ddPCR for Rare Mutation Detection: A Comprehensive Guide for Precision Oncology and Biomarker Research

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) has emerged as a powerful technology for the precise detection and absolute quantification of rare mutations, revolutionizing applications in liquid biopsies, cancer monitoring, and disease research.

ddPCR for Rare Mutation Detection: A Comprehensive Guide for Precision Oncology and Biomarker Research

Abstract

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) has emerged as a powerful technology for the precise detection and absolute quantification of rare mutations, revolutionizing applications in liquid biopsies, cancer monitoring, and disease research. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of ddPCR, its core methodology and diverse applications in detecting circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and monitoring treatment response, practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and a critical validation against other technologies like qPCR and NGS. By synthesizing the latest evidence and future directions, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to leverage ddPCR's high sensitivity and reproducibility for advancing precision medicine.

The Power of Precision: Understanding ddPCR and Its Role in Rare Mutation Analysis

Digital PCR (dPCR) represents a paradigm shift in nucleic acid quantification, moving from the relative measurements of its predecessors to a calibration-free method of absolute quantification. This capability is particularly transformative for detecting rare mutations in cancer research and drug development, where sensitivity and precision are paramount [1] [2]. This guide details the core technical principles of dPCR, from sample partitioning to final calculation, framing them within the context of advanced research applications.

The Evolution of PCR: From qPCR to Digital Absolute Quantification

The journey to dPCR began with conventional Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), an endpoint method that provides semi-quantitative information. The development of quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) introduced relative quantification by monitoring amplification in real-time and comparing results to a standard curve [1] [2]. However, qPCR's reliance on calibration curves makes it susceptible to efficiency variations, impacting accuracy and reproducibility [2].

Digital PCR addresses these limitations by redefining the approach to measurement. The foundational concept—partitioning a sample to isolate individual molecules—was explored in the 1990s and early 2000s using limiting dilutions in multi-well plates [1]. The term "digital PCR" was coined in 1999 by Bert Vogelstein's team, who used this method to detect cancer mutations [1] [3]. Subsequent advancements in microfluidics enabled the practical partitioning of samples into thousands to millions of nanoliter- or picoliter-scale reactions, leading to the modern dPCR platforms widely used today [1] [3].

The table below summarizes the key distinctions between qPCR and dPCR.

Table: Fundamental Differences Between qPCR and dPCR

| Feature | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Digital PCR (dPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Basis | Relative to a standard curve | Absolute, based on Poisson statistics |

| Calibration | Requires calibration curve | Calibration-free |

| Measurement Type | Real-time (kinetic) | End-point |

| Signal Output | Continuous (Ct value) | Digital (positive/negative partition count) |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | Lower | Higher [2] |

| Ideal Application | High-abundance target quantification | Rare event detection, absolute copy number [4] |

Core Technical Principles of dPCR

The power of dPCR stems from a simple yet powerful workflow that converts a continuous analog signal into a discrete digital one.

The Four-Step Workflow

The dPCR process can be broken down into four key steps:

- Partitioning: The PCR reaction mixture—containing the sample, primers, probes, mastermix, and enzymes—is randomly partitioned into a large number of individual reactions [1] [3]. Two main partitioning methods are used:

- Amplification: The partitioned samples undergo standard PCR thermal cycling. Partitions containing at least one copy of the target sequence will amplify it exponentially, while those without a target will not [2].

- End-point Fluorescence Analysis: After amplification, each partition is analyzed for fluorescence. In a probe-based assay, a fluorescent signal indicates a "positive" partition, while no signal indicates a "negative" partition [1] [2].

- Absolute Quantification using Poisson Statistics: The ratio of positive to total partitions is used to calculate the absolute concentration of the target in the original sample, applying Poisson statistics to account for the random distribution of molecules [1] [2].

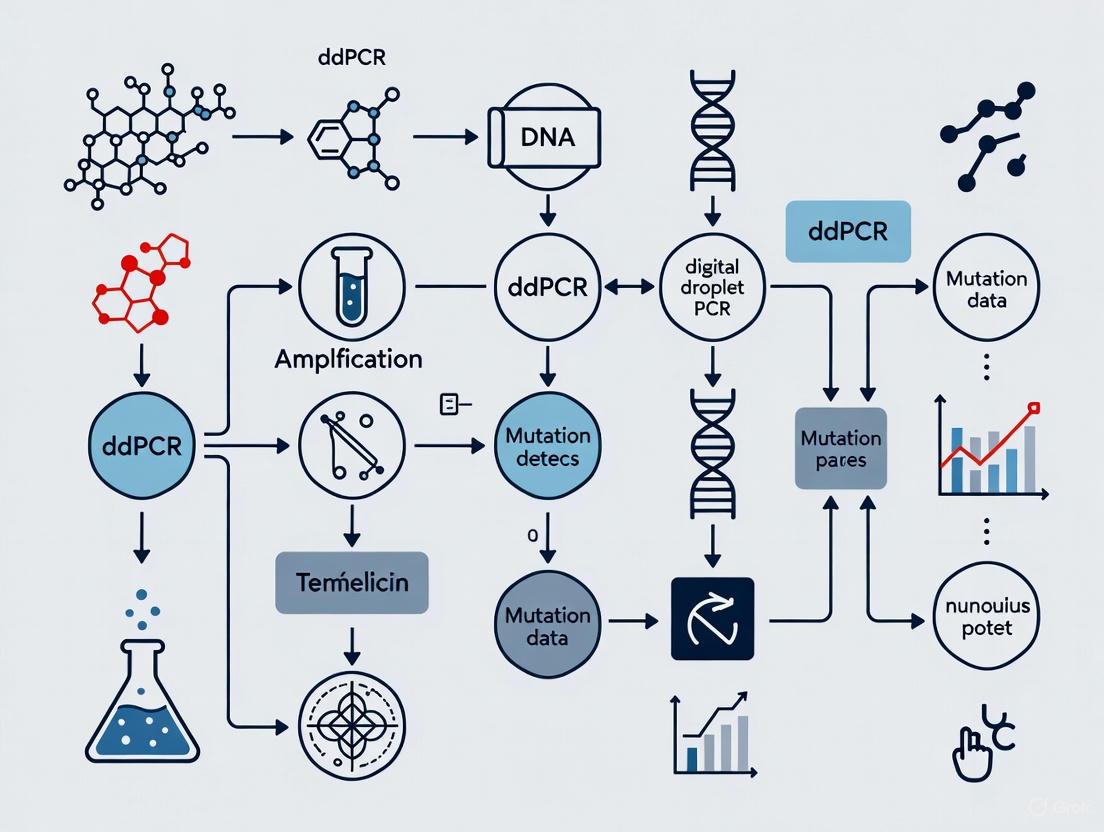

Diagram: The Core dPCR Workflow

The Statistical Foundation: Poisson Distribution

The absolute quantification in dPCR hinges on the fact that the distribution of target molecules across many partitions follows a Poisson distribution. This statistical model accounts for the randomness of the distribution, ensuring that some partitions will contain more than one target molecule, while others will contain none [2].

The fundamental formula for calculating the average number of target molecules per partition (λ) is: λ = -ln(1 - p) where p is the proportion of positive partitions (p = number of positive / total number of partitions) [2].

The absolute concentration in the original sample is then calculated as: Concentration = λ / (Partition Volume × Number of Partitions)

The precision of this measurement is intrinsically linked to the total number of partitions analyzed. A higher number of partitions yields a more precise and confident measurement, which is critical for detecting low-frequency mutations [4] [2]. The confidence interval for the estimated concentration can be determined using statistical methods like the Wilson score interval, which is preferred for its accuracy across all values of p [2].

A Practical Guide for Rare Mutation Detection

The following section provides a detailed experimental protocol for detecting a rare mutation, using the EGFR T790M mutation in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) as a model. This mutation confers resistance to first-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and its early detection is crucial for guiding treatment [4].

Assay and Experimental Design

- Assay Configuration: For rare mutation detection, a duplex probe-based assay is typically used. A single set of primers amplifies the region of interest. Two hydrolysis probes (e.g., TaqMan), each labeled with a different fluorophore, are used: one specific to the wild-type sequence and the other specific to the mutant allele [4].

- DNA Input and Sensitivity Calculation: Accurate DNA quantification is vital. The amount of input DNA directly determines the theoretical limit of detection (LOD) for the rare allele. For human genomic DNA, the number of copies can be calculated as: Number of copies = mass of DNA (in ng) / 0.003 (where 0.003 ng is the approximate mass of a single haploid human genome) [4].

