Conquering Cancer Complexity: Advanced Strategies to Overcome Tumor Heterogeneity in Therapeutic Development

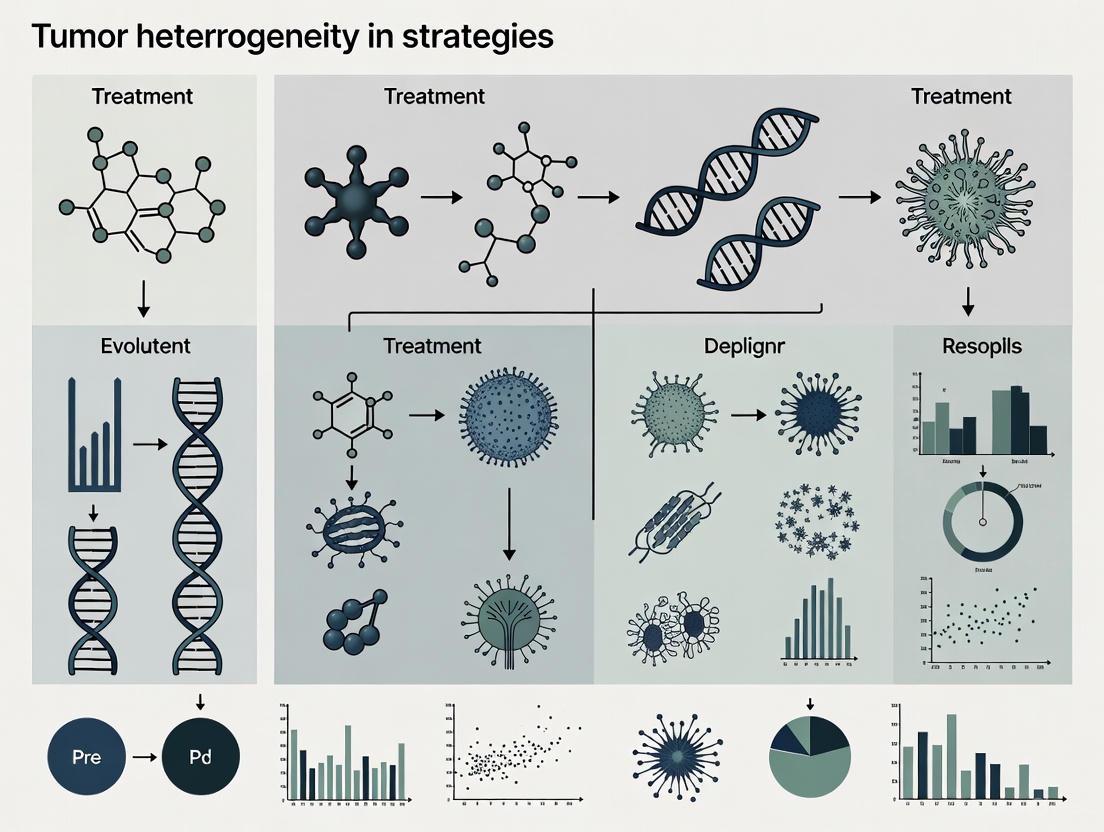

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical challenge of tumor heterogeneity in oncology.

Conquering Cancer Complexity: Advanced Strategies to Overcome Tumor Heterogeneity in Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical challenge of tumor heterogeneity in oncology. It explores the fundamental biological mechanisms driving intra- and inter-tumoral diversity, examines cutting-edge methodological approaches for characterization and targeting, addresses key hurdles in treatment resistance and biomarker development, and evaluates validation frameworks for novel strategies. By synthesizing foundational concepts with emerging clinical applications, this review aims to bridge the gap between mechanistic understanding and therapeutic innovation, offering a roadmap for developing more effective, heterogeneity-informed cancer treatments.

Decoding the Complex Landscape: Understanding the Biological Basis of Tumor Heterogeneity

Defining Spatial and Temporal Heterogeneity in Solid Tumors

Tumor heterogeneity, the presence of distinct cell subpopulations with different genetic, phenotypic, and behavioral characteristics within a single tumor or between tumors, represents a fundamental challenge in oncology research and therapeutic development [1] [2]. This variability exists across two critical dimensions: spatial heterogeneity (differences across different geographical regions of a single tumor or between primary and metastatic sites) and temporal heterogeneity (changes that occur over time through tumor evolution and in response to therapies) [1] [3]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and accounting for this heterogeneity is crucial for designing effective treatment strategies and avoiding therapeutic resistance.

Spatial heterogeneity manifests as an uneven distribution of tumor cell subpopulations with different molecular characteristics between and within disease sites [1] [3]. Temporal heterogeneity refers to the dynamic changes in cancer cell molecular composition that occur over time, either through natural evolution or in response to selective pressures like drug treatment [1] [3]. These two dimensions of heterogeneity create complex, evolving ecosystems that can confound traditional single-biopsy diagnostic approaches and lead to treatment failure through the selection of resistant subclones.

FAQs: Core Concepts for Researchers

Q1: What are the fundamental mechanisms driving spatial and temporal heterogeneity in solid tumors?

Several interconnected biological mechanisms drive heterogeneity in solid tumors:

- Genomic Instability: Cancer cells exhibit higher mutation rates than normal cells due to defects in DNA repair, telomere maintenance, DNA replication, and chromosome segregation. This creates extensive genetic diversity that serves as the substrate for heterogeneity [1] [4]. The mutation rate per trillion bases across 12 major cancer types ranges from 0.28 to 8.15 [1].

- Clonal Evolution: This Darwinian model proposes that genetically unstable cells accumulate alterations over time, and selective pressures favor the growth and survival of variant subpopulations with a fitness advantage [5] [2]. This can follow linear patterns (successive acquisition of mutations) or, more commonly in solid tumors, branching evolution where multiple genetically distinct populations form from a common ancestor [4].

- Epigenetic Modifications: Changes in DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling can create stable, heritable phenotypic diversity without altering the DNA sequence itself. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) may generate cellular heterogeneity through epigenetic mechanisms, establishing a differentiation hierarchy within tumors [1] [6].

- Microenvironmental Influences: The tumor microenvironment (TME), including gradients of oxygen, nutrients, and stromal cell interactions (e.g., fibroblasts, immune cells), exerts selective pressures that shape heterogeneity. Variations in blood supply can create distinct niches that favor different subclones [1] [7].

Q2: How does tumor heterogeneity confound biomarker discovery and validation?

Heterogeneity introduces significant challenges in biomarker development:

- Sampling Bias: A single core biopsy or fine needle aspirate may not capture the full spectrum of molecular alterations present in different tumor regions or metastatic sites [5]. For example, in renal cell carcinoma, only about 34% of mutations were consistent across all samples from the same primary tumor and its metastases [1]. This can lead to false-negative results for important biomarkers.

- Temporal Dynamics: A biopsy represents a single moment in a tumor's evolution. The genomic landscape can change substantially over time, particularly under therapeutic selective pressure, meaning diagnostic results can quickly become outdated [1] [5]. For instance, in NSCLC patients treated with EGFR-TKIs, the T790M resistance mutation positivity rate in plasma increases with longer treatment duration [1].

- Incomplete Target Representation: Targeted therapies selected based on a single biopsy may only be effective against a subpopulation of tumor cells, leaving resistant clones to eventually cause disease progression [2].

Q3: What experimental strategies can accurately capture spatial heterogeneity?

To overcome spatial sampling limitations, researchers are employing several advanced strategies:

- Multi-Region Sequencing: Sampling multiple geographically distinct regions from a single tumor during surgical resection provides a more comprehensive genetic profile. For clear cell renal carcinoma, some researchers recommend sampling at least three different regions to ensure accuracy of key mutation tests [1].

- Single-Cell Sequencing: This technology enables the characterization of individual cells within a diverse population, defining complex clonal relationships and revealing rare subpopulations that bulk sequencing would miss [4].

- Radiogenomics and Habitat Imaging: Advanced imaging techniques (MRI, CT, PET/CT) can non-invasively map phenotypic heterogeneity across entire tumors. Quantitative imaging features (radiomics) can be correlated with genomic data to identify region-specific biological characteristics [8].

- Computer Vision and Digital Pathology: Machine learning applied to digitized histology slides can automatically identify and map various cell types (tumor, immune, stromal) across tissue sections, providing quantitative spatial context for cellular interactions within the TME [7].

Q4: How can we effectively monitor temporal heterogeneity throughout disease progression and treatment?

Monitoring temporal heterogeneity requires longitudinal assessment strategies:

- Liquid Biopsies and Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA): Serial analysis of ctDNA from blood samples allows for non-invasive, repeated monitoring of clonal dynamics and the emergence of resistance mutations during therapy [9]. This provides a composite snapshot of heterogeneity from multiple tumor sites.

