyond basic identification, offering potential prognostic value and insights into therapy resistance mechanisms. However, a major challenge in the field is the lack of universal CSC markers, as their expression and functional significance vary considerably across different tumor types and even within subtypes of the same cancer [1]. This variability reflects the profound influence of tissue origin and microenvironmental context on CSC phenotypes, necessitating a nuanced understanding of each marker's specific roles and interactions.

Marker Profiles and Biological Functions

Individual Marker Characteristics

CD44: A cell surface glycoprotein receptor for hyaluronic acid, CD44 is strongly involved in cancer cell adhesion, migration, and metastasis [12]. It has been used to identify putative CSCs in various tumor types including breast, prostate, pancreatic, and head and neck carcinomas [12]. CD44 positive populations often demonstrate more robust colony formation, higher proliferation, less spontaneous apoptosis, and higher resistance to drug-induced cell death [13].

CD133 (Prominin-1): A transmembrane glycoprotein that localizes to cellular protrusions, CD133 was one of the first CSC markers identified in various solid tumors [14]. Its expression alone may not always define the CSC population, as in some colorectal cancers where CD133 expression is detectable in a large majority of tumor cells irrespective of their tumorigenicity [14]. However, in lung adenocarcinoma, CD133 expression specifically correlates with poorer overall survival and shorter disease-free interval [15].

ALDH1 (Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1): This cytosolic enzyme plays a key role in oxidizing intracellular aldehydes and converting retinol to retinoic acid in early stem cell differentiation [12]. ALDH1 activity serves as a functional marker for stem-like properties, with ALDH1-bright cells demonstrating enhanced drug resistance and tumorigenic potential in ovarian cancer models [16]. In oral cancer, ALDH1 expression increases with dysplasia progression, suggesting its utility as a specific marker for malignant transformation [12].

EpCAM (Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule): A transmembrane glycoprotein that mediates homotypic calcium-independent cell adhesion in epithelia [14]. Interestingly, in colorectal cancer, loss rather than overexpression of membranous EpCAM is linked to tumor progression, supporting the notion that membranous evaluation may represent cell adhesion functions rather than intracellular signaling [14].

Table 1: Core CSC Biomarkers and Their Functional Roles

| Biomarker | Type | Primary Localization | Key Functions | Associated Cancers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD44 | Surface glycoprotein | Cell membrane | Cell adhesion, migration, metastasis, drug resistance | Breast, ovarian, colorectal, HNSCC |

| CD133 | Transmembrane glycoprotein | Cellular protrusions | Maintenance of stem cell properties, potential interaction with membrane lipids | Lung, colorectal, glioblastoma |

| ALDH1 | Metabolic enzyme | Cytoplasm | Detoxification, retinoic acid production, chemoresistance | Ovarian, lung, oral, HNSCC |

| EpCAM | Cell adhesion molecule | Cell membrane | Homotypic cell adhesion, intracellular signaling | Colorectal, pancreatic, breast |

Combinatorial Marker Profiles

Research increasingly indicates that combinatorial marker profiles rather than single markers better define CSC populations across different cancer types. The specific combinations vary significantly between tissues and cancer types:

In colorectal cancer, the CD44+CD133- subpopulation in SW620 cells correlates with most CSC features, including enhanced migration and invasion capabilities [13]. This profile aligns with CSC phenotypes in other tumors such as CD44+CD24- for breast and pancreatic tumors and CD34+CD38- for acute myeloid leukemia [13].

In ovarian cancer, ALDH1-bright cells are associated with CD44 expression, with ALDH1br cells showing greater enrichment in CD44 (by 1.74-fold to 5.18-fold) than in CD133 (by 1.39-fold to 1.17-fold) compared with ALDH1low cells [16]. This co-expression pattern underscores the potential synergy between different CSC markers in defining the most tumorigenic cell populations.

Table 2: Clinically Significant CSC Marker Combinations in Different Cancers

| Cancer Type | Marker Combination | Clinical/Prognostic Association |

|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer | CD44+CD133- | Enhanced migration, invasion, and colony formation [13] |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | ALDH1A1+/CD133+ | Poor overall survival and shorter disease-free interval [15] |

| Ovarian Cancer | ALDH1br/CD44+ | Drug resistance, poor clinical outcome [16] |

| Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | ALDH1+/CD44+ | Association with dysplasia and lymph node metastasis [12] |

| Acute Myeloid Leukemia | CD34+CD38- | Leukemia-initiating potential [1] |

Methodologies for CSC Marker Analysis

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) represents a cornerstone technique for evaluating CSC marker expression in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections, allowing for correlation with clinicopathological parameters. The methodology involves several critical steps:

- Tissue Preparation: Sections of 3-4μm thickness are mounted on slides, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated through a graded alcohol series [12] [15].

- Antigen Retrieval: Heat-induced epitope retrieval is performed using citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 121°C for 30 minutes under pressure [12].

- Antibody Incubation: Primary antibodies are applied with specific concentrations: anti-CD44 (clone DF1485, ready-to-use) [12], anti-CD133 (clone C24B9; 1:100) [14], anti-ALDH1 (polyclonal; 1:500) [14], and anti-EpCAM (clone VU-1D9; 1:200) [14].

- Detection and Visualization: Following secondary antibody application, 3,3'-diaminobenzidine-tetrahydrochloride (DAB) is used as a chromogen, followed by counterstaining with Mayer's hematoxylin [12].

Scoring methodologies vary by marker localization pattern. For CD133, CD166, CD44s, and EpCAM, membranous staining is evaluated, while for ALDH1, cytoplasmic immunoreactivity is assessed [14]. Scoring typically involves semi-quantitative assessment of the percentage of positive tumor cells, often using cutoff values determined by receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for prognostic studies [14].

Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) enables isolation of live CSC subpopulations for functional characterization, using the following standard protocol:

- Cell Preparation: Single-cell suspensions are obtained from cell lines or dissociated tumor tissues [13].

- Antibody Staining: Cells are incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CSC markers (e.g., PE-conjugated anti-CD133, FITC-conjugated anti-CD44) for 1 hour at 4°C in the dark [13].

- Viability Staining: Propidium iodide (1μg/ml) is added to exclude dead cells during sorting [13].

- Cell Sorting: Subpopulations are isolated based on marker expression profiles (e.g., CD133+CD44+, CD133+CD44-, CD133-CD44+, and CD133-CD44-) using a flow cytometer [13].

- Functional Assays: Sorted populations are subsequently subjected to colony formation, drug resistance, migration, and invasion assays [13].

The Aldefluor assay provides a functional approach to identify cells with high ALDH enzymatic activity [16]. This assay utilizes a fluorescent substrate that is converted and retained in cells with high ALDH activity, allowing isolation of ALDH1-bright populations that demonstrate stem-like properties.

