dPCR vs qPCR for Mutant Allele Detection: A Strategic Guide for Precision Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of digital PCR (dPCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) for the detection and quantification of mutant alleles, a critical task in oncology, biomarker validation, and...

dPCR vs qPCR for Mutant Allele Detection: A Strategic Guide for Precision Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of digital PCR (dPCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) for the detection and quantification of mutant alleles, a critical task in oncology, biomarker validation, and drug development. We explore the foundational principles of both technologies, detail methodological approaches for specific applications like rare variant detection and copy number variation analysis, and offer practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. By synthesizing recent comparative data and validation guidelines, this guide empowers researchers and drug development professionals to select the optimal PCR strategy for their specific sensitivity, precision, and throughput requirements in mutant allele analysis.

Core Principles: How dPCR and qPCR Work for Nucleic Acid Quantification

In the fields of molecular biology, clinical diagnostics, and drug development, accurately measuring nucleic acids is fundamental to understanding disease mechanisms, validating therapeutic targets, and developing diagnostic assays. The emergence of targeted nucleases like CRISPR/Cas9 has dramatically accelerated the pace of generating mutant cell lines and animal models, making efficient and accurate genotyping a critical step in the research pipeline [1]. At the core of this quantification challenge lies a fundamental methodological divide: absolute quantification versus relative quantification. These approaches differ not merely in calculation method, but in their underlying principles, technical requirements, and applications.

Absolute quantification determines the exact number of target DNA or RNA molecules in a sample, expressed as copies per unit volume [2] [3]. In contrast, relative quantification expresses the amount of target relative to a reference sample or control gene, typically presented as fold-change differences [2]. This distinction becomes particularly significant in the context of detecting mutant alleles, where precise measurement of allele frequencies can inform disease prognosis and treatment strategies. The choice between digital PCR (dPCR) and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) often hinges on this quantification paradigm, with each technology offering distinct advantages for specific applications in research and drug development.

Core Principles: A Comparative Framework

Absolute Quantification

Absolute quantification provides a direct count of target molecules without comparison to external standards or endogenous controls. In digital PCR, this is achieved through limiting dilution and Poisson statistical analysis. The sample is partitioned into thousands of individual reactions, some of which contain the target molecule (positive) while others do not (negative). The ratio of negative to total reactions enables precise calculation of the absolute target concentration [2] [4].

Key Characteristics:

- Does not require standard curves [4] [3]

- Provides direct copy number concentration [3]

- Independent of amplification efficiency [3]

- Uses endogenous controls only for sample quality assessment, not quantification [2]

Relative Quantification

Relative quantification measures changes in gene expression or nucleic acid concentration in a given sample relative to another reference sample, such as an untreated control. The comparative CT (ΔΔCT) method is commonly used, which compares the cycle threshold (CT) value of the target gene to a reference gene (e.g., a housekeeping gene) [2].

Key Characteristics:

- Requires stable reference genes for normalization [2] [3]

- Results expressed as n-fold difference relative to a calibrator [2]

- Dependent on amplification efficiency [2]

- Standard curves can be used, but units drop out in final calculation [2]

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Absolute and Relative Quantification

| Parameter | Absolute Quantification | Relative Quantification |

|---|---|---|

| Output | Exact copy number/μL | Fold-change relative to control |

| Standard Curve | Not required | Optional for calibration |

| Reference Genes | Not needed for quantification | Essential for normalization |

| Efficiency Compensation | Not required | Critical for ΔΔCT method |

| Primary Applications | Viral load quantification, copy number variation, rare mutation detection | Gene expression studies, response to therapeutic treatment |

Technological Implementation: dPCR vs qPCR

Digital PCR for Absolute Quantification

Digital PCR represents a transformative approach for absolute quantification. The technology partitions a PCR reaction into thousands of nanodroplets or nanowells, effectively creating a digital array of individual PCR reactions. Following amplification, the system counts the positive and negative partitions to provide absolute quantification through Poisson statistics [4] [5].

Recent advancements include real-time dPCR systems that further enhance sensitivity by using amplification curve analysis to eliminate false positive partitions. This approach combines the absolute quantification of dPCR with the analytical benefits of real-time amplification curve analysis, significantly improving the limit of detection for rare allele assays [5].

A key performance advantage of dPCR is its tolerance to inhibitors and capacity to analyze complex mixtures. By partitioning the sample, potential inhibitors are diluted in the positive partitions, minimizing their impact on amplification efficiency [2] [4].

Quantitative PCR for Relative Quantification

Quantitative PCR has long been the gold standard for relative quantification of nucleic acids. The two primary calculation methods are the standard curve method and the comparative CT method. While the standard curve method can approximate absolute quantification if calibrated with standards of known concentration, it remains fundamentally a relative technique when used for gene expression analysis [2].

The comparative CT method offers practical advantages for screening applications, as it does not require standard curves, increases throughput by eliminating standard wells, and allows for multiplexing target and reference genes in the same reaction [2]. However, this method requires rigorous validation to ensure that the amplification efficiencies of target and reference genes are approximately equal [2].

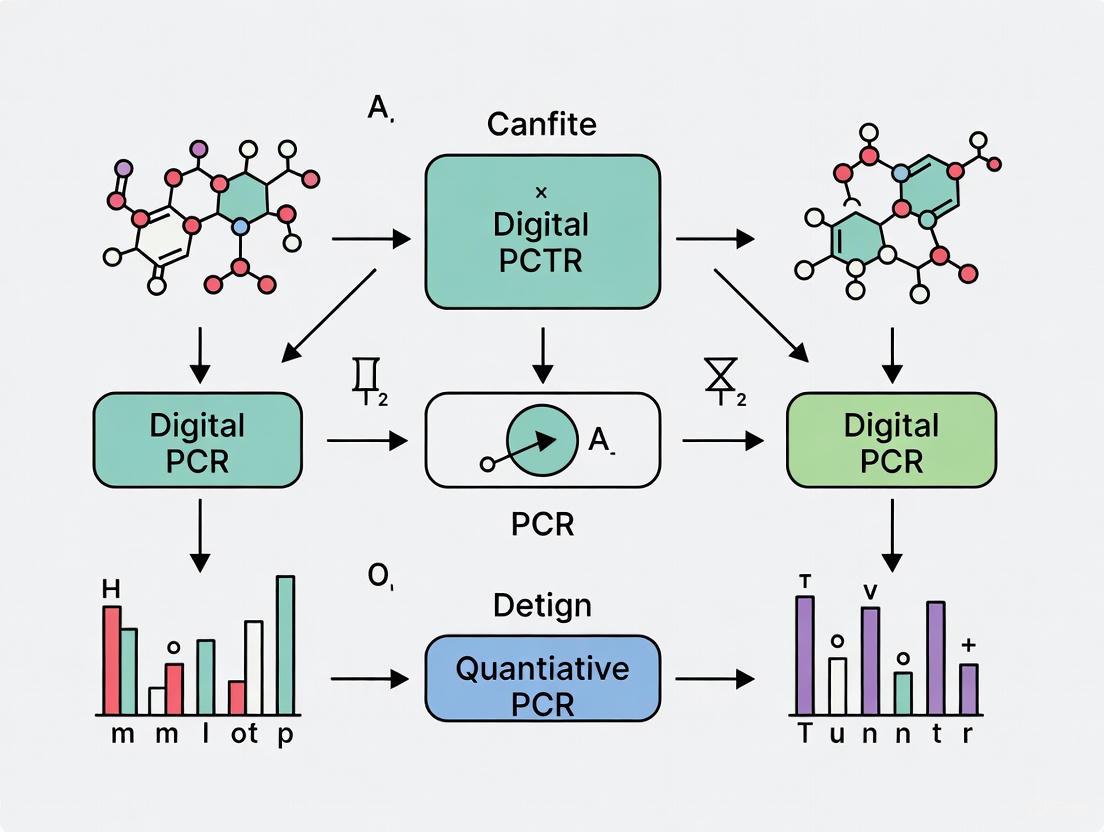

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflows of Digital PCR and Quantitative PCR

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data

Precision and Reproducibility

Multiple studies have directly compared the precision and reproducibility of dPCR and qPCR. In a controlled experiment comparing Crystal Digital PCR (cdPCR) technology to qPCR, researchers analyzed 23 technical replicates from a single PCR master mix spiked with human genomic DNA (175 cp/μl). The results demonstrated that the measurement variability of cdPCR (%CV = 2.3) was more than two-fold lower than that of qPCR (%CV = 5.0) [4].