- The theoretical sensitivity can be calculated as: Sensitivity = (Theoretical LOD of the system in copies/μL) / (Total concentration of target copies in the sample in copies/μL). For example, with 10 ng of human genomic DNA and a system LOD of 0.2 copies/μL, the theoretical sensitivity for detecting a mutant allele is approximately 0.15% [4].

Step-by-Step Protocol: EGFR T790M Detection

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for ddPCR

| Reagent / Component | Function / Description | Example Final Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| dPCR Mastermix | Provides DNA polymerase, dNTPs, reaction buffer, and MgCl₂. | 1X |

| Primer Set | Forward and reverse primers flanking the EGFR T790 locus. | 500 nM each [4] |

| Wild-Type Probe | Hydrolysis probe binding to the wild-type EGFR sequence. Labeled with fluorophore 1 (e.g., FAM). | 250 nM [4] |

| Mutant Probe | Hydrolysis probe binding to the mutant EGFR T790M sequence. Labeled with fluorophore 2 (e.g., Cy3). | 250 nM [4] |

| Reference Dye | Passive dye for normalization; required by some instruments. | As per manufacturer |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent to achieve the final reaction volume. | - |

- PCR Mix Preparation: In a nuclease-free tube, assemble the reaction mixture according to the table above. Include necessary controls: a Non-Template Control (NTC), and monocolor controls for each probe to correct for fluorescence spillover [4].

- Partitioning: Load the PCR mix into the dedicated consumable of your dPCR system (e.g., a cartridge or chip) and perform the partitioning according to the manufacturer's protocol [4].

- Thermal Cycling: Transfer the partitions to a thermal cycler and run the following program, optimized for the EGFR T790M assay:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes (1 cycle)

- Amplification: 95°C for 30 seconds, then 62°C for 15 seconds (45 cycles) [4]

- Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Read the partitions using your dPCR system's analyzer (either by planar imaging or in-line detection) [4].

- Apply a compensation matrix to correct for fluorescence spillover between channels if necessary [4].

- The software will automatically apply Poisson statistics to calculate the absolute concentration of both wild-type and mutant sequences in copies/μL. The mutant allelic frequency is then given by: (Mutant concentration / (Mutant + Wild-type concentration)) × 100.

Diagram: Rare Mutation Detection Logic

Advanced Applications in Research and Drug Development

The unique advantages of dPCR make it indispensable in modern biomedical research.

- Oncology and Liquid Biopsy: dPCR is exceptionally suited for analyzing circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) from liquid biopsies. It can monitor treatment response by tracking the rise or fall of specific mutations and detect the emergence of resistance mutations (like EGFR T790M) with high sensitivity, enabling timely therapy switches [1] [5].

- Infectious Disease and Viral Load Monitoring: dPCR provides absolute quantification of pathogen load without standard curves, proving valuable for monitoring low-level persistent infections like HIV and for the precise detection of antibiotic-resistance genes in bacteria [1].

- Gene Therapy and Vector QC: In AAV-based gene therapy development, dPCR kits (e.g., VeriCheck) are used to precisely measure the titer of full versus empty viral capsids, a critical quality attribute that impacts therapeutic efficacy and safety [6].

- Mutation Scanning: Advanced techniques like COLD-ddPCR combine dPCR with co-amplification at lower denaturation temperature PCR. This method uses two wild-type probes with different fluorophores; a mutation anywhere under either probe causes a deviation in the FAM/HEX ratio, enabling scanning for unknown mutations within a target region [5].

Table: Commercial dPCR Platforms (Representative Examples)

| Brand | Instrument | Partitioning Method | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermo Fisher Scientific | QuantStudio Absolute Q | Microchambers | Microfluidic Array Plate (MAP) with up to 20,480 partitions per sample [1]. |

| Bio-Rad Laboratories | QX Continuum ddPCR System | Droplets | Droplet-based system for a wide range of applications; for research use only [7]. |

| Qiagen | QIAcuity | Microchambers | Integrated instrument for partitioning, amplification, and imaging [1]. |

Digital PCR's core principle of partitioning samples for absolute, calibration-free quantification represents a significant advancement in molecular analysis. By combining physical partitioning with robust Poisson statistics, it provides researchers and drug developers with a tool of exceptional sensitivity and precision. As the technology continues to evolve with more integrated platforms and novel assays, its role in pushing the boundaries of rare mutation detection, disease monitoring, and advanced therapy development is set to expand further.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) represents one of the most transformative technologies in molecular biology, enabling exponential amplification of specific DNA sequences. From its inception as a qualitative tool, PCR technology has evolved through generations that progressively enhanced its quantitative capabilities. This evolution culminated in digital PCR (dPCR), a third-generation technology that provides absolute quantification of nucleic acids without requiring standard curves [3]. For researchers in rare mutation detection, this technological progression has been crucial, as it has steadily improved the sensitivity, accuracy, and precision required to identify genetic variants present in minute quantities within complex biological samples.

The journey from conventional PCR to digital PCR reflects a fundamental shift from relative to absolute quantification, with particular significance for applications like liquid biopsies, cancer biomarker detection, and monitoring minimal residual disease. This article traces the historical development, technical milestones, and practical implications of this evolution, with special emphasis on its critical role in advancing rare mutation research.

The Historical Progression of PCR Technologies

Conventional PCR: The Foundation of DNA Amplification

Conventional PCR, pioneered by Kary Mullis in 1986, revolutionized molecular biology by allowing specific DNA sequences to be amplified exponentially through repeated thermal cycling [3]. The fundamental process consists of three main steps per cycle: denaturation (separating DNA strands), annealing (binding primers to target sequences), and extension (synthesizing new DNA strands). This process relies on essential components including synthetic oligonucleotide primers, a thermostable DNA polymerase enzyme, and deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate monomers (dNTPs) [3].

Despite its revolutionary impact, conventional PCR presented significant limitations:

- End-point detection: Analysis occurred after all amplification cycles were complete, typically using gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining to visualize amplified products [8]

- Semi-quantitative nature: Results were based on band intensity, providing only approximate quantification [3]

- Limited dynamic range: Detection relied on post-amplification processing, restricting accurate quantification [8]

- Low sensitivity: Difficulty detecting rare mutations in a background of wild-type sequences

These limitations restricted conventional PCR primarily to qualitative applications, such as confirming the presence or absence of specific DNA sequences, with limited utility for precise quantification needed in research and clinical diagnostics.

Quantitative PCR: Introducing Real-Time Monitoring

The development of quantitative PCR (qPCR), also known as real-time PCR, in 1992 by Russell Higuchi addressed several limitations of conventional PCR by enabling monitoring of amplification progress as it occurred [3]. This second-generation PCR technology incorporated fluorescent detection systems—either DNA-intercalating dyes like SYBR Green or sequence-specific fluorescent probes (TaqMan probes)—to track DNA accumulation during each cycle [8].

The key innovation of qPCR was the introduction of the threshold cycle (Cт) value, defined as the PCR cycle number at which the fluorescence signal crosses a predetermined threshold above background levels [8]. This value correlates inversely with the starting quantity of the target nucleic acid, enabling relative quantification when compared to standards of known concentration [9].

qPCR offered significant advantages over conventional PCR:

- Generation of quantitative data: Enabled measurement of DNA concentration across a wide dynamic range [8]

- Increased sensitivity: Capable of detecting down to a single copy of the target sequence [8]

- Elimination of post-PCR processing: Reduced hands-on time and contamination risk [8]

- Higher throughput capabilities: Allowed screening of more samples in less time

However, qPCR maintained important limitations, particularly its dependence on standard curves for quantification and susceptibility to amplification efficiency variations caused by PCR inhibitors [10]. These constraints motivated the development of more precise quantification technologies.

Digital PCR: Absolute Quantification at the Single-Molecule Level

Digital PCR (dPCR) represents the third generation of PCR technology, fundamentally changing the approach to nucleic acid quantification. The conceptual foundation for dPCR was established in 1992 when Morley and Sykes combined limiting dilution PCR with Poisson statistics to isolate, detect, and quantify single nucleic acid molecules [3]. In this pioneering work, the authors successfully detected mutated IgH rearranged heavy chain genes at frequencies as low as 2 targets in 160,000 wild-type sequences within bone marrow samples from leukemia patients [3].