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for CSC Marker Analysis and Functional Validation

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CSC Marker Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application Purpose | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Anti-CD44 (clone DF1485) [12], Anti-CD133 (clone C24B9) [14], Anti-ALDH1 (polyclonal) [14], Anti-EpCAM (clone VU-1D9) [14] | IHC, Western blot, flow cytometry | Validate for specific applications; concentrations vary (e.g., 1:50-1:500 for IHC) |

| Fluorochrome-Conjugated Antibodies | PE-conjugated anti-CD133, FITC-conjugated anti-CD44, eFluor 660-conjugated anti-ESA [13] | Flow cytometry, FACS | Include isotypic controls and unstained cells as negative controls |

| Cell Separation Tools | Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) [13], Aldefluor Assay Kit [16] | Isolation of live CSC subpopulations | Purity of sorted cells should be ≥97%; include viability staining (PI or DAPI) |

| Cell Culture Assays | CyQuant cell proliferation assay [13], Caspase-Glo assay [13], BD BioCoat Tumor Invasion System [13] | Functional characterization of CSCs | Serum-free medium for invasion assays; matrigel-coated membranes |

| Cell Lines | SW620, Colo205, LS180 (colorectal) [13] [14]; ES-2, TOV-21G, CP70 (ovarian) [16] | In vitro CSC studies | Authenticate cell lines regularly; check marker expression profiles |

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Applications

Prognostic Significance

CSC marker expression demonstrates significant correlations with clinical outcomes across various malignancies, although these relationships can be complex and context-dependent:

In ovarian cancer, patients with higher ALDH1 expression (>50% positive cells) demonstrate significantly poorer overall survival compared with those with lower ALDH1 expression, with multivariate analysis yielding an odds ratio of death of 2.43 [16]. This association between ALDH1 and poor outcome underscores its potential utility as a prognostic biomarker.

In lung adenocarcinoma, CD133 expression specifically correlates with poorer overall survival and shorter disease-free interval, with multivariate analysis revealing that double negativity for ALDH1A1 and CD133 is independently associated with increased survival and longer disease-free interval [15].

Unexpectedly, in colorectal cancer, loss rather than overexpression of membranous CD44s and CD166 is associated with higher pT and pN stages, infiltrating growth pattern, and worse survival [14]. This paradoxical finding highlights the importance of considering the specific cellular localization and function of these markers, as membranous evaluation may primarily reflect cell adhesion functions rather than intracellular signaling roles.

Role in Drug Resistance

CSCs contribute significantly to therapy resistance through multiple interconnected mechanisms, making their marker profiles potentially valuable for predicting treatment response:

Chemoresistance: ALDH1-bright ovarian cancer cells demonstrate significant resistance to conventional chemotherapeutic agents, with ALDH1br cells maintaining viability after drug exposure that eliminates the majority of tumor cells [16]. Similarly, CD44 positive cells in colorectal cancer show higher resistance to drug-induced cell death and become enriched after drug treatment [13].

Radiation Resistance: CSCs generally exhibit enhanced DNA repair capacity and resistance to radiation-induced apoptosis, contributing to tumor recurrence after radiotherapy [1].

Multidrug Resistance Phenotypes: CSCs frequently overexpress ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters that efflux chemotherapeutic drugs, along with enhanced detoxification systems including ALDH1 activity [1] [17].

Figure 2: CSC-Associated Therapy Resistance Mechanisms Leading to Recurrence

Emerging Research and Future Directions

The landscape of CSC research continues to evolve with emerging technologies enabling more precise characterization of these critical cell populations. Single-cell sequencing and spatial transcriptomics are significantly advancing our understanding of CSC heterogeneity and plasticity, revealing how stem-like features can be acquired de novo by non-CSCs in response to environmental stimuli [1]. These findings challenge the notion of a fixed CSC hierarchy and highlight CSC phenotypes as dynamic functional states influenced by microenvironmental cues.

The development of 3D organoid models and CRISPR-based functional screens is paving the way for more physiologically relevant studies of CSC biology and drug resistance mechanisms [1]. These platforms enable more accurate modeling of tumor heterogeneity and microenvironmental interactions, potentially leading to more effective therapeutic strategies.

Emerging therapeutic approaches focus on targeting CSC vulnerabilities through dual metabolic inhibition, synthetic biology-based interventions, and immune-based strategies [1]. The integration of CSC biomarkers with artificial intelligence-driven multiomics analysis holds promise for developing personalized treatment approaches that effectively target both the bulk tumor and therapy-resistant CSC populations [1].

As research progresses, the combinatorial analysis of multiple CSC markers within specific tumor contexts will be essential for developing more effective prognostic tools and therapeutic strategies. The future of CSC-targeted therapy likely lies in integrated approaches that simultaneously address multiple resistance mechanisms while accounting for the dynamic plasticity of CSC populations within diverse tumor microenvironments.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) represent a subpopulation of tumor cells with capabilities for self-renewal, differentiation, and tumor initiation, driving intra-tumoral heterogeneity, therapeutic resistance, and cancer recurrence. The functional properties of CSCs are governed by an intricate network of conserved signaling pathways. This technical review examines the core regulatory circuits of Wnt/β-catenin, Hedgehog (Hh), Notch, and Hippo/YAP signaling, detailing their mechanisms, crosstalk, and roles in maintaining CSC functionality. The document provides structured quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and visualization tools to support research and therapeutic development efforts aimed at overcoming CSC-mediated drug resistance. Framed within the broader context of CSC biology, this resource equips scientists with foundational knowledge and practical references for targeting these pathways in precision oncology.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are a functionally distinct subpopulation within tumors that possess stem cell-like properties, including self-renewal, differentiation capacity, and tumor-initiating potential [18] [2]. First identified in acute myeloid leukemia and subsequently isolated in various solid tumors, CSCs contribute significantly to tumor heterogeneity, metastatic dissemination, and resistance to conventional therapies [18] [19]. Their ability to persist after treatment and drive recurrence underscores their clinical importance in oncology research and drug development.

The molecular identity and maintenance of CSCs are regulated by key developmental signaling pathways that are often dysregulated in cancer. The Wnt/β-catenin, Hedgehog, Notch, and Hippo/YAP pathways represent core regulatory systems that control CSC self-renewal, metabolic adaptation, and interactions with the tumor microenvironment [18] [20] [21]. These pathways exhibit extensive crosstalk, forming an integrated network that maintains CSC plasticity and survival under therapeutic stress [22] [19]. This review systematically examines each pathway's architecture, regulatory mechanisms, and experimental approaches for their investigation, with particular emphasis on their collective role in sustaining CSC functionality and promoting treatment resistance.

Pathway Mechanisms and Dysregulation in Cancer

Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is a highly conserved system regulating cell fate determination, tissue homeostasis, and stem cell maintenance. In the canonical pathway, binding of Wnt ligands to Frizzled receptors and LRP co-receptors inhibits the destruction complex (APC, Axin, GSK-3β, CK1α), preventing β-catenin phosphorylation and degradation [18] [20]. Stabilized β-catenin accumulates and translocates to the nucleus, where it partners with TCF/LEF transcription factors to activate target genes including c-MYC, CYCLIN D1, and CD44 that promote self-renewal and proliferation [18] [21].