When cdPCR replicates were pooled and analyzed as single larger samples, the precision advantage increased further, with cdPCR variability (%CV = 1.5) becoming almost three-fold lower (65.9%) than that of qPCR duplicate averages (%CV = 4.4) [4]. This enhanced precision is attributed to dPCR's endpoint determination, direct quantification method, and the high number of partitions generated per sample.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Between dPCR and qPCR

| Performance Metric | Digital PCR | Quantitative PCR | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Variability (%CV) | 2.3% | 5.0% | 23 technical replicates of human genomic DNA [4] |

| Pooled Sample Variability (%CV) | 1.5% | 4.4% | Pooled vs. averaged duplicates [4] |

| Sensitivity for Rare Alleles | Improved detection at lower allele frequencies | Limited by standard curve and efficiency | EGFR mutation detection [5] |

| Effect of Inhibitors | Highly tolerant | Sensitive | Complex biological samples [2] [4] |

| Dynamic Range | 1-100,000 copies/20μL [3] | Broader dynamic range | Manufacturer specifications and experimental data |

Sensitivity in Mutant Allele Detection

The ability to accurately detect and quantify mutant alleles is particularly important in cancer research and personalized medicine. A study comparing real-time dPCR to endpoint dPCR for detecting EGFR mutations (T790M, L858R, and exon 19 deletions) demonstrated that real-time dPCR improved sensitivity by establishing a lower baseline for wild-type samples [5].

For EGFR exon 19 deletion assays, samples with only 2 or more FAM-labeled positive partitions were reliably determined as positive by real-time dPCR, while endpoint dPCR required a minimum of 5 FAM-positive partitions for the same confidence level [5]. This enhanced sensitivity is crucial for liquid biopsy applications, where circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) often represents a small fraction of total cell-free DNA.

In another study focusing on allele-specific quantitative PCR (ASQ), researchers achieved 98-100% concordance in genotype scoring with traditional methods like RFLP or Sanger sequencing while significantly reducing processing time and cost [1]. The open-source ASQ system utilized allele-specific primers, a locus-specific reverse primer, universal fluorescent probes and quenchers, and hot start DNA polymerase to genotype germline mutants through either threshold cycle (Ct) or end-point fluorescence reading [1].

Application in Mutant Allele Research

Genotyping and Mutation Detection

The accelerated pace of generating mutant alleles using customizable endonucleases like TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9 has made traditional genotyping methods a bottleneck in research pipelines [1]. While classic restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) or sequencing is labor-intensive and expensive, allele-specific qPCR methods offer rapid, cost-effective alternatives.

The ASQ (allele-specific qPCR) protocol represents a significant advancement for genotyping applications. This one-step open-source method can genotype germline mutants through either threshold cycle (Ct) or end-point fluorescence reading without post-PCR processing [1]. The system has been successfully validated to genotype alleles in five different genes with high concordance to established methods, making it particularly valuable for high-throughput functional validation of disease-associated alleles [1].

Viral Load Quantification and Co-infections

In respiratory virus diagnostics, accurate quantification is essential for understanding infection dynamics, particularly during co-circulation of multiple pathogens like influenza A, influenza B, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2. A 2025 study comparing dPCR and Real-Time RT-PCR found that dPCR demonstrated superior accuracy, particularly for high viral loads of influenza A, influenza B, and SARS-CoV-2, and for medium loads of RSV [6].

dPCR showed greater consistency and precision than Real-Time RT-PCR, especially in quantifying intermediate viral levels. This precision is critical for monitoring antiviral efficacy, particularly in immunocompromised patients or those with prolonged viral shedding [6]. The absolute quantification provided by dPCR also facilitates the identification of co-infections and assessment of their relative contribution to disease burden, which is not possible with qualitative detection alone [6].

Practical Implementation: Methodologies and Reagents

Experimental Protocols

Allele-Specific Quantitative PCR (ASQ) Protocol [1]:

- Genomic DNA Preparation: Use hot sodium hydroxide (NaOH) extraction method for rapid preparation (25 min incubation in 50 mM NaOH at 95°C with shaking) followed by neutralization with Tris buffer.

- Primer Design: Design allele-specific primers (ASPs) with the discriminatory nucleotide at the 3' end, combined with a locus-specific reverse primer.

- Reaction Setup: Combine ASPs with universal fluorescent probes (FAM or HEX conjugated) and corresponding quenchers (Black Hole Quencher 1).

- Thermal Cycling: Use hot start DNA polymerase with optimized cycling conditions.

- Analysis: Genotype through either threshold cycle (Ct) method in a qPCR machine or end-point fluorescence reading in a plate reader.

Digital PCR Protocol for Rare Allele Detection [5]:

- Sample Preparation: Mix wild-type and mutant genomic DNA in desired ratios based on fluorometric quantification.

- Partitioning: Load samples into dPCR system (chip-based or droplet-based) creating 20,000+ individual partitions.

- Amplification: Perform endpoint PCR with target-specific assays.

- Data Analysis: For real-time dPCR, use amplification curves to eliminate false positive partitions; for endpoint dPCR, use fluorescence thresholds.

- Quantification: Apply Poisson statistics to calculate absolute copy numbers and mutant allele frequencies.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Absolute and Relative Quantification

| Reagent/Instrument | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Allele-Specific Primers | Specifically amplify mutant or wild-type alleles | Design with discriminatory base at 3' end; critical for ASQ [1] |

| Universal Fluorescent Probes | Detection of amplified products | FAM and HEX conjugated; used with shorter quenchers [1] |

| Hot Start DNA Polymerase | Prevents non-specific amplification | Essential for both dPCR and qPCR assays [1] |

| Digital PCR Systems | Partitioning and absolute quantification | Includes chip-based (QIAcuity) and droplet-based (ddPCR) platforms [4] [6] |

| Reference Gene Assays | Normalization for relative quantification | β-actin, GAPDH, rRNA; must demonstrate stable expression [2] [3] |

The choice between absolute and relative quantification methodologies depends fundamentally on the research question and application requirements. Absolute quantification using digital PCR provides superior precision, sensitivity for rare alleles, and tolerance to inhibitors, making it ideal for liquid biopsy applications, viral load quantification, and copy number variation studies [4] [6] [5]. Relative quantification using qPCR remains a robust, cost-effective solution for gene expression studies, particularly when screening large sample sets where fold-change differences provide sufficient biological insight [2] [3].

For mutant allele research, emerging technologies like real-time dPCR and allele-specific qPCR are addressing critical bottlenecks in genotyping workflows. Real-time dPCR significantly improves the limit of detection for rare alleles by eliminating false positives through amplification curve analysis [5], while ASQ provides a rapid, open-source platform for high-throughput genotyping of engineered mutants [1]. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will further empower researchers and drug development professionals in their pursuit of precision medicine and personalized therapeutic strategies.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) is a powerful molecular biology technique that enables the detection and quantification of nucleic acids in real-time during the amplification process. The core principle of qPCR lies in monitoring the fluorescence emitted during each PCR cycle, which is directly proportional to the amount of amplified DNA product. The calibration curve, also known as the standard curve, serves as the fundamental mathematical model that translates the fluorescence detection data into meaningful quantitative results. This curve is generated by amplifying a dilution series of known template concentrations and plotting their quantification cycle (Cq) values against the logarithm of their initial concentrations.

The relationship is described by the linear equation: Cq = slope × log(N₀) + intercept, where the slope is used to calculate the amplification efficiency via the formula E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1 [7] [8]. An ideal PCR reaction with 100% efficiency corresponds to a slope of -3.32, though in practice, reactions with efficiencies between 90-110% (slope of -3.58 to -3.10) are generally considered acceptable [8]. The reliability of this standard curve method has been validated through extensive testing, such as in studies measuring the expression of 6 genes in 42 breast cancer biopsies, demonstrating its utility in routine laboratory practice [7].

The qPCR Workflow: From Fluorescence to Quantification

The transformation of raw fluorescence signals into quantitative data involves a multi-step data processing procedure. The following diagram illustrates this complete workflow:

Data Processing and Noise Filtering

The initial phase of qPCR data analysis focuses on noise filtering to enhance data quality. Raw fluorescence readings often contain non-specific cycle-to-cycle scattering that requires correction. The standard processing approach includes three sequential steps [7]:

- Smoothing: Random cycle-to-cycle noise is reduced using a 3-point moving average (with two-point averages applied at the first and last data points)

- Baseline Subtraction: Background fluorescence is eliminated by subtracting the minimal fluorescence value observed through the entire run

- Amplitude Normalization: Plateau scattering is addressed by normalizing to the maximal fluorescence value in each reaction well over the complete PCR run

This noise filtering process transforms raw fluorescence data into clean amplification curves suitable for reliable crossing point determination [7].