The term "digital PCR" was formally coined in 1999 by Bert Vogelstein and colleagues, who developed a workflow using limiting dilution distributed across 96-well plates combined with fluorescence readout to detect RAS oncogene mutations in stool samples from colorectal cancer patients [3]. This milestone publication established the core principle of dPCR: partitioning a sample into many individual reactions such that each contains either zero or one (or a few) target molecules, followed by amplification and binary scoring of each partition as positive or negative for the target [3].

The period from 1999 to 2006 saw critical refinements to dPCR technology. In 2003, Vogelstein's group introduced the BEAMing technology (Beads, Emulsion, Amplification, and Magnetics), which simplified compartmentalization using water-in-oil droplets [3]. This approach involved encapsulating individual DNA molecules with magnetic beads coated with primers, permitting PCR amplification within droplets, with subsequent analysis by flow cytometry. This methodology significantly advanced rare mutation detection capabilities.

Technical Principles and Methodological Advances

Fundamental Working Principle of Digital PCR

Modern dPCR protocols follow four essential steps that enable absolute quantification of nucleic acids. The process begins with sample partitioning, where the PCR mixture containing the sample is distributed across thousands to millions of separate compartments [3]. This step relies on random distribution of target molecules among partitions according to Poisson statistics. The second step involves amplifying target molecules within each partition through conventional PCR thermal cycling. Unlike qPCR, which monitors amplification in real-time, dPCR uses end-point fluorescence detection as its third step, analyzing each partition after amplification is complete [3]. The final step applies Poisson statistical analysis to the ratio of positive to negative partitions, calculating the absolute concentration of the target nucleic acid in the original sample without requiring standard curves [3].

The mathematical foundation of dPCR relies on Poisson distribution statistics, which describe the probability of a target molecule being present in any given partition. The formula for calculating target concentration is:

[ \text{Concentration} = -\ln(1 - p) / V ]

Where "p" represents the proportion of positive partitions, and "V" is the volume of each partition. This approach enables absolute quantification, as the calculation depends only on the binary readout of each partition and the known partition volume.

Partitioning Methodologies: Droplet vs. Chip-Based Systems

Two primary partitioning methodologies have emerged in dPCR platforms, each with distinct advantages and applications:

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) utilizes a water-oil emulsion system to create thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets, typically generating 20,000 or more partitions per sample [11]. The process involves microfluidic chips that leverage passive or active forces to break the aqueous/oil interface at high speeds (1-100 kHz) [3]. A critical consideration in ddPCR is droplet stability during thermal cycling, which requires appropriate surfactants to prevent coalescence, especially during temperature variations [3]. Bio-Rad's QX200/QX600/QX700 systems represent commercially successful implementations of this technology [11].

Chip-Based dPCR employs fixed arrays of microscopic wells or chambers embedded in solid chips. Examples include Applied Biosystems' AbsoluteQ system with approximately 20,000 fixed microwells and QIAGEN's QIAcuity system using nanoplates with similar partition counts [11]. This approach offers higher reproducibility and easier automation but is typically limited by fixed partition numbers and higher costs per run compared to droplet-based systems [3].

Detection and Analysis Systems

dPCR platforms utilize two primary readout methodologies for analyzing partitions. In-line detection, commonly used in ddPCR systems, involves flowing droplets sequentially through a microfluidic channel or capillary past a detection system consisting of a light source coupled with fluorescence detectors [3]. This approach allows analysis of a large number of droplets but requires precise flow control. Alternatively, planar imaging systems capture static snapshots of microchambers or microdroplets using fluorescence microscopy or scanning technologies [3]. Recent advances include 3D imaging and analysis techniques that enable faster assessment of larger numbers of droplets within reduced timeframes [3].

Comparative Analysis of PCR Generations

Technical Performance Comparison

The evolution from conventional PCR to qPCR and finally to dPCR has resulted in progressive improvements in key performance metrics, particularly for demanding applications like rare mutation detection.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of PCR Technologies

| Parameter | Conventional PCR | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Digital PCR (dPCR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification Approach | Semi-quantitative (end-point) | Relative (requires standard curve) | Absolute (no standard curve) |

| Detection Method | Gel electrophoresis | Real-time fluorescence | End-point fluorescence |

| Sensitivity | Low | Moderate (can detect single copies) | High (detects rare mutations <0.1%) |

| Precision | Low | Moderate | High (CV < 10% common) |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | Low | Moderate | High |

| Dynamic Range | Limited | 5-6 logs | 5 logs |

| Multiplexing Capability | Limited | Moderate | High (4-12 targets) |

Practical Workflow Comparison

The practical implementation of these technologies differs significantly in hands-on time, equipment requirements, and analytical workflows.

Table 2: Workflow Comparison Between dPCR and ddPCR

| Parameter | Chip-Based dPCR | Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Partitioning Mechanism | Fixed array/nanoplate | Emulsion droplets |

| Time to Results | < 90 minutes | 6-8 hours (multiple steps) |

| Multiplexing Capability | Available for 4-12 targets | Limited (newer models up to 12 targets) |

| Ease of Use | Integrated automated system | Multiple steps and instruments |

| Ideal Environment | QC and clinical settings | Research and development labs |

| Throughput | High | Moderate |

Experimental Protocols for Rare Mutation Detection

Sample Preparation and DNA Isolation

Effective rare mutation detection begins with optimal sample preparation. For liquid biopsy applications, blood samples should be collected in cell-stabilization tubes to prevent genomic DNA release from nucleated blood cells. Plasma separation via centrifugation (800-1600 × g for 10 minutes) should occur within 6 hours of collection, followed by a second centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove residual cells [12]. DNA extraction can be performed using commercially available kits optimized for cell-free DNA recovery, such as the MagMax Viral/Pathogen kit used with KingFisher Flex automated extraction systems [10]. DNA quantification should use fluorescence-based methods rather than UV spectrophotometry, as the latter lacks sensitivity for low-concentration cell-free DNA samples.

Assay Design Considerations

Effective dPCR assays for rare mutation detection require careful design to maximize specificity and sensitivity. Key considerations include:

- Amplicon Length: Shorter amplicons (60-100 bp) are preferred for fragmented DNA sources like formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue or cell-free DNA

- Probe Design: Dual-labeled hydrolysis probes (TaqMan-style) should be designed with the variant nucleotide positioned centrally in the probe sequence to maximize discrimination

- Primer Placement: Primers should flank the target mutation with their 3' ends positioned to minimize mispriming to homologous sequences

- Validation: Assays should be validated using synthetic oligonucleotides or cell lines with known mutation status to establish limit of detection and limit of quantification

dPCR Setup and Optimization

For rare mutation detection, reaction setup must be optimized to maximize the number of partitions while maintaining amplification efficiency. A typical 20μL reaction mixture contains:

- 1× dPCR master mix

- 900 nM forward and reverse primers

- 250 nM wild-type and mutation-specific probes

- 5-50 ng DNA template

- Nuclease-free water to volume

Probe-based assays should utilize different fluorescent dyes (FAM, HEX/VIC, CY5) with non-overlapping emission spectra for wild-type and mutation-specific probes. Appropriate negative controls (no-template controls) and positive controls (synthetic oligonucleotides with known mutation status) must be included in each run.

Partitioning follows reaction setup, with methods varying by platform. For droplet-based systems, cartridges generate approximately 20,000 droplets per sample, while chip-based systems use pre-formed wells. Following partitioning, PCR amplification proceeds with standard thermal cycling conditions, though extension times may be optimized based on amplicon length.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Post-amplification analysis involves several critical steps. First, fluorescence data from each partition is collected, typically using a two-dimensional plot of fluorescence amplitudes for each channel. Second, clusters corresponding to different populations (wild-type-only, mutation-only, double-positive, negative) are identified using appropriate gating strategies. For rare mutation detection, the threshold for mutant-positive partitions should be established using negative controls to determine background signals.

