Computational Tumor Models: Simulating Cancer Growth and Treatment Response for Precision Oncology

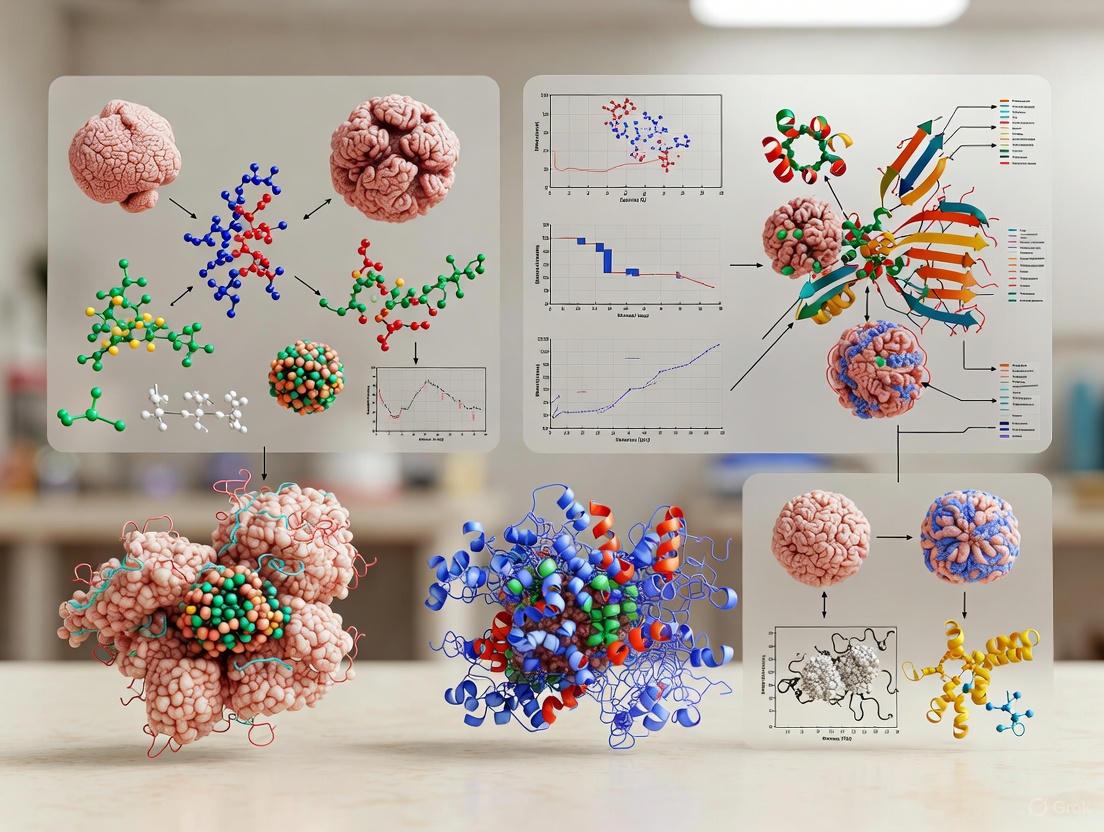

This article provides a comprehensive overview of computational models developed to simulate tumor growth and predict treatment response.

Computational Tumor Models: Simulating Cancer Growth and Treatment Response for Precision Oncology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of computational models developed to simulate tumor growth and predict treatment response. It explores the foundational principles of the tumor microenvironment and multiscale modeling, details key methodological frameworks like hybrid agent-based and PDE models, and examines their application in evaluating combination therapies and personalized treatment scheduling. The content further addresses critical challenges in model optimization and the rigorous validation processes required for clinical translation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current advances and future directions in computational oncology, highlighting its growing role in informing therapeutic strategies and advancing precision medicine.

Decoding the Tumor Microenvironment: The Biological Basis for Computational Modeling

The progression and treatment response of tumors are governed by interconnected biological hallmarks, with angiogenesis and metabolic reprogramming forming a particularly critical axis [1]. Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels, supplies essential nutrients and oxygen to growing tumors, while cancer cells simultaneously rewire their metabolic pathways to meet increased energy and biosynthetic demands [1]. This co-dependence creates a powerful engine for tumor growth and metastasis. In modern oncology research, computational models have become indispensable tools for simulating the complex, non-linear dynamics of this relationship, allowing researchers to predict tumor behavior and treatment outcomes in silico before moving to clinical trials [2] [3]. This application note details the key mechanisms, experimental protocols, and computational approaches for investigating this hallmark axis, providing a framework for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The interplay between angiogenesis and metabolism is primarily orchestrated by cellular sensing mechanisms that respond to the tumor's often hypoxic and nutrient-deficient microenvironment.

The Central Role of Hypoxia and HIF-1α

Hypoxia, a common feature of solid tumors, serves as a master regulator linking angiogenesis and metabolism. The key mediator is Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) [1] [4]. Under normal oxygen conditions, HIF-1α is rapidly degraded. However, in hypoxia, it stabilizes and translocates to the nucleus, where it dimerizes with HIF-1β and activates a transcriptional program that simultaneously promotes angiogenesis and glycolytic metabolism [4].

- Pro-angiogenic Shift: HIF-1α upregulates the expression of pro-angiogenic factors, most notably Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), which stimulates the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells to form new, often dysfunctional, blood vessels [1] [4].

- Metabolic Reprogramming: HIF-1α directly enhances glycolytic flux by increasing the expression of glucose transporters (e.g., GLUT1) and key glycolytic enzymes, including PFKFB3, PKM2, and LDHA. This shift to glycolysis, even in the presence of oxygen (the Warburg effect), provides rapidly dividing cells with ATP and biosynthetic precursors while reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [1].

The diagram below illustrates this core signaling pathway and its functional outcomes.

Key Metabolic Enzymes and Pathways in the Angiogenic Switch

The metabolic adaptations in endothelial and tumor cells are driven by specific enzymes and pathways. The table below summarizes the primary metabolic targets involved in this interplay.

Table 1: Key Metabolic Targets in Tumor Angiogenesis and Metabolic Reprogramming

| Target | Function | Role in Hallmarks | Therapeutic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFKFB3 [1] | Key regulator of glycolysis (controls fructose-2,6-bisphosphate levels). | Provides energy and biosynthetic precursors for endothelial cell proliferation and migration during angiogenesis. | Targeted inhibition suppresses vessel formation and tumor growth in models like infantile hemangioma. |

| Glycolytic Enzymes (PKM2, LDHA) [1] | Catalyze final steps of glycolysis and lactate production. | Supports the Warburg effect, generating ATP and reducing ROS under hypoxia. | Emerging target to disrupt energy production and acidify the microenvironment. |

| Fatty Acid Oxidation (FAO) Enzymes [5] | Oxidizes fatty acids in mitochondria for energy production. | A metabolic hallmark of pathological angiogenesis in proliferative retinopathies; supports EC proliferation. | Inhibition of CPT1a (shuttles fatty acids into mitochondria) reduces pathological tufts. |

| SIRT3 [5] | Mitochondrial deacetylase; master regulator of FAO and oxidative metabolism. | Modulates the balance between FAO and glycolysis in the vascular niche. | Sirt3 deletion shifts metabolism from FAO to glycolysis, promoting a more physiological vascular regeneration. |

Computational Modeling Protocols

Computational models provide a quantitative framework to simulate the spatiotemporal dynamics of tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metabolism, enabling the testing of therapeutic strategies in silico.

Protocol: Multi-Scale 3D Modeling of Tumor Growth and Angiogenesis

This protocol outlines the creation of a hybrid continuous-discrete model to simulate tumor progression and treatment response [2].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

Model Initialization and Domain Setup

- Spatial Domain: Define a 3D tissue region (e.g., 10x10x8 mm) [2].

- Initial Vasculature: Establish an idealized "mother vessel" from which angiogenic sprouts can initiate [2].

- Cancer Cell Population: Initialize a population of cancer cells with defined proliferation and migration parameters.

- Continuous Fields: Set up partial differential equations to model the spatiotemporal distribution of key factors:

- Nutrients/Oxygen (Diffusion, Consumption)

- VEGF (Secretion in hypoxia, Degradation)

- Therapeutic Agents (Transport, Clearance)

Simulation of Coupled Growth and Angiogenesis

- Vessel Sprouting: Model tip cell migration from existing vessels in response to VEGF gradients [2].

- Proliferation and Hypoxia: Cancer cells proliferate when nutrient levels are sufficient. Cells become hypoxic and may necrose when levels fall below a critical threshold, thereby upregulating VEGF secretion [2].