Crossing Point Determination and Standard Curve Generation

The crossing point (CP), also referred to as quantification cycle (Cq), represents the cycle number at which the fluorescence signal intersects a predetermined threshold line. In standard curve methodology, the optimal threshold is typically selected automatically by identifying the position that yields the maximum coefficient of determination (r²) for the standard curve, often exceeding 99% [7]. The standard curve itself is generated by performing linear regression on the plot of CP values against the logarithm of known template concentrations for the dilution series.

The statistical assessment of intra-assay variation is a critical advantage of this approach. Means and variances are calculated for CP values in PCR replicates, and these variances are propagated through subsequent calculations using error propagation principles, providing confidence intervals for final quantitative results [7].

Comparative Performance: qPCR vs. dPCR for Mutant Allele Detection

In the context of detecting mutant alleles, particularly for cancer research and personalized medicine applications, the limitations and strengths of qPCR become apparent when compared with digital PCR (dPCR). The following table summarizes key performance characteristics based on experimental data:

Table 1: Performance comparison between qPCR and dPCR for mutant allele detection

| Performance Characteristic | qPCR (ARMS-based) | Droplet Digital PCR (dPCR) | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | ~1% mutation rate [9] | ≤0.1% mutation rate [9] [10] | EGFR T790M mutation detection in plasmid samples [9] |

| Quantification Type | Relative (requires standard curve) [10] [8] | Absolute (no standard curve needed) [9] [10] | Direct comparison using identical samples [9] |

| Dynamic Range | Broad [11] | Limited by partition number [11] | Detection of Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri [11] |

| Precision at Low Concentration | Higher CV (coefficient of variation) [11] | Lower CV, especially at low target concentration [11] | Pathogen quantification in plant samples [11] |

| Tolerance to PCR Inhibitors | Moderate [10] | High (due to sample partitioning) [10] | Analysis of environmental and clinical samples [10] [11] |

| Practical Agreement | 91.7% overall agreement with dPCR [12] | Reference method for discordant samples [9] [12] | EGFR T790M detection in clinical NSCLC samples [12] |

Experimental Evidence in Mutant Allele Detection

The comparative performance of qPCR and dPCR has been extensively evaluated in mutation detection studies, particularly for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In one study comparing amplification refractory mutation system-based qPCR (ARMS-qPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) for detecting EGFR T790M mutation, the ARMS-qPCR method reliably detected plasmid samples with 5% and 1% mutation rates, while ddPCR consistently detected mutation rates as low as 0.1% (approximately 6 mutant copies in 6,000 wild-type copies) [9].

Clinical validation using 10 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples from NSCLC patients revealed concordance in 9 samples between the two methods. Notably, sample N006, identified as EGFR wild-type by ARMS-qPCR, was shown to harbor a clear EGFR T790M mutation using ddPCR technology, with 7 copies of mutant alleles detected against a background of 6,000 wild-type copies [9]. This demonstrates ddPCR's superior sensitivity for detecting low-abundance mutations in clinical samples, which is crucial for early detection of resistance mutations during tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy.

A larger study of 72 NSCLC patients comparing QuantStudio 3D dPCR and droplet dPCR for detecting T790M mutation in cell-free DNA found 91.7% overall agreement (66/72 samples). The 6 discordant samples showed low mutation abundance (~0.1%), with the discrepancy attributed to stricter threshold settings for QS3D dPCR [12].

Methodological Protocols for qPCR Calibration Curve Assays

Standard Curve Generation Protocol

The following diagram outlines the experimental workflow for establishing a qPCR calibration curve:

The standard curve generation begins with preparation of a serial dilution series of known template concentration, typically spanning 5-6 orders of magnitude (e.g., 10-fold dilutions). The template can be purified PCR product, plasmid DNA constructs, or synthetic oligonucleotides spanning the PCR amplicon [8]. Each dilution should be amplified in multiple replicates (typically 3+ replicates) to account for technical variability.

During the qPCR run, fluorescence data is collected at each cycle. Following amplification, the raw fluorescence data undergoes processing as described in Section 2.1. The optimal threshold for Cq determination is selected to maximize the coefficient of determination (r²) of the standard curve [7]. Linear regression of Cq values versus the logarithm of initial template concentrations generates the standard curve equation, from which amplification efficiency is calculated [8].

Advanced Calibration Approaches

Recent methodological advances have addressed limitations in traditional standard curve approaches. The Pairwise Efficiency method represents a novel mathematical approach to qPCR data analysis that improves the precision of calibration curve assays. This method uses a modified formula describing pairwise relationships between data points on separate amplification curves from a dilution series, enabling extensive statistical analysis. Compared to the standard calibration curve method, Pairwise Efficiency demonstrates nearly double the precision in qPCR efficiency determinations and a 2.3-fold improvement in precision of gene expression ratio estimations using the same experimental dataset [13].

For applications requiring correction of variations in amplification efficiency between standards and samples, the One-Point Calibration (OPC) method has been developed. This approach corrects for efficiency differences and has shown superior accuracy compared to the standard curve method when quantifying artificial template mixtures with differing amplification efficiencies. In validation studies, while the standard curve method deviated from the expected nifH gene copy number by 3- to 5-fold, the OPC method quantified template mixtures with high accuracy [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for qPCR calibration curve assays

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Template | Provides known concentration reference for standard curve | Purified PCR product, plasmid DNA, or synthetic oligonucleotides; must span the amplicon [8] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains enzymes, dNTPs, buffer for amplification | SYBR Green or probe-based; optimized for efficiency [7] |

| Primer Pairs | Sequence-specific amplification | Designed for target specificity; optimal GC content [14] |

| Probe (if applicable) | Sequence-specific detection | Hydrolysis (TaqMan) or hybridization formats; FAM-labeled common [8] |

| Nuclease-free Water | Reaction reconstitution | Free of contaminants and nucleases |

| qPCR Plates/Tubes | Reaction vessel | Optically clear; compatible with instrument [9] |

| Sealing Materials | Prevents evaporation | Optical seals or caps [7] |

| Positive Control | Assay validation | Known positive sample for quality control |

| No Template Control (NTC) | Contamination check | Water instead of template; should not amplify [9] |

The qPCR calibration curve method remains a fundamental tool for nucleic acid quantification, providing a reliable approach for relative quantification in gene expression analysis and mutation detection. While the method is well-established and widely used, its limitations in detecting very low-abundance mutations (<1%) have become apparent in applications requiring high sensitivity, such as cancer resistance mutation monitoring. The emergence of digital PCR platforms offers complementary capabilities with absolute quantification and enhanced sensitivity for rare variant detection.

The continuing development of improved calibration methods, such as Pairwise Efficiency and One-Point Calibration, demonstrates that innovation in qPCR methodology remains active. For researchers and clinical diagnosticians, the choice between qPCR and dPCR technologies depends on the specific application requirements, with qPCR maintaining advantages in dynamic range and established workflows, while dPCR provides superior sensitivity for low-abundance targets and absolute quantification without standard curves.

Digital PCR (dPCR) represents a significant advancement in nucleic acid quantification, enabling the absolute detection and measurement of target DNA sequences without reliance on standard curves. This technology's core principles—sample partitioning, end-point analysis, and Poisson statistical analysis—provide unmatched precision for applications requiring high sensitivity, particularly in detecting rare mutant alleles in cancer research and liquid biopsies. This guide explores the fundamental mechanics of dPCR and provides an objective comparison with quantitative PCR (qPCR) through experimental data, offering researchers a comprehensive resource for selecting appropriate molecular detection methods.

Digital PCR (dPCR) has emerged as a powerful technique for absolute quantification of nucleic acids, operating on three fundamental principles: sample partitioning, end-point detection, and Poisson statistics [15]. Unlike quantitative PCR (qPCR) that measures amplification in real-time relative to standard curves, dPCR physically partitions a sample into thousands to millions of individual reactions where amplification occurs independently [16]. This partitioning process effectively dilutes the template molecules such that each partition contains either zero, one, or a few target molecules [15]. Following PCR amplification to endpoint, each partition is analyzed for the presence or absence of a fluorescent signal, with positive partitions indicating the presence of at least one target molecule [17]. The binary data generated (positive/negative partitions) is then subjected to Poisson statistical analysis to calculate the absolute concentration of the target sequence in the original sample [18]. This mechanistic approach provides dPCR with significant advantages for detecting low-abundance targets and achieving precise quantification without external references.