The concentration of mutant and wild-type targets is calculated using Poisson statistics applied to the fraction of positive partitions. The variant allele frequency (VAF) is then determined as:

[ \text{VAF} = \frac{[\text{Mutant}]}{[\text{Mutant}] + [\text{Wild-type}]} \times 100\% ]

The limit of detection for rare variants depends on the total number of partitions analyzed. With 20,000 partitions, typical sensitivity reaches 0.1% VAF, while higher partition numbers (100,000+) can achieve 0.01% sensitivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful dPCR experimentation requires specific reagents optimized for partitioning and amplification. The following table outlines essential components and their functions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for dPCR

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| dPCR Master Mixes | ddPCR Supermix, QIAcuity PCR Master Mix | Provides DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer | Optimized for partition stability and efficient amplification |

| Fluorescent Probes | TaqMan probes, Double-stranded DNA binding dyes | Target-specific detection | FAM/HEX/CY5 dyes for multiplexing |

| Partitioning Reagents | Droplet Generation Oil, Nanoplate Reagents | Create stable partitions | Platform-specific formulations |

| DNA Extraction Kits | MagMax Viral/Pathogen Kit | Nucleic acid purification | Optimized for yield and inhibitor removal |

| Assay Design Tools | Custom TaqMan Assay Design Tool | Primer/probe design | Ensures specificity and efficiency |

Commercial dPCR Platforms

The dPCR landscape includes several commercial platforms implementing different partitioning and detection technologies:

- Bio-Rad ddPCR Systems: QX200, QX600, and QX700 systems utilizing droplet technology with 2-6 color detection capabilities [11]

- QIAGEN QIAcuity: Integrated nanoplate-based system with 4-5 plex capability and automated workflow [11]

- Thermo Fisher Absolute Q: Chip-based system with automated analysis and 4-color detection [11]

- RainDrop Systems: High-partition-count droplet systems generating millions of partitions per sample

Platform selection depends on application needs, with droplet-based systems typically offering higher partition counts and chip-based systems providing more streamlined, automated workflows better suited for clinical quality control environments [11].

Application in Rare Mutation Detection Research

Minimal Residual Disease Monitoring

dPCR has demonstrated superior performance for minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring in hematological malignancies. A blinded prospective study comparing dPCR with qPCR in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) demonstrated that dPCR significantly outperformed qPCR, with a better quantitative limit of detection and sensitivity [13]. The number of critical MRD estimates below the quantitative limit was reduced by sixfold in retrospective cohorts and threefold in prospective cohorts when using dPCR compared to qPCR [13]. Furthermore, concordance between dPCR and flow cytometry (another absolute quantification method) was higher than between dPCR and qPCR, likely because both dPCR and flow cytometry provide absolute quantification independent of diagnostic samples [13].

Cancer Liquid Biopsy Applications

In liquid biopsy applications, dPCR enables non-invasive monitoring of tumor-associated mutations in cell-free DNA. The technology's high sensitivity allows detection of cancer-derived DNA fragments present at very low frequencies in blood samples. This capability has proven valuable for treatment response monitoring, resistance mutation detection, and cancer recurrence surveillance. dPCR's absolute quantification provides more reliable tracking of mutation levels over time compared to relative quantification methods, enabling more accurate assessment of disease progression or treatment response.

Analysis of DNA Methylation Patterns

dPCR has also been adapted for DNA methylation analysis, providing sensitive quantification of epigenetic markers. A comparison between ddPCR and qPCR for assessing T-cell proportions via CD3Z promoter methylation status demonstrated that ddPCR exhibited significantly better reproducibility (3.5% coefficient of variation) compared to qPCR (25% coefficient of variation) [14]. Both technologies correlated with flow cytometry measurements, but statistical measures of agreement showed linear concordance was stronger for ddPCR, with absolute values closer to flow cytometry results [14]. This enhanced precision makes dPCR particularly valuable for methylation-based biomarker applications.

Visualizing the Evolution: A Technical Workflow

Diagram 1: Technological Evolution from Conventional PCR to Digital PCR

The evolution from conventional PCR to digital PCR represents a paradigm shift in nucleic acid quantification, moving from qualitative detection to absolute single-molecule counting. For rare mutation detection research, this progression has been particularly significant, enabling applications previously limited by technical constraints. dPCR's ability to provide absolute quantification without standard curves, combined with exceptional sensitivity and precision, has established it as the technology of choice for challenging detection scenarios including minimal residual disease monitoring, liquid biopsy applications, and rare allele detection in heterogeneous samples.

Current trends suggest continued refinement of dPCR technologies, with emphasis on increasing partition density, enhancing multiplexing capabilities, and improving workflow automation. Integration of dPCR with microfluidic systems and development of novel detection chemistries promise to further expand applications in both research and clinical diagnostics. As these advancements continue, dPCR is poised to remain at the forefront of nucleic acid analysis, providing researchers with increasingly powerful tools to address complex biological questions and clinical challenges in rare mutation detection and beyond.

Rare mutations, defined as genetic variants present at very low frequencies within a cellular population or biological sample, hold profound clinical significance in oncology and genetic diseases. The ability to detect these mutations is critical for early cancer diagnosis, monitoring minimal residual disease (MRD), assessing tumor heterogeneity, and enabling personalized treatment strategies [3]. In non-cancerous genetic disorders, detecting rare mutations allows for prenatal diagnosis and carrier screening. The emergence of Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) represents a transformative advancement in this field, providing the sensitivity and precision required to identify and quantify these critical but elusive biomarkers [15]. This whitepaper details the clinical impact of rare mutations and the instrumental role of ddPCR in their detection within a research context focused on improving patient outcomes.

Digital PCR: A Paradigm Shift in Detection Technology

Digital PCR (dPCR) is a third-generation PCR technology that enables the absolute quantification of nucleic acid targets without the need for a standard curve. Its principle relies on partitioning a PCR reaction mixture into thousands to millions of nanoliter-scale reactions, so that each partition contains zero, one, or a few target molecules [3]. Following end-point PCR amplification, the fraction of positive partitions is counted, and the target concentration is calculated using Poisson statistics. This fundamental approach provides several powerful advantages over quantitative PCR (qPCR):

- Absolute Quantification: Eliminates the reliance on external standards, providing direct copy number concentration [3] [15].

- High Sensitivity and Precision: Capable of detecting single molecules, making it ideal for rare mutation detection [3].

- Superior Tolerance to Inhibitors: The partitioning of samples dilutes PCR inhibitors present in the reaction mix, enhancing robustness [3].

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) is a widely adopted implementation of this technology that uses a water-in-oil emulsion to generate partitions. Recent innovations have focused on miniaturizing and automating ddPCR systems, making them suitable for rapid, on-site diagnostics without compromising the performance of bulky, conventional platforms [15].

Experimental ddPCR Protocol for Rare Mutation Detection

The following protocol, adapted from a study on detecting IDH1 mutations in gliomas, outlines a standard ddPCR workflow [15]:

1. Reaction Mixture Preparation:

- Combine

10 μLof 2x ddPCR Supermix for Probes. - Add

1 μLof ddPCR Mutation Detection Assay (20X) containing target-specific and wild-type-specific primers and probes. - Include

1 μLof restriction enzyme (e.g., HaeIII,10 U/μL) to digest genomic DNA and reduce viscosity for improved partitioning. - Add

50 ng/μLof template DNA (e.g., from patient-derived tissue). - Adjust the final volume to

20 μLwith nuclease-free water.

2. Droplet Generation:

- Transfer the

20 μLreaction mixture into an individual well of a droplet generation cartridge. - Add

70 μLof Droplet Generation Oil to the adjacent oil well. - Place the cartridge in a droplet generator. The device uses a flow-focusing method to create thousands of monodisperse, nanoliter-sized water-in-oil droplets, effectively partitioning the sample.

3. PCR Amplification:

- Transfer

40 μLof the generated droplets to a 96-well PCR plate. - Seal the plate with pierceable foil.

- Perform PCR amplification on a thermal cycler using optimized cycling conditions. A typical protocol includes:

- Enzyme activation at

95°Cfor10 minutes. 40 cyclesof:- Denaturation:

94°Cfor30 seconds. - Annealing/Extension:

55–60°Cfor60 seconds.

- Denaturation:

- Enzyme deactivation:

98°Cfor10 minutes. - Hold at

4°C.

- Enzyme activation at

4. Droplet Reading and Analysis:

- Load the PCR-amplified plate into a droplet reader.

- The reader aspirates droplets one-by-one, passing them through a fluorescence detector.

- Fluorescence signals (e.g., FAM for mutant targets, HEX/VIC for wild-type targets) are measured for each droplet.

- Data analysis software (e.g., Quantasoft) classifies droplets as positive or negative for each fluorescence channel and calculates the absolute concentration of the target (copies/μL) based on the fraction of positive droplets and Poisson statistics [15] [16].

Clinical Applications and Quantitative Impact

The application of ddPCR for rare mutation detection has yielded substantial clinical benefits across multiple domains, particularly in oncology. The following table summarizes key clinical applications and their documented impact.