- Metabolic Modulation: Incorporate the influence of hypoxia (HIF-1α) on elevating glycolytic activity within both tumor and endothelial cells [1].

Introduction of Therapeutic Interventions

- Anti-angiogenic Therapy: Introduce an agent that blocks VEGF signaling, leading to vessel pruning or normalization [2].

- Cytotoxic Chemotherapy: Administer a cell-cycle active drug. Two scheduling paradigms can be tested:

- Metabolic Inhibitors: Introduce compounds that target key enzymes like PFKFB3 to disrupt the energy supply for angiogenesis [1].

Output Analysis

- Tumor Metrics: Total tumor volume, invasive distance, and degree of necrosis.

- Vascular Metrics: Vessel density, perfusion, permeability, and interstitial fluid pressure (IFP).

- Treatment Efficacy: Quantify tumor cell killing and drug penetration profiles.

Protocol: Virtual Clinical Trial for Treatment Optimization

This protocol leverages a stochastic mathematical model to simulate clinical trials and optimize maintenance treatment protocols [6].

Detailed Methodology:

Model Calibration

- Use data from a landmark clinical trial (e.g., the SOLO-1 trial for olaparib in ovarian cancer) to calibrate the model parameters [6].

- Key parameters to fit include: cancer cell proliferation and death rates, acquisition rates for drug resistance, pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters for the drug, and models for treatment-induced toxicity (e.g., white blood cell dynamics) [6].

Virtual Patient Population Generation

- Simulate a large cohort of virtual patients (e.g., N=10,000). Incorporate inter-patient heterogeneity by sampling key parameters (e.g., initial tumor burden, resistance mutation rates) from predefined distributions [6].

Trial Simulation and Intervention

- Simulate the standard-of-care treatment arm as a control.

- Design and simulate one or more experimental arms testing alternative protocols. Variables to test include [6]:

- Treatment Duration: Continuous vs. fixed-duration maintenance.

- Dosing Schedules: MTD vs. metronomic dosing, or adaptive dosing based on simulated toxicity.

- Combination Therapies: Sequencing of anti-angiogenic, cytotoxic, and metabolic drugs.

Endpoint Analysis

- Calculate primary endpoints such as Progression-Free Survival (PFS) and Overall Survival (OS) for each virtual arm using Kaplan-Meier estimators [6].

- Compare the hazard ratios between experimental and control arms to identify the most promising protocol for further clinical investigation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Investigating Angiogenesis and Metabolic Reproprogramming

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| siRNA/shRNA against PFKFB3 [1] | To knock down PFKFB3 expression in vitro (e.g., in hemangioma-derived endothelial cells) and in vivo, validating its role in glycolysis-driven angiogenesis. |

| Sirt3-Knockout Mouse Model [5] | An in vivo model to study the role of mitochondrial metabolism and the shift between FAO and glycolysis in pathological vs. physiological angiogenesis. |

| Oxygen-Induced Retinopathy (OIR) Mouse Model [5] | A well-established in vivo model for studying pathological angiogenesis and testing anti-angiogenic and metabolic therapies. |

| Anti-VEGF Therapeutics (e.g., Bevacizumab) [1] [2] | Used as a reference anti-angiogenic agent in both experimental and computational studies to benchmark novel therapies. |

| mTOR Inhibitor (Sirolimus/Rapamycin) [1] | A first-line treatment for borderline tumors like KHE; used to investigate the therapeutic inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway which suppresses angiogenesis and metabolic rewiring. |

| Metabolic Tracers (e.g., ²H-glucose, ¹³C-glutamine) | To quantitatively track nutrient uptake and metabolic flux in cultured cells or animal models, providing data for constraining computational models. |

Application in Therapeutic Development

Computational models have revealed several non-intuitive, promising therapeutic strategies that target the angiogenesis-metabolism axis.

Table 3: Emerging Therapeutic Strategies Informed by Computational Models

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Model-Predicted Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Metronomic Chemotherapy + Anti-angiogenics [2] | Frequent, low-dose cytotoxic drug combined with a vessel-normalizing anti-angiogenic agent. | Enhanced drug delivery via improved vessel function, reduced hypoxia, and decreased cancer cell invasion. Superior tumor killing and reduced normal tissue toxicity compared to MTD. |

| Targeting Endothelial Cell Metabolism [1] | Inhibition of glycolytic regulators (e.g., PFKFB3) in endothelial cells, rather than targeting angiogenic growth factors. | Effective suppression of angiogenesis regardless of compensatory upregulation of pro-angiogenic factors, potentially overcoming resistance to VEGF-targeted monotherapy. |

| Metabolic Reprogramming of the Neovascular Niche [5] | Shifting the vascular niche metabolism from FAO to glycolysis (e.g., via Sirt3 modulation). | Suppression of pathological neovessels and promotion of healthy, physiological revascularization, as demonstrated in models of proliferative retinopathy. |

| Adaptive Therapy [3] | Dynamically adjusting drug dosing and scheduling to maintain a population of therapy-sensitive cells that suppress the growth of resistant clones. | Delayed emergence of drug resistance and prolonged progression-free survival, moving beyond the Maximum Tolerated Dose paradigm. |

The Challenge of Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity in Solid Tumors

Spatiotemporal heterogeneity represents a fundamental challenge in the understanding and treatment of solid tumors. This complexity encompasses genetic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolic variations that evolve over both space and time within a single tumor mass [7] [8]. Intratumoral heterogeneity can be categorized into spatial heterogeneity (variations across distinct geographical regions of the tumor) and temporal heterogeneity (changes in the tumor's genetic and phenotypic profile over time) [7]. This dynamic variability is not random but is shaped by complex intra- and inter-cellular networks and microenvironmental pressures such as oxygen and nutrient gradients [7] [9].

The clinical significance of spatiotemporal heterogeneity cannot be overstated. It serves as a key driver of cancer progression, therapy resistance, and disease relapse [7] [9]. Different tumor sub-regions exhibit varied responses to therapeutic agents, allowing resistant clones to survive treatment and eventually repopulate the tumor. Understanding these dynamics is therefore crucial for developing targeted therapeutic strategies that can address tumor diversity and adaptability [7].

Key Dimensions of Tumor Heterogeneity

Molecular and Cellular Scales

Spatiotemporal heterogeneity operates across multiple biological scales, from molecular alterations to cellular ecosystem reorganization:

- Genetic Heterogeneity: Arises from accumulated somatic mutations and copy number alterations (CNAs) that vary between different tumor regions [7] [8]. Subclonal populations compete and evolve under selective pressures, including therapy.

- Metabolic Heterogeneity: Driven by microenvironmental gradients, tumors establish spatially structured metabolic networks where oxygen-rich regions may utilize oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) while hypoxic cores exhibit glycolytic dominance [9].

- Phenotypic Heterogeneity: Manifested through diverse cell states and differentiation programs within the tumor, including epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and stem-like properties that influence metastatic potential and therapy resistance [8].

Metabolic Heterogeneity Across Tumor Types

Table 1: Spatial Metabolic Characteristics Across Different Solid Tumors

| Tumor Type | Core Region Characteristics | Marginal Zone Characteristics | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glioblastoma | Enhanced glycolysis; hypoxia-induced HIF-1α [9] | Active OXPHOS; more aggressive phenotype [9] | Hypoxic regions are radioresistant; requires combination therapy [9] |

| Breast Cancer | High glucose content; glycolytic metabolism [9] | Preference for mitochondrial metabolism [9] | Combined PI3K and bromodomain inhibition can overcome resistance [9] |

| Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (PanNETs) | Homogeneous glycolysis (mTOR-VEGF axis dominance) [9] | Lactate shuttling to stromal fibroblasts [9] | mTOR inhibitors reduce glycolytic flux but may increase metastasis risk [9] |

| Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC) | Significant glycolytic activity; lactic acid production [9] | Immune/stromal cells uptake lactate for energy [9] | Targeting lactate metabolism (MCT inhibitors) may enhance immunotherapy [9] |

Computational Modeling Approaches

Computational models have emerged as indispensable tools for deciphering spatiotemporal heterogeneity, enabling researchers to simulate tumor growth, treatment response, and underlying biological mechanisms across multiple scales.

Multi-Scale Modeling Frameworks

Hybrid continuous-discrete models integrate continuum equations for diffusible factors (oxygen, nutrients, growth factors) with discrete agent-based representations of individual cells and blood vessels [2] [10] [11]. This approach naturally captures the evolution of spatial heterogeneity, a major determinant of nutrient and drug delivery [2]. These models can recapitulate the shift from avascular to vascular growth by simulating tumor-induced angiogenesis, where cancer cells secrete factors like VEGF that stimulate new blood vessel growth toward the tumor [10] [11].