In CSCs, Wnt/β-catenin signaling is frequently hyperactivated, enhancing CSC self-renewal and therapeutic resistance [18] [23]. The pathway exhibits crosstalk with Hippo/YAP signaling, where YAP/TAZ can interact with β-catenin to reinforce transcriptional programs supporting stemness [22] [21]. Dysregulation occurs through multiple mechanisms, including mutations in pathway components (APC, β-catenin), autocrine Wnt signaling, and Wnt production from tumor-associated stromal cells [18].

Table 1: Core Components of Wnt/β-catenin Signaling Pathway

| Component Type | Key Elements | Functional Role in Pathway | Cancer Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligands/Receptors | Wnt ligands, Frizzled, LRP5/6 | Signal initiation and receptor complex formation | Overexpression in colorectal, breast cancer |

| Destruction Complex | APC, Axin, GSK-3β, CK1α | β-catenin phosphorylation and degradation | APC mutations in colorectal cancer |

| Effectors | β-catenin, TCF/LEF | Transcriptional activation of target genes | β-catenin mutations in hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Target Genes | c-MYC, CYCLIN D1, CD44, AXIN2 | Regulation of cell cycle, stemness, metastasis | Elevated in various CSCs |

| Regulatory Proteins | DKK, SFRP | Natural pathway inhibitors | Epigenetic silencing in cancers |

Hedgehog Signaling Pathway

The Hedgehog (Hh) pathway is crucial for embryonic patterning, tissue repair, and stem cell maintenance. In the canonical pathway, Hh ligand binding to Patched (PTCH1) relieves its inhibition of Smoothened (SMO), leading to activation of GLI transcription factors (GLI1, GLI2, GLI3) that regulate target genes including BCL-2, CYCLIN D, and MYC [20]. In CSCs, Hh signaling promotes self-renewal, survival, and metabolic adaptations that support therapy resistance [18] [20].

Hh pathway dysregulation in cancer occurs through ligand-dependent mechanisms (paracrine signaling from tumor microenvironment) or ligand-independent mechanisms (mutations in PTCH1, SMO, SUFU) [20]. The pathway demonstrates significant crosstalk with Hippo/YAP signaling; for instance, in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, microRNA-301a mediates interplay between Hh and Hippo pathways to promote progression [22].

Notch Signaling Pathway

Notch signaling mediates cell-cell communication and fate determination through proteolytic cleavage events. Canonical activation involves Delta/Serrate/LAG-2 (DSL) ligand binding, followed by γ-secretase-mediated cleavage of Notch receptors, releasing the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) that translocates to the nucleus and partners with CSL transcription factors to activate target genes including HES, HEY, and MYC [18] [20].

In CSCs, Notch signaling maintains the undifferentiated state and promotes survival through regulation of apoptosis inhibitors and EMT transcription factors [18] [23]. The pathway exhibits contextual oncogenic or tumor-suppressive functions depending on tissue type and cellular context. Notch crosstalk with Hippo/YAP occurs through multiple mechanisms, including YAP/TAZ enhancement of NOTCH receptor expression and collaborative regulation of shared target genes [22].

Hippo/YAP Signaling Pathway

The Hippo/YAP pathway is an evolutionarily conserved kinase cascade that controls organ size, cell proliferation, and stem cell function. In the canonical pathway, upstream signals activate MST1/2 kinases, which phosphorylate LATS1/2, leading to phosphorylation and cytoplasmic retention or degradation of YAP/TAZ effectors [22] [24]. When the pathway is inactive, unphosphorylated YAP/TAZ translocate to the nucleus and partner with TEAD transcription factors to activate target genes including CTGF, CYR61, and BIRC5 that promote cell growth and survival [22] [24].

In CSCs, Hippo/YAP signaling enhances self-renewal, metabolic reprogramming, and therapy resistance. YAP/TAZ activity supports CSC maintenance through regulation of glutamine metabolism and interaction with key stemness transcription factors [22]. The pathway exhibits extensive crosstalk, integrating with Wnt, TGF-β, NF-κB, and Hedgehog signaling to form a complex regulatory network that influences CSC plasticity and tumorigenicity [22] [21].

Table 2: Pathway Crosstalk in Cancer Stem Cell Regulation

| Signaling Pathway | Crosstalk Mechanisms | Functional Consequences in CSCs | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hippo-YAP & Wnt | YAP/TAZ interact with β-catenin/DVL; shared target gene regulation | Enhanced self-renewal, EMT promotion, metabolic reprogramming | Combined YAP/β-catenin inhibition strategies |

| Hippo-YAP & TGF-β | SMAD-TEAD complexes; YAP-TGF-β synergy in EMT | Stemness maintenance, immune evasion, metastasis | Dual SMAD/YAP targeting in metastatic disease |

| Hippo-YAP & Hedgehog | microRNA-mediated crosstalk (e.g., miR-301a); GLI-YAP interactions | Pancreatic cancer progression, therapy resistance | Combinatorial SMO/YAP inhibitors |

| Hippo-YAP & Notch | YAP enhancement of NOTCH receptor expression; TEAD-NOTCH collaboration | Regulation of stem cell fate decisions, differentiation control | Context-dependent combination therapies |

| Hippo-YAP & NF-κB | YAP as NF-κB co-activator; inflammatory gene regulation | Osteoclastogenesis, immune modulation, bone metastasis | YAP/NF-κB targeting in inflammatory cancers |

Experimental Approaches for Pathway Analysis

Core Methodologies for Signaling Pathway Investigation

Investigation of CSC signaling pathways requires integrated experimental approaches spanning molecular, cellular, and functional assays. Gene expression profiling using RNA-seq and single-cell RNA-seq enables comprehensive analysis of pathway activity states and heterogeneity within CSC populations [1] [2]. Protein localization and quantification through immunohistochemistry, western blotting, and flow cytometry provide critical data on pathway activation status, particularly for YAP/TAZ nuclear translocation and β-catenin accumulation [24].