The application of dPCR has become particularly valuable in fields requiring high sensitivity and precision, such as cancer research and liquid biopsy analysis, where it can detect rare mutations with mutant allele frequencies as low as 0.1% [19]. Additionally, dPCR has demonstrated superior performance in viral load quantification and copy number variation analysis, often outperforming traditional qPCR in reproducibility and resistance to PCR inhibitors [6] [16]. As research continues to demand higher sensitivity for detecting rare mutations and quantifying slight genetic variations, understanding the core mechanics of dPCR becomes essential for selecting appropriate molecular detection methods.

Core Mechanical Principles of dPCR

Sample Partitioning Strategies

The foundation of dPCR lies in its ability to partition a single PCR reaction into numerous individual reactions, a process achieved through different technological approaches:

Droplet-based Partitioning (ddPCR): This method utilizes microfluidics to partition the sample into thousands to millions of nanoliter-sized oil-emulsion droplets [15] [20]. The QX200 droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) system from Bio-Rad represents this approach, where each droplet functions as an individual PCR microreactor [18]. The random distribution of template molecules into droplets follows Poisson distribution, with most droplets containing either zero or one template molecule at appropriate dilutions.

Chip-based/Nanoplate-based Partitioning (cdPCR): This alternative approach employs microfluidic chips with fixed nanowells or microchambers to partition the sample [15] [20]. Systems like the QIAcuity from QIAGEN use nanoplate technology with approximately 26,000 individual wells [6] [18], while the QuantStudio Absolute Q system utilizes microfluidic array plates (MAP) technology [19]. These systems offer simplified workflows by integrating partitioning and thermal cycling into single steps.

The partitioning process effectively enriches low-abundance targets by separating them from abundant background DNA, significantly enhancing detection sensitivity for rare alleles [21] [19]. The number of partitions directly impacts precision, with higher partition counts providing better statistical confidence and lower detection limits [18].

End-Point Analysis and Detection

Following partitioning and thermal cycling, dPCR employs end-point detection to analyze each partition:

Fluorescence Detection: After PCR amplification is complete, each partition is analyzed for fluorescence using either laser scanning or imaging systems [18]. Probe-based chemistries (such as TaqMan probes) are typically used, with different fluorescent labels for various targets enabling multiplexing capabilities [19].

Signal Classification: Partitions are classified as positive or negative based on their fluorescence intensity exceeding a predetermined threshold [17]. This binary classification is fundamental to the digital nature of the technology, enabling absolute quantification without reference to amplification kinetics [16].

Real-time dPCR Enhancement: Recent advancements have introduced real-time dPCR, which collects amplification data throughout the thermal cycling process rather than just at endpoint [5]. This approach enables the identification and elimination of false positive signals based on their atypical amplification profiles, further improving detection sensitivity and accuracy, particularly for rare allele detection [5].

Poisson Statistics and Absolute Quantification

The mathematical foundation of dPCR relies on Poisson statistics to calculate target concentration from the binary partition data:

Principle of Poisson Distribution: Poisson statistics account for the random distribution of template molecules across partitions [15] [18]. The model assumes that template molecules follow a Poisson distribution during partitioning, meaning some partitions will contain multiple copies while others contain none or one.

Concentration Calculation: The fundamental Poisson equation used in dPCR is: [ C = -\ln(1 - p) \times V^{-1} ] Where (C) is the target concentration, (p) is the proportion of positive partitions, and (V) is the partition volume [18]. This calculation provides absolute quantification without standard curves, a significant advantage over qPCR.

Limitations and Considerations: The accuracy of Poisson statistics depends on having sufficient partitions and appropriate template dilution to avoid saturation effects [18]. When too many partitions are positive (typically >90%), the Poisson model becomes less accurate due to an increasing number of partitions containing multiple template molecules [16].

Table 1: Comparison of dPCR Partitioning Technologies

| Feature | Droplet-based (ddPCR) | Chip/Nanoplate-based (cdPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Partition Mechanism | Oil-emulsion droplets | Fixed nanowells/microchambers |

| Typical Partition Count | 20,000 (QX200) [18] | 26,000 (QIAcuity) [6] |

| Throughput | Moderate | High with automation |

| Reaction Assembly | Separate partitioning step | Integrated partitioning and cycling |

| Detection Method | Flow cytometry | Imaging |

Experimental Comparison: dPCR vs qPCR for Mutant Allele Detection

Methodology for Performance Comparison

To objectively evaluate the performance of dPCR against qPCR for detecting mutant alleles, we designed a comparative analysis based on published experimental approaches:

Sample Preparation: Contrived samples were prepared using mixed genomic DNA from wild-type and mutant cell lines to simulate clinical samples with known mutant allele frequencies (MAF) [5]. For EGFR mutation detection, DNA from mutant cell lines (NCI-H1975 for T790M and L858R; HCC827 for exon 19 deletions) was mixed with wild-type human genomic DNA at varying ratios [5].

Instrumentation and Platforms: Experiments compared leading dPCR systems including the QIAcuity One nanoplate-based system (QIAGEN) and QX200 droplet-based system (Bio-Rad) against standard qPCR platforms [6] [18]. The novel real-time dPCR system was also evaluated against endpoint dPCR for rare allele detection [5].

Data Analysis: For dPCR, absolute quantification was performed using Poisson statistics [18]. qPCR analysis utilized standard curve-based quantification with serial dilutions of known standards [16]. Sensitivity, specificity, limit of detection (LOD), and precision were calculated for both technologies across multiple replicates.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for dPCR Mutation Detection

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| Digital PCR System | Partitioning, amplification, and detection | QIAcuity One, QX200 ddPCR, QuantStudio Absolute Q |

| Assay Kits | Target-specific detection | Absolute Q Liquid Biopsy dPCR Assays [19] |

| Master Mix | PCR reagents and enzymes | dPCR-specific master mixes with optimized buffers |

| Restriction Enzymes | Improve DNA accessibility | HaeIII, EcoRI (for complex genomes) [18] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Sample preparation | MagMax Viral/Pathogen kit [6] |

Quantitative Performance Data

Experimental results demonstrate distinct performance characteristics between dPCR and qPCR technologies:

Sensitivity and Limit of Detection: dPCR consistently shows superior sensitivity for rare allele detection. In respiratory virus detection, dPCR demonstrated significantly improved accuracy for high viral loads of influenza A, influenza B, and SARS-CoV-2, and for medium loads of RSV [6]. For EGFR mutation detection, real-time dPCR achieved a lower limit of detection compared to endpoint dPCR, requiring only 2 positive partitions for positive calling compared to 5 for endpoint systems [5].

Precision and Reproducibility: dPCR exhibits enhanced precision, particularly at low target concentrations. A comparative study of dPCR platforms found coefficient of variation (CV) values below 5% for optimal systems, with generally higher precision observed when using specific restriction enzymes like HaeIII instead of EcoRI [18]. This precision advantage is most pronounced at low template concentrations where qPCR variability increases substantially.

Quantification Accuracy: dPCR provides more accurate quantification at low allele frequencies. For EGFR mutations, real-time dPCR generated mutant allele frequencies closer to expected values at very low MAF compared to endpoint dPCR [5]. However, at high target concentrations or for gene amplification assays, both technologies show comparable performance [5].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of dPCR vs qPCR for Mutation Detection

| Parameter | Digital PCR | Quantitative PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | 0.1% mutant allele frequency [19] | Typically 1-5% mutant allele frequency |

| Quantification Method | Absolute (Poisson statistics) | Relative (standard curve required) |

| Precision at Low Concentration | CV: 5-13% [18] | CV: 15-25% or higher |

| Impact of Inhibitors | Reduced effect due to partitioning [16] | Significant impact on amplification efficiency |

| Dynamic Range | Limited at high concentrations [16] | Broad with optimized assays |

| Multiplexing Capability | Moderate (2-5 plex) [6] | High with different reporter dyes |

dPCR Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for digital PCR analysis, from sample preparation through data interpretation:

Diagram 1: dPCR Experimental Workflow. Key distinguishing steps of dPCR (partitioning, binary classification, and Poisson analysis) are highlighted.