Table 1: Clinical Applications and Performance of ddPCR in Rare Mutation Detection

| Clinical Application | Target | Clinical Significance | Reported Performance | Source/Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glioma Diagnosis & Prognosis | IDH1 R132H mutation | Differentiates IDH-mutant glioma (median survival: ~11.4 yrs) from IDH-wildtype glioblastoma (median survival: ~14.6 mos) [15]. | 92% Sensitivity, 100% Specificity [15] | Portable ddPCR System [15] |

| Liquid Biopsy & MRD | RAS oncogene mutations | Enables non-invasive detection of tumor DNA in blood; monitoring of treatment response and recurrence in colorectal cancer [3]. | Detected 2 mutant sequences in 160,000 wild-type sequences [3] | Early dPCR (Limiting Dilution) [3] |

| Infectious Disease | HIV provirus | Quantifies viral load by detecting single copies of HIV provirus in infected cells, correlating with disease stage [3]. | Detected 1 infected cell per 5000-80,000 PBMCs in asymptomatic patients [3] | Early dPCR (Limiting Dilution) [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful ddPCR assays depend on a suite of specialized reagents and instruments. The table below details key components used in the featured IDH mutation detection study and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ddPCR Mutation Detection

| Item | Function / Role in the Assay | Example from Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| ddPCR Supermix | Provides optimized buffer, dNTPs, DNA polymerase, and other reagents essential for PCR amplification in a droplet format. | Bio-Rad ddPCR Supermix for Probes [15] [16] |

| Mutation Detection Assay | Target-specific primers and fluorescently-labeled probes (e.g., TaqMan) that distinguish between wild-type and mutant sequences. | ddPCR Mutation Detection Assay for IDH1-R132H [15] |

| Restriction Enzyme | Digests long genomic DNA fragments to prevent entanglement and ensure efficient and random partitioning into droplets. | HaeIII restriction enzyme [15] |

| Droplet Generation Oil | Creates a stable water-in-oil emulsion, forming the individual partitions in which PCR reactions occur. | Bio-Rad Droplet Generation Oil [15] [16] |

| Template DNA | The sample containing the nucleic acid target of interest; quality and quantity are critical for accurate quantification. | 50 ng/μL of patient-derived glioma tissue DNA [15] |

Visualizing the ddPCR Workflow and Data Analysis

The following diagrams, created using the specified color palette and contrast-compliant design rules, illustrate the core workflow and data analysis logic of ddPCR.

Diagram 1: Core ddPCR Workflow. The process involves sample preparation, partitioning into droplets, PCR amplification, fluorescence reading, and data analysis.

Diagram 2: ddPCR Data Analysis Logic. Fluorescence data is used to classify droplets, and the count of positive and negative droplets is used for absolute quantification via Poisson statistics.

The detection of rare mutations is no longer a research curiosity but a clinical necessity for advancing personalized medicine. ddPCR technology, with its unparalleled sensitivity, precision, and robustness, provides a critical tool for researchers and clinicians to uncover these mutations in various contexts, from guiding cancer therapy to diagnosing genetic disorders. As the technology continues to evolve toward greater automation, miniaturization, and integration, its role in routine clinical diagnostics and drug development is poised to expand significantly, offering new hope for early intervention and improved patient outcomes.

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) represents a transformative advancement in molecular diagnostics, offering unparalleled precision for detecting rare genetic mutations. This technical guide elucidates the core principles underpinning ddPCR's superior sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility, framed within the context of oncology research and rare allele detection. By providing absolute quantification without standard curves, demonstrating resilience to PCR inhibitors, and enabling single-molecule detection, ddPCR establishes a new paradigm for biomarker discovery, liquid biopsy applications, and clinical diagnostics. We present experimental validation data, detailed methodologies, and analytical frameworks that confirm ddPCR's robust performance in detecting rare mutations, quantifying gene copy number variations, and identifying low-abundance pathogens, solidifying its critical role in advancing personalized medicine.

Digital PCR (dPCR), the third generation of PCR technology after conventional PCR and real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR), operates on a fundamentally different principle than its predecessors [3] [1]. By partitioning a PCR reaction mixture into thousands to millions of nanoliter-sized reactions, dPCR enables the absolute quantification of nucleic acid targets through Poisson statistical analysis of the binary positive/negative endpoint signals [3] [1]. This partitioning strategy allows dPCR to achieve single-molecule sensitivity, making it particularly powerful for applications requiring the detection of rare genetic events. Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) specifically utilizes a water-in-oil emulsion system to generate these partitions, typically creating thousands of droplets that function as individual microreactors [17] [3]. The technology's development, pioneered by Bert Vogelstein and colleagues who coined the term "digital PCR" in 1999, has evolved through significant microfabrication and microfluidics advances to become a robust, commercially available platform that provides calibration-free quantification with exceptional accuracy and reproducibility [3] [1].

The core workflow encompasses four critical steps: (1) partitioning the sample-PCR mixture into numerous discrete compartments; (2) endpoint PCR amplification within each partition; (3) fluorescence detection to classify partitions as positive or negative; and (4) absolute quantification of target concentration based on the fraction of positive partitions using Poisson statistics [3] [1]. This process eliminates the reliance on external standard curves and cycle threshold (Ct) values inherent to qPCR, thereby reducing quantification variability and enhancing measurement precision [17] [10]. For rare mutation detection—where identifying a few mutant alleles amidst a vast background of wild-type sequences is critical—ddPCR's partitioning approach provides a decisive advantage by effectively concentrating rare targets into detectable positive signals through massive sample fractionation [3].

Unmatched Sensitivity

The exceptional sensitivity of ddPCR stems directly from its ability to partition samples into thousands of individual reactions, effectively concentrating rare targets and enabling single-molecule detection. This section details the quantitative evidence and methodological approaches that establish ddPCR's superior sensitivity for rare mutation detection.

Single-Molecule Detection and Limits of Detection

ddPCR achieves remarkable sensitivity through statistical partitioning, allowing detection of rare mutations at frequencies as low as 0.001%–0.0001% in optimal conditions [3]. In practical applications, this sensitivity translates to reliable detection of minimal residual disease, circulating tumor DNA, and occult infections that remain undetectable by conventional methods. A comparative study of ddPCR platforms demonstrated a Limit of Detection (LOD) of approximately 0.17 copies/μL input for the QX200 system, equivalent to 3.31 copies per 20μL reaction [18]. The same study established a Limit of Quantification (LOQ) of 4.26 copies/μL input (85.2 copies/reaction), confirming ddPCR's ability to both detect and precisely quantify minimal target concentrations [18].

Table 1: Sensitivity Performance Metrics Across ddPCR Applications

| Application Domain | Detection Limit | Quantification Limit | Platform | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Oligonucleotides | 0.17 copies/μL | 4.26 copies/μL | QX200 ddPCR | [18] |

| Pathogen Detection (Plasma) | 0.5 copies/μL (most bacteria) | N/R | Auto-Pure System | [19] |

| Fungal Detection (Plasma) | 1.0 copies/μL (Candida) | N/R | Auto-Pure System | [19] |

Experimental Protocol for Sensitivity Validation

The validation of ddPCR sensitivity follows a standardized approach utilizing serial dilutions to establish detection boundaries. The protocol involves:

- Sample Preparation: Create a dilution series of the target nucleic acid, spanning from clinically relevant concentrations to near-zero concentrations [18].

- Partitioning: Utilize microfluidic chips to generate approximately 20,000 droplets per reaction, ensuring optimal Poisson distribution [17] [18].

- Thermal Cycling: Perform endpoint PCR with target-specific primers and probes under optimized cycling conditions (e.g., 50°C for 10 min, 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10s and 58°C for 45s) [17].

- Droplet Reading: Analyze droplets using a fluorescent detector to distinguish positive from negative partitions [17] [18].

- Statistical Analysis: Apply Poisson statistics to calculate target concentration, determining LOD and LOQ through regression analysis of the dilution series [18].

This methodological framework ensures that sensitivity claims are empirically validated and reproducible across laboratories, establishing ddPCR as the preferred technology for detecting rare mutations in complex biological samples.

Exceptional Specificity

ddPCR achieves exceptional specificity through a combination of optimized probe chemistry, thermal cycling conditions, and dual-signature verification within individual partitions. This multi-layered approach ensures accurate discrimination between closely related sequences, which is paramount for reliable rare mutation detection.