Functional pathway analysis employs reporter assays (TOPFlash for Wnt, GLI-luciferase for Hh, TEAD-luciferase for Hippo) to quantify transcriptional activity [24]. CRISPR-based functional screens enable systematic identification of essential pathway components and regulators in specific CSC contexts [1] [18]. Additionally, 3D organoid cultures and patient-derived xenograft models provide physiologically relevant systems for evaluating pathway functions in CSC maintenance and therapeutic response [1] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Pathway Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Reporters | TOPFlash (Wnt), GLI-luciferase (Hh), TEAD-luciferase (Hippo), CBF1-luciferase (Notch) | Quantitative pathway activity measurement | Normalize to control reporters; context-dependent specificity |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | IWR/IWP (Wnt), GANT61 (Hh), DAPT (Notch), Verteporfin (YAP) | Pathway inhibition and functional validation | Assess specificity and off-target effects |

| Activation Compounds | CHIR99021 (Wnt), SAG (Hh), Recombinant DLL/JAG (Notch) | Experimental pathway stimulation | Concentration optimization critical |

| Antibodies | Anti-β-catenin, anti-YAP/TAZ, anti-GLI1, anti-NICD | Protein localization and quantification | Phospho-specific antibodies for activation status |

| CRISPR Tools | sgRNA libraries, Cas9 variants, base editors | Functional genetic screening | Use multiple sgRNAs per gene to confirm findings |

Therapeutic Targeting and Clinical Implications

The strategic targeting of CSC signaling pathways represents a promising approach to overcome therapy resistance and prevent tumor recurrence. Current therapeutic development focuses on several key strategies: small molecule inhibitors targeting critical pathway nodes (SMO in Hh, γ-secretase in Notch, TEAD-YAP interaction in Hippo) [22] [24] [20]; monoclonal antibodies against pathway ligands and receptors; natural compounds with multi-pathway activity; and combination approaches that target complementary pathways or combine pathway inhibition with conventional therapies [24] [23].

Clinical challenges in targeting CSC pathways include pathway crosstalk and compensatory activation, tissue-specific toxicities due to pathway roles in normal stem cell maintenance, and the dynamic plasticity of CSCs that enables adaptation to targeted therapies [1] [18]. Emerging solutions incorporate pharmacological modulation of multiple pathways, biomarker-driven patient stratification, and nanotechnology-based delivery systems to enhance specificity and reduce toxicity [2] [20]. The integration of AI-driven multiomics analysis and advanced disease modeling continues to refine therapeutic targeting strategies for improved clinical outcomes [1] [18].

The Wnt/β-catenin, Hedgehog, Notch, and Hippo/YAP signaling pathways constitute fundamental regulatory networks that maintain CSC populations and drive tumor heterogeneity, therapy resistance, and metastatic progression. Understanding the intricate mechanisms, contextual functions, and extensive crosstalk among these pathways provides critical insights for developing targeted therapeutic interventions. Future research directions should emphasize multi-pathway targeting approaches, advanced modeling of CSC-TME interactions, and translational strategies that leverage emerging technologies in single-cell analysis, computational modeling, and precision drug delivery. By dismantling the signaling foundations that sustain CSCs, the oncology research community can advance toward more effective and durable cancer treatments.

The cancer stem cell (CSC) paradigm has fundamentally transformed our understanding of tumorigenesis, progression, and therapeutic resistance. Historically, CSCs were viewed as a static hierarchical compartment situated at the apex of a rigid cellular organization within tumors. However, emerging evidence has dramatically reshaped this concept, revealing that CSCs exist in a state of dynamic equilibrium with their non-stem cancer cell (NSCC) counterparts [25] [26]. This continuous, bidirectional interconversion between CSC and NSCC states—termed cancer stem cell plasticity—represents a critical adaptive mechanism that fuels tumor heterogeneity, enables metastatic dissemination, and undermines conventional therapies [2] [4].

The plasticity paradigm posits that stemness is not a fixed cellular attribute but rather a transient, context-dependent state that can be acquired or relinquished based on cell-intrinsic signals and microenvironmental cues [25]. This fluidity complicates therapeutic targeting of CSCs and provides tumors with a resilient reservoir for regeneration following treatment. This review examines the molecular drivers, regulatory mechanisms, and functional implications of CSC-NSCC interconversion, framing this plasticity within the broader context of tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance research.

Molecular Mechanisms Governing Plasticity

Key Signaling Pathways and Transcriptional Networks

The dynamic interconversion between CSCs and NSCCs is orchestrated by complex signaling networks and transcriptional programs that respond to both intrinsic and extrinsic cues.

Table 1: Core Signaling Pathways Regulating CSC Plasticity

| Pathway | Key Components | Role in Plasticity | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wnt/β-catenin | Frizzled receptors, β-catenin, GSK-3, APC | Enhances self-renewal; maintains stemness; stabilizes telomeres via TERT [5] | Wnt inhibitors in development; challenges with on-target toxicity |

| Hedgehog | Smoothened, GLI transcription factors | Induces EMT; promotes therapy resistance; regulates cell survival [5] | Smoothened inhibitors (e.g., vismodegib) show efficacy in basal cell carcinoma |

| Notch | Notch 1-4 receptors, DLL/Jagged ligands | Maintains stemness through cell-cell communication; influences cell fate decisions [5] | Notch signaling inhibitors being evaluated in clinical trials |

| TGF-β | TGF-β ligands, SMAD proteins | Primary inducer of EMT; accelerates CSC-NSCC equilibrium [27] | TGF-β inhibitors can disturb plasticity equilibrium |

| Hippo/YAP1 | YAP1, TAZ, MST1/2, LATS1/2 | Regulates stem cell maintenance; confers therapy resistance; nuclear YAP1 associated with poor prognosis [4] | YAP1 inhibition restores drug sensitivity in resistant models |

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) program serves as a master regulator of CSC plasticity, enabling epithelial cells to acquire mesenchymal traits including enhanced motility, invasiveness, and stem-like properties [28]. EMT is not a binary process but rather a spectrum of intermediate states, with hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal (E/M) phenotypes often exhibiting the highest stemness potential [29]. This plasticity is maintained by double-negative feedback loops, such as the Snail/miR-34 and Zeb/miR-200 circuits, which create toggle switches enabling reversible phenotypic transitions [28].

Epigenetic Regulation and Metabolic Adaptations

Epigenetic mechanisms serve as crucial mediators of CSC plasticity, allowing rapid phenotypic switching without permanent genetic alterations. DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling enable dynamic reprogramming of gene expression patterns in response to therapeutic stress or microenvironmental changes [25] [2]. Additionally, CSCs exhibit metabolic plasticity, shifting between oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis, and fatty acid oxidation to meet energy demands and mitigate oxidative stress under various conditions [2]. This metabolic flexibility supports survival during therapeutic challenges and facilitates transitions between stem and non-stem states.

Figure 1: Molecular Network Regulating CSC Plasticity. Multiple signaling pathways converge on EMT transcription factors and epigenetic regulators to enable bidirectional interconversion between cellular states.

Experimental Evidence and Methodological Approaches

Key Studies Demonstrating Dynamic Interconversion

Seminal research has provided compelling evidence for the spontaneous interconversion between CSCs and NSCCs across multiple cancer types:

Colon and Breast Cancer Models: SW620 colon cancer and MCF-7 breast cancer cells maintain constant CSC proportions over multiple generations despite sorting for CSC and NSCC populations, indicating continuous repopulation through bidirectional conversion [27]. This equilibrium is maintained irrespective of prior radiation exposure, demonstrating the resilience of plasticity mechanisms.

Glioblastoma Plasticity: CSC markers (CD133, A2B5, SSEA, CD15) do not represent clonal entities but rather plastic states that can be adapted by most cells in response to microenvironmental conditions [26]. This dynamic state enables rapid adaptation to therapeutic pressures.