- Serial Biopsies: When feasible and ethically justified, obtaining tumor tissue at key time points (e.g., at progression) can directly reveal evolutionary changes. However, this is invasive and not always possible [5] [2].

- Patient-Derived Model Systems: Establishing patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) or organoids from different time points can preserve and allow functional study of evolving subclones [2].

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent Results from Different Tumor Regions

Problem: Molecular profiling results (e.g., mutation status, gene expression) vary dramatically between samples taken from different regions of the same tumor, leading to conflicting data.

| Potential Cause | Solution | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate sampling | Implement systematic multi-region sampling protocol. For research on surgical specimens, sample from central, peripheral, and intermediate zones, noting spatial coordinates. | Logistically challenging for advanced cancers; sample number must be balanced against tumor size [1]. |

| True extensive spatial heterogeneity | Use imaging-guided biopsy to target regions with distinct radiological features (e.g., hypoxic vs. well-perfused areas). | Requires coordination with radiology department; specialized equipment needed. |

| Analysis of bulk tissue | Employ single-cell sequencing technologies to deconvolute cellular mixtures and identify minority subclones. | Higher cost and computational burden for data analysis [4]. |

Experimental Workflow for Multi-Region Analysis:

- Sample Collection: For resectable tumors, immediately following resection, photograph the specimen and dissect multiple (e.g., 3-5) regions representing different macroscopic appearances (e.g., necrotic core, invasive front, well-defined region).

- Spatial Annotation: Record the precise location of each sample within the tumor. Snap-freeze a portion of each sample in liquid nitrogen and preserve the remainder in formalin for parallel histology.

- Pathological Validation: Perform H&E staining on adjacent sections to confirm tumor content and assess necrosis, immune infiltration, and other histological features for each region.

- DNA/RNA Co-Isolation: Extract nucleic acids from the same tissue piece to enable direct correlation of genomic and transcriptomic data from the same cellular context.

- Parallel Sequencing: Conduct whole-exome or targeted sequencing, and RNA sequencing on all regional samples simultaneously using the same sequencing platform and batch to minimize technical variation.

- Bioinformatic Integration: Use phylogenetic tree analysis to reconstruct evolutionary relationships between regional samples and spatial mapping software to visualize the distribution of clones.

Spatial Heterogeneity Analysis Workflow

Challenge 2: Emergence of Treatment Resistance After Initial Response

Problem: Targeted therapies often produce dramatic initial responses, followed by relapse due to outgrowth of pre-existing or newly acquired resistant subclones.

| Potential Cause | Solution | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-existing resistant minor subclone | Use highly sensitive NGS assays (e.g., with error correction) on pre-treatment samples to detect low-frequency resistant clones. | Requires deep sequencing coverage; clinical significance of very low-frequency variants may be unclear. |

| Acquired resistance evolution | Implement longitudinal liquid biopsy monitoring (ctDNA) during treatment to track clonal dynamics in real-time. | ctDNA levels can be low in some cancer types; may not capture all resistance mechanisms. |

| Adaptive bypass signaling | Design combination therapies upfront that target primary driver and common resistance pathways simultaneously. | Increased risk of toxicity; requires robust preclinical validation of synergy. |

Protocol for Longitudinal ctDNA Monitoring for Temporal Heterogeneity:

- Baseline Sample Collection: Collect plasma (e.g., 2x10mL Streck tubes) and matched germline DNA (saliva or blood) prior to initiation of therapy.

- Plasma Processing: Process within 6 hours of collection. Centrifuge to isolate plasma, then a second high-speed centrifugation to remove residual cells.

- ctDNA Extraction: Use commercially available circulating nucleic acid kits for extraction.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Use NGS panels designed for your cancer type, covering primary driver mutations and known resistance mechanisms. Unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) are critical for error correction and accurate variant calling.

- Schedule for Serial Monitoring: Collect additional plasma samples at defined intervals (e.g., every 4-8 weeks during treatment, and at time of radiographic progression).

- Variant Calling and Clonal Tracking: Bioinformatically identify somatic variants and track their variant allele frequencies (VAFs) over time. Rising VAFs of a specific mutation suggest selective outgrowth of a resistant subclone.

Temporal Heterogeneity Monitoring Approach

Challenge 3: Integrating Complex Heterogeneity Data into Actionable Insights

Problem: Multi-region and single-cell sequencing generate vast, complex datasets that are difficult to interpret and translate into therapeutic strategies.

Solutions and Considerations:

- Computational Clonal Deconvolution: Use bioinformatic tools (e.g., PyClone, SciClone) to estimate the number and prevalence of distinct subclones and their mutational composition from bulk sequencing data of multiple samples [2].

- Phylogenetic Tree Reconstruction: Apply algorithms used in evolutionary biology to infer the ancestral relationships between different tumor subclones, distinguishing early "truncal" events (present in all subclones) from later "branch" events (private to specific subclones) [2].

- Functional Validation of Targets: Prioritize therapeutic targeting of "truncal" mutations present in all subclones. For branch-specific resistance mutations, use in vitro models (e.g., CRISPR-engineered isogenic cell lines) to confirm functional impact and drug sensitivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and technologies for studying tumor heterogeneity.

| Research Tool | Primary Function | Key Application in Heterogeneity Research |

|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) [1] [5] | High-throughput DNA/RNA sequencing. | Comprehensive profiling of genetic alterations across multiple tumor regions or time points. |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) [4] | Transcriptome profiling of individual cells. | Deconvoluting cellular composition, identifying rare cell states, and reconstructing trajectories of cellular differentiation and plasticity within tumors. |

| Liquid Biopsy Kits (ctDNA extraction) | Isolation of cell-free DNA from blood plasma. | Non-invasive longitudinal monitoring of clonal dynamics and emergence of resistance mutations during therapy [9]. |

| Multiplex Immunofluorescence (mIF) | Simultaneous detection of multiple protein markers on a single tissue section. | Spatial profiling of the tumor immune microenvironment, revealing interactions between specific tumor subclones and immune cell populations [7]. |

| Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) | 3D ex vivo cultures derived from patient tumor tissue. | Functional testing of drug sensitivity on a patient-specific basis, potentially capturing some of the original tumor's heterogeneity [2]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences added to each DNA fragment during library prep. | Error correction in NGS data, enabling accurate detection of low-frequency variants critical for identifying minor subclones. |

| Digital Pathology Software [7] | Machine learning-based image analysis of whole slide images. | Quantitative analysis of spatial relationships between different cell types, and identification of histologically distinct regions for targeted sampling. |

The table below consolidates quantitative findings from studies on tumor heterogeneity, providing reference points for researchers designing and interpreting experiments.

| Metric | Value / Range | Context / Implication | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Heterogeneity (Mutation Concordance) | ~34% | Proportion of mutations found consistently across all regions of a primary renal tumor and its metastases. Highlights extensive spatial divergence. | [1] |

| Driver Mutation Heterogeneity in NSCLC | >75% | Proportion of tumor driver mutations that were heterogeneous (not present in all regions) in early-stage NSCLC. | [1] |

| Range of Mutation Rates | 0.28 - 8.15 per megabase | The variation in mutation rates found across 12 major categories of cancer, underlying the variable substrate for heterogeneity. | [1] |

| Oncogenic Driver Detection Rate | 64% | Proportion of 733 lung cancer patients in the LCMC study whose tumors had a detectable oncogenic driver. | [5] |

| Average Genomic Alterations in NSCLC | 10.8 per sample | The average number of genomic alterations found per sample in an NGS study of 364 NSCLC patients, indicating inherent complexity. | [5] |

Addressing spatial and temporal heterogeneity is not merely a technical challenge but a paradigm shift in cancer research. Moving forward, successful therapeutic strategies will need to be inherently dynamic and multi-faceted. This includes the development of rational combination therapies that target both truncal drivers and common resistance pathways, the integration of liquid biopsies into clinical trial designs for real-time adaptive therapy, and a greater focus on targeting the tumor ecosystem itself—including the immune compartment and stromal elements—to reduce the adaptive capacity of heterogeneous tumors. By adopting the sophisticated sampling, analytical, and monitoring tools outlined in this guide, researchers can deconstruct heterogeneity from an obstacle into a roadmap for designing more durable and effective cancer treatments.

Foundational Concepts & Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How do the Clonal Evolution and Cancer Stem Cell (CSC) models explain tumor heterogeneity, and are they mutually exclusive?