Probe-Based Discrimination and Experimental Validation

The specificity of ddPCR is fundamentally enhanced through TaqMan probe chemistry, which requires both primer annealing and probe hybridization for fluorescent signal generation [17]. This dual requirement significantly increases specificity compared to intercalating dye-based methods. In a bladder cancer study targeting FRS2 copy number variation, researchers designed specific primers (FRS2 forward: 5'-GCCTACAACTCCCCTTCCAC-3', reverse: 5'-TCATCTCGTGGCAGTGCTTT-3') and a FAM-labeled probe (5'-FAM-TTGACATAGCAGCAGTTCTCTCGA-BHQ-3') that clearly distinguished target sequences from homologous regions [17]. The assay demonstrated no interference between primers and probes when performing duplex detection of FRS2 and the reference gene RPP30 within the same reaction, confirming target specificity [17].

Validation against fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) demonstrated 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity for detecting FRS2 amplification, with a kappa value of 1 indicating perfect agreement between the methods [17]. This level of specificity is critical for clinical applications where false positives could lead to inappropriate treatment decisions. The binary nature of ddPCR readout—where partitions are unequivocally classified as positive or negative based on fluorescence amplitude—further enhances specificity by eliminating the subjective interpretation often associated with analog signals [17] [3].

Specificity Optimization Techniques

Several technical approaches can further enhance ddPCR specificity:

- Thermal Gradient Optimization: Empirical determination of optimal annealing temperatures for each primer-probe set significantly reduces non-specific amplification [17].

- Restriction Enzyme Digestion: Pre-digestion with enzymes such as HaeIII or EcoRI improves precision, especially for targets with high copy numbers or complex structures [18].

- Multi-Color Probe Design: Utilizing different fluorescent dyes (FAM, HEX/VIC, Cy5) for multiple targets enables specific detection within the same reaction while monitoring potential cross-reactivity [17] [18].

Table 2: Specificity Validation in Clinical Applications

| Application | Specificity Metric | Validation Method | Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRS2 CNV in Bladder Cancer | Agreement with FISH | Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization | 100% Specificity | [17] |

| Pathogen Detection in Febrile Patients | Clinical Correlation | Conventional Microbiological Testing | 26.3% Specificity (vs. CMT) | [19] |

| Platform Comparison | Restriction Enzyme Impact | EcoRI vs. HaeIII Digestion | HaeIII Improved Specificity | [18] |

Superior Reproducibility

The reproducibility of ddPCR represents one of its most compelling advantages for research and clinical applications. By eliminating variations associated with standard curves and amplification efficiency, ddPCR delivers consistent, precise measurements across different instruments, laboratories, and timepoints.

Quantitative Precision Metrics

ddPCR demonstrates exceptional precision across technical and biological replicates, as evidenced by low coefficients of variation (CV%) in multiple studies. In the FRS2 copy number assay, researchers reported intra-assay CV% of 2.58% and 3.75%, and inter-assay CV% of 2.68% and 3.79% across 20 ng and 2 ng input DNA levels, respectively [17]. These remarkably low variation coefficients confirm the technology's robustness for serial monitoring applications, such as tracking treatment response through liquid biopsies.

A comprehensive platform comparison study further validated ddPCR's reproducibility, demonstrating that both droplet-based (QX200) and nanoplate-based (QIAcuity) systems achieved high precision across most analyses, with CVs ranging between 6% to 13% for ddPCR across various concentration levels [18]. The study noted that precision could be further optimized through restriction enzyme selection, with HaeIII demonstrating superior performance compared to EcoRI, particularly for the QX200 system where CVs improved to below 5% for all cell numbers tested [18].

Factors Enhancing Reproducibility

Several technological features contribute to ddPCR's superior reproducibility:

- Absolute Quantification Without Standard Curves: By counting discrete molecules rather than comparing to standard curves, ddPCR eliminates a major source of inter-laboratory variability [3] [1].

- Endpoint Detection: Measuring fluorescence after PCR completion avoids variations associated with amplification efficiency differences that affect Ct values in qPCR [10] [3].

- Partitioning Normalization: The massive sample partitioning minimizes the impact of PCR inhibitors, generating more consistent results across challenging sample matrices [10] [19].

- Poisson Statistical Foundation: The mathematical framework accounts for random distribution effects, providing statistically robust concentration calculations [3] [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing ddPCR for rare mutation detection requires specific reagents and optimized experimental components. The following table details essential materials and their functions based on validated protocols from recent research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ddPCR Rare Mutation Detection

| Reagent/Component | Function | Example Specification | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target-Specific Primers | Amplification of target sequence | FRS2: 5'-GCCTACAACTCCCCTTCCAC-3' and 5'-TCATCTCGTGGCAGTGCTTT-3' [17] | HPLC purification recommended for long primers |

| Fluorescent Probes (TaqMan) | Sequence-specific detection | FRS2: 5'-FAM-TTGACATAGCAGCAGTTCTCTCGA-BHQ-3' [17] | FAM/HEX/Cy5 dyes for multiplexing; BHQ quenchers |

| Reference Gene Assay | Normalization control | RPP30: 5'-ROX-CTGACCTGAAGGCTCT-BHQ1-3' [17] | Different fluorescent channel than target |

| Restriction Enzymes | Enhance DNA accessibility | HaeIII or EcoRI [18] | HaeIII showed superior precision in comparative studies |

| Digital PCR Supermix | Partition stability & amplification | 2× Aplµs Digital PCR Mix [17] | Contains polymerase, dNTPs, optimized buffers |

| Microfluidic Chips | Partition generation | C4 chips (DropXpert S6 system) [17] | Generates ~20,000 droplets per reaction |

| Negative Controls | Contamination monitoring | DNase-free water [19] | Essential for establishing background signals |

| Synthetic DNA Standards | Assay validation | Custom oligonucleotides with target sequence [18] | Verify LOD, LOQ, and linearity |

Droplet Digital PCR establishes a new standard for sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility in molecular detection, particularly for challenging applications like rare mutation detection in cancer research. The technology's unparalleled performance stems from its fundamental partitioning approach, which enables absolute quantification of nucleic acids without standard curves, reduces susceptibility to inhibitors, and provides statistically robust counting of individual molecules. As evidenced by the rigorous validation studies cited herein, ddPCR consistently demonstrates the ability to detect rare mutations with precision unattainable by conventional PCR methods. The detailed experimental protocols and reagent specifications provided in this technical guide offer researchers a framework for implementing ddPCR in their own laboratories, potentially accelerating discoveries in biomarker identification, liquid biopsy development, and personalized therapeutic monitoring. With ongoing advancements in microfluidics, multiplexing capabilities, and automated workflows, ddPCR is poised to remain at the forefront of molecular diagnostics, providing the precision necessary to decipher biological complexity and guide clinical decision-making.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing ddPCR in Liquid Biopsies and Disease Monitoring

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) represents a third-generation polymerase chain reaction technology that enables absolute quantification of nucleic acids without the need for a standard curve [3] [20]. This revolutionary approach is based on the concept of sample partitioning and endpoint PCR analysis, fundamentally transforming capabilities for rare mutation detection in modern research laboratories [20]. The core technological advantage of ddPCR lies in its physical segregation of the sample into thousands of tiny, uniform water-in-oil emulsion droplets—typically 20,000 or more per reaction—with each droplet acting as an independent micro-reactor [20]. This partitioning process converts a continuous measurement of concentration into a digital readout, conferring the technology's characteristic robustness and sensitivity essential for detecting rare genetic mutations that constitute less than 0.1% of the total nucleic acid population [3] [20].

The complete ddPCR workflow encompasses three critical phases: sample preparation, partitioning, and end-point analysis [3]. Each phase must be meticulously optimized to ensure the high sensitivity, accuracy, and precision required for rare mutation detection in research and drug development applications [21]. The fundamental mechanism relies on Poisson statistics, where the random distribution of template molecules into partitions ensures that most droplets contain either zero or one copy of the target molecule, allowing for absolute quantification through binary endpoint detection [3] [20]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of each workflow component, with particular emphasis on methodological considerations for rare mutation detection research.

Sample Preparation: Optimizing Input Material

Conventional Nucleic Acid Extraction

Sample preparation constitutes the most variable phase of the ddPCR workflow and profoundly impacts assay performance, especially for rare target detection [21]. Conventional approaches utilize commercially available genomic DNA extraction kits that include purification steps through silica columns, magnetic beads, or ethanol precipitation [21]. These methods work effectively for cultured cells or samples with abundant cellular material (typically greater than 100,000 cells) but present significant challenges for clinical samples with limited cell numbers [21]. When working with limited samples containing fewer than 1,000 cells, target loss during extraction becomes a substantial concern that can compromise rare mutation detection sensitivity [21].

For circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis in liquid biopsy applications, specific considerations for cell-free DNA (cfDNA) extraction must be implemented. The recommended serum input volume for optimal sensitivity in viral load detection has been demonstrated at 200μL, which is lower than most conventional real-time PCR assays require [22]. This reduced input requirement is particularly advantageous when analyzing precious clinical samples or when additional blood collection from patients is challenging [22]. Extraction methods that maximize recovery of short-fragment cfDNA are essential for oncology applications where ctDNA may represent less than 0.01% of total cfDNA [20].

Innovative Approaches for Limited Samples

Recent methodological advances address the challenges of limited sample material. A novel crude lysate approach eliminates the DNA extraction and purification steps entirely, thereby preventing target loss during extraction [21]. This method is particularly valuable for quantifying rare targets from minimal cell samples, such as T stem cell memory cells that constitute only 2-4% of the total T cell population or antigen-specific T cells that may be present at frequencies of 1 per 100 to 100,000 cells [21].

The crude lysate protocol incorporates a critical viscosity breakdown (VB) step prior to droplet generation to address the challenge of intact oligonucleotides in cellular lysates increasing viscosity and impairing droplet formation [21]. Research demonstrates that samples processed without the VB protocol exhibited unexpected droplet spreading on the 2D plot, making threshold determination challenging, and showed significant differences in generated droplet numbers compared to VB-processed samples [21]. Importantly, the VB step eliminated systematic overestimation of target copies observed in non-VB protocols (0.046 TRECs/cell without VB versus 0.029 with standard ddPCR), establishing its essential role in ensuring measurement accuracy [21].

The performance of crude lysate methods depends heavily on lysis buffer composition. Comparative studies identified Buffer 2 (from SuperScript IV CellsDirect cDNA Synthesis Kit) as superior to Buffer 1 (from Ambion Cell-to-Ct kit), with Buffer 2 demonstrating excellent linearity (r² > 0.99) across a range of 200-16,000 cells and accurate quantification without systematic overestimation [21]. This optimized crude lysate protocol achieved a limit of detection of 0.0001 TRECs/cell, enabling reliable rare target detection from as few as 200 cells [21].

Sample Quality Assessment

Robust sample quality control is prerequisite for reliable ddPCR analysis, particularly in rare mutation detection where suboptimal sample quality can profoundly impact results. A ddPCR-based cell counting assay targeting the single-copy RPP30 gene has been developed to accurately quantify cell numbers, overcoming the high variability associated with traditional cell counting methods that depend on site, methodology, and operator expertise [23]. This approach demonstrates exceptional reproducibility across laboratories, with applications extending to normalization of tissue homogenates from various sources [23].

For monitoring DNA sample integrity during storage, ddPCR provides significant advantages over traditional methods like gel electrophoresis, UV absorbance, and qPCR [23]. The technology's absolute quantification capability without standard curves enables precise assessment of DNA degradation and quantification of losses due to tube binding, facilitating improved sample storage protocols [23].

Partitioning: Microfluidic Droplet Generation

Principles of Partitioning

Partitioning constitutes the defining step of the ddPCR workflow, where the PCR mixture is physically segregated into thousands to millions of discrete reaction compartments [3]. This partitioning process follows Poisson distribution statistics, where nucleic acid targets are randomly distributed among the partitions such that each compartment contains either 0, 1, or a few target molecules [3]. The statistical foundation of this approach was established in early work combining limiting dilution PCR with Poisson statistics to isolate, detect, and quantify single nucleic acid molecules [3].

Two major partitioning methodologies have emerged: water-in-oil droplet emulsification (ddPCR) and microchamber-based systems [3]. Droplet-based systems offer greater scalability and cost-effectiveness, while microchamber platforms provide higher reproducibility and ease of automation but are limited by fixed partition numbers and typically higher costs [3]. The number of partitions directly impacts quantification accuracy, with higher partition counts enabling more precise rare allele detection by ensuring adequate representation of low-frequency targets within the statistical sample [20].

Microfluidic Technology

Microfluidic technology is central to creating the uniform, stable droplets that define the ddPCR process [3] [20]. Monodisperse droplets are typically generated at high speed (1-100 kHz) using microfluidic chips that leverage passive forces or actively break the aqueous/oil interface [3]. Modern commercial systems like the QX ONE Droplet Digital PCR System have automated this process, integrating droplet generation, PCR amplification, and droplet reading into a single platform capable of analyzing 480 samples daily [23] [24].

Droplet stability represents a critical technical consideration throughout the workflow. Water-in-oil droplets are prone to coalescence, particularly during the rigorous temperature variations of PCR thermocycling [3]. Appropriate surfactant formulations are essential for maintaining droplet integrity, with specialized Droplet Generation Oil formulations containing proprietary surfactants that prevent droplet merging while ensuring compatibility with biochemical reactions [22]. Empirical validation of droplet volume is recommended, as studies have demonstrated actual droplet volumes (0.70nL) may differ from manufacturer specifications (0.85nL), necessitating adjustment of concentration calculations to maintain accurate quantification [21].

Digital PCR Partitioning Workflow

End-point Analysis: Detection and Quantification

Fluorescence Detection Technologies

Following endpoint PCR amplification, droplets undergo individual fluorescence analysis to determine target presence or absence [3] [20]. Two primary readout methodologies exist: in-line detection and planar imaging [3]. In-line detection, commonly employed in ddPCR systems, involves flowing droplets sequentially through a microfluidic channel or capillary where fluorescence is measured using a light source coupled to detectors [3]. This approach enables analysis of large droplet numbers but requires precise flow control [3]. Planar imaging captures static snapshots of microchamber arrays or deposited microdroplets using fluorescence microscopy or scanners [3]. Advanced 3D imaging and analysis techniques have been developed to assay larger droplet numbers in reduced timeframes [3] [25].

Modern ddPCR platforms feature multi-channel fluorescence detection capabilities essential for multiplex applications. While earlier systems like the QX200 were limited to two-color fluorescence, restricting multiplex detection complexity, newer platforms including the QX ONE incorporate four independent fluorescence channels, enabling simultaneous detection of multiple targets in a single reaction [24]. This advancement facilitates development of sophisticated multiplex assays, such as the automated high-throughput quadruplex RT-ddPCR assay (AHQR-ddPCR) that simultaneously detects influenza A, influenza B, respiratory syncytial virus, and SARS-CoV-2 [24].

Data Analysis and Poisson Statistics

The fundamental principle of ddPCR quantification relies on Poisson statistics applied to the binary readout of positive versus negative partitions [3] [20]. The fraction of positive partitions enables computation of the target concentration based on Poisson distribution parameters, providing absolute quantification without external calibration [3]. This statistical approach accounts for the random distribution of targets among partitions, including the probability that some partitions received multiple copies, thereby enabling accurate back-calculation of the true starting concentration [20].

The Poisson model is expressed mathematically as:

[C = -\frac{\ln(1 - p)}{V}]

Where (C) represents the target concentration (copies/μL), (p) is the proportion of positive partitions, and (V) is the partition volume [20]. This calculation is automatically performed by instrument software such as Bio-Rad's QuantaSoft, which applies automatic thresholding based on fluorescence amplitude to classify partitions as positive or negative [22]. For rare mutation detection, the high degree of partitioning (20,000+ droplets) ensures that even minimal target concentrations are reliably detected and quantified, enabling discrimination of mutant allele frequencies below 0.1% [20].

Advanced Analysis and Artificial Intelligence

Emerging analytical approaches incorporate artificial intelligence to enhance ddPCR data interpretation. AI-driven fluorescence image analysis represents a significant advancement, with evolution from classical classifiers to modern deep learning and foundation models (e.g., SAM, ViT, GPT-4o) improving analytical precision [25]. These computational methods address challenges in partition diversity, signal interpretation, and workflow integration, particularly for point-of-care testing applications [25]. Structured frameworks redefining dNAAT into five stages (Sample Preparation, Partition, Amplification, Detection, and Analysis) highlight opportunities for AI-enhanced precision, scalability, and automation at each workflow step [25].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The exceptional analytical performance of ddPCR is demonstrated through rigorous validation studies across diverse applications. The tables below summarize key performance metrics established through recent research.