Melanoma Phenotypic Switching: JARID1B-positive melanoma CSCs and JARID1B-negative cells undergo reversible phenotypic changes, with negative cells capable of re-expressing the marker and regenerating tumor heterogeneity [26].

Colorectal Cancer Lineage Tracing: Targeted ablation of Lgr5+ CSCs does not lead to tumor regression because Lgr5− cells can regenerate the Lgr5+ population, demonstrating the reversible nature of the stem cell state [26] [30].

Table 2: Quantitative Evidence for CSC-NSCC Interconversion

| Cancer Type | Experimental System | CSC Markers | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon Cancer | SW620 cell line | CD133 | Spontaneous reconstitution of both CSC and NSCC populations from purified fractions within days | [27] |

| Breast Cancer | MCF-7 cell line | CD44+/CD24− | Dynamic equilibrium maintained between cellular states across multiple generations | [27] |

| Glioblastoma | Patient-derived samples | CD133, A2B5, SSEA | Marker expression represents plastic states adaptable by most cells | [26] |

| Colorectal Cancer | Lineage tracing in vivo | LGR5 | LGR5− cells regenerate LGR5+ CSCs following ablation | [30] |

| Breast Cancer | Basal-like subtype | ZEB1 | Non-stem cells spontaneously convert to stem-like state regulated by ZEB1 | [26] |

Methodological Framework for Studying Plasticity

Cell Sorting and Functional Validation

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) enables isolation of CSC and NSCC populations based on specific surface markers:

- Protocol: Cells are stained with fluorescently conjugated antibodies against CSC markers (e.g., CD133-APC, CD44-PE, CD24-Alex488) at concentrations of 10^7 cells per 100μl buffer. After incubation, cells are sorted using instruments such as BD FACS Aria II, with analysis on BD LSR II flow cytometers [27].

- Validation: Sorted populations must be functionally validated through sphere formation assays, in vivo limiting dilution transplantation, and Aldefluor assays to confirm stemness properties [5].

Lineage Tracing and Clonal Analysis

Genetic lineage tracing provides the most compelling evidence for plasticity by tracking the fate of individual cells and their progeny:

- Approach: Introduction of heritable genetic markers (e.g., Cre-recombinase systems, fluorescent reporters) under control of CSC-specific promoters (e.g., LGR5) enables visualization of lineage relationships over time [30].

- Application: In colorectal cancer models, this approach demonstrated that LGR5− cells can give rise to LGR5+ CSCs, confirming bidirectional interconversion [30].

Single-Cell Analysis and Mathematical Modeling

Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals transcriptional states along the epithelial-mesenchymal spectrum and identifies intermediate hybrid states [2] [29]. Mathematical modeling approaches, including ordinary differential equation (ODE)-based models and Boolean networks, help conceptualize the dynamics of CSC-NSCC interconversion and predict cellular behaviors under different conditions [29].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for CSC Plasticity. Process from tumor dissociation to functional validation demonstrates bidirectional conversion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for CSC Plasticity Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application/Function | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSC Surface Markers | Anti-CD133, Anti-CD44, Anti-CD24, Anti-ALDH1 | Identification and isolation of CSC populations | CD133 controversial in glioblastoma; ALDH1 activity via Aldefluor assay [4] |

| Signaling Inhibitors | SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor), DAPT (Notch inhibitor), Cyclopamine (Hedgehog inhibitor) | Perturb signaling pathways to test plasticity regulation | SB431542 significantly decreases CSC proportion in equilibrium models [27] |

| Cytokines/Growth Factors | Recombinant TGF-β1 | Induce EMT and promote stemness | 0.4 ng/ml TGF-β1 accelerates CSC-NSCC equilibrium [27] |

| Cell Tracking Dyes | Hoechst 33342, CFSE, Photo-convertible proteins | Lineage tracing and proliferation monitoring | Hoechst 33342 for DNA staining in microfluidic devices [27] |

| 3D Culture Matrices | Matrigel, Collagen, Organoid media | Maintain tumor architecture and niche interactions | Patient-derived organoids preserve cellular heterogeneity [30] |

| Drug Selection Agents | Cisplatin, 5-FU, Targeted inhibitors | Apply selective pressure to study plasticity in resistance | Low-dose platinum induces ABCG2 upregulation and CD133+ expansion [4] |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

The dynamic interconversion between CSCs and NSCCs represents a fundamental challenge in cancer therapeutics, as conventional treatments that eliminate rapidly dividing cells may enrich for CSCs through selective pressure and plasticity mechanisms [5] [4]. Several strategic approaches emerge from understanding this plasticity:

Targeting Plasticity Mechanisms

Rather than attempting to eliminate CSCs permanently—a challenging goal due to continuous repopulation from NSCCs—therapeutic efforts are shifting toward targeting the plasticity process itself. Potential strategies include:

- Locking cells in differentiated states: Forcing CSCs to adopt NSCC phenotypes without regenerative capacity [26].

- Preventing adaptive plasticity: Inhibiting molecular switches that enable transition to treatment-resistant states [28].

- Dual-targeting approaches: Simultaneously targeting both CSCs and NSCCs to prevent repopulation from either compartment [4].

Clinical Translation Challenges

The development of CSC plasticity-targeting therapies faces several obstacles:

- Toxicity concerns: Key plasticity pathways (Wnt, Notch, Hedgehog) play crucial roles in normal tissue homeostasis [5].

- Biomarker limitations: Current CSC markers insufficiently capture the dynamic nature of stemness states [25] [2].

- Microenvironmental influence: Niche-specific factors significantly modulate plasticity, creating context-dependent therapeutic responses [2] [30].

Future Research Directions

Advancing our ability to therapeutically target CSC plasticity requires:

- Improved model systems: Patient-derived organoids that better recapitulate tumor heterogeneity and microenvironmental interactions [30].

- Single-cell multi-omics: Integrated analysis of transcriptional, epigenetic, and protein expression to define plasticity trajectories [2].

- Mathematical modeling: Computational approaches to predict plasticity dynamics and treatment responses [29].

- Real-time monitoring: Advanced imaging and biosensor technologies to track plasticity events in living systems.

The plasticity paradigm underscores the remarkable adaptability of cancer cells and highlights the necessity for therapeutic strategies that account for dynamic cellular states rather than static cellular hierarchies. As our understanding of the molecular circuitry governing CSC-NSCC interconversion deepens, so too will our ability to develop interventions that target this fundamental driver of tumor resilience and therapeutic resistance.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) represent a dynamic subpopulation within tumors that drive intratumoral heterogeneity, therapeutic resistance, and disease recurrence. This technical review examines the genetic and epigenetic mechanisms through which CSCs generate and maintain heterogeneity, creating significant challenges for cancer therapy. CSCs exhibit remarkable plasticity, transitioning between functional states in response to therapeutic pressure and microenvironmental cues. Their capacity for self-renewal, differentiation, and adaptive resistance is governed by complex interactions between mutational processes, epigenetic reprogramming, and signaling pathway dysregulation. Understanding these mechanisms provides critical insights for developing CSC-targeted therapies to overcome treatment resistance. Emerging technologies in single-cell analysis, functional genomics, and computational biology are advancing our ability to dissect CSC heterogeneity and identify novel therapeutic vulnerabilities for precision medicine applications.

The cancer stem cell (CSC) paradigm has revolutionized our understanding of tumor biology, revealing that tumors are not uniform masses of identical cells but rather organized hierarchies with functional heterogeneity [1] [31]. CSCs sit at the apex of this hierarchy, possessing self-renewal capacity and the ability to differentiate into the diverse cell populations that constitute the tumor bulk [31]. This model explains critical clinical challenges including therapeutic resistance, metastasis, and relapse, as conventional therapies often eliminate rapidly dividing differentiated cancer cells while sparing the more quiescent CSCs [1] [32].

Intratumoral heterogeneity manifests both spatially (within different regions of the same tumor) and temporally (as tumors evolve over time and in response to treatment) [33] [34]. CSCs contribute to this heterogeneity through genetic instability, epigenetic plasticity, and dynamic interactions with the tumor microenvironment [1] [35]. The traditional view of CSCs as a fixed cellular entity has been replaced by a more nuanced understanding of stemness as a dynamic functional state that cancer cells can enter or exit based on intrinsic programs and extrinsic cues [25]. This plasticity enables tumors to adapt to therapeutic pressures and environmental challenges, making CSCs a moving target for treatment interventions.

This review examines the genetic and epigenetic mechanisms through which CSCs drive intratumoral heterogeneity, with implications for drug resistance and cancer progression. By synthesizing current research advances, we aim to provide a comprehensive framework for understanding CSC biology and its therapeutic implications.

Genetic Mechanisms of CSC-Driven Heterogeneity

CSCs contribute to genetic heterogeneity through multiple mechanisms that generate genomic diversity and enable evolutionary selection within tumor ecosystems. These mechanisms operate both in untreated tumors and under therapeutic pressure, leading to clonal expansion of resistant populations.

Genomic Instability and Mutational Diversity

CSCs exhibit elevated genomic instability, which serves as a fundamental source of genetic heterogeneity. Most tumors display some form of genomic instability, encompassing both solid malignancies and hematopoietic tumors [33]. This instability manifests through increased mutation rates and chromosomal segregation errors, which occur approximately once every 100 cell divisions [33] [34].

Therapy-induced mutations and severe genomic instability can accumulate, leading to a hypermutator phenotype that further increases intratumoral heterogeneity [34]. For example, temozolomide can induce a hypermutated phenotype by enriching transitional mutations in mismatch repair (MMR) genes [33]. This genomic plasticity enables CSCs to continuously generate diverse subclones with varying functional capabilities and drug sensitivities.

Extrachromosomal DNA and Clonal Evolution

Extrachromosomal DNA (eccDNA) represents another significant mechanism through which CSCs amplify genetic heterogeneity. These circular DNA elements exist outside chromosomes and can contain amplified oncogenes and drug resistance genes [33]. During tumor evolution, the asymmetric distribution of eccDNA to daughter cells results in tumor cell evolution and accumulated variation, producing different molecular and genetic characteristics from the primary cell [33] [34].

This process enables a form of "forced evolution" where CSCs rapidly generate diverse subclones in response to selective pressures. The genomic instability and distribution of eccDNA to offspring cells result in tumor cell evolution and accumulated variation, producing different molecular, genetic characteristics, and biological phenotypes from primary cells [33].

Table 1: Genetic Mechanisms Driving CSC-Mediated Heterogeneity

| Mechanism | Functional Consequence | Therapeutic Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic instability | Elevated mutation rates and chromosomal abnormalities | Increased adaptive potential and resistance evolution |

| Extrachromosomal DNA (eccDNA) | Amplification of oncogenes and resistance genes | Rapid generation of resistant subclones |

| Clonal evolution | Selection of fitter subpopulations under therapy | Treatment failure and disease progression |

| DNA repair dysregulation | Enhanced repair capacity in CSCs | Resistance to DNA-damaging therapies |

Spatial and Temporal Heterogeneity

Genetic heterogeneity manifests as both spatial and temporal diversity within tumors. Spatial heterogeneity refers to genetic differences between different regions of the same tumor or between primary tumors and metastases [33] [34]. For instance, in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), different regions of the same tumor may contain varying proportions of EGFR mutant and wild-type cells, with significant implications for response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors [33].

Temporal heterogeneity reflects the dynamic changes in tumor genetics over time and in response to therapeutic interventions [33] [34]. Successive biopsies to study tumor evolution suggest that chemotherapy can alter the tumor mutational spectrum and induce molecular changes over time [33]. Targeted therapies exert particularly strong selective pressure on cancer cells carrying oncogenes, leading to the emergence of resistance mutations [33].

Epigenetic Regulation of CSC Plasticity and Heterogeneity

Epigenetic mechanisms enable CSCs to dynamically alter their functional state without changes to their DNA sequence, creating non-genetic heterogeneity that contributes significantly to therapeutic resistance and adaptive potential.

Chromatin Remodeling and Cell State Transitions

The epigenetic landscape of CSCs governs their capacity for state transitions and phenotypic plasticity. Each cell state reflects a distinct configuration of gene regulatory networks (GRNs) that emerge from the complex interplay among chromatin structure, transcription factors, and gene expression [35]. The differential response of cancer cell states to treatment may be explained by variations in their chromatin architecture itself and the resulting activation of specific GRNs [35].

Histone modifications play a particularly significant role in tumor evolution processes [35]. For example, breast cancer cells can reach a drug-tolerant state by reducing H3K27me3 histone marks, while inhibition of H3K27me3 demethylation in combination with chemotherapy prevents the transition to this drug-tolerant state [35]. These epigenetic alterations create a reservoir of cell states that can be selected under therapeutic pressure.

Polycomb Complexes and Stemness Maintenance

Polycomb group complexes (PRC1 and PRC2) serve as critical regulators that bridge epigenetic control and stemness maintenance. Their synergistic activity leads to the formation of transcriptionally repressive Polycomb domains characterized by compacted chromatin enriched in H2AK119ub1 (catalyzed by PRC1) and H3K27me3 (catalyzed by PRC2) [35].

BMI1 (a component of PRC1) is associated with self-renewal capacity of various adult stem cells and plays a preponderant role in maintaining stemness in malignant cells [35]. Beyond its function in stemness regulation, BMI1 contributes to the DNA damage response by depositing H2AK119ub mark at DNA lesions, facilitating repair through homologous recombination [35]. This dual function connects stemness maintenance with DNA repair capacity, contributing to therapy resistance in CSCs.

Similarly, EZH2 (the catalytic component of PRC2) is frequently overexpressed in CSCs and regulates DNA repair through modulation of SLFN11 expression and inhibition of transcriptional activity at DNA damage sites [35]. The MELK-FOXM1-EZH2 signaling axis has been identified as essential for glioblastoma stem cell radioresistance [35].

Table 2: Epigenetic Regulators in CSC Maintenance and Heterogeneity

| Epigenetic Regulator | Function in CSCs | Role in Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|

| BMI1 (PRC1) | Self-renewal maintenance, DNA damage response | Promotes stem state stability and therapeutic resistance |

| EZH2 (PRC2) | Histone methylation, gene silencing | Maintains undifferentiated state, suppresses differentiation |

| BRD4 (BET protein) | Enhancer activity, transcriptional elongation | Regulates state transitions and phenotypic plasticity |

| DNA methylation enzymes | Promoter methylation, gene silencing | Stabilizes cellular states and restricts differentiation |

DNA Methylation and Cellular Identity

DNA methylation patterns contribute significantly to CSC identity and heterogeneity. Temporal shifts in DNA methylation patterns and DNA methylation in the transcription of genes represent key epigenetic mechanisms that influence cellular identity and functional states [33]. These methylation changes can create stable epigenetic states that persist across cell divisions, contributing to the maintenance of distinct cellular subpopulations within tumors.

Epigenetic modifications participate in tumor heterogeneity through their influence on drug-tolerant persister (DTP) cells and their role in increased tolerance to higher drug pressure [36]. Additionally, altering the epigenetic landscapes by DNA methylation aids in the maintenance and survival of CSCs which exhibit resistance features at the individual level [36].

Interplay Between DNA Damage Repair and Epigenetic Regulation

The relationship between DNA damage response and epigenetic regulation represents a critical interface that influences CSC behavior and contributes to intratumoral heterogeneity.

Cell Identity Influences DNA Damage Mapping

The epigenetic state of CSCs directly influences their pattern of DNA damage susceptibility. Genome-wide mapping of double-strand breaks (DSBs) demonstrates a relationship between genomic instability and nucleosome density [35]. DSBs are enriched in regions bearing epigenetic marks of transcriptionally active genes (H3K4me2/3), enhancer loci (H3K27ac, H3K9ac, and H3K4me1), and regions rich in structural proteins such as CTCF [35].

This mapping of genomic breaks or "breakome" is influenced by cell identity [35]. For example, glioblastoma CSCs exhibit high expression activity of genes located at common fragile sites compared to the glioblastoma cells composing the tumor bulk, leading to transcription-replication conflicts and increased DSB formation [35]. Thus, the specific transcriptional and epigenetic state of CSCs creates unique patterns of genomic vulnerability.

Epigenetic Regulation of DNA Repair Pathway Choice

Cell identity guides not only the distribution of DNA damage but also the choice of repair pathways. Beyond the traditional factors of damage type and cell cycle phase, the epigenetic state directly influences DNA damage response and repair capacity [35]. Dual-role regulators that maintain cell identity can activate specific DNA damage response pathways, creating a direct link between stemness and DNA repair.

As previously mentioned, BMI1 promotes DNA repair via homologous recombination through deposition of H2AK119ub at DNA lesions [35]. Similarly, BRD4 interacts with BRG1 and CtIP to facilitate homology-directed repair of DSBs [35]. These mechanisms enhance the DNA repair capacity of CSCs, contributing to their resistance to DNA-damaging therapies.

Diagram 1: Interplay between DNA damage repair and epigenetic regulation in CSCs. Epigenetic regulators including PRC1/BMI1, PRC2/EZH2, and BRD4 influence repair pathway choice through chromatin modifications, contributing to CSC therapeutic resistance.

CSC Signaling Pathways and Heterogeneity Maintenance

CSCs utilize evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways to maintain their stemness and generate cellular heterogeneity. These pathways respond to both intrinsic cues and signals from the tumor microenvironment.

Core Stemness Signaling Pathways

Three primary signaling pathways—Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog—play central roles in regulating CSC self-renewal and differentiation. These pathways, often dysregulated in cancer, represent a critical link to the tumorigenic potential of CSCs [31]. Targeting these self-renewal pathways offers promising therapeutic strategies to inhibit tumor proliferation and prevent recurrence.

In breast CSCs, specific signaling pathways including Notch, Wnt, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, TGF-β, and Hippo-YAP/TAZ regulate stemness maintenance and therapeutic resistance [32]. These pathways control processes such as drug escape and enhanced DNA repair that characterize CSC behavior [32]. The activity of these pathways varies across CSC subpopulations, contributing to functional heterogeneity.

Metabolic Plasticity and Heterogeneity

CSCs exhibit metabolic plasticity that enables their survival under diverse environmental conditions. Metabolic plasticity allows CSCs to switch between glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, and alternative fuel sources such as glutamine and fatty acids, enabling them to survive under diverse environmental conditions [1]. This metabolic flexibility contributes to functional heterogeneity and enables CSCs to adapt to nutrient deprivation, hypoxia, and therapeutic challenges.

Interactions with stromal cells, immune components, and vascular endothelial cells facilitate metabolic symbiosis, further promoting CSC survival and drug resistance [1]. The tumor microenvironment creates distinct metabolic niches that support different CSC states, adding another layer to intratumoral heterogeneity.

Diagram 2: Signaling pathways regulating CSC states and functional heterogeneity. Multiple signaling pathways integrate microenvironmental cues to generate diverse CSC states with distinct functional properties.

Methodologies for Investigating CSC Heterogeneity

Advanced experimental approaches are essential for dissecting the genetic and epigenetic complexity of CSCs and their contribution to intratumoral heterogeneity.

Single-Cell Analysis Technologies

Single-cell technologies have revolutionized our ability to characterize CSC heterogeneity. Recent advances in single-cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and multiomics integration have significantly improved our understanding of CSC heterogeneity and metabolic adaptability [1]. These approaches enable researchers to resolve the cellular diversity within tumors and identify rare CSC subpopulations that might be missed in bulk analyses.

Single-cell RNA sequencing and mutation characterization enable investigation of evolutionary dynamics in tumor cell populations, with important implications for individualized therapy [36]. These technologies can identify the cellular, molecular, and genetic processes that govern cancer cell plasticity [37].

Functional Screening Approaches

CRISPR-based functional screens provide powerful tools for identifying genetic and epigenetic dependencies in CSCs. The development of 3D organoid models, CRISPR-based functional screens, and AI-driven multiomics analysis is paving the way for precision-targeted CSC therapies [1]. These approaches enable systematic interrogation of gene function across diverse CSC states and genetic backgrounds.

Functional screens can identify vulnerabilities specific to CSCs versus more differentiated cancer cells, revealing potential therapeutic targets. Combining these screens with single-cell readouts further enhances resolution of cell-state-specific dependencies.

Table 3: Experimental Approaches for CSC Heterogeneity Research

| Methodology | Application | Key Insights |

|---|---|---|

| Single-cell RNA sequencing | Transcriptomic profiling of individual cells | Identification of rare CSC states and transition trajectories |

| CRISPR functional screens | Systematic gene function assessment | Discovery of CSC-specific genetic dependencies |

| Spatial transcriptomics | Gene expression in tissue context | Mapping CSC spatial distribution and niche interactions |

| Lineage tracing | Cell fate mapping | Understanding CSC differentiation hierarchies and plasticity |

| Organoid models | 3D culture of patient-derived cells | Preservation of tumor heterogeneity and drug response |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for CSC Heterogeneity Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| CSC surface markers | CD44, CD133, CD24, EpCAM | Isolation and purification of CSC subpopulations |

| Signaling pathway inhibitors | LGK974 (Wnt), DAPT (Notch), Vismodegib (Hedgehog) | Functional interrogation of stemness pathways |

| Epigenetic probes | GSK126 (EZH2 inhibitor), JQ1 (BET inhibitor) | Modulation of epigenetic states and plasticity |

| CSC functional assay kits | Mammosphere formation, ALDEFLUOR | Assessment of self-renewal and stemness properties |

| Lineage tracing systems | Cre-lox, barcoding technologies | Fate mapping and plasticity assessment |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

Understanding the genetic and epigenetic basis of CSC heterogeneity opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention to overcome treatment resistance.

Targeting CSC-Specific Vulnerabilities

Emerging therapeutic strategies aim to specifically target CSCs by exploiting their unique genetic and epigenetic dependencies. Emerging strategies such as dual metabolic inhibition, synthetic biology-based interventions, and immune-based approaches hold promise for overcoming CSC-mediated therapy resistance [1]. Moving forward, an integrative approach combining metabolic reprogramming, immunomodulation, and targeted inhibition of CSC vulnerabilities is essential for developing effective CSC-directed therapies [1].

Promising approaches include targeting the self-renewal pathways (Wnt, Notch, Hedgehog), epigenetic modifiers (EZH2, BET proteins), and immune evasion mechanisms employed by CSCs [1] [31]. Combination therapies that simultaneously target multiple vulnerabilities may be required to effectively eliminate CSCs and prevent resistance development.

Challenges in CSC-Targeted Therapy

Several significant challenges complicate the development of CSC-targeted therapies. Major hurdles remain, including the lack of universally reliable CSC biomarkers and the challenge of targeting CSCs without affecting normal stem cells [1]. The dynamic plasticity of CSCs enables them to adapt to therapeutic pressure by transitioning between states, creating a moving target for interventions [25] [37].

Tumor heterogeneity itself presents a barrier to effective treatment, as a single therapeutic agent may only be effective for subsets of cells with certain features, but not for others [33] [34]. This necessitates a shift from current treatment approaches to ones that are tailored against the killing patterns of cancer cells in different clones [33].

Future Research Directions

Future research should focus on deciphering the regulatory networks that control CSC state transitions and heterogeneity. Advanced technologies including artificial intelligence-driven analysis of multiomics data, improved organoid and tumor microenvironment models, and sophisticated lineage tracing approaches will be essential for mapping the complex dynamics of CSC populations [1] [31].

Integration of these approaches with clinical studies will enable validation of preclinical findings and facilitate translation to patient care. Additionally, developing strategies to manipulate CSC plasticity and differentiation states represents a promising avenue for neutralizing the threat posed by CSCs without necessarily eliminating them entirely.

CSCs drive intratumoral heterogeneity through complex genetic and epigenetic mechanisms that enable tumor adaptation, therapeutic resistance, and disease progression. Genetic instability generates diversity upon which selection can act, while epigenetic plasticity allows dynamic reprogramming of cellular states in response to environmental cues. The interplay between these mechanisms creates a complex ecosystem within tumors, with CSCs at its foundation.

Advancing our understanding of these processes requires sophisticated experimental approaches that can resolve heterogeneity at single-cell resolution and capture dynamic state transitions. Therapeutic progress will depend on developing strategies that account for and target this heterogeneity, potentially through combination approaches that address multiple vulnerabilities simultaneously. As research in this field advances, targeting CSC-driven heterogeneity holds promise for overcoming therapeutic resistance and improving cancer outcomes.

Advanced Techniques for Isolating, Validating, and Modeling CSCs

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) constitute a highly plastic and therapy-resistant cell subpopulation within tumors that drives tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and relapse [1]. Their ability to evade conventional treatments, adapt to metabolic stress, and interact with the tumor microenvironment makes them critical targets for innovative therapeutic strategies. A fundamental challenge in CSC research is their heterogeneity and the lack of universal biomarkers; for instance, glioblastoma (GBM) CSCs frequently express neural lineage markers like CD133, whereas gastrointestinal cancers may harbor CSCs characterized by LGR5 or CD166 expression [1]. Marker-based isolation via Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) provides a powerful method to isolate these rare CSCs from a heterogeneous tumor mass, enabling deeper study of their role in tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance [38] [39]. This guide details the core principles and protocols for using FACS to isolate CSCs, a critical step in understanding and ultimately overcoming therapeutic failure.

Core Principles of Flow Cytometry and FACS

Flow cytometry is an analytical technique that measures the physical and chemical properties of cells as they flow in a fluid stream past a laser beam [39]. FACS is a specialized form of flow cytometry that adds a cell sorting capability, allowing for the physical isolation of specific cell populations based on their measured characteristics [39].

Key System Components

The FACS system integrates several components to achieve this:

- Fluidics System: Utilizes sheath fluid and laminar flow to focus cells into a single-file stream, ensuring they pass through the laser interrogation point one at a time [39].

- Optical System: Includes lasers for illumination and lenses and filters to collect the resulting light signals. As cells pass through the laser, they scatter light. Fluorophores attached to antibodies on the cell emit light at specific wavelengths upon laser excitation [39].

- Electronics System: Photodetectors convert the scattered and fluorescent light signals into electronic signals. These are digitized and processed by computer software for analysis and decision-making [39].

- Sorting Mechanism: In FACS, the stream is broken into droplets. Based on the analyzed signals, an electrical charging ring applies a charge to droplets containing target cells. These charged droplets are then deflected by an electrostatic field into collection tubes [39].

Critical Parameters and Measurements

- Forward Scatter (FSC): Correlates with cell size; larger cells scatter more light in the forward direction [39].

- Side Scatter (SSC): Correlates with cellular granularity and internal complexity [39].

- Fluorescence Intensity: Measured by detectors for specific wavelengths, indicating the abundance of the target marker on the cell surface or inside the cell [39].

Table 1: Comparison of Flow Cytometry and FACS

| Aspect | Flow Cytometry | FACS |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Analytical technique for measuring cell properties | Specialized flow cytometry that sorts cells |

| Sorting Capability | Limited or absent | Ability to sort cells based on fluorescence |

| Primary Output | Multiparameter data for population analysis | Physically isolated cell populations |

| Instrument Complexity | Relatively simple | More complex due to sorting mechanisms |

FACS Workflow for CSC Isolation: A Detailed Protocol

The following protocol, adapted for CSC isolation, outlines the process from sample preparation to sorted cell collection.