A: The Clonal Evolution model posits that tumors are a mosaic of subpopulations of cells that have accumulated diverse mutations over time. Darwinian selection acts on this genetic diversity, favoring the expansion of clones with a fitness advantage (e.g., faster proliferation or resistance to therapy) within a given microenvironment [10]. In contrast, the CSC model proposes a hierarchical organization where only a small subset of cells, the CSCs, possess the ability to self-renew and differentiate into the heterogeneous lineages of cancer cells that constitute the tumor [10].

These models are not mutually exclusive. Evidence suggests that CSCs themselves can be a product of clonal evolution. Somatic evolution can select for cancer cells that acquire "stemness" traits, such as upregulation of drug-efflux proteins and pro-survival signaling pathways, which impart a significant fitness advantage. Therefore, clonal selection for stem cell characteristics may result in the emergence of CSCs within a tumor [10].

Q2: What are the key practical implications of these models for therapy and drug resistance?

A: The two models have distinct but overlapping implications for treatment failure:

- Clonal Evolution: Drug resistance arises from the pre-existence or spontaneous development of genetically resistant subclones. Treatment acts as a selective pressure, eliminating sensitive cells and allowing resistant clones to expand. This resistance is typically irreversible as it is genetically encoded [11].

- Cancer Stem Cell: CSCs are often inherently resistant to conventional therapies due to properties like quiescence, enhanced DNA repair, and expression of drug-efflux pumps (e.g., ABC transporters). Eradicating the CSC population is considered crucial for achieving long-term remission, as they can regenerate the tumor. Resistance can also involve reversible, non-genetic plasticity, where cells change their functional state to adapt to therapeutic pressure [10] [11].

Modern treatment strategies must account for both irreversible genetic resistance and reversible cellular plasticity [11].

Q3: How is intratumoral heterogeneity investigated experimentally?

A: Key methodologies include:

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): This powerful technique allows researchers to profile the transcriptomes of individual cells within a tumor, revealing distinct cell subtypes, states, and lineage relationships. It is instrumental in classifying molecular subtypes and understanding cellular plasticity [12] [13].

- Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDXs): Transplanting patient tumor tissue into immunodeficient mice preserves the original tumor's heterogeneity and architecture. PDX models are used to study tumor growth, metastasis, and therapy response in a context that closely mimics the patient's disease [12].

- Mathematical Modeling: Computational frameworks simulate the population dynamics of tumor subclones and their response to treatments. These models can incorporate both genetic evolutionary dynamics and non-genetic plasticity to predict optimal therapeutic sequences and combat resistance [11].

Key Quantitative Data

Table 1: Frequently Mutated Cancer Gene Categories Across Human Cancers (Analysis of 20,331 tumors, 41 cancer types) [14]

| Gene Category | Example Genes | Percentage of Tumors with Mutations in Category |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor Suppressor Genes | TP53, PTEN, CSMD3 | 94% |

| Oncogenes | KRAS, PIK3CA, MUC16 | 93% |

| Transcription Factors | TP53, KMT2C | 72% |

| Kinases | PIK3CA, BRAF, ATM | 64% |

| Cell Surface Receptors | MUC16, LRP1B | 63% |

| Phosphatases | PTPRT, PTEN | 22% |

Table 2: Molecular Subtypes of Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC) and Their Characteristics [12]

| Subtype | Defining Transcription Factor | Key Characteristics | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCLC-A | ASCL1 | High neuroendocrine (NE) differentiation; classic floating aggregates. | More susceptible to first-line chemotherapy (cisplatin). |

| SCLC-N | NEUROD1 | High neuroendocrine differentiation; more prevalent in lymph node/distant metastases. | More susceptible to first-line chemotherapy (cisplatin). |

| SCLC-P | POU2F3 | Non-neuroendocrine; adherent cell morphology; may undergo EMT. | Potential target for novel therapies. |

| SCLC-I | (Inflammatory) | Low ASCL1/NEUROD1/POU2F3; high inflammatory/immune markers. | More responsive to immunotherapy (PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Investigating Tumor Heterogeneity and Subtype Plasticity Using scRNA-seq

Application: Classifying molecular subtypes of a tumor (e.g., SCLC) and tracking subtype shifts in response to therapy [12] [13].

- Sample Preparation: Obtain fresh tumor tissue from a primary or metastatic site. For therapy response studies, collect paired samples (pre- and post-treatment).

- Single-Cell Suspension: Dissociate the tissue into a single-cell suspension using mechanical and enzymatic (e.g., collagenase) digestion. Filter through a cell strainer to remove clumps.

- scRNA-seq Library Preparation: Use a platform like the 10x Genomics Chromium to capture individual cells, barcode their RNA, and prepare sequencing libraries.

- Sequencing & Data Processing: Perform high-throughput sequencing on an Illumina platform. Align sequences to a reference genome and generate a gene expression matrix (cells x genes).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control: Filter out low-quality cells (high mitochondrial gene percentage, low unique gene counts).

- Clustering & Visualization: Use dimensionality reduction techniques (PCA, UMAP) and graph-based clustering (e.g., Seurat, Scanpy) to identify distinct cell populations.

- Subtype Annotation: Identify clusters based on the expression of known marker genes (e.g., ASCL1 for SCLC-A, POU2F3 for SCLC-P, CD3D for T-cells).

- Trajectory Inference: Apply algorithms (e.g., Monocle, PAGA) to infer potential lineage relationships and plasticity between subtypes.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Treatment Efficacy and Resistance In Vivo Using PDX Models

Application: Testing personalized treatment sequences and monitoring the emergence of resistant subclones [12] [11].

- Model Generation: Implant patient-derived tumor fragments or cells subcutaneously or orthotopically into immunodeficient mice (e.g., NSG mice).

- Treatment Cohorts: Once tumors are established (e.g., ~100-150 mm³), randomize mice into different treatment arms (e.g., Drug A, Drug B, combination, sequential therapy, or vehicle control).

- Treatment and Monitoring: Administer therapies according to the designated schedule. Measure tumor volumes and mouse weights 2-3 times per week.

- Endpoint Analysis:

- Harvest Tumors: At the end of the study, harvest tumors from all cohorts.

- Downstream Applications: Analyze tumors via:

- Genomic DNA sequencing to track the evolution of specific genetic subclones.

- scRNA-seq (as in Protocol 1) to profile cellular heterogeneity and identify shifts in subtype composition post-treatment.

- IHC/Flow Cytometry to validate protein-level markers of resistance or subtype identity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating Genetic Drivers and Heterogeneity

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Collagenase/Hyaluronidase | Enzymatic digestion of solid tumor tissue to create single-cell suspensions for scRNA-seq or flow cytometry [13]. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Essential component of cell culture media for growing and maintaining patient-derived cells or established cancer cell lines. |

| Matrigel | Basement membrane extract used for 3D cell culture (organoids) and to support the engraftment and growth of PDX models. |

| DMSO (Cryopreservation Medium) | Used for the cryopreservation of viable tumor cells, organoids, and tumor fragments for long-term storage and biobanking. |

| Antibodies for Flow Cytometry (e.g., anti-CD44, anti-CD133) | Used to identify and isolate potential Cancer Stem Cell populations via Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS). |

| CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Assay | A homogeneous method used to determine the number of viable cells in culture based on quantitation of ATP, useful for drug screening. |

| TRIzol Reagent | A monophasic solution of phenol and guanidine isothiocyanate for the isolation of high-quality total RNA from cells and tissues for sequencing. |

Signaling Pathways & Experimental Workflows

Treatment Resistance Logic

SCLC Analysis Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Investigating Epigenetic Drug Tolerance in Cell Models

Problem: A subset of cancer cells survives initial drug treatment, showing no genetic mutations, suggesting a non-genetic, reversible resistance.

Investigation Framework:

- Confirm Non-Genetic Basis: Perform whole-exome sequencing on parental and drug-tolerant persister (DTP) cells to rule out acquired genetic mutations [15].

- Profile Epigenetic State: Use chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) for histone marks (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27me3) and whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) for DNA methylation in both cell populations [16] [17].

- Test for Phenotypic Plasticity:

- Conduct a drug withdrawal assay; non-genetic resistance often leads to re-sensitization after several cell divisions in a drug-free medium [15].

- Use single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to identify distinct cellular states (e.g., stem-like, mesenchymal) and their transitions upon drug pressure [18].

- Identify Key Epigenetic Regulators: Perform a functional CRISPR screen targeting epigenetic "writers," "readers," and "erasers" in DTP cells to identify enzymes essential for survival [16] [17].

Solution: The acquired resistance is likely stable non-genetic resistance mediated by heritable epigenetic reprogramming. Combination therapy with an epigenetic drug (e.g., DNMT or EZH2 inhibitor) and the original anticancer agent may prevent or reverse this resistance [16] [15].