Discussion and Technical Considerations

Applications and Practical Implementation

The mechanical principles of dPCR make it particularly suitable for specific research applications:

Rare Mutation Detection: dPCR's partitioning mechanics enable detection of rare mutations down to 0.1% allele frequency, making it invaluable for liquid biopsy applications in oncology [19] [5]. The technology can identify emerging resistance mutations (e.g., EGFR T790M) and monitor minimal residual disease with sensitivity exceeding qPCR.

Copy Number Variation (CNV) Analysis: dPCR provides absolute quantification for precise CNV determination without reference standards, offering advantages over qPCR for detecting subtle copy number differences [15] [18].

Viral Load Quantification: dPCR's absolute quantification capability improves accuracy in viral load measurements, as demonstrated in respiratory virus studies where it outperformed qPCR across different viral load categories [6].

Limitations and Practical Challenges

Despite its advantages, dPCR presents several practical limitations:

Throughput and Cost: dPCR typically has lower throughput and higher per-sample cost compared to qPCR, making it less suitable for high-volume screening [16] [17]. The specialized equipment and consumables contribute to higher operational costs.

Dynamic Range Limitations: While excellent for low-abundance targets, dPCR has a more limited dynamic range at high target concentrations due to partition saturation effects [16] [18].

Technical Complexity: The requirement for partitioning and more complex data analysis presents a steeper learning curve compared to qPCR, though newer integrated systems are addressing this challenge [19].

The core mechanics of dPCR—sample partitioning, end-point analysis, and Poisson statistics—provide a fundamentally different approach to nucleic acid quantification compared to traditional qPCR. This mechanistic foundation enables absolute quantification without standard curves and superior sensitivity for rare target detection. Experimental data consistently demonstrates dPCR's advantages for applications requiring high precision at low concentrations, particularly in mutant allele detection for cancer research.

For researchers investigating rare mutations or requiring absolute quantification, dPCR offers significant performance benefits despite its higher cost and lower throughput. Continued technological advancements, including real-time dPCR and improved multiplexing capabilities, are further expanding dPCR's applications in both research and clinical diagnostics. The choice between dPCR and qPCR ultimately depends on specific application requirements, with dPCR representing the optimal tool for challenging detection scenarios where sensitivity and precision are paramount.

Digital PCR (dPCR) represents a fundamental shift in nucleic acid quantification from quantitative PCR (qPCR). While qPCR relies on relative quantification by comparing the amplification cycle number (Cq) to a standard curve, dPCR provides absolute quantification by partitioning a sample into thousands of individual reactions and applying Poisson statistics to count target molecules directly [11] [22]. This core difference in methodology underlies the significant performance advantages dPCR offers for detecting rare mutant alleles, particularly in applications like liquid biopsy and oncogene monitoring where sensitivity and precision are paramount [9] [22].

The partitioning process in dPCR enables single-molecule detection, making it possible to identify rare mutations present at very low abundances within a background of wild-type sequences [22]. This technical advancement has positioned dPCR as a crucial tool in precision medicine, where early detection of treatment resistance mutations can inform clinical decisions before acquired resistance becomes clinically evident [9].

Comparative Performance Metrics

Direct comparisons between dPCR and qPCR across multiple studies reveal consistent patterns of performance differences in key metrics essential for mutant allele detection.

Table 1: Direct Performance Comparison between dPCR and qPCR

| Performance Metric | Digital PCR Performance | Quantitative PCR Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Detects EGFR T790M mutations at 0.1% mutation rate [9] | Requires ≥1% mutation rate for reliable detection [9] | Plasmid DNA samples with defined mutation rates [9] |

| Precision | Intra-assay CV: 4.5% (periodontal pathobionts) [23] | Higher intra-assay variability than dPCR (p=0.020) [23] | Subgingival plaque samples from periodontitis patients [23] |

| Dynamic Range | Broader dynamic range for Xanthomonas citri detection [11] | Good linearity but narrower dynamic range [11] | Plant pathogen detection in citrus crops [11] |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | Reduced susceptibility to PCR inhibitors [11] | More significantly affected by inhibitors [11] | Analysis of plant-derived inhibitors in environmental samples [11] |

| Limit of Detection | 0.17 copies/μL (QX200 ddPCR) [18] | Higher detection limits, varies by assay [11] | Synthetic oligonucleotide dilutions [18] |

| Limit of Quantification | 4.26 copies/μL (QX200 ddPCR) [18] | Higher quantification limits [9] | Synthetic oligonucleotide dilutions [18] |

Sensitivity and Limit of Detection

dPCR demonstrates substantially superior sensitivity for detecting low-abundance targets. In a landmark study comparing EGFR T790M mutation detection, dPCR reliably identified mutations at 0.1% mutation rates (approximately 6 mutant copies among 6,000 wild-type copies), while the ARMS-qPCR method required 1-5% mutation rates for stable detection [9]. This enhanced sensitivity has direct clinical relevance, as researchers identified one clinical sample (N006) with a clear T790M mutation using dPCR that was classified as wild-type by ARMS-qPCR [9].

This sensitivity advantage extends beyond oncology applications. In periodontal microbiology, dPCR demonstrated superior detection of low bacterial loads, particularly for P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans, resulting in qPCR false negatives at concentrations below 3 log₁₀ genomic equivalents/mL [23]. The fundamental partitioning approach enables dPCR to detect single molecules, with studies reporting limits of detection as low as 0.17 copies/μL for the QX200 ddPCR system [18].

Precision and Reproducibility

dPCR exhibits significantly better precision, especially at low target concentrations. In periodontal pathogen quantification, dPCR showed lower intra-assay variability (median CV: 4.5%) compared to qPCR [23]. This precision advantage is most pronounced near the detection limit, where qPCR results typically show higher coefficients of variation [11].

Precision in dPCR is influenced by platform choice and experimental conditions. A 2025 study comparing the QX200 droplet dPCR and QIAcuity One nanoplate dPCR found both platforms provided high precision, though performance varied with restriction enzyme selection [18]. When using the HaeIII restriction enzyme, the QX200 system achieved exceptional precision with all CV values below 5% across various cell numbers of Paramecium tetraurelia [18].

Dynamic Range

The dynamic range characteristics of dPCR and qPCR differ significantly. While qPCR typically demonstrates a broader dynamic range in some applications [11], dPCR provides excellent linearity across its effective range. One study reported high linearity (R² > 0.99) for dPCR across measurable concentrations [23].

A key consideration in dPCR analysis is the optimal partition occupancy rate. According to Poisson statistics, the optimal range for accurate quantification is between 0.1 and 5 copies per partition [22]. Beyond approximately 6-7 copies per partition, saturation effects occur, reducing quantification accuracy. This fundamental limitation defines the effective dynamic range of dPCR systems, though sample dilution can extend the measurable range.

Tolerance to PCR Inhibitors

dPCR demonstrates superior tolerance to PCR inhibitors commonly found in clinical and environmental samples. In plant pathogen detection, the influence of PCR inhibitors was "considerably reduced" in dPCR compared to qPCR assays [11]. This advantage stems from the partitioning process, which effectively dilutes inhibitors across thousands of individual reactions, reducing their local concentration and minimizing interference with amplification [22].

The endpoint measurement approach in dPCR also contributes to its resilience against inhibitors. Unlike qPCR, which depends on the efficiency of amplification throughout all cycles, dPCR only requires sufficient amplification to generate a fluorescent signal above background in positive partitions, making it less vulnerable to inhibitors that reduce amplification efficiency [11].

Experimental Protocols for Performance Validation

Protocol for Sensitivity and Limit of Detection Determination

To evaluate detection sensitivity for mutant alleles, researchers can employ plasmid models with defined mutation rates:

- Plasmid Standard Preparation: Construct plasmid standards containing wild-type and mutant sequences (e.g., EGFR T790M). Create dilution series with defined mutation rates (0.1%, 0.5%, 1%, 5%) by mixing mutant and wild-type plasmids [9].

- Sample Processing: Adjust templates to a unified concentration (e.g., 10 ng/μL). For dPCR, prepare 25 μL reactions using 2X Master Mix, primer-probe mix, and template [9].

- Partitioning and Amplification: For ddPCR, generate droplets using a droplet generator cartridge. Thermal cycling conditions: 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds and 58°C for 1 minute, then 98°C for 10 minutes [9].

- Data Analysis: Calculate mutant allele frequency using Poisson statistics from positive and negative partitions [22].

Protocol for Precision Assessment

Method for determining inter-assay and intra-assay precision:

- Sample Preparation: Use synthetic oligonucleotides or DNA extracted from reference cell lines. Prepare replicate samples across multiple runs [18].

- Experimental Design: For intra-assay precision, analyze multiple replicates within the same run. For inter-assay precision, analyze replicates across different runs, days, or operators [23].

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate coefficient of variation (CV%) for replicate measurements. Apply statistical frameworks like Generalized Linear Models (GLM) or Multiple Ratio Tests (MRT) for comparing multiple dPCR experiments [24].

Protocol for Inhibitor Tolerance Evaluation

Assessing inhibitor resistance using environmental or clinical samples:

- Sample Collection: Collect samples with inherent inhibitors (e.g., plant tissues, FFPE samples, blood) [11].

- Inhibitor Spiking: Add known PCR inhibitors (humic acids, heparin, IgG) to purified DNA samples in increasing concentrations [11].

- Parallel Analysis: Process identical samples with dPCR and qPCR simultaneously. For dPCR, use 40 μL reactions with restriction enzymes if needed to improve DNA accessibility [23] [18].

- Quantification Comparison: Compare quantification results between platforms, noting the concentration at which qPCR fails while dPCR continues to provide accurate quantification [11].

dPCR Platform Comparisons

Different dPCR platforms exhibit distinct performance characteristics that researchers should consider when selecting instrumentation.

Table 2: Comparison of dPCR Platforms and Technologies

| Platform/Technology | Partitioning Method | Key Advantages | Typical Partitions | Optimal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet dPCR | Water-in-oil emulsion [22] | High partition count, well-established | Up to 20,000 partitions [9] | High sensitivity applications, rare variant detection [9] |

| Nanoplate dPCR | Microfabricated chips [22] | Simplified workflow, reduced cross-contamination | ~26,000 partitions [23] | Routine clinical tests, multiplex applications [23] |

| BEAMing Technology | Emulsion with magnetic beads [22] | Combination with flow cytometry, high multiplexing | Variable | Rare cell detection, single-cell analysis [22] |

| Microfluidic Chip | Fixed microchambers [22] | Excellent reproducibility, consistent volumes | Thousands to millions [22] | Regulatory applications, lot release testing [25] |

A 2025 comparative study of the QX200 ddPCR (Bio-Rad) and QIAcuity One nanoplate dPCR (QIAGEN) systems found both platforms demonstrated similar detection and quantification limits with high precision across most analyses [18]. The QX200 system showed a limit of detection of approximately 0.17 copies/μL, while the QIAcuity system's LOD was approximately 0.39 copies/μL [18]. However, precision was influenced by restriction enzyme selection, with HaeIII providing better precision than EcoRI, especially for the QX200 system [18].

Application Workflows for Mutant Allele Detection

The detection of rare mutant alleles follows a structured workflow that leverages dPCR's strengths in partitioning and absolute quantification.

Figure 1: dPCR Workflow for Mutant Allele Detection

This workflow enables researchers to detect rare mutations with unparalleled sensitivity. In liquid biopsy applications for oncology, the process begins with cell-free DNA extraction from blood plasma, followed by dPCR reaction setup with mutation-specific probes [9] [12]. After partitioning and amplification, the analysis phase applies Poisson statistics to calculate mutant allele frequency, enabling detection of mutations present at frequencies as low as 0.1% [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful dPCR experiments require carefully selected reagents and optimized reaction conditions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for dPCR Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance | Optimization Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit [9], QIAamp DNA Mini Kit [23] | Obtain high-quality template DNA free of inhibitors | Ensure appropriate elution volume for target concentration [9] |

| dPCR Master Mixes | ddPCR 2X Master Mix [9], QIAcuity Probe PCR Kit [23] | Provide optimized buffer, enzymes, dNTPs for partitioning | Include restriction enzymes (e.g., HaeIII) for complex genomes [18] |

| Primers & Probes | TaqMan hydrolysis probes [9], Target-specific primers [23] | Enable specific detection of mutant vs. wild-type alleles | Optimize concentrations (e.g., 0.4μM primers, 0.2μM probes) [23] |

| Reference Assays | Reference genes (e.g., for total DNA quantification) [9] | Normalize for DNA input quantity and quality | Select reference targets with similar amplification efficiency [9] |

| Partitioning Reagents | Droplet Generation Oil [9], Nanoplate seals [23] | Create stable partitions for individual reactions | Ensure proper storage and handling to maintain partition integrity [9] |

Digital PCR demonstrates clear advantages over qPCR for detecting mutant alleles across all four key performance metrics. The technology provides superior sensitivity for rare variant detection, enhanced precision especially at low target concentrations, excellent linearity across its dynamic range, and greater resilience to PCR inhibitors. These performance characteristics make dPCR particularly valuable for applications requiring absolute quantification of rare mutations, such as liquid biopsy monitoring of cancer treatment resistance [9], early pathogen detection [23], and environmental monitoring [11].

While dPCR may have a more limited dynamic range compared to qPCR and requires specialized instrumentation, its performance benefits justify the adoption in research and clinical settings where detection of low-abundance targets is critical. As dPCR technology continues to evolve with improvements in multiplexing capabilities, workflow automation, and data analysis tools, its application in mutant allele detection is expected to expand further, potentially enabling new approaches in precision medicine and molecular diagnostics [25] [22].

For researchers detecting mutant alleles, the choice between quantitative PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR) often comes down to a fundamental question: should results be interpreted through the Cycle Threshold (Ct), a relative and indirect measure, or the absolute copies/μL, a direct count of target molecules? This guide provides an objective comparison of these two quantification methods and the technologies that produce them.

Core Concepts: Ct and Copies/μL Defined

What is Cycle Threshold (Ct)?

In quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), the Cycle Threshold (Ct) value is the PCR cycle number at which the amplification curve of a target sequence crosses a fluorescence threshold set above the background level [26] [27]. This value is inversely proportional to the starting amount of the target nucleic acid: a lower Ct value indicates a higher initial target concentration, while a higher Ct value indicates a lower concentration [26] [28].

Crucially, the Ct value is a relative measure. To convert a Ct value into a concentration, a standard curve with samples of known concentrations must be run alongside the experimental samples [28]. The quantitative relationship is described by the formula: Quantity ≈ e-Ct, where 'e' represents the amplification efficiency [26].

What is Copies/μL?

Copies per microliter (copies/μL) is a unit of absolute quantification. It represents the exact number of target DNA or RNA molecules present in a given volume of sample [22]. This measurement is the primary output of digital PCR (dPCR).

dPCR achieves this by partitioning a PCR reaction into thousands of individual nanoreactions. After amplification, the platform counts the number of partitions that contain the target sequence (positive partitions) and applies Poisson statistics to calculate the absolute concentration in the original sample, without the need for a standard curve [6] [22].

Technology Face-Off: qPCR vs. dPCR

The following table summarizes the fundamental differences between the two technologies that generate Ct values and copies/μL.

| Feature | Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) | Digital PCR (dPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Type | Relative (requires standard curve) | Absolute (no standard curve) |

| Primary Output | Cycle Threshold (Ct) | Copies/μL |

| Principle | Monitors amplification in real-time | Partitions sample, uses end-point detection & Poisson statistics |

| Sensitivity & Precision | High | Superior, especially for low-abundance targets and rare mutations [6] [29] |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | Moderate | High [30] |

| Throughput & Cost | High throughput, lower cost per sample | Lower throughput, higher cost per sample [6] |

| Ideal For | High-throughput screening, gene expression (relative), well-established diagnostic assays | Absolute quantification, rare allele detection (e.g., ctDNA, minor clones), copy number variation [29] [31] |

Experimental Performance in Mutant Allele Detection

Detection of JAK2V617F Mutation in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms

A 2025 study optimized a laboratory-developed droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) assay for the JAK2V617F mutation, a critical biomarker for MPNs [29].

- Methodology: The assay was optimized by fine-tuning five key parameters: primer/probe sequences and concentrations, annealing temperature, template amount, and PCR cycles [29].

- Key Finding on LoQ: The optimized ddPCR assay demonstrated an exceptional limit of quantification (LoQ) of 0.01% variant allele frequency (VAF). This means it could reliably quantify the mutant allele even when it constituted just 0.01% of the total DNA background, a level of sensitivity crucial for early detection and monitoring minimal residual disease [29].

Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Detection in Rectal Cancer

A 2025 comparative study directly pitted ddPCR against Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for detecting ctDNA in non-metastatic rectal cancer [31].

- Methodology: Pre-therapy plasma and tumor samples were collected from 41 patients. Mutations were identified in tumor tissue via NGS, and ctDNA detection in plasma was performed using both ddPCR and an NGS panel [31].

- Key Finding on Sensitivity: In the development group, ddPCR detected ctDNA in 58.5% (24/41) of baseline plasma samples, significantly outperforming the NGS panel, which detected ctDNA in only 36.6% (15/41). This highlights ddPCR's superior sensitivity for detecting low-frequency mutations in a background of wild-type DNA, a common challenge in liquid biopsy applications [31].

General Workflow Comparison for Inhibitor Tolerance

While not specific to mutant alleles, a key technical advantage of dPCR is its resilience to PCR inhibitors, which can severely impact qPCR accuracy [30].

- Principle: In qPCR, inhibitors present in the sample reduce the effective amplification efficiency, leading to higher Ct values and an underestimation of the true target concentration. In dPCR, because the sample is partitioned, the inhibitor molecules are also distributed. While some partitions may be affected, many others will amplify normally, preserving the accuracy of the absolute count derived from the ratio of positive to negative partitions [30].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and reagents required for implementing qPCR and dPCR workflows in a research setting.

| Item | Function in qPCR/dPCR |

|---|---|

| Primers & Probes | Target-specific oligonucleotides that define the sequence to be amplified. Fluorogenic probes (e.g., TaqMan) are essential for specific detection in both qPCR and dPCR [26]. |

| Thermostable DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that catalyzes DNA synthesis. Hot-start enzymes are preferred to prevent non-specific amplification during reaction setup [32] [33]. |

| dNTP Mix | Deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP); the building blocks for new DNA strands [32]. |

| Reaction Buffer | Provides optimal chemical environment (pH, salts) for polymerase activity. MgCl₂ concentration is a critical component [33]. |

| dPCR Partitioning Oil/Chips | For ddPCR, this immiscible oil creates the droplet partitions. For systems like QIAcuity, microchamber chips are used [6] [22]. |

| Nucleic Acid Isolation Kits | For purification of high-quality DNA/RNA from samples (e.g., tumor tissue, blood). Purity is especially critical for qPCR accuracy [27] [29]. |

| Standard Curve Materials | For qPCR absolute quantification, a serial dilution of a sample with known concentration (e.g., gBlocks, plasmid DNA) is essential [28]. |

The choice between relying on Ct values from qPCR or copies/μL from dPCR hinges on the specific requirements of your research on mutant alleles.

- Use qPCR/Ct when your project involves high-throughput sample screening, relative quantification (e.g., gene expression fold-changes) is sufficient, and the target is not extremely rare. Its lower cost and established workflows are key advantages [6] [30].

- Choose dPCR/copies/μL when your goal is the absolute quantification of rare mutations (e.g., in liquid biopsy), precise measurement of copy number variations, or when working with complex samples that may contain PCR inhibitors. Its superior sensitivity, precision, and lack of reliance on a standard curve make it the superior tool for these demanding applications [6] [29] [31].

For drug development and clinical research, where accurately quantifying minor mutant clones or tracking minute changes in allele frequency can be critical for patient stratification and therapy monitoring, dPCR offers a level of performance that is often unmatched by traditional qPCR.

Targeted Applications: Implementing dPCR and qPCR in Mutant Allele Workflows

The detection of rare alleles, such as somatic mutations in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), is a significant challenge in molecular diagnostics and oncology research. While quantitative PCR (qPCR) has been the traditional method for nucleic acid quantification, digital PCR (dPCR) offers a transformative approach through sample partitioning. This guide objectively compares the performance of dPCR and qPCR for rare mutant allele detection, supported by experimental data demonstrating dPCR's superior sensitivity, precision, and ability for absolute quantification without standard curves. We detail specific methodologies that leverage dPCR's partitioning advantage to achieve detection sensitivities as low as 0.001% mutant allele frequency, enabling applications in liquid biopsy, cancer monitoring, and pathogen detection.

Accurate detection of low-abundance nucleic acid targets is crucial across biomedical research and clinical diagnostics. In oncology, for example, rare mutant alleles can indicate early cancer development, minimal residual disease, or emerging therapy-resistant subclones [22] [34]. These targets often appear at frequencies below 0.1% amidst a background of wild-type sequences, presenting a formidable detection challenge [35].

Traditional qPCR quantifies nucleic acids by measuring amplification fluorescence in real-time, with target concentration determined by the cycle threshold (Ct) relative to standard curves. While excellent for higher abundance targets, qPCR encounters sensitivity limitations at very low target concentrations due to background noise and amplification efficiency variations [36] [16].

Digital PCR addresses these limitations through a fundamental methodological shift: partitioning the sample into thousands of nanoscale reactions. This allows individual mutant molecules to be detected against the wild-type background, providing absolute quantification and dramatically enhancing sensitivity for rare allele detection [36] [22].

Technological Comparison: Partitioning as a Key Differentiator

Fundamental Working Principles

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) amplifies DNA in a bulk reaction, monitoring fluorescence accumulation during cycling. The cycle threshold (Ct) at which fluorescence crosses a background level correlates with initial DNA concentration, requiring standard curves for quantification [36] [16]. This approach works well for abundant targets but struggles with rare variants where signal differences are minimal.

Digital PCR (dPCR) incorporates a crucial partitioning step before amplification. The reaction mixture is divided into numerous individual partitions—either droplets or microchambers—so that each contains zero, one, or a few target molecules. Following end-point PCR amplification, partitions are scored as positive or negative based on fluorescence. The absolute target concentration is calculated using Poisson statistics based on the ratio of positive to negative partitions, eliminating the need for standard curves [22] [18].

Direct Performance Comparison

The partitioning methodology of dPCR provides distinct advantages for rare allele detection, as summarized in the performance comparison below.

Table 1: Performance comparison between qPCR and dPCR for rare allele detection

| Feature | qPCR (Quantitative PCR) | dPCR (Digital PCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Type | Relative (requires standard curve) | Absolute (no standard curve needed) |

| Sensitivity | High, but limited by background noise | Ultra-high, ideal for low-abundance targets |

| Precision & Reproducibility | Good, affected by PCR efficiency variations | Excellent, due to absolute quantification |

| Dynamic Range | 7–10 logs | 5 logs |

| Error Susceptibility | More variation due to amplification efficiency | Low error rate, robust for complex samples |

| Ideal Application | Gene expression, high-throughput pathogen detection | Rare mutation detection, copy number variation, liquid biopsy |

Partitioning enables dPCR's superior performance by effectively enriching mutant signals. When a sample containing rare mutants is partitioned, reactions containing mutant molecules become concentrated sources of mutant DNA after amplification, while the vast majority containing only wild-type sequences remain distinct. This physical separation prevents amplification competition and background interference that plagues bulk reactions in qPCR [37] [35].

Experimental Evidence: Quantifying dPCR Sensitivity

Sensitivity Limits for Cancer Mutations

Multiple studies have rigorously quantified dPCR's detection limits for clinically relevant mutations. In one comprehensive evaluation of EGFR mutations, dPCR demonstrated exceptional sensitivity with a false-positive rate of just 1 in 14 million molecules. The lower limit of detection (LoD) reached 1 mutant in 180,000 wild-type molecules (0.00056%) when analyzing 3.3 μg of genomic DNA. When processing larger DNA quantities (70 million copies), detection sensitivity reached an remarkable 1 mutant in over 4 million wild-type molecules [35].

Table 2: Experimentally determined detection limits for dPCR assays

| Target Mutation | Application Context | Lower Limit of Detection (LoD) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR L858R | Non-small cell lung cancer | 1 in 180,000 (0.00056%) to 1 in 4,000,000 | [35] |

| EGFR T790M | Drug resistance in lung cancer | 1 in 13,000 (0.0077%) | [35] |

| Multiple TP53 mutations | Tumor suppressor gene scanning | 0.2% to 1.2% mutation abundance | [37] |

| COLD-ddPCR | Multiple mutation scanning | 0.2% to 1.2% mutation abundance | [37] |

Enhanced Mutation Scanning with COLD-ddPCR

Researchers have combined dPCR with COnvection and Liquid Denaturation PCR (COLD-PCR) to further enhance mutation detection. This hybrid approach enables scanning for unknown mutations within approximately 50-base pair regions of target amplicons. The method uses two differently colored hydrolysis probes (FAM/HEX) both matching the wild-type sequence. The ratio of FAM/HEX-positive droplets remains constant with wild-type templates but deviates when mutations occur under either probe binding site. COLD-PCR cycling conditions enrich mutation-containing sequences, enhancing the ratio change to achieve detection sensitivities between 0.2% to 1.2% mutation abundance for TP53 and EGFR mutations in cell-free DNA [37].

Experimental Protocols: Implementing dPCR for Rare Allele Detection

Core dPCR Workflow Methodology

The fundamental dPCR workflow consists of four key steps, with the partitioning step being crucial for rare allele enrichment:

- Sample Partitioning: The PCR reaction mixture containing the sample DNA is partitioned into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets or microchambers, randomly distributing target molecules according to Poisson distribution.

- Endpoint PCR Amplification: Thermal cycling amplifies target sequences within each partition until completion, without real-time monitoring.

- Fluorescence Detection: Each partition is analyzed for fluorescence signals using specific probes (e.g., FAM, HEX) to determine positive/negative status.

- Absolute Quantification: The fraction of positive partitions is used with Poisson statistics to calculate the absolute concentration of target molecules in the original sample [22] [18].

COLD-Digital PCR Protocol for Mutation Scanning

This advanced protocol combines COLD-PCR with dPCR to detect multiple unknown mutations within a target region:

- Primer and Probe Design: Design two hydrolysis probes (FAM and HEX-labeled) complementary to different segments of the wild-type target sequence within a 50-100 bp region.

- Pre-amplification (Optional): Perform target-specific pre-amplification when analyzing limited samples like cell-free DNA (20 cycles for genomic DNA, 30 cycles for cfDNA) [37].

- Partitioning and COLD-PCR Amplification:

- Partition the sample using droplet or microchamber dPCR systems.

- Implement COLD-PCR cycling conditions: Denature at lower critical temperature (Tc) to preferentially denature and amplify heteroduplex DNA containing mutations, thereby enriching mutation-containing sequences [37].

- Endpoint Fluorescence Detection: Measure fluorescence in both FAM and HEX channels for each partition.

- Ratio Analysis and Mutation Calling:

- Calculate the FAM/HEX fluorescence ratio for each partition.

- Partitions with wild-type sequences will maintain a consistent FAM/HEX ratio.

- Partitions containing mutations under either probe binding site will show deviant ratios.

- Statistical analysis of ratio distributions identifies samples containing mutant alleles [37].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of dPCR for rare allele detection requires specific reagents and systems. The following table details key components and their functions in the experimental workflow.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and systems for dPCR-based rare allele detection

| Reagent/System | Function in Rare Allele Detection | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Partitioning Systems | Creates thousands of individual reactions for single-molecule detection | Droplet generators (Bio-Rad QX200), nanoplate systems (QIAGEN QIAcuity) [18] |

| Hydrolysis Probes | Target-specific detection with fluorescent reporters (FAM, HEX) | TaqMan probes wild-type and mutant-specific [35] |

| Digital PCR Master Mix | Optimized enzyme and buffer system for partitioned amplification | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and stabilizers [35] |

| Reference Standard Sets | Controls for assay validation and sensitivity determination | EGFR Multiplex cfDNA standards with known mutation frequencies [34] |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | DNA treatment for methylation-specific detection | EZ DNA Methylation-Lightning Kit for methylation marker analysis [38] |

Comparative Applications in Clinical Research

Liquid Biopsy and Cancer Monitoring

dPCR's partitioning advantage makes it particularly suited for liquid biopsy applications where ctDNA is extremely scarce. Studies have validated methylation-specific ddPCR assays for lung cancer detection, demonstrating ctDNA-positive rates of 38.7-46.8% in non-metastatic disease and 70.2-83.0% in metastatic cases. The method enabled monitoring of treatment response through longitudinal ctDNA quantification [38].

Alternative Technologies for Rare Variant Detection

While dPCR offers exceptional performance for targeted detection, alternative technologies exist for different application needs:

Next-Generation Sequencing with Molecular Barcodes: This approach tags individual DNA molecules with unique barcodes before amplification and deep sequencing. It enables detection of variants at 0.17% allele frequency while covering multiple genomic regions simultaneously, making it suitable for unknown mutation discovery across larger target areas [34].

BEAMing Technology: Combines emulsion PCR with magnetic beads and flow cytometry to detect rare mutations down to 0.1% variant allele frequency, demonstrating similar sensitivity to dPCR for known mutations [22] [34].

Digital PCR's partitioning methodology provides a fundamental advantage for rare allele detection by physically separating target molecules and enabling absolute quantification at the single-molecule level. Experimental data consistently demonstrates dPCR's ability to detect mutant alleles at frequencies as low as 0.001%, outperforming qPCR particularly for challenging applications like liquid biopsy, rare mutation detection, and analysis of heterogenous samples. While qPCR remains suitable for high-throughput quantification of more abundant targets, dPCR has established itself as the superior technology for detecting low-abundance mutations critical for cancer research, non-invasive prenatal testing, and pathogen detection.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains a cornerstone technology for gene expression analysis and validation of disease biomarkers, particularly when dealing with known targets. For researchers validating a defined genetic signature, the choice of high-throughput platform is critical, balancing factors such as sensitivity, reproducibility, and practical workflow efficiency. This guide objectively compares the performance of established qPCR platforms, focusing on their application in screening workflows. Within the broader context of digital PCR (dPCR) versus quantitative PCR for detecting mutant alleles, understanding these qPCR capabilities is fundamental for selecting the appropriate technology. While dPCR offers superior sensitivity for low-abundance mutations [10], qPCR platforms provide robust, cost-effective solutions for high-throughput expression profiling of known transcripts, making them indispensable for large-scale screening studies and biomarker validation pipelines.

Platform Comparison: Throughput, Sensitivity, and Practical Workflow

Several advanced qPCR platforms have been developed to meet the demands of large-scale studies, each with distinct technical specifications and operational workflows.

Table 1: Comparison of High-Throughput qPCR Platforms for miRNA Validation

| Platform | Reaction Volume | Throughput | Median CV (Precision) | Sensitivity for Low Copy Numbers | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard 96-Well (ViiA7) | 5 μl | 96 wells/run | 0.6% (Range: 0.1-1.9%) | High | Gold standard for sensitivity; low-variability replicates [39] |

| TaqMan Low Density Array (TLDA) | 1 μl | 384 assays/card | 8.3% (Range: 0.3-19.1%) | Moderate | Fixed-panel biomarker validation [39] |

| OpenArray (OA) | 33 nl | 3,072 assays/array | 2.1% (Range: 0.7-4.6%) | High (inverse to volume) | Ultra-high-throughput gene expression [39] |

| Dynamic Array (DA) | 15 nl | 9,216 reactions/chip | 9.5% (Range: 2.2-27.6%) | Variable (platform-dependent) | High-flexibility, custom panel screening [39] |

The data reveal a critical trade-off: platforms with smaller reaction volumes (OpenArray, Dynamic Array) enable massive parallelism but can exhibit higher technical variability, especially for low-abundance targets [39]. The 96-well platform, while lower in throughput, sets the "gold standard" for precision, with a median coefficient of variation (CV) of just 0.6% [39]. CV is a key metric for precision, calculated as the standard deviation divided by the mean quantity of replicates, with lower percentages indicating more consistent results [40].

Performance Metrics: Reproducibility and Detection Fidelity

Beyond basic specifications, performance in detecting real-world biomarker signatures varies significantly across platforms.

Table 2: Performance Metrics in Signature Detection

| Performance Metric | 96-Well (ViiA7) | OpenArray (OA) | Dynamic Array (DA) | Implication for Screening |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fidelity (<1 CT difference) | 99.23% | 88.1% | 77.78% | High fidelity reduces false positives/negatives [39] |

| Fidelity (<2 CT difference) | 99.23% | 96.29% | 91.27% | Critical for reliable fold-change calculations [39] |

| Reproducibility (Run-to-Run) | Highest | Moderate (up to 2.06 CT variation) | Lower (up to 8.17 CT variation) | Impacts longitudinal study reliability [39] |

| Detection of miRNA Signature | Accurate profile | Accurate profile | Skewed profile | Platform choice affects biological conclusions [39] |

The 96-well platform maintained CT variation of less than 1 cycle until the target transcript was expressed at very low levels (CT >30.01), whereas the high-throughput platforms showed substantially increased replicate variability for moderate and low-expression transcripts [39]. This has direct implications for detecting small fold-changes, as excessive variability can reduce a statistical test's ability to discriminate meaningful biological differences [40].

Experimental Protocols for Platform Evaluation and miRNA Signature Validation

Systematic Comparison of qPCR Platforms

The comparative data presented in this guide were derived from a systematic study designed to evaluate platform performance in a real-world research scenario [39].