Three-dimensional models further enhance biological relevance by incorporating realistic tissue geometry and interstitial pressure distributions that influence tumor morphology. Simulations suggest that tumors with high interstitial pressure are more likely to develop invasive dendritic structures compared to those with lower pressure [10].

Integration of Imaging and Omics Data

Modern computational approaches increasingly incorporate experimental data to improve predictive accuracy. Image-based modeling utilizes clinical imaging data (microCT, DCE-MRI, perfusion CT) to derive input parameters on tumor vasculature and morphology, enabling patient-specific simulations [11]. These imaging modalities can resolve microvascular structures and provide surrogate measures of tumor perfusion and vascular permeability [11].

Spatial multi-omics integration represents another frontier, with computational methods like Tumoroscope enabling the mapping of cancer clones across tumor tissues by integrating signals from H&E-stained images, bulk DNA sequencing, and spatially-resolved transcriptomics [12]. This probabilistic framework deconvolutes clonal proportions in each spatial transcriptomics spot, revealing spatial patterns of clone colocalization and mutual exclusion [12].

Machine Learning for Predictive Oncology

Machine learning (ML) applications in oncology include predicting treatment response and optimizing therapeutic strategies. Causal machine learning (CML) integrates ML algorithms with causal inference principles to estimate treatment effects from complex, high-dimensional real-world data (RWD) [13]. Unlike traditional ML focused on pattern recognition, CML aims to determine how interventions influence outcomes, distinguishing true cause-and-effect relationships from correlations [13].

ML models also show promise in functional precision medicine, where drug screening data from patient-derived cells are leveraged to predict individual treatment options. Recommender systems trained on historical drug response profiles can accurately rank drugs according to their predicted activity against new patient-derived cell lines [14].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Spatial Multi-Omics Integration for Clonal Deconvolution

Objective: To map cancer clones and their spatial distribution within tumor tissues by integrating histology, genomics, and transcriptomics data.

Materials and Reagents:

- Fresh frozen or FFPE tumor tissue sections

- H&E staining reagents

- Spatial transcriptomics platform (e.g., 10x Genomics Visium, NanoString CosMx)

- Whole exome sequencing kit

- DNA and RNA extraction kits

Procedure:

- Tissue Processing and Staining

- Section tumor tissue at appropriate thickness (5-10 μm) and mount on spatial transcriptomics slides.

- Perform H&E staining according to standard protocols.

- Image stained slides using high-resolution slide scanner.

Cell Counting and Spot Annotation

- Use image analysis software (e.g., QuPath) to identify spatial transcriptomics spots located within cancer cell regions.

- Estimate the number of cells present in each spot based on nuclear density and morphology.

DNA and RNA Extraction

- Isolve DNA from adjacent tissue sections or macro-dissected regions for bulk whole exome sequencing.

- Process spatial transcriptomics slides according to platform-specific protocols to capture spatially barcoded RNA.

Sequencing and Data Generation

- Perform whole exome sequencing to identify somatic mutations and copy number alterations.

- Sequence spatial transcriptomics libraries to obtain gene expression data with spatial coordinates.

Computational Analysis

- Reconstruct cancer clones, including their genotypes and frequencies, from bulk DNA-seq data using tools like FalconX or Canopy.

- Apply Tumoroscope probabilistic model to deconvolute clonal proportions in each spot using:

- Prior cell counts from H&E analysis

- Alternative and total read counts for mutations in ST spots

- Clone genotypes and frequencies from bulk sequencing

- Infer clone-specific gene expression profiles using regression modeling.

Validation: Assess model performance using simulated data with known ground truth, calculating Mean Average Error (MAE) between inferred and true clone proportions across spots [12].

Protocol 2: Computational Simulation of Tumor Growth and Treatment Response

Objective: To simulate three-dimensional tumor growth, angiogenesis, and response to different therapy schedules using a multiscale mathematical model.

Materials and Software:

- High-performance computing environment

- Programming languages (Java, Python, C++)

- MicroCT or other medical imaging data (optional)

- Parameter values from literature for tumor biology

Procedure:

- Model Initialization

- Define 3D simulation domain representing a tissue region (e.g., 10×10×8 mm).

- Initialize tumor cell population at domain center with random phenotypes.

- Establish initial vascular network, either idealized or derived from imaging data.

Parameter Setting

- Configure parameters for nutrient (oxygen, glucose) diffusion and consumption rates.

- Set production and degradation rates for signaling molecules (VEGF, angiopoietins).

- Define drug pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters for simulated therapies.

Simulation Execution

- Employ hybrid modeling approach:

- Continuum equations for diffusible factors (oxygen, VEGF, drugs)

- Agent-based representation for individual cells and vessels

- Calculate spatial concentration gradients at each time step.

- Update cell states (proliferation, quiescence, death) based on local microenvironment.

- Simulate angiogenic sprouting guided by VEGF gradients.

- Employ hybrid modeling approach:

Treatment Simulation

- Implement different dosing schedules (MTD vs. metronomic).

- Simulate combination therapies (cytotoxic + anti-angiogenic).

- Track drug distribution through vascular network and tissue penetration.

Output Analysis

- Quantify tumor growth kinetics and morphological changes.

- Analyze spatial distribution of viable, hypoxic, and necrotic regions.

- Evaluate treatment efficacy based on tumor cell killing and normal tissue toxicity.

Validation: Compare simulation predictions with experimental data from preclinical models, including tumor growth curves and histological analysis [2] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for Studying Tumor Heterogeneity

| Category | Specific Tool/Platform | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Transcriptomics | 10x Genomics Visium [7] | Genome-wide expression profiling with spatial context; spot diameter 55μm with Visium HD down to 2μm. |

| NanoString CosMx SMI [7] | Spatial multi-omics at single-cell/subcellular resolution; quantifies up to 6000 RNAs and 64 proteins. | |

| BGI Stereo-seq [7] | Large-area spatial transcriptomics with high resolution. | |

| Single-Cell Analysis | scRNA-seq [9] [8] | Resolution of cell-to-cell variability in transcriptomes, revealing metabolic zonation and phenotypic heterogeneity. |

| Metabolic Imaging | Single-cell metabolomics [9] | Identification of therapy-resistant, fatty acid oxidation-dependent clones coexisting with glycolytic populations. |

| Computational Tools | Tumoroscope [12] | Probabilistic model integrating histology, bulk DNA-seq, and spatial transcriptomics to map clonal distributions. |

| PASTE/GraphST [7] | Computational alignment and integration of multi-slice spatial transcriptomics data for 3D tissue reconstruction. | |

| Multiscale hybrid models [2] [10] | Simulation of tumor growth, angiogenesis, and treatment response by combining continuum and agent-based approaches. |

Therapeutic Implications and Intervention Strategies

Targeting Metabolic Vulnerabilities

The spatial organization of tumor metabolism presents therapeutic opportunities. Strategies include:

- Inhibiting metabolic symbiosis through monocarboxylate transporters (MCT1/MCT4) blockade to disrupt lactate shuttling between hypoxic and oxygenated regions [9].

- Combination therapies that simultaneously target glycolytic and oxidative populations, such as combining glycolysis inhibitors (2-deoxyglucose) with OXPHOS inhibitors [9].

- Context-specific targeting of metabolic adaptations; for instance, PRODH inhibitors can sensitize hypoxic osteosarcoma cores to therapy [9].

Optimizing Treatment Scheduling and Delivery

Computational modeling provides insights for improving therapeutic efficacy:

- Metronomic scheduling of chemotherapy (frequent, low doses) improves drug delivery by normalizing tumor vasculature, reducing interstitial fluid pressure, and decreasing cancer cell invasion compared to maximum tolerated dose (MTD) regimens [2].

- Anti-angiogenic combinations can enhance metronomic therapy by further promoting vascular normalization, improving tumor perfusion, and reducing drug accumulation in normal tissues [2].

- Spatiotemporally informed dosing accounts for heterogeneous drug distribution within tumors, potentially targeting specific subclones based on their spatial location and microenvironment [2].

Functional Precision Medicine Approaches

Machine learning-driven strategies using patient-derived models offer complementary approaches to genomics-based precision medicine:

- Bioactivity fingerprinting uses historical drug screening data against patient-derived cell lines to predict effective treatments for new patients through recommender systems [14].

- Real-world data integration with causal machine learning enables identification of patient subgroups with distinct treatment responses and optimization of dosing strategies based on heterogeneous outcomes [13].

Spatiotemporal heterogeneity in solid tumors represents a multifaceted challenge that necessitates equally sophisticated research approaches. The integration of spatial multi-omics technologies, multiscale computational modeling, and machine learning analytics provides a powerful framework for dissecting this complexity. These approaches reveal not just the static structure of tumors but their dynamic evolution under therapeutic pressure.

The future of oncology research and treatment lies in embracing this complexity through spatiotemporally informed therapeutic strategies that account for intra-tumoral variation and adaptability. By targeting multiple subclones and microenvironmental niches simultaneously, and by optimizing drug scheduling based on tumor dynamics, we can develop more durable and effective treatments. The continued refinement of computational models, coupled with validation in patient-derived systems and clinical trials, will be essential for translating our understanding of heterogeneity into improved patient outcomes.

Cancer is a systems-level disease characterized by uncontrolled cell growth and tissue invasion, with dynamics that span multiple biological scales in space and time [15]. Multiscale computational modeling has emerged as a powerful approach to simulate cancer behavior across these different scales, providing quantitative insights into tumor initiation, progression, and treatment response [15] [16]. These models mechanically link processes from the intracellular level to tissue-scale phenomena, enabling researchers to test hypotheses, focus experimental efforts, and make more accurate predictions about clinical outcomes [15].

The fundamental challenge addressed by multiscale modeling is that tumors are heterogeneous cellular entities whose growth depends on dynamic interactions among cancer cells themselves and with their constantly changing microenvironment [15]. These interactions include signaling through cell adhesion molecules, differential responses to growth factors, and phenotypic behaviors such as proliferation, apoptosis, and migration [15]. Since experimental complexity often restricts the spatial and temporal scales accessible to observation, computational modeling provides an essential tool for investigating these dynamic interactions [15].

Biological Scales in Cancer Modeling

Multiscale cancer modeling typically addresses four principal spatial scales, each with associated temporal scales and specialized modeling techniques [15]. The table below summarizes these scales and their corresponding modeling approaches.

Table 1: Biological Scales in Multiscale Cancer Modeling

| Spatial Scale | Spatial Range | Temporal Range | Key Biological Processes | Common Modeling Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic | nm | ns | Protein structure, ligand binding, molecular dynamics | Molecular Dynamics (MD) |

| Molecular | nm - μm | μs - s | Cell signaling pathways, biochemical reactions | Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) |

| Microscopic (Cellular/Tissue) | μm - mm | min - hour | Cell-cell interactions, proliferation, apoptosis, migration | Agent-Based Models (ABM), Cellular Potts Models (CPM), Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) |

| Macroscopic | mm - cm | day - year | Gross tumor morphology, vascularization, invasion | Continuum models, PDEs |

These scales are not independent but interact bidirectionally, with lower-level processes (e.g., molecular signaling) influencing higher-level behaviors (e.g., tissue growth) and vice versa [15]. A key principle in multiscale modeling is that lower-level processes generally occur on faster time scales than higher-level processes, which sometimes allows modelers to assume quasi-equilibrium for faster processes to reduce computational complexity [15].

Computational Frameworks and Techniques

Modeling Paradigms

Multiscale cancer models employ diverse computational approaches, each suited to different aspects of the biological system:

Continuum Models: Based on differential equations that describe average properties of cell populations and chemical concentrations across tissue space [15] [17]. These typically use advection-diffusion-reaction equations to model nutrient transport, growth factor diffusion, and tissue mechanics [18].

Discrete Models: Treat individual cells as distinct entities with specific rules governing their behavior [17]. These include:

Hybrid Models: Combine continuum and discrete approaches to leverage the strengths of both frameworks [15] [17] [16]. For example, a hybrid model might use discrete agent-based modeling for individual cells while representing diffusible chemicals and tissue mechanics with continuum equations [17] [19].

A Fully Coupled Multiscale Framework

Advanced multiscale frameworks fully couple processes across tissue, cellular, and subcellular scales [18]. In such frameworks:

- The tissue scale uses continuum mixture theory to model overall tumor growth, morphology, nutrient diffusion, and growth-induced mechanical stresses [18].

- The cellular scale employs agent-based modeling to simulate cell division, apoptosis, and phenotypic transitions based on local microenvironmental conditions [18].

- The subcellular scale implements ordinary differential equations to represent key signaling pathways (e.g., mTOR pathway) that regulate cellular behaviors [18].

These scales are bidirectionally coupled, with information flowing from tissue scale to cellular fate decisions and from cellular behaviors back to tissue properties, while signaling pathways regulate both directions based on molecular cues [18].

Diagram 1: Information flow in a fully coupled multiscale modeling framework

Protocols for Multiscale Model Development

Protocol 1: Building a Hybrid Model of Tumor Growth and Angiogenesis

This protocol outlines the development of a multiscale model that simulates tumor growth from avascular to vascular phases, incorporating tumor-host interactions and angiogenesis [17] [19].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Multiscale Modeling

| Component | Type | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boolean Network Model | Intracellular Scale | Describes receptor cross-talk and signaling pathway activation | Represents interactions between oncogenes and tumor suppressors [17] |

| Cellular Potts Model (CPM) | Cellular Scale | Captures cell shape changes, mechanical interactions | Simulates cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions [17] [19] |

| Reaction-Diffusion Equations | Tissue Scale | Models nutrient and growth factor transport | PDEs for oxygen, glucose, VEGF diffusion [17] [18] |

| Continuum Mixture Theory | Tissue Scale | Represents mechanical behavior of growing tissue | Multi-constituent mixture (tumor cells, healthy cells, ECM, nutrients) [18] |

| Agent-Based Framework | Cellular Scale | Controls individual cell decisions and phenotypes | Rules for cell division, migration, death based on local environment [18] [11] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Define the Intracellular Signaling Network

Implement Cellular Scale Interactions

- Configure a Cellular Potts Model to simulate mechanical interactions between cancer cells, healthy cells, and extracellular matrix [17] [19]

- Establish rules for phenotype transitions (proliferation, quiescence, apoptosis) based on intracellular signaling status and local microenvironment [17] [18]

- Define cell behavioral algorithms that respond to nutrient availability and mechanical stresses [17]

Set Up Tissue Scale Microenvironment

Implement Angiogenesis Module

Couple Scales and Validate Model

Protocol 2: Integrating Imaging Data with Predictive Growth Models

This protocol describes how to incorporate medical imaging data to initialize and constrain multiscale models for personalized prediction of tumor growth [11].

Materials and Specialized Software

- High-resolution medical images (microCT, DCE-MRI, perfusion CT)

- Image segmentation software for tumor and vasculature delineation

- Computational framework for agent-based modeling with reinforcement learning

- Neural network architecture for phenotype prediction

Step-by-Step Procedure

Image Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Acquire longitudinal microCT or other high-resolution images with contrast enhancement for vascular visualization [11]

- Segment tumor region and microvascular network from images at multiple time points [11]

- Extract quantitative features including vascular density, branching patterns, and tumor morphology [11]

Model Initialization from Image Data

Implement Reinforcement Learning for Cell Behavior

Simulate Tumor and Vascular Co-evolution

Validate and Refine Predictions

Signaling Pathways in Multiscale Cancer Models

Key signaling pathways regulate cellular decisions within multiscale models, translating microenvironmental conditions into phenotypic responses. The mTOR pathway is frequently incorporated due to its central role in controlling cell growth and proliferation in response to nutrient availability and growth factors [18]. In multiscale frameworks, this pathway is typically modeled using ordinary differential equations that track concentrations of pathway components over time [18].

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1) signaling serves as a critical link between tumor metabolism and angiogenesis [17] [19]. Under hypoxic conditions, HIF-1 accumulation upregulates VEGF expression, initiating the angiogenic switch that transitions tumors from avascular to vascular growth phases [17] [19]. This pathway creates a crucial feedback loop between tissue-scale oxygen distribution and molecular-scale signaling events.

Diagram 2: Key signaling pathways implemented in multiscale cancer models

Applications in Treatment Response Prediction

Multiscale models have significant applications in predicting responses to cancer therapies and optimizing treatment strategies [20] [18]. By incorporating drug mechanisms across biological scales, these models can simulate how targeted therapies alter system dynamics and ultimately affect tumor progression.

Modeling Targeted Therapies

In multiscale frameworks, targeted therapies are implemented as perturbations to specific signaling pathways at the subcellular scale [18]. For example, mTOR inhibitors (e.g., rapamycin) can be modeled by modifying the ordinary differential equations that describe mTOR pathway dynamics [18]. The downstream effects of these perturbations then propagate upward through the modeling framework, altering cellular phenotypic decisions and ultimately modifying tissue-scale tumor growth patterns [18].

Simulation studies have demonstrated that therapy blocking relevant signaling pathways can prevent further tumor growth and lead to substantial decreases in tumor size (up to 82% reduction in simulated tumors) [17]. These treatment effects emerge naturally from the coupled multiscale dynamics rather than being imposed as empirical rules.

Integrating Machine Learning for Personalized Prediction

Machine learning approaches are increasingly being integrated with multiscale modeling to predict individual patient treatment responses [14]. These methods leverage high-throughput drug screening data from patient-derived cell cultures to build predictive models of drug sensitivity [14]. The resulting "recommender systems" can efficiently rank potential treatments based on their predicted activity against a patient's specific cancer cells [14].

Table 3: Machine Learning Approaches for Treatment Prediction

| Method | Application | Performance Metrics | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformational Machine Learning (TML) | Predicting drug responses in patient-derived cell lines | Rpearson = 0.781, Rspearman = 0.791 for selective drugs [14] | Leverages historical screening data as descriptors for new predictions |

| Random Forest | Drug activity prediction | 50 trees with default parameters [14] | Handles complex interactions between multiple drugs and cell types |

| Deep Reinforcement Learning | Cell phenotype prediction in tumor microenvironment | Adapts based on reward functions aligned with experimental data [11] | Enables adaptive cell decisions based on local microenvironment |

Multiscale computational modeling provides a powerful framework for bridging molecular, cellular, and tissue levels in cancer research. By integrating processes across spatial and temporal scales, these models offer mechanistic insights into tumor growth dynamics and treatment responses that cannot be achieved through single-scale approaches alone. The protocols outlined in this document provide practical guidance for implementing multiscale models that combine continuum, discrete, and intracellular modeling techniques. As these approaches continue to evolve and incorporate emerging data sources—from high-resolution medical imaging to high-throughput drug screening—they hold increasing promise for guiding personalized cancer treatment strategies and accelerating therapeutic development.

The Role of the Tumor Microenvironment (TME) in Treatment Failure

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a dynamic and complex ecosystem that plays a critical role in cancer progression and therapeutic failure. Rather than being a passive surrounding, the TME actively engages in intricate crosstalk with cancer cells, fostering an environment conducive to immune evasion, metabolic adaptation, and drug resistance [21] [22]. This application note examines the core mechanisms by which the TME contributes to treatment failure, framed within the context of developing predictive computational models for oncology research and drug development. Understanding these interactions is paramount for designing next-generation therapies that can effectively overcome the barriers posed by the TME.

Key Mechanisms of TME-Mediated Treatment Failure

The TME drives treatment failure through several interconnected biological programs. The major mechanisms and their cellular effectors are summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Core Mechanisms of TME-Mediated Treatment Failure and Key Cellular Effectors

| Mechanism | Key Components | Impact on Treatment Efficacy |

|---|---|---|

| Immunosuppression | Tregs, MDSCs, M2 Macrophages, PD-1/PD-L1 | Inhibits cytotoxic T-cell function, enables immune evasion [22] [23]. |

| Abnormal Vasculature | Endothelial cells, VEGF, HIF-1α | Impedes drug delivery, creates hypoxia, hinders T-cell infiltration [23]. |

| Metabolic Dysregulation | Lactate, HIF-1α, Aerobic Glycolysis (Warburg Effect) | Creates acidic conditions that suppress immune cell function [22] [23]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Remodeling | CAFs, Collagen, Fibronectin, Integrins | Creates physical barrier to drug penetration and immune cell migration [23]. |

| Cellular Crosstalk | Exosomes, Cytokines (e.g., TGF-β, IL-10) | Transfers resistance traits, reprograms surrounding cells to be pro-tumorigenic [21] [22]. |

The Immunosuppressive Niche

A primary mechanism of treatment failure, particularly for immunotherapies, is the establishment of an immunosuppressive niche within the TME. Key cellular players include:

- Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs): These cells expand in the TME and potently suppress the activity of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, which are crucial for anti-tumor immunity [22] [23].

- Regulatory T Cells (Tregs): Tregs inhibit the activation and effector functions of anti-tumor T cells, contributing to immune tolerance [23].

- Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs), particularly the M2 phenotype, promote tumor growth, tissue remodeling, and suppress adaptive immunity [22]. The expression of immune checkpoint molecules like PD-1/PD-L1 further inactivates T cells, making checkpoint inhibitors a critical therapeutic strategy [22] [23].

Dysregulated Angiogenesis and Hypoxia

Rapid tumor growth leads to an inadequate and dysfunctional vascular network [23]. This abnormal vasculature is leaky and disorganized, resulting in:

- Hypoxia: Poor perfusion creates regions of low oxygen, which stabilizes Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α (HIF-1α) [22] [23].

- HIF-1α acts as a master regulator, driving the expression of genes that promote angiogenesis, metastasis, and metabolic reprogramming toward glycolysis [23].

- Impaired Drug Delivery: The chaotic blood flow and high interstitial pressure hinder the uniform distribution and penetration of therapeutic agents into the tumor core, protecting cancer cells from exposure to drugs [23].

Metabolic Competition and Acidosis

Cancer cells undergo metabolic rewiring, preferentially using glycolysis for energy production even in the presence of oxygen (the Warburg effect) [23]. This has major consequences for the TME:

- Acidosis: Glycolysis leads to the overproduction and accumulation of lactic acid, lowering the extracellular pH to as low as 6.7 [23].

- Immune Suppression: An acidic environment directly impairs the function and cytotoxicity of T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, while promoting the polarization of macrophages toward the immunosuppressive M2 phenotype [22] [23]. This metabolic coupling between tumor and immune cells is a key mediator of immune escape.

The Fibrotic Barrier and ECM Remodeling

Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) are a dominant stromal cell type that become activated in the TME. They deposit and remodel the extracellular matrix (ECM), leading to:

- Increased Stiffness: A dense and fibrotic ECM creates a physical barrier that physically impedes the penetration of both immune cells and drugs [21] [23].

- Survival Signaling: ECM components like collagen and fibronectin engage with integrins on cancer cells, activating pro-survival signaling pathways such as FAK and PI3K that confer resistance to chemotherapy and targeted therapies [23].

Diagram 1: A simplified overview of how major TME components drive the key functional failures of therapy. The interconnected nature of these mechanisms often leads to synergistic resistance.

Quantitative Insights and Computational Modeling

Mathematical modeling provides a powerful framework to quantify the dynamics of the TME and predict its impact on therapeutic outcomes. The following table summarizes key parameters from a study modeling pancreatic cancer response to combination therapy.

Table 2: Key Parameters from a Mathematical Model of Pancreatic Tumor Growth and Treatment Response [24]

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Estimated Value/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Volume | ( N(t) ) | Tumor volume at time ( t ) | Dependent variable |

| Proliferation Rate | ( r ) | Intrinsic growth rate of tumor cells | Mouse-specific, estimated from data |

| Carrying Capacity | ( K ) | Maximum sustainable tumor size | Fixed from control group (median: ~1500 mm³) |

| Initial Condition | ( N_0 ) | Initial tumor volume at model start | Mouse-specific, estimated from data |

| Treatment Effect | ( \alpha ) | Death rate induced by therapy | Estimated for each treatment protocol |

| Effect Decay Rate | ( \beta ) | Rate at which treatment effect diminishes over time | Key for modeling sustained vs. transient response |

The study employed a hierarchical Bayesian framework to fit ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to longitudinal tumor volume data from a genetically engineered mouse model of pancreatic cancer (( Kras^{LSL-G12D}; Trp53^{LSL-R172H}; Pdx1-Cre )) treated with chemotherapy (NGC regimen: mNab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, cisplatin), stromal-targeting drugs (calcipotriol, losartan), and immunotherapy (anti-PD-L1) [24].

The core logistic growth model with treatment effect was formulated as: [ \frac{dN}{dt}=rN\left(1-\frac{N}{K}\right)-N\sum{i = 1}^{n}{\alpha}{i}{e}^{-\beta (t-{\tau}{i})}H(t-{\tau}{i}) ] where ( H(t-{\tau}{i}) ) is the Heaviside step function, and ( {\tau}{i} ) represents the time of the ( i )-th treatment dose [24]. This model successfully reproduced tumor growth dynamics across all scenarios with an average concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) of 0.99 ± 0.01 and demonstrated robust predictive ability in leave-one-out and mouse-specific predictions (average CCC > 0.74) [24]. This highlights the utility of such models in predicting tumor response and identifying responders versus non-responders.

Diagram 2: A generalized workflow for building and applying computational models to simulate tumor growth and treatment response within the complex TME, based on the methodology of [24].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating the TME

Objective: To model pancreatic tumor dynamics and response to combination therapies targeting both cancer cells and the TME.

Materials:

- Animal Model: Genetically engineered ( Kras^{LSL-G12D}; Trp53^{LSL-R172H}; Pdx1-Cre ) (KPC) mice for spontaneous pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC).

- Therapeutics:

- Chemotherapy: NGC combination (mNab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, cisplatin).

- Stromal-Targeting: Calcipotriol and Losartan.

- Immunotherapy: Anti-PD-L1 antibody.

- Equipment: Calipers or imaging system (e.g., ultrasound) for tumor volume measurement.

Procedure:

- Group Allocation: Randomize tumor-bearing mice into experimental groups (e.g., control, chemotherapy alone, chemotherapy + stromal-targeting, chemotherapy + immunotherapy).

- Treatment Administration: Initiate therapy when tumors reach a predefined volume (e.g., 100-150 mm³). Administer drugs according to their respective schedules (e.g., intraperitoneal injections for chemotherapeutics).

- Longitudinal Monitoring: Measure tumor dimensions using calipers at least 3 times over a 14-day period. Calculate tumor volume using the formula: ( V = \frac{1}{2} \times \text{length} \times \text{width}^2 ).

- Data Recording: Record individual tumor volumes for each mouse at each time point.

- Model Fitting: Use the recorded tumor volume data to estimate parameters (( r, K, N_0, \alpha, \beta )) of the ODE model (Eq. 1) using Bayesian inference or nonlinear regression techniques.

- Validation: Validate the model's predictive power using cross-validation techniques like leave-one-out or mouse-specific predictions.

Protocol 2: Analyzing Key TME Components via Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Objective: To quantify the density and spatial distribution of key cellular components of the TME in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissues.

Materials:

- Tissue Samples: FFPE tumor tissue sections from control and treated mice (from Protocol 1).

- Primary Antibodies: Antibodies against CAFs (α-SMA), T cells (CD3, CD8), Tregs (FoxP3), macrophages (CD68, iNOS for M1, CD206 for M2), endothelial cells (CD31).

- Detection System: HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and DAB chromogen.

- Equipment: Brightfield microscope coupled with a slide scanner and image analysis software.

Procedure:

- Sectioning: Cut FFPE blocks into 4-5 µm thick sections and mount on slides.

- Deparaffinization and Antigen Retrieval: Bake slides, deparaffinize in xylene, and rehydrate through a graded ethanol series. Perform heat-induced epitope retrieval in appropriate buffer (e.g., citrate, EDTA).

- Immunostaining:

- Block endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% H₂O₂.

- Block nonspecific binding with a serum-free protein block.

- Incubate with primary antibody overnight at 4°C.

- Incubate with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Develop with DAB chromogen and counterstain with hematoxylin.

- Image Acquisition and Analysis: Scan stained slides. Use image analysis software to quantify the number of positive cells per mm² or the percentage of positive area (for α-SMA) in multiple representative fields of view.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Models for TME and Treatment Resistance Research

| Item | Function/Description | Application in TME Research |

|---|---|---|

| KPC Mouse Model (( Kras^{LSL-G12D}; Trp53^{LSL-R172H}; Pdx1-Cre )) | A genetically engineered model that recapitulates key features of human pancreatic cancer, including a dense, immunosuppressive TME [24]. | In vivo studies of tumor-stroma interactions, drug delivery barriers, and testing TME-modifying therapies. |

| Anti-PD-L1 Antibody | Immune checkpoint inhibitor that blocks the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction, reversing T-cell exhaustion [24] [23]. | Studying immune evasion and evaluating combinatorial immunotherapy regimens. |

| Stromal-Targeting Agents (e.g., Losartan, Calcipotriol) | Drugs aimed at modulating the tumor stroma to reduce fibrosis and improve drug delivery [24]. | Investigating methods to disrupt the fibrotic barrier and sensitize tumors to chemotherapy. |

| CAF Marker: α-SMA Antibody | Primary antibody for identifying activated Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in tissue sections via IHC. | Quantifying stromal density and CAF activation status in response to therapy. |

| Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) & 3D Tumor Models | Ex vivo systems that preserve the cellular heterogeneity and some TME interactions of the original tumor [21]. | High-throughput drug screening and studying patient-specific mechanisms of resistance in a more physiologically relevant context. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms | Technology that allows mapping of gene expression data onto tissue architecture, preserving spatial context [21]. | Unraveling the spatial relationships and communication networks between different cell types within the TME. |

Modern oncology research is increasingly defined by a powerful synergy between computational modeling and experimental biology. This integrated approach enables researchers to transcend the limitations of purely observational studies, offering a dynamic, quantitative framework to understand cancer's inherent complexity. Computational models provide a structured platform to simulate tumor growth, treatment response, and disease progression, generating testable hypotheses that guide focused experimental validation. This cycle of in silico prediction and in vitro or in vivo verification accelerates the discovery of fundamental biological mechanisms and the development of more effective therapeutic strategies [25]. By bridging biological scales—from molecular pathways to whole-tumor dynamics—and managing the profound heterogeneity of cancer, these combined methodologies are paving the way for truly predictive oncology and personalized medicine.

The Multiscale Computational Toolkit for Oncology

A diverse set of computational frameworks has been developed to address the multifaceted nature of cancer biology. Each type of model offers unique strengths, making it suitable for investigating specific aspects of tumor development and treatment.

Table 1: Key Computational Modeling Frameworks in Oncology

| Model Type | Core Principle | Oncology Application Example | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanistic Models | Simulate disease processes based on established biological principles [25]. | Modeling cell-cycle dynamics to explore therapeutic resistance mechanisms [25]. | Provides a predictive framework grounded in biological plausibility. |

| Agent-Based Models | Represent individual cells (agents) and their interaction rules [25]. | Studying cell-cell interactions and tumor heterogeneity [25]. | Captulates emergent behavior from discrete cell-level actions. |

| Multiscale Models | Integrate phenomena across molecular, cellular, and tissue levels [25]. | Combining molecular mechanisms with tissue-level tumour evolution [25]. | Provides a comprehensive, systems-level perspective. |

| Hybrid Models | Combine discrete (e.g., agent-based) and continuous (e.g., continuum) approaches [25]. | Accurately capturing mechanical and biological interactions in a tumor [25]. | Leverages strengths of multiple modeling paradigms for increased accuracy. |

| AI-Driven Systems | Use deep learning to uncover hidden patterns in complex datasets [26]. | Predicting cancer drug sensitivity or detecting tumors in medical images [26]. | Excels at pattern recognition in high-dimensional data (e.g., genomics, radiology). |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols: A Case Study in Clot Contraction

The following section details a specific example of an integrated computational-experimental analysis, providing a reproducible protocol for studying platelet-driven blood clot contraction—a process with significant implications in cancer-associated thrombosis [27].

Integrated Protocol: Computational Modeling of Platelet-Driven Clot Contraction

1. Objective: To quantify the biomechanical kinetics of blood clot contraction driven by platelet-fibrin interactions using a 3D multiscale computational model, and to validate model predictions with experimental observations [27].

2. Background: Blood clot contraction (retraction) is a volumetric shrinkage process driven by activated platelets exerting traction forces on the fibrin network. Impaired contraction is linked to thrombotic risks, including in cancer patients such as those with COVID-19. The role of platelet filopodia (thin membrane protrusions) as the primary mechanical actuators in this process was not well-understood until recently and is a key focus of this integrated analysis [27].

3. Experimental and Computational Workflow:

4. Detailed Experimental Methodology:

- Step 1: Clot Formation and Platelet Activation.

- Procedure: Prepare a 3D in vitro blood clot using human-derived platelets, fibrinogen, and red blood cells suspended in plasma or a physiological buffer. Initiate clotting by adding a physiological agonist such as thrombin (e.g., 0.5-1.0 U/mL) and calcium chloride. Allow the clot to polymerize for 60-90 minutes at 37°C. Activate platelets within the clot using standard agonists like ADP (e.g., 10-20 µM) to stimulate the formation of filopodia [27].

- Step 2: Real-Time Imaging and Data Collection.

- Procedure: Use high-resolution, time-lapse confocal or phase-contrast microscopy to capture the clot contraction process over several hours. Fluorescently label key components—for instance, platelets (e.g., with CD41 antibody) and fibrin (e.g., with a fibrinogen derivative)—to enable visualization of their spatial reorganization. Track key metrics including clot volume over time, platelet cluster formation, and individual platelet-fibrin interactions [27].

- Step 3: Model Calibration and Validation.

- Procedure: Use the quantitative data from Step 2 (e.g., rates of volume shrinkage, final clot density) to calibrate the parameters of the 3D multiscale computational model. Design a new, separate set of experiments under different conditions (e.g., varying platelet count or fibrinogen concentration) to test and validate the predictive accuracy of the calibrated model [27].

5. Computational Model Specifications:

- Model Architecture: The core model is a 3D multiscale representation. It integrates a sub-model for the "hand-over-hand" pulling mechanism of individual platelet filopodia on fibrin fibers, a sub-model capturing the non-linear, strain-stiffening mechanical properties of individual fibrin fibers, and a sub-model of the 3D fibrin network architecture [27].

- Key Parameters:

- Platelet Activation: Represented by the number of filopodia per platelet and the maximum contractile force exerted by each filopod (average maximum measured force is ~29 nN per platelet) [27].

- Biomechanical Feedback: The traction force generated by a filopod is dynamically modulated by the stiffness of the fibrin fiber it is pulling, which increases as the fiber is stretched [27].

- Simulation Execution: The model is run to simulate the temporal evolution of the clot, outputting metrics like overall contraction kinetics, local fibrin density maps, and the formation of platelet-fibrin clusters.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Clot Contraction Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Protocol | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Human Platelets | The primary mechanically active cellular component driving contraction. | Can be isolated from fresh blood samples; concentration should be standardized (e.g., 200,000/µL). |

| Fibrinogen | The structural precursor protein that forms the 3D fibrous scaffold of the clot. | Human plasma-derived; purity >90%. Concentration determines initial network density. |

| Thrombin | A serine protease that converts fibrinogen to fibrin, initiating clot formation. | Used at concentrations from 0.1 to 1.0 U/mL to control the rate of polymerization. |

| Fluorescent Antibodies (e.g., anti-CD41) | Enable high-resolution visualization and tracking of platelets within the 3D clot via microscopy. | Conjugated to fluorophores such as FITC or Alexa Fluor dyes. |

| Activating Agonists (e.g., ADP) | Stimulate platelets to change shape, extend filopodia, and generate contractile forces. | Used at micromolar (µM) concentrations to ensure robust, reproducible activation. |

Validation and Translation: From Models to Clinical Impact

The ultimate value of a computational model lies in its ability to make accurate, testable predictions that provide novel biological insights or improve clinical outcomes. The integrated framework described above successfully demonstrated that the extension and retraction of platelet filopodia are the principal drivers of fibrin network compaction, a finding that was not previously established [27]. Furthermore, the model quantified how the stiffness of the fibrin fiber itself provides biomechanical feedback that modulates the force exerted by the platelet, a key insight into the bidirectional mechanotransduction in this process [27].

This paradigm is being extended to oncology applications. For instance, tools like DeepTarget use AI to integrate large-scale drug and genetic data to predict the primary and secondary targets of small-molecule cancer drugs, outperforming existing methods and offering new avenues for drug repurposing [28]. In clinical imaging, AI models are now being prospectively validated in trials, such as the MASAI trial for mammography, which showed that an AI-assisted workflow could reduce radiologist workload by 44% while maintaining cancer detection performance [26]. The emerging concept of "digital twins"—virtual, patient-specific replicas—aims to use such integrative models to simulate individual disease courses and treatment responses, guiding personalized therapeutic strategies [25].

The Computational Toolkit: Model Frameworks and Their Therapeutic Applications

Computational oncology relies on distinct mathematical paradigms to simulate the complex, multi-scale nature of tumor development and treatment response. Agent-based models (ABM) simulate individual cells, capturing population heterogeneity and emergent behaviors from the bottom up. Continuous models, described by ordinary or partial differential equations (ODEs/PDEs), represent bulk tumor properties and microenvironmental factors as continuous fields. Hybrid modeling frameworks integrate these approaches, coupling two or more mathematical theories to address the inherent limitations of any single method when confronting the vast complexity of cancer biology [29]. These paradigms are foundational to a new, quantitative approach in oncology, enabling in silico experimentation to inform biological discovery and clinical translation.

Foundational Modeling Paradigms

Agent-Based Models (ABM): A Bottom-Up Approach

Agent-based modeling adopts a bottom-up strategy, representing individual cells or entities as discrete "agents" that follow programmed rules for behavior and interaction.

Core Principle and Components: In ABM, each cell is an independent agent with specific properties (e.g., cell type, mutation status, gene expression profile) and behavioral rules (e.g., proliferation, migration, death, interaction). These models excel at simulating the emergence of macroscopic tumor properties from stochastic, microscopic, cell-level events [30] [31]. This makes them particularly suited for studying tumor heterogeneity, clonal evolution, and the spatial dynamics of immune-tumor interactions [30].

Key Application – Adoptive Cell Therapy: The ABMACT framework exemplifies a sophisticated ABM application. It creates "virtual cells" based on immunological knowledge and single-cell RNA-seq data, modeling heterogeneous populations of tumor cells, cytotoxic NK cells (

Nc), exhausted NK cells (NE), and vigilant NK cells (NV). The model incorporates rules for NK cell exhaustion, killing capacity, and serial killing, allowing in silico trials to identify that optimal efficacy requires enhancing immune cell "proliferation, cytotoxicity, and serial killing capacity" [30].Key Application – Precision Prognosis: ABMs are also used for personalized prediction. One study integrated gene expression profiling (GEP) with ABM to improve breast cancer survival forecasts. Genes linked to poor prognosis were identified statistically and their functional effects translated into the rules governing the virtual tumor cells within the ABM. This combined GEP-ABM approach provides a platform to "virtually test different treatments and see how they might affect patient survival" [32].

Continuous Models: Capturing Bulk Dynamics

Continuous models represent tumor cells and microenvironmental factors as continuous densities, using differential equations to describe their temporal and spatial evolution.

Core Principle and Components: These models describe the average behavior of a system, tracking changes in concentrations or volumes over time and space. They are often more computationally efficient for simulating large-scale tumor growth and the diffusion of nutrients, growth factors, or drugs [29]. Common formulations include exponential, logistic, and Gompertz growth models to describe tumor volume dynamics, often coupled with terms for treatment-induced cell kill [33].

Key Application – Predicting Therapy Response in Pancreatic Cancer: A study on murine pancreatic cancer employed a set of ODEs to model tumor volume dynamics under combination therapy (NGC chemotherapy, stromal-targeting drugs, and anti-PD-L1). The model used a treatment-agnostic formulation:

dN/dt = rN(1 - N/K) - N * Σ [α_i * e^(-β(t-τ_i)) * H(t-τ_i)]where

N(t)is tumor volume,ris the proliferation rate,Kis the carrying capacity,α_iis the death rate from treatment, andβis the decay rate of the treatment effect [24]. This model demonstrated high accuracy in fitting and predicting tumor response across different treatment protocols.Key Application – Optimizing Radionuclide Therapy: For [177Lu]Lu-PSMA therapy in prostate cancer, a mathematical model combining the Gompertz tumor growth law with the Linear Quadratic model for radiation-induced cell kill was used. Pharmacokinetic data were integrated to calculate time-dependent dose rates. Simulations revealed that the standard 6-week injection schedule allowed significant tumor regrowth between cycles. The model predicted that a 1-2 cycle schedule with a 2-week interval would maximize tumor reduction and improve outcomes [34].

Hybrid Modeling Frameworks: Integrating Multiple Approaches

Hybrid models combine different mathematical frameworks to overcome the limitations of individual approaches, providing a more comprehensive view of tumor complexity.

Core Principle and Components: The classical definition involves coupling discrete cell-based models with continuous descriptions of diffusible factors [29]. The definition has expanded to include the coupling of any distinct mathematical frameworks, such as:

- Physics-based models (discrete/continuous, fluid dynamics, game theory)

- Data-driven models (machine learning, computer vision)

- Optimization models (optimal control, multi-objective optimization) [29] This integration allows researchers to leverage the strengths of each method, such as using a physics-based model to generate data for training a machine learning algorithm, or using optimal control theory to determine the best treatment schedule simulated by an agent-based model.

Key Application – Simulating Antiangiogenic Therapy: A 3D hybrid model was developed to study the interplay between solid tumor growth, tumor-induced angiogenesis, and the immune response under anti-VEGF treatment. This framework combined a continuous tumor growth model, a discrete model of angiogenesis, and a physiological-based kinetics model for immune cell transport. It was the first to integrate a dynamic, non-regular vascular network, vascular flow, interstitial flow, and the immune system. The model provided mechanistic insights, showing that anti-VEGF therapy works by temporally delaying angiogenesis and normalizing blood vessel structure, which improves perfusion and immune cell infiltration. It also highlighted the critical importance of the "normalization window" for timing treatment [35].

Key Application – A Generalized Hybrid Framework: Another review proposed a holistic hybrid framework that integrates three core classes of models to form a "quantitative decision-making system for personalized medicine." This framework loops together data-driven models (for pattern recognition from clinical/omics data), physics-based models (for simulating biophysical processes), and optimization models (for systematically identifying optimal treatment protocols) [29].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Computational Modeling Paradigms in Oncology

| Feature | Agent-Based Models (ABM) | Continuous Models | Hybrid Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Bottom-up; individual discrete agents (cells) | Top-down; continuous densities or volumes | Integrated; combines two or more mathematical frameworks |

| Core Strengths | Captures heterogeneity, emergent behavior, spatial interactions | Computational efficiency for large-scale dynamics, well-suited for diffusible factors | Mitigates limitations of individual methods; enables comprehensive multi-scale simulation |

| Typical Formulations | Rule-based algorithms; state transitions | ODEs, PDEs (e.g., Logistic, Gompertz) | Discrete cells + continuous fields; ABM + machine learning; ODEs + optimal control |

| Example Applications | ABMACT for NK cell therapy [30]; GEP-ABM for breast cancer prognosis [32] | Pancreatic cancer chemotherapy response [24]; Optimizing [177Lu]Lu-PSMA therapy schedules [34] | Simulating antiangiogenic therapy & immune response [35]; Unified physics-data-optimization frameworks [29] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Developing an ODE Model for Treatment Response

This protocol outlines the steps for creating and calibrating an ODE model to predict solid tumor response to combination therapy, based on a study of murine pancreatic cancer [24].

Model Formulation:

- Select a foundational growth model. The logistic growth model,

dN/dt = rN(1 - N/K), is often used for its ability to represent bounded growth. - Extend the model to incorporate treatment effects. A flexible, treatment-agnostic formulation is:

dN/dt = rN(1 - N/K) - N * Σ [α_i * e^(-β(t-τ_i)) * H(t-τ_i)]where the summation is over each treatment doseiadministered at timeτ_i.

- Select a foundational growth model. The logistic growth model,

Parameter Estimation from Control Data:

- Use tumor volume measurements from an untreated (control) cohort.

- Employ Bayesian parameter estimation or similar fitting procedures to determine the posterior distributions for the population carrying capacity (

K) and mouse-specific proliferation rates (r) and initial volumes (N0). - Validate the fit by calculating metrics like the Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) between simulated and experimental control data.

Parameter Estimation for Treatment Groups:

- Using data from treated cohorts, estimate the treatment parameters (

α,β). - To reduce identifiability issues, fix the carrying capacity

Kto the median value estimated from the control group. - Define the prior distribution for the proliferation rate

rin treatment groups based on the posterior bounds from the control group.

- Using data from treated cohorts, estimate the treatment parameters (

Model Prediction and Validation:

- Perform leave-one-out or mouse-specific predictions using the fitted model.

- Quantify predictive performance using metrics like CCC and Mean Absolute Percent Error (MAPE) to compare simulated tumor volumes with experimental data that was not used for fitting.

Diagram 1: ODE model development and validation workflow.

Protocol: Building an Agent-Based Model for Immunotherapy

This protocol details the process for constructing an ABM to simulate the tumor-immune ecosystem and its response to adoptive cell therapies like CAR-NK cells [30].

Agent Definition and Rule Specification:

- Define Cell Agents: Identify key interacting cell populations (e.g., tumor cells, cytotoxic NK cells

Nc, exhausted NK cellsNE, vigilant NK cellsNV). - Encode Behavioral Rules: Mathematically define rules for agent actions: proliferation, exhaustion, cytotoxic killing, migration, and death. Base these rules on domain knowledge and data from in vitro assays (e.g., autonomous growth and rechallenge assays).

- Define Cell Agents: Identify key interacting cell populations (e.g., tumor cells, cytotoxic NK cells

Integrating Molecular Heterogeneity:

- Utilize paired single-cell RNA-seq and phenotypic data from relevant models (e.g., xenograft mouse models).

- Perform feature selection (e.g., using linear mixed-effect regression) to identify genes and pathways that significantly modulate key cellular functions like cytotoxicity.

- Randomly assign the resulting gene expression profiles to cell agents. Translate these profiles into functional properties (e.g., varying killing rates) using the estimated effects from the regression model.

Model Calibration and Evaluation:

- Calibrate the model by adjusting parameters to match dynamic data from in vivo studies, such as tumor growth curves and immune cell kinetics from mouse models.

- Evaluate the model's ability to recapitulate differential tumor control observed experimentally across different conditions or cancer types.

In Silico Perturbation and Prediction:

- Use the calibrated model as a "digital twin" to run systematic in silico trials.

- Perturb the model to test hypothetical conditions, such as the impact of enhancing specific immune cell functions (proliferation, cytotoxicity) or altering treatment schedules, to predict optimal therapeutic strategies.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools, data types, and theoretical methods that form the essential "research reagents" for developing and applying computational models in oncology.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents in Computational Oncology

| Category | Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools & Platforms | CompuCell3D [25] | A multi-scale modeling environment for simulating cellular behaviors and tissue-level dynamics. |

| SimBiology/MATLAB [34] | A modeling software used for simulating biological systems, such as tumor growth and drug pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics. | |

| IBCell Model [29] | An agent-based model that combines discrete, deformable cells with fluid dynamics equations for cytoplasm. | |

| Data Types | Single-cell RNA-seq Data [30] [32] | Provides high-resolution molecular profiles to parameterize functional heterogeneity and define agent properties in ABMs. |

| Longitudinal Tumor Volume Measurements [24] | Essential experimental data for calibrating and validating model parameters, particularly in ODE/PDE models. | |

| Clinical Histopathology & Imaging Data [29] | Used for model calibration to patient-specific conditions and for generating virtual patient cohorts. | |

| Theoretical & Mathematical Methods | Bayesian Parameter Estimation [24] | A statistical method for inferring model parameters from data, providing estimates of uncertainty. |

| Optimal Control Theory [29] | A mathematical framework used to identify time-dependent treatment protocols that optimize a desired outcome (e.g., tumor shrinkage). | |

| Linear Mixed-Effect Regression [30] | A statistical technique used to identify gene signatures and molecular features that correlate with and modulate cellular functions from omics data. | |

| Model Validation Metrics | Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) [24] | A metric for evaluating the agreement between model predictions and experimental data, assessing both precision and accuracy. |

| Mean Absolute Percent Error (MAPE) [24] | A metric for quantifying the average magnitude of error in model predictions relative to experimental observations. |

Diagram 2: Interaction between core modeling classes in a hybrid framework.

Simulating Angiogenesis and Drug Transport in 3D

Within the field of cancer research, computational tumor models have become indispensable for simulating growth and predicting treatment response. A critical component of these models is the dynamic process of angiogenesis—the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing vasculature. This process is orchestrated by complex biochemical and biophysical cues within the tumor microenvironment (TME), particularly gradients of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) [36] [37]. For tumors to progress beyond a microscopic size, they must co-opt this angiogenic switch to establish a dedicated blood supply for nutrient and oxygen delivery [38]. However, the resulting vasculature is often aberrant, characterized by leakiness and inefficient blood flow, which in turn creates a physical barrier that hampers the delivery of chemotherapeutic agents [39].

The integration of angiogenesis models with drug transport simulation is therefore paramount for enhancing the predictive power of in silico oncology and developing more effective therapeutic strategies. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for building and validating such integrated models, framed within a broader thesis on computational tumor models.

Computational Modeling Approaches

Computational models offer a multifaceted toolkit to dissect the angiogenesis and drug delivery process across different scales, from intracellular signaling to tissue-level vascular network formation.

Signaling Pathway Models

At the molecular scale, mechanistic models simulate intracellular signaling to predict phenotypic outputs like endothelial cell permeability and proliferation.

Key Model Formulation:

A deterministic ordinary differential equation (ODE) model can be constructed to capture the core interactions between VEGF and Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF), which have contrasting effects on vascular permeability [40]. The system dynamics for each species can be represented as:

d[Species]/dt = Production - Decay - Complex_Formation + Activation

This model incorporates key receptors (VEGFR2, c-MET), ligands (VEGF, HGF), and downstream effectors like RAC1 and PAK1. A critical model feature is the tracking of site-specific phosphorylation on PAK1 (e.g., T423, S144), which is hypothesized to drive differential cellular responses to VEGF and HGF stimulation [40].

Table 1: Key Parameters for a VEGF-HGF Signaling Model

| Parameter | Description | Estimated Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|