Guide 2: Overcoming Resistance to KRAS G12C Inhibitors

Problem: Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients develop resistance to KRAS G12C inhibitors (e.g., sotorasib, adagrasib) without secondary genetic mutations in ~50% of cases [19].

Investigation Framework:

- Analyse Protein Interaction Networks: Use co-immunoprecipitation followed by mass spectrometry to investigate if drug binding alters KRAS conformational dynamics and rewires its interactions with partner proteins [19].

- Assess Transcriptional Reprogramming: Perform RNA-seq on resistant cells to identify upregulated bypass signaling pathways (e.g., RTK, MAPK) [19].

- Evaluate Phenotypic Plasticity: Use flow cytometry to track markers of cellular differentiation states; resistance is frequently associated with a shift towards a stem-like or de-differentiated phenotype [15].

Solution: Resistance emerges from a nexus of non-genetic and genetic mechanisms. A combination of KRAS G12C inhibitors with other agents is a primary strategy. Preclinical data suggests that combining sotorasib with the proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib can alleviate this resistance [19].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the difference between genetic and non-genetic drug resistance in cancer?

Answer: Genetic resistance is caused by permanent mutations in the DNA sequence that are selectively amplified under treatment pressure. In contrast, non-genetic resistance involves reversible changes in gene expression that do not alter the underlying DNA sequence. This is often driven by epigenetic modifications (e.g., DNA methylation, histone modifications) and phenotypic plasticity, allowing cancer cells to dynamically switch between drug-sensitive and drug-tolerant states [15].

FAQ 2: How does phenotypic plasticity contribute to therapy failure?

Answer: Phenotypic plasticity is the ability of a cancer cell to change its identity and functional state in response to environmental cues, such as drug treatment. For example, in Glioblastoma (GBM), standard chemo-radiation therapy can reprogram non-stem tumor cells to acquire stem-like characteristics (de-differentiation) or transdifferentiate into vascular-like cells. This plasticity generates cellular heterogeneity and fosters the outgrowth of therapy-resistant cell populations that drive tumor recurrence [18].

FAQ 3: What are the main epigenetic mechanisms driving this plasticity and resistance?

Answer: The core mechanisms, which are frequently dysregulated in cancer, are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Epigenetic Mechanisms in Cancer Therapy Resistance

| Mechanism | Description | Role in Resistance |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation | Addition of methyl groups to cytosine bases in DNA, typically leading to gene silencing. | Hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters (e.g., P16, RASSF1A) silences them, aiding cell survival. Global hypomethylation can cause genomic instability and oncogene activation [16] [20] [21]. |

| Histone Modifications | Post-translational changes (e.g., acetylation, methylation) to histone proteins that alter chromatin structure. | Alterations in marks like H3K27ac (activation) and H3K27me3 (repression) reprogram the transcriptome, promoting survival and stemness. For instance, radiation can induce histone modifications that drive a proneural-to-mesenchymal transition in GBM, increasing invasiveness and resistance [16] [18]. |

| RNA Modifications (Epitranscriptomics) | Chemical modifications to RNA molecules, such as N6-methyladenosine (m6A), that regulate their fate. | m6A modifications impact RNA stability and translation of key transcripts involved in drug metabolism, DNA repair, and cellular survival pathways [16] [20]. |

| Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) | RNA molecules that do not code for proteins but regulate gene expression (e.g., miRNAs, lncRNAs). | ncRNAs can function as master regulators, fine-tuning the expression of entire networks of genes involved in cell death, proliferation, and stemness, thereby modulating the tumor's response to therapy [16] [21]. |

FAQ 4: Can non-genetic resistance become stable and heritable?

Answer: Yes. While some forms like drug-tolerant persisters (DTPs) are transient, non-genetic changes can lead to stable, mitotically active resistance. This occurs through epigenetic heterogeneity and selection, where pre-existing or induced cell subpopulations with stable, heritable epigenetic states that confer resistance are expanded under therapeutic pressure [15].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Generating and Characterizing Drug-Tolerant Persister (DTP) Cells

Purpose: To establish a model of reversible, non-genetic drug resistance in vitro [15].

Materials:

- Cancer cell line of interest

- Cytotoxic or targeted anticancer drug

- Cell culture reagents and equipment

Method:

- DTP Induction: Treat a confluent monolayer of cancer cells with a high concentration of the drug (e.g., 10x IC50) for an extended period (e.g., 5-9 days). Include a DMSO vehicle control.

- DTP Isolation: After treatment, a small fraction of surviving, non-proliferating cells will remain adherent. Wash and maintain these cells in fresh drug-containing media; these are the DTPs.

- Characterization:

- Reversibility Assay: Wash DTPs and culture them in drug-free media. Monitor for regrowth and re-test drug sensitivity after 2-3 weeks to confirm re-sensitization.

- Molecular Profiling: Extract RNA and protein from DTPs and parental cells for transcriptomic (RNA-seq) and proteomic analysis to identify upregulated resistance pathways.

Protocol 2: Assessing DNA Methylation Status via Bisulfite Sequencing

Purpose: To map genome-wide DNA methylation patterns and identify hyper/hypomethylated regions associated with resistance [20] [17].

Materials:

- Genomic DNA from sensitive and resistant cells

- Bisulfite conversion kit (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation Kit)

- Next-generation sequencing platform and bioinformatics tools

Method:

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat 500 ng - 1 µg of genomic DNA with sodium bisulfite. This converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils (which are read as thymines in sequencing), while methylated cytosines remain unchanged.

- Library Prep & Sequencing: Prepare a sequencing library from the converted DNA and run on an NGS platform.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Align sequences to a bisulfite-converted reference genome.

- Calculate methylation percentage per cytosine as

# reads with 'C' / (# reads with 'C' + # reads with 'T'). - Identify Differentially Methylated Regions (DMRs) between sensitive and resistant cells, focusing on promoter CpG islands.

Table 2: Quantitative Data on KRAS G12C Inhibitor Combination Trials

| Combination Therapy | Clinical Trial | Response Rate | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adagrasib + Pembrolizumab (anti-PD1) | KRYSTAL-1 / KRYSTAL-7 | 49% - 57% | Combination was well-tolerated, but response rates were not significantly improved over monotherapy in some contexts [19]. |

| Sotorasib + Trametinib (MEK inhibitor) | CodeBreak 101 | 20% (sotorasib-naïve); 0% (sotorasib-resistant) | The combination showed limited efficacy, particularly in patients with prior resistance to KRAS inhibition [19]. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Therapy-Induced Plasticity

DTP Investigation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Epigenetic Plasticity Studies

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNMT Inhibitors (e.g., 5-Azacytidine, Decitabine) | Inhibit DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), causing passive DNA demethylation and reactivation of silenced genes. | Test if reversing promoter hypermethylation re-sensitizes resistant cells to therapy [16] [21]. |

| HDAC Inhibitors (e.g., Vorinostat, Panobinostat) | Inhibit histone deacetylases (HDACs), leading to increased histone acetylation and a more open, transcriptionally permissive chromatin state. | Use in combination with other agents to disrupt the epigenetic state that maintains resistance [16]. |

| EZH2 Inhibitors (e.g., Tazemetostat) | Inhibit EZH2, the catalytic subunit of PRC2, which is responsible for depositing the repressive H3K27me3 mark. | Target the epigenetic maintenance of a stem-like or de-differentiated state in resistant cells [16] [18]. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Chemically modify DNA for downstream analysis, distinguishing methylated from unmethylated cytosines. | Prepare samples for whole-genome bisulfite sequencing to map DNA methylation patterns [20] [17]. |

| ChIP-Grade Antibodies | Highly specific antibodies for immunoprecipitating DNA-protein complexes. Essential for ChIP-seq. | Perform ChIP-seq for histone marks (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K27me3) to map the chromatin landscape [16] [17]. |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq Kits | Enable transcriptome profiling at the single-cell level to resolve cellular heterogeneity and state transitions. | Identify rare subpopulations (e.g., DTPs) and trace lineage trajectories during acquired resistance [18]. |

The Tumor Microenvironment's Role in Shaping Heterogeneity

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Why does my preclinical drug candidate show efficacy in vitro but fail in animal models, and how can TME heterogeneity explain this?

A: This common failure often stems from the inability of simple in vitro models to capture the complex cellular interactions and physical barriers present in actual tumor microenvironments. 2D cell lines lack the three-dimensional architecture and cellular diversity of real tumors [22].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Implement advanced models: Transition to more physiologically relevant models such as Patient-Derived Organoids and Patient-Derived Xenografts that better preserve original tumor characteristics and some TME components [22].

- Analyze spatial relationships: Use multiplex immunohistochemistry to determine if your drug target is located in inaccessible tumor regions (e.g., surrounded by dense fibrosis) [23].

- Profile TME composition: Characterize the model's CAF subpopulations, immune cell infiltration, and extracellular matrix composition using single-cell RNA sequencing to identify potential resistance mechanisms [24] [25].

Q2: How can I determine if observed drug resistance is due to pre-existing tumor cell heterogeneity or TME-mediated adaptation?

A: Distinguishing between these resistance mechanisms requires integrated analysis of both cancer cell-intrinsic factors and microenvironmental influences over time.

Experimental Approach:

- Establish baseline heterogeneity: Perform single-cell RNA sequencing on untreated control samples to identify pre-existing subpopulations with different transcriptional profiles (e.g., mesenchymal-like, luminal-like, basal-like cells) [26].

- Track clonal dynamics: Use barcoding technologies or CNV analysis to monitor how different subclones expand or contract during treatment [26] [27].

- Correlate with TME changes: Analyze parallel changes in stromal and immune cell composition using the same single-cell data to identify TME factors associated with resistant subclones [26] [25].

Table 1: Key Analytical Methods for Investigating Resistance Mechanisms

| Method | Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Single-cell RNA sequencing | Simultaneous profiling of malignant and stromal cell populations; identification of pre-existing and emergent subpopulations | Requires fresh or properly preserved tissue; computational expertise needed for data analysis [26] [25] |

| Multiplex immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Spatial analysis of protein expression in intact tissue architecture; cell-cell interaction studies | Panel design crucial; antibody validation required; tissue morphology preservation [23] [27] |

| Spatial transcriptomics | Mapping gene expression to tissue locations; correlation of heterogeneity with histological features | Lower resolution than single-cell; integration with H&E staining recommended [25] |

| Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDX) | Study of human tumors in in vivo context while preserving some TME components; drug response studies | Immune-deficient hosts limit immune interactions; stromal cells eventually replaced by mouse cells [22] |

Q3: What biomarkers can I use to enrich patient populations for early-phase immunotherapy trials to avoid false negative results?

A: The Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer recommends biomarker-based enrichment strategies to increase the likelihood of detecting clinical signals in early-phase trials [28].

Enrichment Framework:

- For T-cell-targeting agents: Start with CD8+ IHC to identify tumors with T-cell infiltration, then retrospectively develop more precise biomarkers using multiomics [28].

- For non-T-cell targeting agents: Select enrichment biomarkers based on preclinical data showing pathway modulation, such as:

- Tertiary lymphoid structures (CD20+ B cells)

- Myeloid cells (CD68+, CD163+)

- Fibroblast subsets

- Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio [28]

Table 2: TME-Based Biomarkers for Patient Enrichment in Clinical Trials

| Biomarker Category | Specific Markers | Detection Method | Enrichment Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-cell Inflammation | CD8+, CD3+, PD-L1 | IHC, multiplex IHC | ICIs, T-cell engagers [28] [27] |

| Myeloid Cells | CD68 (macrophages), CD163 (M2-like TAMs) | IHC, flow cytometry | Myeloid-targeting agents [28] |

| Tertiary Lymphoid Structures | CD20+ B cells, DC-LAMP+ dendritic cells | Multiplex IHC, H&E | Prognostic assessment, response prediction [28] |

| Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts | α-SMA, FAP, PDGFRβ | IHC, single-cell RNA-seq | Stroma-modifying therapies [24] [25] |

| Tumor Mutational Burden | Whole exome sequencing | NGS | ICIs in certain cancer types [28] |

Q4: How can I account for spatial heterogeneity when analyzing biopsy samples for clinical trial stratification?

A: Spatial heterogeneity presents significant challenges for accurate biomarker assessment, as single biopsies may not represent the entire tumor's biology [27].

Best Practices:

- Multi-region sampling: Obtain 3-5 core biopsies from different tumor regions when possible, avoiding fine needle aspirations which disrupt architecture [28].

- Prioritize recent metastases: When studying advanced disease, sample metastases rather than primary tumors when feasible, as TME composition differs significantly [27].

- Implement digital pathology: Use automated analysis to quantify cell densities and spatial relationships (e.g., immune cell proximity to cancer cells) across entire tissue sections [23] [27].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive TME Profiling Using Multiplex Immunohistochemistry

Purpose: Simultaneous characterization of multiple immune and stromal cell populations while preserving spatial information.

Materials:

- Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections (3-5 μm)

- Validated antibody panel (e.g., 9-17 markers covering T cells, B cells, myeloid cells, checkpoint markers, structural markers)

- Orion platform or comparable multiplex IHC system

- Image analysis software with cellular neighborhood analysis capability [23]

Method:

- Tissue preparation: Cut sections, deparaffinize, and perform antigen retrieval.

- Staining cycles: For each marker, apply primary antibody, secondary detection, fluorescence-conjugated tyramide signal amplification, and antibody stripping.

- Image acquisition: Scan slides using high-resolution fluorescence scanner.

- Image analysis:

- Segment individual cells based on nuclear and membrane markers

- Assign cell phenotypes based on marker combinations

- Perform spatial cellular graph partitioning to identify cellular neighborhoods

- Calculate cell-cell proximity metrics [23]

Troubleshooting:

- High background: Optimize antibody concentrations and stripping conditions

- Signal loss: Validate antibody compatibility with stripping protocol

- Analysis errors: Manually review a subset of cell classifications for accuracy

Protocol 2: Single-Cell RNA Sequencing to Decipher TME Heterogeneity

Purpose: Deconvolute cellular composition of tumors and identify novel cell subpopulations associated with therapy resistance.

Materials:

- Fresh tumor tissue or properly preserved tissue (RNAlater or snap-frozen)

- Single-cell RNA sequencing platform (10X Genomics, Drop-seq, etc.)

- Cell viability >80% recommended

- Bioinformatics pipeline for scRNA-seq analysis [26] [25]

Method:

- Single-cell suspension: Dissociate tissue using gentle enzymatic digestion (collagenase/hyaluronidase) with minimal processing time.

- Cell sorting: Remove dead cells and debris using flow cytometry or microfluidic devices.

- Library preparation: Use chosen platform to barcode individual cells and prepare sequencing libraries.

- Sequencing: Aim for 50,000 reads per cell as a minimum.

- Bioinformatic analysis:

- Quality control (remove cells with high mitochondrial gene percentage)

- Normalization and integration of multiple samples

- Unsupervised clustering and cell type annotation using canonical markers

- Trajectory inference and differential expression analysis

- Cell-cell communication network inference [26] [25]

Troubleshooting:

- Low cell viability: Optimize dissociation protocol; use viability enhancers

- Doublets: Adjust cell concentration loading; use computational doublet detection

- Batch effects: Include sample multiplexing and use integration algorithms

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for TME Heterogeneity Studies

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplex IHC Panels | 17-plex tumor immune landscape assay (CD3, CD8, CD20, CD68, CD163, PD-1, PD-L1, etc.) | Comprehensive spatial profiling of immune and stromal cells | Requires validated antibody compatibility; specialized imaging platforms [23] |

| Single-Cell Analysis Platforms | 10X Genomics, BD Rhapsody | High-throughput single-cell transcriptomic profiling | Cell viability critical; computational expertise required [26] [25] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | 10X Visium, Nanostring GeoMx | Mapping gene expression to tissue locations | Integration with H&E staining; resolution limitations [25] |

| Preclinical Models | Patient-Derived Organoids, Patient-Derived Xenografts | Drug testing in context preserving some TME features | PDX models lose human stroma over time; organoids lack full TME [22] |

| Computational Tools | TMEtyper, CARD, inferCNV | Deciphering cellular composition from bulk or spatial data | Algorithm selection depends on research question and data type [29] [25] |

Visualizing Key Concepts

Diagram 1: Tumor Microenvironment Heterogeneity and Therapeutic Implications

Diagram 2: Integrated Workflow for TME Heterogeneity Analysis

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) has undergone a significant paradigm shift, from being considered a single disease entity to a malignancy comprising distinct molecular subtypes with unique therapeutic vulnerabilities. This transformation is largely driven by the discovery of lineage-defining transcription factors that orchestrate different transcriptional programs. The current consensus classification system defines four primary subtypes: SCLC-A (ASCL1-dominant), SCLC-N (NEUROD1-dominant), SCLC-P (POU2F3-dominant), and SCLC-I (inflamed) [30] [12] [31].

This classification system provides a critical framework for addressing the profound tumor heterogeneity that characterizes SCLC and enables the development of precision medicine approaches. Understanding these subtypes, their biological drivers, and their dynamic nature is essential for designing effective therapeutic strategies and overcoming treatment resistance [30] [12].

Molecular Subtypes of SCLC

Subtype Characteristics and Prevalence

SCLC subtypes demonstrate distinct transcriptional profiles, cellular origins, and clinical behaviors. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each major subtype.

Table 1: Molecular Subtypes of Small Cell Lung Cancer

| Subtype | Defining Transcription Factor | Approximate Prevalence | Key Characteristics | Cell of Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCLC-A | ASCL1 | ~70% [30] | Neuroendocrine-high; expresses MYCL, SOX2, DLL3, BCL2 [30] | Pulmonary neuroendocrine cells [32] |

| SCLC-N | NEUROD1 | ~15% [30] | Neuroendocrine-high; associated with MYC expression and aggressive phenotype [30] | Pulmonary neuroendocrine cells [32] |

| SCLC-P | POU2F3 | 7-15% [30] | Non-neuroendocrine; tuft cell lineage; expresses SOX9, ASCL2, IGFR1 [30] | Tuft cells [32] |

| SCLC-I | Low ASCL1/NEUROD1/POU2F3; High inflammatory markers [12] | Not firmly established | Non-neuroendocrine; immune-enriched gene signature [12] | Various, including club and AT2 cells [32] |

Detailed Subtype Profiles and Therapeutic Vulnerabilities

Each SCLC subtype possesses unique molecular dependencies that present opportunities for targeted therapeutic intervention.

Table 2: Subtype-Specific Therapeutic Vulnerabilities and Biomarkers

| Subtype | Key Biomarkers | Therapeutic Vulnerabilities | Response to Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCLC-A | ASCL1, DLL3, BCL2, INSM1 [30] [12] | DLL3-targeting agents (e.g., Tarlatamab), BCL2 inhibitors [30] | More responsive to cisplatin; susceptible to ASCL1-targeting approaches [30] [12] |

| SCLC-N | NEUROD1, MYC, AURKA/B, OTX2 [30] | Aurora kinase inhibitors, BET inhibitors [30] | Associated with chemotherapy resistance; Aurora kinase inhibition potential [30] |

| SCLC-P | POU2F3, SOX9, ASCL2, IGFR1 [30] | IGF1R inhibitors, PARP inhibitors (due to DNA repair deficiencies) [30] | Susceptible to IGF1R-targeted therapies and DNA-damaging agents [30] |

| SCLC-I | HLA genes, IFNγ-related genes, immune checkpoints [12] [31] | Immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., anti-PD-L1) [12] | Better response to immunotherapy; greatest benefit from ICB in NE-SCLC-I subset [12] [31] |

Experimental Workflows for SCLC Subtyping

Molecular Subtyping Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for molecular subtyping of SCLC, integrating multiple omics technologies and analytical approaches.

Diagram 1: Comprehensive SCLC molecular subtyping workflow integrating multi-omics data and functional validation.

Key Methodologies for Subtype Identification

Transcriptomic Profiling: Bulk RNA sequencing remains the foundational method for initial subtype classification based on expression of lineage-defining transcription factors (ASCL1, NEUROD1, POU2F3) and inflammatory markers [30] [31]. For studies requiring single-cell resolution, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) is recommended to assess intratumoral heterogeneity and subtype plasticity [12] [31].

Computational Analysis: Apply non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) to RNA-seq data from patient tumors to identify coherent molecular subtypes. This unsupervised approach has been instrumental in defining the SCLC-I subtype based on inflammatory gene signatures [31]. Validate subtype calls using established transcriptional signatures from reference datasets [30] [31].

Experimental Validation: Utilize patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models, cell-derived xenografts (CDXs), and genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) to confirm subtype-specific vulnerabilities and investigate mechanisms of therapy resistance [32] [31]. These models are particularly valuable for studying subtype plasticity and dynamic subtype transitions in response to therapeutic pressure [12] [31].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SCLC Subtype Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Line Models | SCLC-A: H82, H69; SCLC-N: H196, H187; SCLC-P: H2172; SCLC-Y: H1184 [30] [31] | In vitro studies of subtype-specific biology and drug screening |

| Animal Models | Genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs), Patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) [32] [31] | In vivo validation of subtypes and therapeutic efficacy |

| Antibodies for IHC | Anti-ASCL1, Anti-NEUROD1, Anti-POU2F3, Anti-YAP1, Anti-DLL3 [30] [12] | Subtype identification in tissue sections |

| Targeted Inhibitors | BCL-2 inhibitors (Venetoclax), Aurora kinase inhibitors, PARP inhibitors, IGF1R inhibitors [30] | Functional studies of subtype-specific vulnerabilities |

| qPCR Assays | TaqMan assays for ASCL1, NEUROD1, POU2F3, INSM1, DLL3, AURKA, immune markers [30] [12] | Rapid subtype verification and biomarker quantification |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Subtype Classification and Validation Issues

Q: What could cause discordant results between different subtyping methods (e.g., RNA-seq vs. IHC)?

A: Discordant results often stem from technical and biological factors. Technically, IHC requires validated antibodies with confirmed specificity, as some commercial antibodies may lack sufficient validation for SCLC subtypes [31]. Biologically, tumor heterogeneity means small biopsies may not represent the overall subtype composition, and subtype plasticity can lead to shifts in dominant transcription factor expression between sample collection and analysis [12] [31]. For optimal consistency, utilize orthogonal validation methods (e.g., RNA-seq with qPCR confirmation) and analyze multiple tumor regions when possible.

Q: How can I reliably identify the SCLC-I subtype in patient samples?

A: SCLC-I identification requires specific analytical approaches. Use non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) analysis of RNA-seq data rather than relying solely on single-gene markers [31]. Focus on expression of immune-related gene sets, including HLA genes, interferon-stimulated genes, and T-cell markers [12] [31]. Be aware that SCLC-I can be further subdivided into NE-SCLC-I and non-NE-SCLC-I, which may have different therapeutic implications [31].

Addressing Tumor Heterogeneity and Plasticity

Q: How do I account for subtype plasticity in experimental design?

A: Subtype plasticity presents significant challenges that require specific experimental strategies. Implement longitudinal sampling designs to track subtype transitions during disease progression and therapeutic interventions [12] [31]. Utilize single-cell RNA sequencing to identify mixed subtypes within individual tumors and uncover transitional cell states [12] [31]. Employ in vitro models that allow for monitoring of dynamic subtype changes, such as treatment-resistant cell lines or 3D organoid cultures [12].

Q: What methods best capture intratumoral heterogeneity in SCLC?

A: Comprehensive assessment of heterogeneity requires multiple approaches. Single-cell RNA sequencing is the gold standard for resolving cellular heterogeneity and identifying coexisting subtypes within tumors [12]. Multi-region sampling from different anatomical sections of the same tumor provides spatial context for heterogeneity [12]. For functional studies, establish multiple patient-derived models from the same patient to capture different subclones [31].

Technical Considerations for Therapeutic Testing

Q: Why do subtype-specific vulnerabilities identified in preclinical models sometimes fail to translate clinically?

A: Several factors contribute to this translational gap. Tumor plasticity enables subtype switching under therapeutic pressure, leading to rapid resistance [12] [31]. The tumor microenvironment influences therapeutic responses in ways that may not be fully recapitulated in simplified model systems [12]. Additionally, most preclinical models are established from treatment-naïve tumors, while clinical testing often occurs in heavily pretreated patients where different biological rules may apply [31]. To address these issues, test therapies in models that mimic the clinical context, including treatment-resistant models and those with intact microenvironments.

Q: What are the best practices for evaluating combination therapies targeting multiple subtypes?

A: Effective evaluation of combination strategies requires systematic approaches. First, characterize the subtype composition of your models using established transcriptional signatures [30] [31]. Test agents targeting different subtypes (e.g., DLL3-targeting for SCLC-A combined with IGF1R inhibition for SCLC-P) to address heterogeneity [30]. Include sequential treatment schedules in addition to concurrent combinations, as subtype plasticity may require adaptive therapeutic strategies [12] [31]. Finally, utilize in vivo models that maintain tumor heterogeneity to assess population-level responses [31].

Cutting-Edge Tools and Translational Applications for Heterogeneity Characterization

Core Concepts & Technical FAQs

What are the primary technical considerations when designing a single-cell RNA-seq experiment to address tumor heterogeneity?

The key considerations revolve around choosing the appropriate platform based on your research goals, ensuring proper experimental design with biological replicates, and preparing high-quality single-cell suspensions.

Table: Comparison of Major scRNA-seq Methodologies [33]

| Method Type | Throughput | Cost per Cell | Sensitivity | Best For | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate-based | Lowest | Highest | Highest | Smaller, in-depth studies; full-length transcript data. | Labor-intensive workflow; lower throughput. |

| Droplet-based | Highest | Lowest | Lower than plate-based | Large-scale studies (thousands to millions of cells). | Requires specialized microfluidics equipment; doublet formation. |

| Microwell-based | Intermediate | Intermediate | Lower than plate-based | Medium- to large-scale studies; precious samples. | Chip size can limit throughput and increase cost. |

Why are biological replicates mandatory in single-cell studies, and what are the consequences of pseudoreplication?

Biological replicates (multiple independent samples per condition) are essential for robust statistical analysis. Treating individual cells from one sample as independent replicates is a statistical error called "sacrificial pseudoreplication." This confounds variation within a sample with variation between treatment groups, dramatically increasing the false-positive rate for differential expression, which has been reported to reach 0.3-0.8 without proper correction [34]. The recommended solution is "pseudobulking," where read counts are summed or averaged within samples for each cell type before performing traditional bulk RNA-seq differential expression tests [34].

How can I determine if my single-cell suspension is of sufficient quality for sequencing?

An ideal sample has [34]:

- Concentration: 1,000–1,600 cells/μL.

- Viability: >90%.

- Total Cells: A minimum of 100,000–150,000 cells (allows for cell loss during loading and sorting).

- Buffer: PBS with 0.04% BSA, avoiding inhibitors like high concentrations of EDTA.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

I am observing low cell viability in my single-cell suspensions from core needle biopsies. What are potential causes and solutions?

- Cause: Overly aggressive mechanical or enzymatic dissociation can damage cells.

- Solution: Optimize dissociation protocols by using gentle pipetting, shorter incubation times with enzymes, and titrating enzyme concentrations. Consult resources like the Worthington Tissue Dissociation Database for tissue-specific protocols [34].

My scRNA-seq data shows a high proportion of doublets (multiple cells with the same barcode). How can I prevent and identify this?

- Prevention: Load cells at the recommended concentration to minimize the probability of two cells being encapsulated in the same droplet or microwell. For droplet-based systems, the cell load concentration is optimized to reduce doublets while maintaining capture efficiency [33].

- Identification: Use computational doublet detection tools that are standard in analysis packages (e.g., Scrublet, DoubletFinder). For sample multiplexing, a wet-lab method involves labeling cells from different samples with unique lipid-tagged barcodes before pooling. Doublets will contain multiple barcodes and can be bioinformatically identified and removed [34] [33].

My analysis reveals significant batch effects between samples processed on different days. How can this be mitigated?

Incorporate batch-effect correction during experimental design and data analysis. During sample processing, use techniques like combinatorial indexing or sample multiplexing to pool samples early. During computational analysis, use integration tools such as SCVI or Seurat's integration methods, which use sample identity as a covariate to model and remove technical variation while preserving biological differences [35].

Detailed Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: scRNA-seq Analysis of Primary and Metastatic Tumors

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 study investigating ER+ breast cancer, which successfully delineated the tumor microenvironment in unpaired primary and metastatic samples [35].

1. Sample Preparation and Single-Cell Dissociation

- Obtain fresh tumor biopsies from primary and metastatic sites (e.g., liver, bone, lymph nodes).

- Generate a single-cell suspension using a standardized protocol combining mechanical dissociation and enzymatic digestion (e.g., collagenase/hyaluronidase mix).

- Filter the suspension through a 40-μm strainer to remove clumps and debris.

- Resuspend cells in PBS with 0.04% BSA. Assess cell concentration and viability (>90%) using an automated cell counter.

2. Single-Cell Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Use a droplet-based system (e.g., 10x Genomics 3' Gene Expression) following the manufacturer's instructions.

- The system encapsulates single cells in droplets with barcoded beads. mRNA is reverse-transcribed, and the resulting cDNA is amplified and used to prepare sequencing libraries.

- Sequence libraries on an Illumina platform to a sufficient depth (e.g., 50,000 reads per cell).

3. Computational Data Analysis

- Quality Control & Filtering: Remove cells with high mitochondrial gene percentage (indicating stress/death), low unique molecular identifier (UMI) counts, or low gene counts. Remove doublets computationally.

- Normalization & Integration: Normalize gene expression data and use a biology-aware integration tool (e.g., SCANVI) to combine data from multiple samples, correcting for batch effects [35].

- Cell Type Annotation: Perform clustering and annotate cell types (malignant, immune, stromal) using known marker genes [35]. For example:

- Malignant cells: High CNV burden, epithelial markers.

- T cells: Expression of CD3D, CD3E.

- Macrophages: Expression of CD14, CD68, FCGR3A (CD16).

- Fibroblasts: Expression of COL1A1, DCN.

- Copy Number Variation (CNV) Analysis: Use InferCNV or similar tools to infer large-scale chromosomal alterations in malignant cells, using T cells as a diploid reference [35].

- Differential Expression & Cell-Cell Communication: Identify differentially expressed genes between conditions and infer intercellular signaling networks using tools like CellChat.

Diagram Title: scRNA-seq Workflow for Tumor Analysis

Protocol: Integrating Multi-Region Biopsy Data with Liquid Biopsy

Liquid biopsy can complement multi-region and single-cell analyses by providing a non-invasive means to monitor tumor evolution and minimal residual disease (MRD) [36].

1. Sample Collection

- Collect multiple spatially separated tissue biopsies from the primary tumor during resection.

- Collect matched blood samples in cell-free DNA blood collection tubes for plasma separation.

2. Parallel Processing

- Tissue Biopsies: Process as described in the scRNA-seq protocol above.

- Blood Samples: Centrifuge to isolate plasma. Extract cell-free DNA (cfDNA) using a commercial kit.

3. Analysis and Integration

- Tissue: Perform scRNA-seq as described.

- Liquid Biopsy: Analyze cfDNA for MRD using highly sensitive methods like droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) or whole-genome sequencing (WGS). The TOMBOLA trial showed an 82.9% concordance between these methods, with ddPCR offering higher sensitivity in low tumor fraction samples [36].

- Data Integration: Correlate clonal subtypes and TME features identified in tissue with ctDNA dynamics in the blood. The presence of specific mutations in ctDNA can be traced back to subclones found in specific tumor regions.

Key Signaling Pathways in Tumor Heterogeneity and Progression

Single-cell studies have uncovered critical pathways that differ between primary and metastatic sites, revealing potential therapeutic vulnerabilities [35] [12].

Table: Key Signaling Pathways in Tumor Progression

| Pathway | Role in Primary Tumor | Role in Metastasis | Potential Therapeutic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α/NF-κB | Increased activation, potentially pro-inflammatory [35]. | Decreased activation [35]. | Potential target in primary disease. |

| Neuroendocrine Signaling (ASCL1, NEUROD1) | Defines SCLC-A and SCLC-N subtypes [12]. | SCLC-N more prevalent in metastases; subtype switching post-therapy [12]. | Subtype-specific therapies; targeting plasticity. |

| TGF-β Signaling | Associated with non-neuroendocrine subtypes [12]. | Promotes liver metastasis in non-NE SCLC [12]. | Inhibition may prevent metastatic spread. |

Diagram Title: Pathway Dynamics in Metastasis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Experiments

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics 3' Gene Expression Kit | The standard "workhorse" for high-throughput scRNA-seq. Employs polyA-based capture of mRNA at the 3' end, with cell barcodes and UMIs [34]. | Available with feature barcoding for cell surface protein (CITE-seq) or sample multiplexing. |

| Cell Hashtag Oligos (HTOs) | Allows sample multiplexing by labeling cells from different samples with unique barcoded antibodies before pooling. Reduces batch effects and cost [34]. | Enables computational doublet detection and identification. |

| Enzymatic Dissociation Kits | Generate single-cell suspensions from solid tumor tissues. | Critical step; optimize for each tissue type to maximize viability and yield. |

| Viability Staining Dye | Distinguishes live from dead cells during quality control and sorting. | e.g., Propidium Iodide, DAPI, or commercial live/dead stains. |

| Magnetic-activated Cell Sorting (MACS) Kits | For positive or negative selection of specific cell populations prior to sequencing. | Cost-effective method to enrich for target cells (e.g., immune cells) with high purity [37]. |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Applications

Q1: How does ctDNA analysis address the challenge of tumor heterogeneity in a way that tissue biopsies cannot? A tissue biopsy provides a snapshot from a single site and time point, which can miss spatially separated subclones or temporally evolving resistance mechanisms due to intratumoral heterogeneity [38]. In contrast, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is shed from multiple tumor sites throughout the body. Analyzing ctDNA provides a molecular proxy of the overall disease burden, capturing a more comprehensive picture of the genetic landscape, including different subclones, and enabling real-time tracking of clonal evolution [38] [39].

Q2: What is the typical fraction of ctDNA in total cell-free DNA (cfDNA), and how does this impact assay sensitivity? The fraction of ctDNA in total cfDNA is often very low, typically ranging from 0.01% to over 90%, with levels correlating with tumor stage and burden [38]. In early-stage cancers, the fraction can be at or below 0.1%, posing a significant challenge for detection [39]. This low variant allele frequency (VAF) is the primary reason why highly sensitive techniques like digital PCR or next-generation sequencing (NGS) are required to distinguish tumor-derived mutations from background noise and polymerase errors [38].

Q3: What are the key clinical applications of tracking clonal evolution via ctDNA? The primary applications include:

- Monitoring Treatment Response: Serial ctDNA quantification can track tumor dynamics in real time, often correlating with treatment efficacy [38].

- Identifying Resistance Mechanisms: Detecting the emergence of new mutations (e.g., EGFR T790M in NSCLC) that confer resistance to targeted therapies [38] [40].

- Assessing Minimal Residual Disease (MRD): Detecting ctDNA after curative-intent surgery can predict clinical relapse months before radiographic evidence appears [41] [40].

- Capturing Tumor Heterogeneity: Providing a composite view of the genetic alterations across all tumor sites in a patient [38].

Experimental Protocols for Tracking Clonal Evolution

Protocol: Longitudinal ctDNA Sampling and NGS Analysis

Objective: To monitor the temporal dynamics of tumor subclones during therapy using a targeted NGS panel.

Materials:

- Blood collection tubes (e.g., K₂EDTA or dedicated cfDNA tubes)

- DNA extraction kit for plasma cfDNA

- Targeted NGS panel for cancer-relevant genes

- Library preparation and sequencing platform

- Bioinformatic pipeline for variant calling and clonal tracking

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Collect longitudinal blood samples (e.g., at diagnosis, before each treatment cycle, at suspected progression). Process plasma within 2-4 hours of collection to prevent leukocyte lysis and contamination of cfDNA with genomic DNA [39].

- cfDNA Extraction: Isolate cfDNA from 1-4 mL of plasma using a silica-membrane or magnetic bead-based kit. Quantify yield using a fluorometer.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Construct sequencing libraries from the extracted cfDNA.

- Use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to tag original DNA molecules, which is critical for error correction and accurate quantification of low-frequency variants [38].

- Enrich target regions using a hybrid-capture or amplicon-based panel covering key cancer genes.

- Sequence on an NGS platform to a high depth (e.g., >10,000x coverage) to ensure sensitivity for variants with low VAF [38].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Variant Calling: Identify somatic mutations (SNVs, indels) against a reference genome, using UMI-aware algorithms to filter sequencing artifacts.

- Variant Quantification: Calculate the VAF for each mutation (VAF = [Alternate reads / Total reads] * 100).

- Clonal Tracking: Plot the VAF of specific mutations over time. The rise or fall of distinct mutations provides evidence of clonal evolution and subpopulation dynamics in response to therapeutic pressure.

Protocol: Assessing Tumor Heterogeneity via ctDNA

This protocol extends the basic NGS analysis to specifically evaluate heterogeneity.

Methodology:

- Deep Sequencing and Mutation Identification: Follow steps 1-4 of the previous protocol to establish a baseline mutation profile from a pre-treatment plasma sample.

- Clustering of Mutations: Group mutations based on their VAFs. Mutations with similar VAFs are likely to originate from the same subclone.

- Phylogenetic Inference: Use computational tools to reconstruct the evolutionary relationships between the identified subclones, inferring ancestral and descendant clones.

- Longitudinal Monitoring: Track the VAFs of these subclone-specific mutations across subsequent time points. The expansion of a minor clone with a specific resistance mutation indicates the emergence of a resistant subpopulation.

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for analyzing clonal evolution from ctDNA.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Low ctDNA Yield or Fraction

Problem: High Background Noise Obscuring Low-Frequency Variants

- Potential Cause: Sequencing errors, PCR artifacts, or white blood cell lysis contributing germline variants to cfDNA [38].

- Solutions:

- Implement a unique molecular identifier (UMI) strategy to tag and bioinformatically collapse PCR duplicates, correcting for errors [38].

- Sequence a matched peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) sample to identify and filter out clonal hematopoiesis variants.

- Use robust bioinformatic pipelines designed for low-VAF variant calling.

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Technical Replicates

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent sample handling, DNA extraction, or library preparation.

- Solutions:

- Standardize the blood collection and plasma processing protocol across all samples.

- Use a cfDNA extraction kit with high and reproducible recovery.

- Include control samples (e.g., synthetic cfDNA spikes with known mutations) in each batch to monitor technical performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ctDNA-based Clonal Evolution Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| cfDNA Blood Collection Tubes | Stabilizes nucleated blood cells to prevent genomic DNA contamination during sample transport. | Critical for multi-center studies; enables longer sample transit times [39]. |

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | Silica-membrane or magnetic bead-based isolation of cell-free DNA from plasma. | Prioritize kits with high recovery efficiency for low-concentration samples [41]. |

| UID/UMI Adapters | Oligonucleotide tags that uniquely label each original DNA molecule prior to PCR amplification. | Essential for distinguishing true low-frequency variants from PCR and sequencing errors [38]. |

| Targeted NGS Panels | Probe sets for hybrid-capture or amplicon-based enrichment of cancer-associated genes. | Panels should cover genes relevant to the cancer type and known resistance mechanisms [38]. |

| Digital PCR Assays | Absolute quantification of specific mutations by partitioning a sample into thousands of individual reactions. | Useful for ultra-sensitive validation and longitudinal tracking of known mutations [38] [39]. |

The following diagram maps the relationship between tumor heterogeneity, ctDNA shedding, and the resulting clinical applications that inform treatment strategies.

Radiomics and Imaging Heterogeneity Quantification as Non-Invasive Biomarkers

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is radiomics and how does it relate to tumor heterogeneity? A1: Radiomics is an emerging field of study that involves the extraction of high-dimensional, quantitative data from medical images to discover associations with pathological findings, genomic data, or clinical endpoints like diagnosis, prognosis, and prediction of treatment response [42]. It utilizes millions of voxels from multi-section tomographic or volumetric imaging data, which comprehensively represent biological information regarding a disease [42]. A key benefit is that high-dimensional radiomic data provide insight into intra-tumoral heterogeneity by identifying sub-regions and reflecting the spatial complexity of a disease, which is especially promising for personalized medicine in oncology [42].

Q2: What are the main steps in a standard radiomics pipeline? A2: The standard radiomics workflow, or pipeline, consists of several sequential steps [42]:

- Image Acquisition: Obtaining digitalized imaging data (e.g., CT, MRI, PET).

- Pre-processing: Standardizing images through registration and signal intensity normalization to ensure reproducibility.

- Region of Interest (ROI) Definition: Segmenting the tumor, often semi-automatically with software like 3D-Slicer.

- Feature Extraction: Calculating a large number of quantitative features from the segmented volume.

- Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction: Reducing false positives by selecting the most relevant features from the high-dimensional data.

- Classifier Modeling and Validation: Building statistical models to find associations with patient outcomes and validating them on independent datasets.

Q3: What types of features are extracted in a radiomics analysis? A3: There are two main types of features [42]:

- Semantic Features: Qualitative descriptors familiar to radiologists, such as size, shape, location, and the presence of necrosis (e.g., VASARI features for gliomas).

- Agnostic Features: Quantitative, mathematically extracted descriptors. These are further categorized into:

- Morphologic features: Describe the 3D geometric properties of a tumor (e.g., volume, sphericity, surface-to-volume ratio).

- Statistical features: Include first-order statistics (from intensity histograms, e.g., mean, entropy, kurtosis) and second-order or texture features (e.g., from Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix - GLCM) that retain spatial information about pixel relationships [42] [43].

- Transform-based methods: Features derived from applying filters or transforms, such as Wavelet transformations [42].

Q4: Why is quantifying imaging heterogeneity important for treatment strategies? A4: Tumors are often inhomogeneous, containing subpopulations of cells with different genotypes and phenotypes that may differ in sensitivity to treatments [43]. Quantifying this heterogeneity via imaging provides a non-invasive biomarker for [43]:

- Tumor Characterization: Differentiating between tumor types and grading.

- Outcome Prediction: Providing prognostic information.

- Treatment Monitoring: Assessing response to therapy. For instance, the existence of poorly vascularized or hypoxic areas within a tumor correlates with treatment failure for radiotherapy and chemotherapy [43]. This knowledge can guide strategies like dose escalation to resistant sub-regions [43].