Table 1: Analytical Sensitivity of ddPCR Assays Across Applications

| Application | Target | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) | Sample Input | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis B Viral Load | HBV X gene | 1.6 IU/mL | 9.4 IU/mL | 200 μL serum | [22] |

| Respiratory Virus Detection | Influenza A | 0.65 copies/μL | N/R | 5 μL RNA | [24] |

| Respiratory Virus Detection | Influenza B | 0.78 copies/μL | N/R | 5 μL RNA | [24] |

| Rare DNA Circles | TRECs | 0.0001 copies/cell | N/R | 200 cells | [21] |

Table 2: Precision and Reproducibility Metrics

| Application | Intra-run Variability (CV) | Inter-run Variability (CV) | Linearity (R²) | Specificity | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis B Viral Load | 0.69% | 4.54% | 0.988 | 96.2% | [22] |

| Copy Number Variation | N/R | N/R | N/R | 95% concordance with PFGE | [26] |

| Rare Target Detection | High reproducibility across laboratories | N/R | >0.99 (Buffer 2) | No false positives with VB protocol | [21] [23] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for ddPCR Workflow

| Reagent/Kits | Function | Application Notes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| QX ONE ddPCR System | Integrated partitioning, thermocycling, reading | Automated high-throughput (480 samples/day); 4-color detection | [23] [24] |

| One-Step RT–ddPCR Advanced Kit for Probes | Reverse transcription and PCR amplification | Enables direct RNA detection; includes reverse transcriptase and supermix | [24] |

| Droplet Generation Oil | Forms stable water-in-oil emulsion | Critical for droplet integrity; contains proprietary surfactants | [22] |

| Cell Lysis Buffer (Buffer 2) | Cellular lysis without DNA purification | Superior performance for crude lysate preparations from limited samples | [21] |

| QIAamp MinElute Virus Spin Kit | Nucleic acid extraction | Optimized for viral DNA/RNA from serum/plasma; elution volume 16μL | [22] |

| RPP30 Assay | Reference gene for cell counting | Absolute quantification of cell numbers; normalizes sample input | [23] |

The integrated workflow of sample preparation, partitioning, and end-point analysis in ddPCR provides researchers with an exceptionally powerful tool for rare mutation detection. The technology's absolute quantification capability, independence from standard curves, and exceptional sensitivity enable applications previously challenging with conventional PCR methods [20]. Ongoing advancements in sample preparation methodologies, particularly for limited samples, microfluidic partitioning technologies, and AI-enhanced data analysis continue to expand the frontiers of molecular detection [21] [25]. For research and drug development professionals focused on high-stakes applications such as liquid biopsy, viral load monitoring, and genetic variation studies, mastery of the complete ddPCR workflow is essential for generating reliable, reproducible, and clinically actionable data [27] [20]. As the technology continues to evolve with improved automation, multiplexing capabilities, and analytical sophistication, its role in precision medicine and molecular diagnostics is poised for significant expansion [25] [27].

Liquid biopsy represents a transformative approach in oncology, shifting the paradigm from traditional tissue biopsy to minimally invasive detection of tumor-derived components in body fluids. Among these components, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has emerged as a predominant biomarker due to its ability to provide a real-time snapshot of tumor genomics [28] [29]. ctDNA consists of short fragments of DNA released into the bloodstream primarily through apoptosis and necrosis of tumor cells, carrying tumor-specific genetic and epigenetic alterations [30] [31]. Unlike conventional tissue biopsy, which captures a single spatial and temporal point, ctDNA analysis reflects tumor heterogeneity and evolving genomic landscapes, enabling dynamic monitoring throughout the disease course [29] [31].

The clinical significance of ctDNA stems from its correlation with tumor burden and cellular turnover [31]. In patients with advanced cancer, ctDNA can constitute upwards of 90% of total cell-free DNA (cfDNA), though this percentage drops significantly in early-stage disease, often falling below 1% [31]. The half-life of ctDNA is remarkably short, estimated between 15 minutes to several hours, allowing for near real-time assessment of treatment response and disease progression [30] [31]. These characteristics make ctDNA an exceptionally dynamic biomarker for precision oncology applications, including treatment selection, response monitoring, minimal residual disease (MRD) detection, and identification of resistance mechanisms [32] [31].

Biological Foundations and Technical Challenges

Origin and Characteristics of ctDNA

ctDNA originates from tumor cells through various mechanisms, with apoptosis and necrosis being the primary sources [30]. Apoptosis produces uniformly short DNA fragments (approximately 160-180 base pairs), while necrosis generates more variable fragment sizes [29]. Additional release mechanisms include phagocytosis, active secretion, and neutrophil extracellular traps [30]. A key distinguishing feature of tumor-derived DNA is its fragmentation pattern; ctDNA fragments are typically shorter than non-tumor cfDNA, with enrichment of fragments between 90-150 base pairs [29] [30]. This fragmentation signature, along with end-motif patterns, provides additional discriminative power for detecting tumor-derived DNA amidst the background of normal cfDNA [28] [31].

The concentration of ctDNA in circulation varies significantly based on cancer type, stage, and tumor location [30]. While ctDNA levels generally correlate with tumor burden, this relationship is not absolute, as some tumors exhibit higher shedding rates than others independent of size [30] [31]. Additionally, ctDNA is not uniformly distributed throughout the bloodstream, presenting analytical challenges for reliable detection, particularly in early-stage disease where tumor DNA represents only a minute fraction of total cfDNA [33] [31].

Technical Hurdles in ctDNA Analysis

The detection and analysis of ctDNA face several significant technical challenges that must be addressed for successful implementation:

Low Abundance: In early-stage cancers, ctDNA can represent as little as 0.01% of total cfDNA, requiring exceptionally sensitive detection methods [34]. This low variant allele frequency (VAF) demands techniques capable of distinguishing true mutations from background noise and technical artifacts [33] [31].

Pre-analytical Variables: Sample collection, processing, and storage conditions significantly impact ctDNA integrity and yield [28]. Variables including blood collection tube type, time-to-processing, centrifugation protocols, and storage temperature can introduce biases that affect downstream analysis [35]. Standardization of these pre-analytical steps is crucial for reproducible results [28].

Tumor Heterogeneity: The genetic diversity within and between tumor sites presents challenges for designing assays that comprehensively capture the molecular landscape [34]. While ctDNA theoretically represents the entire tumor ecosystem, in practice, low-frequency subclones may evade detection if assay sensitivity is insufficient [31].

Clonal Hematopoiesis: Age-related mutations in blood cells can contribute cfDNA variants that mimic tumor-derived mutations, potentially leading to false positive results [33]. Distinguishing somatic tumor mutations from clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) requires careful bioinformatic filtering or matched analysis of white blood cells [33].

Table 1: Key Technical Challenges in ctDNA Analysis and Potential Mitigation Strategies

| Challenge | Impact on Analysis | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Low Abundance | Limits detection sensitivity in early-stage cancer | Unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), error-suppressed sequencing, deep sequencing |

| Pre-analytical Variability | Introduces bias and affects reproducibility | Standardized collection protocols, plasma separation within 4h, use of stabilizing tubes |

| Tumor Heterogeneity | Incomplete representation of molecular landscape | Large gene panels, whole-genome approaches, multi-analyte integration |

| Clonal Hematopoiesis | False positive variant calls | Matched white blood cell sequencing, bioinformatic filtering, epigenetic profiling |

Detection Methodologies and Platforms

PCR-Based Approaches

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods form the foundation of ctDNA detection, offering rapid turnaround times and high sensitivity for known mutations [28] [31]. Digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) and BEAMing (beads, emulsion, amplification, and magnetics) technologies enable absolute quantification of mutant alleles by partitioning reactions into thousands of individual droplets, allowing for detection of rare variants with variant allele frequencies as low as 0.001% in some optimized assays [28]. These methods are particularly valuable for monitoring specific driver mutations in genes such as BRAF (melanoma), KRAS (lung and colorectal cancer), ESR1 (breast cancer), and AR (prostate cancer) [31]. The primary limitation of PCR-based approaches is their restriction to a small number of predefined mutations, making them less suitable for discovery applications or heterogeneous tumors with diverse mutation profiles [31].

Next-Generation Sequencing Strategies

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has dramatically expanded the scope of ctDNA analysis, enabling comprehensive profiling of multiple genomic alterations simultaneously [30] [31]. NGS approaches for ctDNA can be broadly categorized into targeted and untargeted methods: