Ensuring Equity in Early Detection: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Cancer Risk Models Across Diverse Populations

This article addresses the critical challenge of validating cancer risk prediction models across racially, ethnically, and geographically diverse populations—a prerequisite for equitable clinical application.

Ensuring Equity in Early Detection: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Cancer Risk Models Across Diverse Populations

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of validating cancer risk prediction models across racially, ethnically, and geographically diverse populations—a prerequisite for equitable clinical application. We synthesize current evidence on methodologies for external validation, performance assessment across subgroups, and strategies to enhance generalizability. For researchers and drug development professionals, we provide a structured analysis of validation frameworks, comparative model performance metrics including discrimination and calibration, and emerging approaches incorporating AI and longitudinal data. The review highlights persistent gaps in validation for underrepresented groups and rare cancers, offering practical guidance for developing robust, clinically implementable risk stratification tools that perform reliably across all patient demographics.

The Imperative for Inclusive Validation: Why Population Diversity Matters in Cancer Risk Prediction

The Clinical and Ethical Necessity of Broadly Applicable Risk Models

Clinical risk prediction models are fundamental to the modern vision of personalized oncology, providing individualized risk estimates to aid in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection. [1] Their transition from research tools to clinical assets, however, hinges on a single critical property: broad applicability. A model demonstrating perfect discrimination in its development cohort is clinically worthless—and potentially harmful—if it fails to perform accurately in the diverse patient populations encountered in real-world practice. The clinical necessity stems from the imperative to deliver equitable, high-quality care to all patients, regardless of demographic or geographic background. The ethical necessity is rooted in the fundamental principle of justice, requiring that the benefits of technological advancement in cancer care be distributed fairly across society. This guide examines the performance of cancer risk prediction models when validated across diverse populations, comparing methodological approaches and presenting the experimental data that underpin the journey toward truly generalizable models.

Performance Comparison: Single-Cohort vs. Multi-Cohort Validation

The most telling evidence of a model's generalizability comes from rigorous external validation in populations that are distinct from its development cohort. The tables below synthesize quantitative performance data from recent studies to compare model performance in internal versus external settings and across different demographic groups.

Table 1: Comparison of Model Performance in Internal vs. External Validation Cohorts

| Cancer Type | Model Description | Validation Type | Cohort Size (N) | Performance (AUROC) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | Dynamic AI Model (MRS) with prior mammograms | Development (Initial) | Not Specified | 0.81 | [2] |

| External (Province-wide) | 206,929 | 0.78 (0.77-0.80) | [2] | ||

| Pan-Cancer (15 types) | Algorithm with Symptoms & Blood Tests (Model B) | Derivation (QResearch) | 7.46 Million | Not Specified | [3] |

| External (CPRD - 4 UK nations) | 2.74 Million | Any Cancer (Men): 0.876 (0.874-0.878)Any Cancer (Women): 0.844 (0.842-0.847) | [3] | ||

| Cervical Cancer (CIN3+) | LASSO Cox Model (Estonian e-health data) | Internal (10-fold cross-validation) | 517,884 Women | Harrell's C: 0.74 (0.73-0.74) | [4] |

Table 2: Performance Consistency of a Breast Cancer Risk Model Across Racial/Ethnic Groups in an External Validation Cohort (N=206,929) [2]

| Subgroup | Sample Size (with race data) | Number of Incident Cancers | 5-Year AUROC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| East Asian Women | 34,266 | Not Specified | 0.77 (0.75 - 0.79) |

| Indigenous Women | 1,946 | Not Specified | 0.77 (0.71 - 0.83) |

| South Asian Women | 6,116 | Not Specified | 0.75 (0.71 - 0.79) |

| White Women | 66,742 | Not Specified | 0.78 (Overall) |

| All Women (Overall) | 118,093 | 4,168 | 0.78 (0.77 - 0.80) |

The data in Table 1 shows a minor, expected decrease in performance from development to external validation, but the model maintains high discriminatory power, indicating robust generalizability. [3] [2] Table 2 demonstrates that a well-designed model can achieve consistent performance across diverse racial and ethnic groups, a key marker of equitable applicability. [2]

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Large-Scale External Validation of a Multi-Cancer Prediction Algorithm

This protocol, based on the work by Collins et al. (2025), details the validation of a diagnostic prediction algorithm for 15 cancer types across multiple UK nations. [3]

- Aim: To externally validate the performance of two new prediction algorithms (with and without blood tests) for estimating the probability of an undiagnosed cancer.

- Validation Cohorts:

- QResearch Validation Cohort: 2.64 million patients from England.

- CPRD Validation Cohort: 2.74 million patients from Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Using a separate cohort from different countries is a robust test of generalizability.

- Model Inputs: Age, sex, deprivation, smoking, alcohol, family history, medical diagnoses, symptoms (both general and cancer-specific), and commonly used blood tests (full blood count, liver function tests).

- Statistical Analysis:

- Discrimination: Calculated the c-statistic (AUROC) for each of the 15 cancer types separately in men and women. Also used the polytomous discrimination index (PDI) to assess the model's ability to discriminate between all cancer types simultaneously.

- Calibration: Compared predicted versus observed risks to ensure the model was accurately estimating the absolute probability of cancer.

- Subgroup Analysis: Assessed performance by ethnic group, age, and geographical area to evaluate consistency.

- Key Outcome: The models showed high discrimination and calibration in both English and non-English validation cohorts, proving their applicability across a diverse national population. [3]

Protocol 2: Dynamic Risk Prediction Model for Breast Cancer

This protocol, from the study by Kerlikowske et al. (2025), focuses on validating a dynamic AI model that uses longitudinal mammogram data. [2]

- Aim: To validate a dynamic mammogram risk score (MRS) model for predicting 5-year breast cancer risk across a racially and ethnically diverse population in a province-wide screening program.

- Study Design & Cohort: A prognostic study of 206,929 women aged 40-74 from the British Columbia Breast Screening Program (2013-2019), with follow-up through a cancer registry until 2023.

- Model Input: The model's sole input was the four standard views of digital mammograms. Its dynamic nature came from incorporating up to 4 years of prior screening images, in addition to the current mammogram, to capture temporal changes.

- Analysis:

- Discrimination: Primary outcome was the 5-year time-dependent AUROC.

- Calibration: Absolute risk was calibrated to US SEER incidence rates. Calibration plots compared predicted vs. observed 5-year risk.

- Stratified Analysis: Performance was rigorously evaluated across subgroups defined by race and ethnicity (East Asian, Indigenous, South Asian, White), age, breast density, and family history.

- Key Outcome: The dynamic model maintained high and consistent discrimination across all racial and ethnic subgroups, demonstrating that AI-based risk tools can be broadly applicable when properly validated. [2]

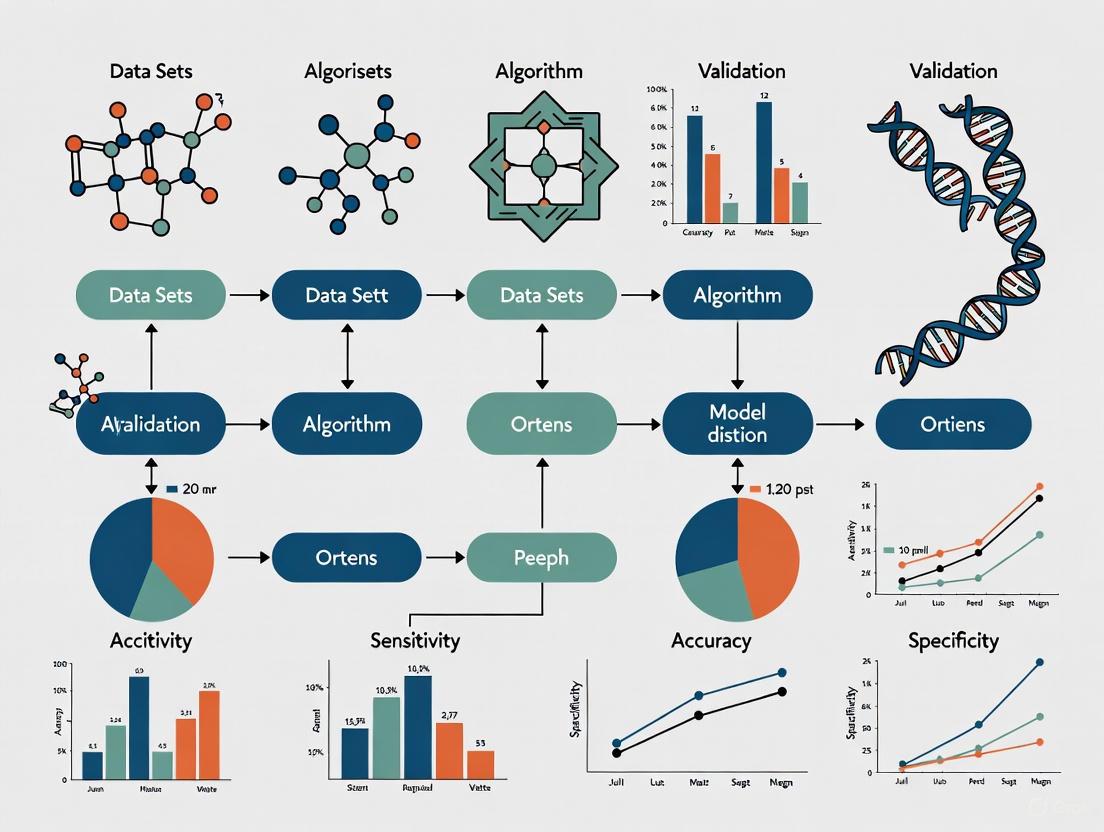

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Dynamic Risk Prediction Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for developing and validating a dynamic risk prediction model, which leverages longitudinal data to update risk estimates over time. [5] [2]

External Validation Pathway for Broad Applicability

This pathway outlines the critical steps for establishing a model's broad applicability through rigorous external validation, a process essential for clinical implementation. [1] [3] [2]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Validation

For researchers developing and validating broadly applicable risk models, the following "toolkit" comprises essential methodological components and resources.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Robust Risk Model Validation

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Technique | Function in Validation | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validation Statistics | C-Statistic (AUROC) | Measures model discrimination: ability to distinguish between cases and non-cases. | [4] [3] [2] |

| Calibration Plots/Slope | Assesses accuracy of absolute risk estimates by comparing predicted vs. observed risks. | [4] [3] | |

| Polytomous Discrimination Index (PDI) | Evaluates a model's ability to discriminate between multiple outcome types (e.g., different cancers). | [3] | |

| Data Resampling Methods | 10-Fold Cross-Validation | Robust internal validation technique for model optimization and error estimation. | [4] |

| Bootstrapping | Generates multiple resampled datasets to obtain confidence intervals for performance metrics. | [2] | |

| Variable Selection | LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) | Regularization technique that performs variable selection to prevent overfitting. | [5] [4] |

| Reporting Guidelines | TRIPOD+AI Checklist | Critical reporting framework to ensure transparent and complete reporting of prediction model studies. | [1] [6] |

| Performance Benchmarking | Net Benefit Analysis (Decision Curve Analysis) | Quantifies the clinical utility of a model by integrating benefits (true positives) and harms (false positives). | [1] |

The journey toward clinically impactful cancer risk prediction models is paved with rigorous, multi-faceted validation. The experimental data and protocols presented herein demonstrate that while performance can generalize well across diverse populations, this outcome is not accidental. It is the product of deliberate methodological choices: the use of large, representative datasets for development; [4] [3] the implementation of dynamic modeling that incorporates longitudinal data; [5] [2] and, most critically, a commitment to comprehensive external validation across geographical, temporal, and demographic domains. [1] [3] [2] The Scientist's Toolkit provides the essential reagents for this task. Ultimately, a model's validity is not proven by its performance on a single, curated cohort, but by its consistent ability to provide accurate, calibrated, and clinically useful risk estimates for every patient it encounters, anywhere. This is the clinical and ethical standard to which the field must aspire.

Cancer risk prediction models are pivotal tools in the era of personalized medicine, enabling the identification of high-risk individuals for targeted screening, early intervention, and tailored preventive strategies [7]. Their development and validation represent an area of "extraordinary opportunity" in cancer research [7]. However, the real-world clinical utility of these models is heavily dependent on two fundamental, and often lacking, properties: their generalizability across diverse populations and their rigorous external validation. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the current performance and development practices of cancer risk prediction models, objectively examining the evidence on their skewed development and the critical gaps in their validation. This analysis is framed for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, with a focus on supporting the broader thesis that advancing cancer care requires a concerted effort to address these shortcomings.

Comparative Performance of Cancer Risk Models

The performance of risk models is primarily quantified by their discrimination (ability to distinguish between those who will and will not develop cancer) and calibration (agreement between predicted and observed risks). The table below summarizes the reported performance of various models, highlighting the diversity in predictive accuracy.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Cancer Risk Prediction Models

| Cancer Type / Focus | Model Name / Type | Population / Cohort | Key Performance Metrics | Key Variables Included |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer [8] | 107 Various Models (Systematic Review) | General & High-Risk Populations | AUC Range: 0.51 - 0.96; O/E Ratio Range: 0.84 - 1.10 (n=8 studies) | Demographic, genetic, and/or imaging-derived variables |

| Breast Cancer [9] | iCARE-Lit (Age <50) | UK-based cohort (White non-Hispanic) | AUC: 65.4; E/O: 0.98 (Well-calibrated) | Classical risk factors (questionnaire-based) |

| Breast Cancer [9] | iCARE-BPC3 (Age ≥50) | UK-based cohort (White non-Hispanic) | AUC: Not Specified; E/O: 1.00 (Well-calibrated) | Classical risk factors (questionnaire-based) |

| Multiple Cancers (Diagnostic) [3] | Model B (With blood tests) | English population (7.46M adults) | Any Cancer C-Statistic: Men: 0.876, Women: 0.844; Improved vs. existing models | Symptoms, medical history, full blood count, liver function tests |

| Cancer Prevention [10] | WCRF/AICR Screener | Spanish PREDIMED-Plus subsample | ICC: 0.68 vs. validated methods; Score range 0-7 | 13 questions on body weight, PA, diet (e.g., red meat, plant-based foods) |

The data reveals a wide spectrum of discriminatory accuracy, particularly in breast cancer, where the Area Under the Curve (AUC) can range from near-random (0.51) to excellent (0.96) [8]. Well-calibrated models, like the iCARE versions, show an Expected-to-Observed (E/O) ratio close to 1.0, indicating high accuracy in absolute risk estimation [9]. Furthermore, the integration of diverse data types, such as blood biomarkers, appears to enhance model performance for diagnostic purposes [3].

Skewed Model Development: Geographic and Cancer-Type Disparities

A critical analysis of the development landscape reveals significant biases that limit the global applicability of cancer risk models.

Table 2: Evidence of Skewed Development in Cancer Risk Prediction Models

| Aspect of Skew | Evidence from Literature | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Geographic Concentration | Of 107 breast cancer models reviewed, 38.3% were developed in the USA and 12% in the UK [8]. Models are often concentrated in the US and UK, with a notable gap for other regions [7]. | Models may not generalize well to populations with different genetic backgrounds, lifestyles, and healthcare environments. |

| Ethnic Homogeneity | Most breast cancer risk models were developed in Caucasian populations [8]. | Predictive performance may degrade in non-Caucasian ethnic groups due to differing risk factor prevalence and effect sizes. |

| Focus on Common Cancers | Significant emphasis on breast and colorectal cancers due to their prevalence [7]. No models were found for several rarer cancers (e.g., brain, Kaposi sarcoma, penile cancer) [7]. | Patients with rarer cancers are deprived of the benefits of risk-stratified prevention and early detection strategies. |

| Variable Integration | Models including both demographic and genetic or imaging data performed better than demographic-only models [8]. | There is a trend towards more complex, multi-factorial models, but these require more data and sophisticated validation. |

This skewed development means that existing models may not perform optimally for populations in Asia, Africa, or South America, or for individuals with rare cancer types, leading to potential misestimation of risk and inequitable healthcare.

Gaps in Model Validation and Proposed Experimental Protocols

A cornerstone of reliable risk prediction is rigorous validation, yet this remains a major gap. External validation—testing a model on data entirely independent from its development set—is infrequently performed.

Detailed Methodology for External Validation

The following workflow, based on established practices from recent high-impact studies [9] [3], outlines a robust protocol for the external validation of a cancer risk prediction model.

The key steps in this validation workflow are:

- Define Validation Objective and Identify Model: Clearly state the purpose (e.g., "to validate the iCARE-BPC3 model for 5-year breast cancer risk in a multi-ethnic European population"). Acquire the complete model specification, including all risk factors, coefficients (log relative risks), and the algorithm for calculating absolute risk [9].

- Secure Independent Validation Cohort(s): Identify one or more cohorts that are entirely separate from the development data. These should represent the target population. For example, the validation of the iCARE models was performed in the UK-based Generations Study, while the development used data from the BPC3 consortium and literature [9]. Sample size must be sufficient, often requiring tens of thousands of participants [8] [3].

- Data Preparation and Harmonization: Extract and harmonize the variables required by the model from the validation cohort. This often requires careful mapping of local data formats and measurements to the model's definitions. Handling missing data (e.g., through statistical imputation) is a critical step [9].

- Calculate Individual Predicted Risks: Apply the model to each individual in the validation cohort to generate a predicted probability of cancer over a specific time horizon (e.g., 5-year risk).

- Assess Model Performance: Evaluate the model using two key metrics:

- Discrimination: Compute the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC). An AUC of 0.5 indicates no discrimination, while 1.0 indicates perfect discrimination. Models with AUC >0.75 are generally considered clinically useful [8] [9].

- Calibration: Compare the predicted number of cancers to the observed number, often summarized as an Expected-to-Observed (E/O) ratio. A ratio of 1.0 indicates perfect calibration. This is also visualized using calibration plots [9].

- Analyze Subgroup Performance: Crucially, assess model performance across key subgroups, such as different ethnicities, age groups, or geographic regions, to identify specific populations for which the model may be poorly calibrated [3].

The Validation Gap in Context

The scale of the validation gap is stark. In a systematic review of 107 breast cancer risk models, only 18 studies (16.8%) reported any external validation [8]. This lack of independent, prospective validation is the single greatest barrier to the broad clinical application of even the most sophisticated models [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Risk Model Research

The development and validation of modern cancer risk models rely on a suite of data, software, and methodological tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cancer Risk Prediction

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| iCARE Software [9] | Software Tool | A flexible platform for building, validating, and applying absolute risk models using data from multiple sources; enables comparative validation studies. |

| PROBAST Tool [8] | Methodological Tool | The "Prediction model Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool" critically appraises the risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies. |

| TRIPOD+AI Checklist [6] | Reporting Guideline | A checklist (Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis + AI) for ensuring complete reporting of prediction model studies. |

| Large EHR Databases (e.g., QResearch, CPRD) [3] | Data Resource | Electronic Health Record databases provide large, longitudinal, real-world datasets ideal for both model development and population-wide external validation. |

| Polygenic Risk Score (PRS) [9] | Genetic Tool | A single score summarizing the combined effect of many genetic variants; its integration can substantially improve risk stratification for certain cancers. |

| WCRF/AICR Screener [10] | Assessment Tool | A validated, short questionnaire to rapidly assess an individual's adherence to cancer prevention guidelines based on diet and lifestyle in clinical settings. |

The current landscape of cancer risk prediction is a tale of promising sophistication hampered by insufficient validation and population-specific development. While models are becoming more powerful by integrating genetic, clinical, and lifestyle data, their real-world utility is confined to populations that mirror their largely Caucasian, Western development cohorts. The path forward requires a paradigm shift where the funding, prioritization, and publication of research are as focused on rigorous, multi-center, multi-ethnic external validation as they are on initial model development. For researchers and drug developers, this means that selecting a risk model for clinical trial recruitment or public health strategy must involve a critical appraisal of its validation status across diverse groups. The future of equitable and effective cancer prevention depends on closing these validation gaps.

Key Populations Requiring Enhanced Representation

The validation of cancer risk prediction models across diverse populations is a critical scientific endeavor, directly impacting the equity and effectiveness of cancer screening and prevention strategies. The underrepresentation of specific racial and ethnic groups in the research used to develop and validate these models threatens their generalizability and can perpetuate health disparities [11]. For instance, African-Caribbean men face prostate cancer rates up to three times higher than their White counterparts, yet the majority of prostate cancer cell lines in research are derived from White men, potentially missing crucial biological variations [11]. This article objectively compares the performance of a contemporary artificial intelligence (AI)-based risk prediction model across well-represented and underrepresented populations, providing supporting experimental data to highlight validation gaps and the urgent need for enhanced representation.

Comparative Performance Analysis of a Dynamic Risk Prediction Model

A 2025 prognostic study externally validated a dynamic AI-based mammogram risk score (MRS) model across a racially and ethnically diverse population within the British Columbia Breast Screening Program [2]. This model innovatively incorporates up to four years of prior screening mammograms, in addition to the current image, to predict the 5-year future risk of breast cancer. The study's findings offer a clear lens through which to analyze model performance across different populations.

The table below summarizes the model's discriminatory performance, measured by the 5-year Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC), across various demographic subgroups [2]. An AUROC of 0.5 indicates performance no better than chance, while 1.0 represents perfect prediction.

Table 1: Discriminatory Performance of the Dynamic MRS Model Across Subgroups

| Population Subgroup | 5-Year AUROC | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Cohort | 0.78 | 0.77 - 0.80 |

| By Race/Ethnicity | ||

| East Asian Women | 0.77 | 0.75 - 0.79 |

| Indigenous Women | 0.77 | 0.71 - 0.83 |

| South Asian Women | 0.75 | 0.71 - 0.79 |

| White Women | 0.78 | 0.77 - 0.80 |

| By Age | ||

| Women Aged ≤50 years | 0.76 | 0.74 - 0.78 |

| Women Aged >50 years | 0.80 | 0.78 - 0.82 |

The data demonstrates that the model maintained robust and consistent discriminatory performance across the racial and ethnic groups studied, with AUROC values showing considerable overlap in their confidence intervals [2]. This is a significant finding, as previous AI models have shown significant performance drops when validated in racially and ethnically diverse populations [2]. Furthermore, the model showed strong performance in younger women (≤50 years), a key population for early intervention.

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for this external validation study, from cohort selection to performance analysis.

Figure 1: Workflow for external validation of the dynamic MRS model.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The validation of the dynamic MRS model followed a rigorous prognostic study design. The cohort was drawn from the British Columbia Breast Screening Program and included 206,929 women aged 40 to 74 years who underwent screening mammography with full-field digital mammography (FFDM) between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2019 [2].

- Data Sources and Linkage: Mammogram images were assembled from multiple fixed-site and mobile screening clinics. This data was prospectively linked to the provincial British Columbia Cancer Registry to identify pathology-confirmed incident breast cancers diagnosed through June 2023, with a maximum follow-up of 10 years [2]. This linkage was performed by staff blinded to mammography features to prevent bias.

- Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria: The study included women with one or more screening mammograms. Those diagnosed with breast cancer within the first six months of cohort entry or with a prior history of breast cancer were excluded to ensure the model was predicting new, future cancer events [2].

- Exposure and Outcome Measures: The primary exposure was the AI-generated MRS, which analyzed the four standard views of digital mammograms. The model dynamically incorporated images from the current screening visit and prior mammograms from up to four years preceding the current visit. The primary outcome was the 5-year risk of breast cancer, with performance assessed via discrimination (AUROC), calibration, and risk stratification [2].

- Statistical Analysis: The performance of several model configurations was examined: age only; the current mammogram only (static MRS); prior mammograms only (dynamic MRS); and combinations of these with age. Stratified sub-analyses were pre-specified for race and ethnicity, age, breast density, and family history. Statistical significance and confidence intervals were estimated using 5000 bootstrap samples, and the reporting adhered to the TRIPOD guideline for prediction models [2].

Populations with Inadequate Representation and the Impact on Research

Despite the successful validation in the British Columbia cohort, significant representation gaps persist in oncology research. The following diagram conceptualizes the cycle of underrepresentation and its consequences for model validity and health equity.

Figure 2: The cycle of underrepresentation and pathways to equitable research.

Key populations consistently identified as requiring enhanced representation include:

- Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic Communities: These groups face a disproportionately higher burden for several cancers but remain inadequately represented in research [11]. For example, the ReIMAGINE Consortium for prostate cancer actively worked to engage diverse communities but found that volunteers from Black, Asian, and minority ethnic backgrounds constituted only 0% to 13% of their meetings, despite the higher risk profile for Black men [11].

- Rare Cancers: A comprehensive analysis of predictive models reveals an uneven distribution of research focus. While breast and colorectal cancers have many models, there are no risk prediction models for several rarer cancers, including brain or nervous system cancer, Kaposi sarcoma, mesothelioma, penile cancer, and anal cancer, among others [7]. This gap is often due to the challenge of gathering sufficient data for model development.

The consequences of these gaps are not merely academic; they directly impact patient care. For instance, a specific gene variation impacting Black men's response to a common prostate cancer drug was missed because the research was conducted predominantly on cell lines from White men [11]. Without comprehensive data from diverse populations, the effectiveness of treatments and the accuracy of risk prediction tools for all populations remain unclear [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

To address the challenge of underrepresentation and conduct equitable cancer risk prediction research, scientists can utilize the following key resources and approaches.

Table 2: Essential Resources for Inclusive Cancer Risk Prediction Research

| Research Reagent or Resource | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Diverse Biobanks & Cohort Data | Provides genomic, imaging, and clinical data from diverse racial, ethnic, and ancestral populations, essential for model development and external validation. Examples include the "All of Us" Research Program and inclusive cancer screening registries. |

| AI-based Mammogram Risk Score (MRS) | An algorithmic tool that analyzes current and prior mammogram images to predict future breast cancer risk. Its function in capturing longitudinal changes in breast tissue has shown robust performance across diverse populations in external validation [2]. |

| ARUARES (The Apricot) Tool | A framework developed by the "Diverse PPI" group to guide researchers on culturally competent practices for engaging diverse communities. It serves as a mental checklist for inclusive research design and participant recruitment at no additional cost [11]. |

| NIHR INCLUDE Ethnicity Framework | A tool designed to help clinical trialists design more inclusive trials by systematically considering factors that may limit participation for underrepresented groups, ensuring research findings are generalizable [11]. |

| Polygenic Risk Scores (PRS) | A statistical construct that aggregates the effects of many genetic variants to quantify an individual's genetic predisposition to a disease. Its accuracy is highly dependent on the diversity of the underlying genome-wide association studies [12]. |

The external validation of the dynamic MRS model demonstrates that achieving consistent performance across racial and ethnic groups is feasible when diverse validation datasets are employed [2]. However, the broader landscape of cancer risk prediction reveals critical gaps in the representation of key populations, including specific racial and ethnic minorities and individuals predisposed to rarer cancers. Addressing these gaps is not merely a matter of equity but a scientific necessity for generating clinically useful and generalizable models. Future efforts must prioritize the intentional inclusion of these populations in all stages of research, from initial model development to external validation, leveraging available tools and frameworks to build a more equitable future for cancer prevention and early detection.

In the field of cancer risk prediction, model validation transcends a simple performance check—it represents a rigorous assessment of a model's readiness for real-world clinical and public health application. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the trifecta of validation metrics—calibration, discrimination, and generalizability—is fundamental to translating predictive algorithms into actionable tools. These metrics respectively answer three critical questions: Are the predicted risks accurate and reliable? Can the model separate high-risk from low-risk individuals? Does the model perform consistently across diverse populations and settings? [13] [14] [15].

The validation process typically progresses through defined stages, starting with internal validation to assess reproducibility and overfitting, followed by external validation to evaluate transportability to new populations [14]. As systematic reviews have revealed, many published prediction models, including hundreds developed for COVID-19, demonstrate significant methodological shortcomings in their evaluation, often emphasizing discrimination while neglecting calibration [14]. This imbalance is problematic because poor calibration can make predictions misleading and potentially harmful for clinical decision-making, even when discrimination appears adequate [15]. For instance, in cancer risk prediction, miscalibration can lead to either false reassurance or unnecessary anxiety and interventions, undermining the model's clinical utility.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of validation methodologies and metrics, anchoring its analysis in the context of cancer risk prediction models. We synthesize current evidence, highlight performance benchmarks across model types, detail experimental protocols for proper evaluation, and visualize key conceptual relationships to equip researchers with the tools necessary for rigorous model assessment.

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Cancer Risk Models

The performance of cancer risk prediction models varies considerably based on their methodology, predictor types, and target population. The table below synthesizes key validation metrics from recent studies to provide a benchmark for model evaluation.

Table 1: Validation Performance of Selected Cancer Risk Prediction Models

| Cancer Type | Model Name | Discrimination (AUC/C-statistic) | Calibration (O/E Ratio) | Key Predictors Included | Population | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | Machine Learning Pooled | 0.74 | N/R | Genetic, Imaging, Clinical | 27 Countries (Systematic Review) | [16] |

| Breast Cancer | Traditional Model Pooled | 0.67 | N/R | Clinical & Demographic | 27 Countries (Systematic Review) | [16] |

| Breast Cancer | Gail (in Chinese cohort) | 0.543 | N/R | Clinical & Demographic | Chinese | [16] |

| Liver Cancer | Fine-Gray Model | 0.782 (5-year risk) | Fine Agreement | Demographics, Lifestyle, Medical History | UK Biobank | [17] |

| Various Cancers | QCancer (Model B) | N/R | Heuristic Shrinkage >0.99 | Symptoms, Medical History, Blood Tests | UK (QResearch/CPRD) | [18] |

Abbreviations: N/R = Not Reported; O/E = Observed-to-Expected.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of female breast cancer incidence models provides a stark comparison between traditional and machine learning (ML) approaches. ML models demonstrated superior discrimination, with a pooled C-statistic of 0.74 compared to 0.67 for traditional models like Gail and Tyrer-Cuzick [16]. Furthermore, the review highlighted a critical issue of generalizability, noting that traditional models such as the Gail model exhibited notably poor predictive accuracy in non-Western populations, with a C-statistic as low as 0.543 in Chinese cohorts [16]. This underscores the necessity of population-specific validation.

Beyond breast cancer, models for other malignancies show promising performance. A liver cancer risk prediction model developed using the UK Biobank cohort achieved an AUC of 0.782 for 5-year risk, demonstrating good discrimination [17]. Its calibration was also reported to show "fine agreement" between observed and predicted risks [17]. Similarly, recent diagnostic cancer prediction algorithms (e.g., QCancer), which include common blood tests, showed excellent internal consistency with heuristic shrinkage factors very close to one (>0.99), indicating no evidence of overfitting—a common threat to model validity [18].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

A robust validation framework requires a structured methodological approach. The following protocols detail the key experiments needed to assess calibration, discrimination, and generalizability.

Protocol for Assessing Model Calibration

Calibration evaluation should be a multi-tiered process, moving from the general to the specific [15].

- Data Preparation: Execute the model to obtain predicted probabilities for each patient in the validation cohort. Ensure the cohort is independent of the development data (external validation) or use appropriate resampling techniques (internal validation) [14].

- Assess Mean Calibration (Calibration-in-the-large):

- Calculate the average predicted risk across all patients in the validation cohort.

- Calculate the overall observed event rate (e.g., cancer incidence).

- Compare the two values. The ratio should be close to 1, indicating that the model does not systematically over- or underestimate risk on average [15].

- Assess Weak Calibration:

- Fit a logistic regression model with the linear predictor from the target model as the only independent variable and the actual outcome as the dependent variable.

- Calibration Intercept (α): A target value of 0 indicates no overall over- or underestimation. A negative value suggests overestimation, a positive value suggests underestimation.

- Calibration Slope (β): A target value of 1 indicates an ideal spread of predictions. A slope < 1 suggests predictions are too extreme (high risks overestimated, low risks underestimated), a slope > 1 suggests predictions are too modest [13] [15].

- Assess Moderate Calibration via Calibration Curves:

- Group patients by their predicted risk (e.g., into deciles or using flexible smoothing).

- For each group, plot the mean predicted risk against the observed event probability.

- A precise calibration curve requires a sufficiently large sample size; a minimum of 200 patients with and 200 without the event has been suggested [15].

- Avoid the Hosmer-Lemeshow Test: This test is not recommended due to its reliance on arbitrary grouping, low statistical power, and uninformative P-value [15].

Protocol for Assessing Model Discrimination

Discrimination evaluates a model's ability to differentiate between patients who do and do not experience the event.

- Calculate the C-statistic (AUC):

- For a binary outcome, this is equivalent to the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve.

- It represents the probability that a randomly selected patient with the event (e.g., cancer) has a higher predicted risk than a randomly selected patient without the event [13] [19].

- Values range from 0.5 (no discrimination) to 1.0 (perfect discrimination).

- Calculate the Discrimination Slope:

- Compute the mean predicted risk in patients who experienced the event.

- Compute the mean predicted risk in patients who did not experience the event.

- The discrimination slope is the difference between these two means. A larger difference indicates better separation between the two groups [13].

Protocol for Assessing Model Generalizability

Generalizability, or transportability, is assessed through external validation.

- Cohort Selection: Validate the model in one or more entirely independent datasets. These should be from different but plausibly related settings (e.g., different geographic regions, healthcare systems, or time periods) [14].

- Performance Comparison: Calculate all relevant calibration and discrimination metrics (as described above) within the external cohort.

- Subgroup Analysis: Stratify the analysis by key demographic or clinical factors (e.g., race/ethnicity, sex, socioeconomic status) to identify performance variations across subpopulations [16] [20].

- Performance Benchmarking: Compare the model's performance in the new setting against existing, alternative models to determine if it offers a tangible improvement [18].

Visualizing the Validation Framework

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and workflow between the core concepts of model validation, highlighting their role in determining clinical utility.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Validation

Successful execution of the validation protocols requires specific statistical tools and methodologies. The table below lists key "research reagents" for a validation scientist.

Table 2: Essential Methodological Reagents for Prediction Model Validation

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Primary Function in Validation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-statistic (AUC) | Discrimination Metric | Quantifies model's ability to rank order risks. | Insensitive to calibration; does not reflect clinical utility [13] [19]. |

| Calibration Slope & Intercept | Calibration Metric | Assesses weak calibration and overfitting. | Slope < 1 indicates overfitting; intercept ≠ 0 indicates overall miscalibration [15]. |

| Calibration Plot | Calibration Visual | Graphical representation of predicted vs. observed risks. | Requires sufficient sample size (>200 events & non-events suggested) [15]. |

| Brier Score | Overall Performance | Measures average squared difference between predicted and actual outcomes. | Incorporates both discrimination and calibration aspects [13]. |

| Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) | Clinical Utility | Evaluates net benefit of using the model for clinical decisions across thresholds. | Superior to classification accuracy as it incorporates clinical consequences [17] [14]. |

| Net Reclassification Improvement (NRI) | Incremental Value | Quantifies improvement in risk reclassification with a new model/marker. | Use is debated; can be misleading without clinical context [13] [14]. |

| Internal Validation (Bootstrapping) | Generalizability Method | Assesses model optimism and overfitting in the derivation data. | Preferred over data splitting as it uses the full dataset [14]. |

The successful validation of a cancer risk prediction model is a multi-faceted endeavor that demands rigorous assessment of calibration, discrimination, and generalizability. As evidenced by comparative studies, models that integrate diverse data types—such as genetic, clinical, and imaging data—often achieve superior performance, yet their applicability can be limited by population-specific factors [16] [21]. The field is moving beyond a narrow focus on discrimination, recognizing that calibration is the Achilles' heel of predictive analytics and that the ultimate test of a model's worth is its clinical utility, often best evaluated through decision-analytic measures like Net Benefit [14] [15]. For researchers and drug developers, adhering to structured experimental protocols and utilizing the appropriate methodological toolkit is paramount for developing predictive models that are not only statistically sound but also clinically meaningful and equitable across diverse populations. Future efforts must focus on robust external validation, model updating, and transparent reporting to bridge the gap between model development and genuine clinical impact.

Validation Frameworks in Action: Statistical Methods and Performance Metrics for Diverse Cohorts

Accurately predicting an individual's risk of developing cancer is a cornerstone of personalized prevention and early detection strategies. For these risk prediction models to be trusted and implemented in clinical practice, they must undergo rigorous validation to ensure their predictions are both accurate and reliable. Validation assesses how well a model performs in new populations, separate from the one in which it was developed, guarding against over-optimistic results. Within this process, three core metrics form the essential toolkit for evaluating predictive performance: the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC), Calibration Plots, and the Expected-to-Observed (E/O) Ratio.

These metrics serve distinct but complementary purposes. Discrimination, measured by AUROC, evaluates a model's ability to separate individuals who develop cancer from those who do not. Calibration, assessed through E/O ratios and calibration plots, determines the accuracy of the absolute risk estimates, checking whether the predicted number of cases matches what is actually observed. Together, they provide a comprehensive picture of model performance that informs researchers and clinicians about a model's strengths, limitations, and suitability for a given population [22] [23]. This guide objectively compares these metrics and illustrates their application through experimental data from recent cancer risk model studies.

The table below defines the three core validation metrics and their roles in model assessment.

Table 1: Core Metrics for Validating Cancer Risk Prediction Models

| Metric | Full Name | Core Question Answered | Interpretation of Ideal Value | Primary Evaluation Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve | How well does the model rank individuals by risk? | 1.0 (Perfect separation) | Model Discrimination |

| Calibration Plot | --- | How well do the predicted probabilities match the observed probabilities? | Points lie on the 45-degree line | Model Calibration |

| E/O Ratio | Expected-to-Observed Ratio | Does the model, on average, over- or under-predict the total number of cases? | 1.0 (Perfect agreement) | Model Calibration |

Experimental Data from Comparative Model Studies

Performance in Breast Cancer Risk Prediction

Independent, comparative studies in large cohorts provide the best evidence for how risk models perform. The following table summarizes results from two such studies that evaluated established breast cancer risk models.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Breast Cancer Risk Prediction Models in Validation Studies

| Study & Population | Model Name | AUROC (95% CI) | E/O Ratio (95% CI) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generations Study [9](Women <50 years) | iCARE-Lit | 65.4 (62.1 to 68.7) | 0.98 (0.87 to 1.11) | Best calibration in younger women. |

| BCRAT (Gail) | 64.0 (60.6 to 67.4) | 0.85 (0.75 to 0.95) | Tendency to underestimate risk. | |

| IBIS (Tyrer-Cuzick) | 64.6 (61.3 to 67.9) | 1.14 (1.01 to 1.29) | Tendency to overestimate risk. | |

| Generations Study [9](Women ≥50 years) | iCARE-BPC3 | Not Reported | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.09) | Best calibration in older women. |

| Mammography Screening Cohort [24](Women 40-84 years) | Gail | 0.64 (0.61 to 0.65) | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.06) | Good calibration and moderate discrimination. |

| Tyrer-Cuzick (v8) | 0.62 (0.60 to 0.64) | 0.84 (0.79 to 0.91) | Underestimation of risk in this cohort. | |

| BCSC | 0.64 (0.62 to 0.66) | 0.97 (0.89 to 1.05) | Good calibration; highest AUC among models with density. |

Performance in Lung Cancer Risk Prediction

Calibration can vary dramatically across different populations, as shown by a large-scale evaluation of lung cancer risk models.

Table 3: Variability in E/O Ratios for Lung Cancer Risk Models Across Cohorts [23]

| Risk Model | Range of E/O Ratios Across 10 European Cohorts | Median E/O Ratio | Notes on Cohort Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bach | 0.41 - 2.51 | >1 | E/O highly dependent on cohort characteristics. |

| PLCOm2012 | 0.52 - 3.32 | >1 | Consistent over-prediction in healthier cohorts. |

| LCRAT | 0.49 - 2.76 | >1 | Under-prediction in high-risk ATBC cohort (male smokers). |

| LCDRAT | 0.51 - 2.69 | >1 | Over-prediction in health-conscious cohorts (e.g., HUNT, EPIC). |

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Protocol for Calculating the E/O Ratio and Assessing Calibration

The E/O ratio is a fundamental measure of overall calibration.

- Step 1: Calculate the Expected Number of Cases (E). For each individual in the validation cohort, use the risk prediction model to compute their probability of developing the cancer within a specified time period (e.g., 5-year risk). Sum these individual probabilities across the entire cohort to obtain the total number of expected cases, E [9] [25].

- Step 2: Determine the Observed Number of Cases (O). Through follow-up of the validation cohort, count the actual number of individuals who developed the cancer within the same time period. This is the observed number of cases, O [9] [25].

- Step 3: Compute the E/O Ratio. The ratio is calculated as E/O. An E/O = 1 indicates perfect overall calibration. An E/O > 1 indicates that the model overestimates risk (predicted more cases than observed), while an E/O < 1 indicates underestimation [9] [23].

- Step 4: Statistical Evaluation. Calculate a 95% confidence interval around the E/O ratio. A ratio is considered statistically significantly different from 1 if its 95% CI does not include 1 [9] [24].

A more nuanced assessment of calibration uses a model-based framework, which can be implemented with statistical software [22]:

- Fit Calibration Models: Fit a regression model in the validation cohort where the outcome is the actual event (cancer) and the predictor is the linear predictor from the risk model (or its log-odds).

Model 1 (Calibration-in-the-large):E(y) = f(ɣ₀ + p), where p is the offset. The intercept ɣ₀ assesses whether predictions are systematically too high or low.Model 2 (Calibration slope):E(y) = f(ɣ₀ + ɣ₁p). The slope ɣ₁ indicates whether the model's discrimination is transportable; an ideal value is 1.

- Create a Calibration Plot: Group individuals by deciles of their predicted risk. For each group, plot the average predicted risk against the observed risk (the proportion who actually developed cancer). A well-calibrated model will have points lying close to the 45-degree line of identity [22].

Figure 1: Workflow for E/O Ratio Calculation and Interpretation

Protocol for Constructing and Interpreting the ROC Curve and AUROC

The ROC curve visualizes the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity across all possible classification thresholds.

- Step 1: Obtain Predictions. For each individual in the validation cohort, obtain the model's predicted probability of having the event (e.g., developing cancer).

- Step 2: Vary the Threshold. Set a series of different probability thresholds (from 0 to 1) at which an individual is classified as "high risk."

- Step 3: Calculate TPR and FPR. For each threshold, calculate the True Positive Rate (TPR/Sensitivity) and False Positive Rate (FPR/1-Specificity) [26].

- TPR = True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives)

- FPR = False Positives / (False Positives + True Negatives)

- Step 4: Plot the ROC Curve. Plot the FPR on the x-axis and the TPR on the y-axis for all thresholds. The resulting curve is the ROC curve [26] [27].

- Step 5: Calculate the AUROC. Calculate the area under the plotted ROC curve. The AUROC can be interpreted as the probability that a randomly selected individual who developed cancer has a higher risk score than a randomly selected individual who did not [26]. The AUROC ranges from 0.5 (no discriminative ability, equivalent to random guessing) to 1.0 (perfect discrimination) [26] [24].

Figure 2: ROC Curve and AUROC Interpretation Guide

Table 4: Key Reagents and Software for Model Validation

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Validation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| iCARE Software [9] | R Software Package | Flexible tool for risk model development, validation, and comparison. | Used to validate and compare iCARE-BPC3 and iCARE-Lit models against established models. |

| PLCOm2012 Model [23] | Risk Prediction Algorithm | Validated model used as a benchmark in comparative lung cancer risk studies. | Served as a comparator in a 10-model evaluation across European cohorts. |

| BayesMendel R Package [24] | R Software Package | Used to run established models like BRCAPRO and the Gail model for risk estimation. | Enabled calculation of 6-year risk estimates in a cohort of 35,921 women. |

| UK Biobank [23] | Epidemiological Cohort Data | Provides large-scale, independent validation data not used in original model development. | Used as a key cohort for externally validating the calibration of lung cancer risk models. |

| TRIPOD Guidelines [25] | Reporting Framework | A checklist to ensure transparent and complete reporting of prediction model studies. | Used in systematic reviews to assess the quality of model development and validation reporting. |

No single metric is sufficient to validate a cancer risk model. AUROC and calibration provide complementary insights, and both must be considered. A model can have excellent discrimination (high AUROC) but poor calibration (E/O ≠ 1), meaning it reliably ranks risks but provides inaccurate absolute risk estimates, which is problematic for clinical decision-making [23]. Conversely, a model can be perfectly calibrated on average (E/O = 1) but have poor discrimination, limiting its utility to distinguish between high- and low-risk individuals [22].

The experimental data reveal critical lessons for researchers. First, even the best models currently show only moderate discrimination, with AUROCs typically in the 0.60-0.65 range for breast cancer [9] [24]. Second, calibration is not an inherent property of the model but a reflection of its match to a specific population. As Table 3 demonstrates, the same lung cancer model can severely overestimate risk in one cohort and underestimate it in another, often due to the "healthy volunteer effect" in epidemiological cohorts [23]. Therefore, external validation in a population representative of the intended clinical use case is mandatory.

Future efforts to improve models involve integrating novel risk factors like polygenic risk scores (PRS) and mammographic density, which are expected to significantly enhance risk stratification [9]. However, these advanced models will require independent prospective validation before broad clinical application. For now, researchers should prioritize model discrimination and careful cutoff selection for screening decisions, while treating calibration metrics as a crucial check on the applicability of a model to their specific target population.

Stratified Analysis Techniques for Racial, Ethnic and Age Subgroups

Validation of cancer risk prediction models across diverse populations is a critical scientific imperative in the quest to achieve health equity in cancer prevention and control. Risk prediction models have the potential to revolutionize precision medicine by identifying individuals most likely to develop cancer, benefit from interventions, or survive their diagnosis [28]. However, their utility depends fundamentally on ensuring validity and reliability across diverse socio-demographic groups [28]. Stratified analysis—the practice of evaluating model performance within specific racial, ethnic, and age subgroups—represents a fundamental methodology for assessing and improving the generalizability of these tools. This comparative guide examines the techniques, findings, and methodological frameworks for conducting stratified analyses of cancer risk prediction models, providing researchers with evidence-based approaches for validating model performance across population subgroups.

The Imperative for Subgroup Analysis in Model Validation

Limitations of Race-Agnostic and Age-Agnostic Models

Cancer risk prediction models developed without consideration of subgroup differences face significant limitations. Models that either erroneously treat race as a biological factor (racial essentialism) or exclude relevant socio-contextual factors risk producing inaccurate estimates for marginalized populations [28]. The origins of these limitations stem from historical precedents, such as the incorporation of "race corrections" that adjust risk estimates based on race without biological justification [28]. These corrections can harm patients by affecting eligibility for services; for instance, race-based adjustments in breast cancer risk models may lower risk estimates for Black women solely based on race, potentially making them ineligible for high-risk screening options [28].

Additionally, the exclusion of socio-contextual factors known to shape health outcomes threatens model validity and perpetuates harm by attributing health disparities to biology rather than structural inequities [28]. Residential segregation, economic disinvestment, environmental toxin exposure, and limited access to health-promoting resources disproportionately affect Black communities and correlate with cancer risk, yet these factors are rarely incorporated into risk models [28].

Dataset Limitations and Representation Gaps

Significant gaps exist in datasets used for model development and validation. Most established cohorts, such as the Nurses' Health Study (approximately 97% White), predominantly represent White populations [28]. While dedicated cohorts like the Black Women's Health Study (N=55,879) and Jackson Heart Study (N=5,301) represent important advances, they remain relatively new and smaller in scale [28]. A 2025 systematic review of breast cancer risk prediction models confirmed that most were developed in Caucasian populations, highlighting ongoing representation issues [8].

Techniques for Stratified Analysis

Statistical Methods for Subgroup Validation

Stratified analysis requires specific statistical techniques to evaluate model performance across subgroups. The following methodologies represent standard approaches for assessing discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility:

Discrimination Analysis: Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) or C-statistic calculated separately for each subgroup measures the model's ability to distinguish between cases and non-cases within that group [29] [8]. AUC values range from 0.5 (no discrimination) to 1.0 (perfect discrimination), with values ≥0.7 generally considered acceptable.

Calibration Assessment: Observed-to-expected (O/E) or expected-to-observed (E/O) ratios evaluate how closely predicted probabilities match observed event rates within subgroups [9] [29]. Well-calibrated models have O/E ratios接近 1.0, with significant deviations indicating poor calibration.

Reclassification Analysis: Examines how risk stratification changes when using new models versus established ones within specific subgroups, assessing potential clinical impact [30].

Net Benefit Evaluation: Quantifies the clinical utility of models using decision curve analysis, balancing true positives against false positives across different risk thresholds [9].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Stratified Model Validation

| Metric | Calculation Method | Interpretation | Application in Subgroup Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (Discrimination) | Area under ROC curve | ≥0.7: Acceptable; ≥0.8: Excellent | Calculate separately for each racial, ethnic, age subgroup |

| O/E Ratio (Calibration) | Observed events ÷ Expected events | 1.0: Perfect calibration; <1.0: Overestimation; >1.0: Underestimation | Compare across subgroups to identify miscalibration patterns |

| Calibration Slope | Slope of observed vs. predicted risks | 1.0: Ideal; <1.0: Overfitting; >1.0: Underfitting | Assess whether risk factors have consistent effects across groups |

| Sensitivity/Specificity | Proportion correctly identified at specific threshold | Threshold-dependent performance | Evaluate clinical utility for screening decisions in each subgroup |

Subgroup-Specific Model Development

When existing models demonstrate poor performance in specific subgroups, researchers may develop subgroup-specific models. The iCARE (Individualized Coherent Absolute Risk Estimation) software provides a flexible framework for building absolute risk models for specific populations by combining information on relative risks, age-specific incidence, and mortality rates from multiple data sources [9]. This approach enables the creation of models that incorporate subgroup-specific incidence rates and risk factor distributions.

Comparative Performance Across Subgroups: Evidence from Multiple Cancers

Breast Cancer Risk Models

A 2021 validation study compared four breast cancer risk prediction models (BCRAT, BCSC, BRCAPRO, and BRCAPRO+BCRAT) across racial subgroups in a diverse cohort of women undergoing screening mammography [29]. The study utilized data from 122,556 women across three large health systems, following participants for five years to assess model performance.

Table 2: Breast Cancer Risk Model Performance by Racial Subgroup

| Model | Overall AUC (95% CI) | White Women AUC | Black Women AUC | Calibration (O/E) Black Women | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCRAT (Gail) | 0.63 (0.61-0.65) | Comparable to overall | Comparable to overall | Well-calibrated | No significant difference in performance between Black and White women |

| BCSC | 0.64 (0.62-0.66) | Comparable to overall | Comparable to overall | Well-calibrated | Incorporation of breast density did not create racial disparities |

| BRCAPRO | 0.63 (0.61-0.65) | Comparable to overall | Comparable to overall | Well-calibrated | Detailed family history performed similarly across groups |

| BRCAPRO+BCRAT | 0.64 (0.62-0.66) | Comparable to overall | Comparable to overall | Well-calibrated | Combined model showed improved calibration in women with family history |

The study found no statistically significant differences in model performance between Black and White women, suggesting that these established models function similarly across racial groups in terms of discrimination and calibration [29]. However, the authors noted limitations in assessing other racial and ethnic groups due to smaller sample sizes.

Beyond racial subgroups, the study also evaluated model performance by age and other characteristics, finding that discrimination was poorer for HER2+ and triple-negative breast cancer subtypes (more common in Black women) and better for women with high BMI [29]. This highlights the importance of considering multiple intersecting characteristics in stratified analysis.

Lung Cancer Risk Models

Research on lung cancer risk prediction models demonstrates how alternative approaches can address screening disparities. The current United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) criteria based solely on age and smoking history have been shown to exacerbate racial disparities [30]. A study of 883 ever-smokers (56.3% African American) evaluated the PLCOm2012 risk prediction model against USPSTF criteria [30].

The PLCOm2012 model significantly increased sensitivity for African American patients compared to USPSTF criteria (71.3% vs. 50.3% at the 1.70% risk threshold, p<0.0001), while showing no significant difference for White patients (66.0% vs. 62.4%, p=0.203) [30]. This demonstrates how risk prediction models can potentially reduce, rather than exacerbate, disparities in cancer screening when properly validated across subgroups.

A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis of lung cancer risk prediction models reinforced these findings, showing that models like LCRAT, Bach, and PLCOm2012 consistently outperformed alternatives, with AUC differences up to 0.050 between models [31]. The review included 15 studies comprising 4,134,648 individuals, providing substantial evidence for model performance across diverse populations.

Age-Based Stratification

Age represents another critical dimension for stratified analysis. Validation of the iCARE breast cancer risk prediction models demonstrated important age-related patterns in performance [9]. In women younger than 50 years, the iCARE-Lit model showed optimal calibration (E/O=0.98, 95% CI=0.87-1.11), while BCRAT tended to underestimate risk (E/O=0.85) and IBIS to overestimate risk (E/O=1.14) in this age group [9]. For women 50 years and older, iCARE-BPC3 demonstrated excellent calibration (E/O=1.00, 95% CI=0.93-1.09) [9].

These findings highlight the necessity of age-stratified validation, as models may perform differently across age groups due to varying risk factor prevalence and incidence rates.

Experimental Protocols for Stratified Validation

Cohort Assembly and Inclusion Criteria

Robust stratified validation requires careful cohort assembly. The breast cancer model validation study by [29] established a protocol that can be adapted for various cancer types:

Multi-site Recruitment: Assemble cohorts from multiple healthcare systems serving diverse populations. The breast cancer study included Massachusetts General Hospital, Newton-Wellesley Hospital, and University of Pennsylvania Health System [29].

Standardized Data Collection: Collect risk factor data through structured questionnaires at the time of screening, including: age, race/ethnicity, age at menarche, age at first birth, BMI, history of breast biopsy, history of atypical hyperplasia, and family history of breast cancer [29].

Electronic Health Record Supplementation: Extract additional data from EHRs, including breast density measurements from radiology reports, pathologic diagnoses, and genetic testing results [29].

Cancer Outcome Ascertainment: Determine cancer cases through linkage with state cancer registries rather than relying solely on institutional data [29].

Follow-up Protocol: Ensure minimum five-year follow-up for all participants to assess near-term risk predictions [29].

Validation Workflow for Stratified Analysis

Statistical Analysis Plan

A comprehensive statistical analysis plan for stratified validation should include:

Pre-specified Subgroups: Define racial, ethnic, and age subgroups prior to analysis, with particular attention to ensuring adequate sample sizes for each group [29].

Handling of Missing Data: Implement standardized approaches for missing risk factor data, such as assuming no atypical hyperplasia for missing values or using multiple imputation where appropriate [29].

Competing Risk Analysis: Account for competing mortality risks using appropriate statistical methods, as implemented in the iCARE framework [9].

Multiple Comparison Adjustment: Apply corrections for multiple testing when evaluating model performance across numerous subgroups.

Sensitivity Analyses: Conduct analyses to test the robustness of findings to different assumptions and missing data approaches.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Stratified Analysis of Cancer Risk Models

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function in Stratified Analysis | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R Statistical Environment with BCRA, BayesMendel, and iCARE packages | Model implementation and validation | Open-source, specialized packages for specific cancer models [29] |

| Risk Model Packages | BCRA R package (v2.1), BayesMendel R package (v2.1-7), BCSC SAS program (v2.0) | Calculation of model-specific risk estimates | Validated algorithms for established models [29] |

| Data Integration Platforms | iCARE (Individualized Coherent Absolute Risk Estimation) Software | Flexible risk model development and validation | Integrates multiple data sources; handles missing risk factors [9] |

| Validation Metrics | PROBAST (Prediction model Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool) | Standardized quality assessment of prediction model studies | Structured evaluation of bias across multiple domains [8] |

| Cohort Resources | Black Women's Health Study, Jackson Heart Study, Multiethnic Cohort Study | Development and validation in underrepresented populations | Focused recruitment of underrepresented groups [28] |

Stratified analysis of cancer risk prediction models across racial, ethnic, and age subgroups represents both an ethical imperative and methodological necessity in advancing precision medicine. The evidence demonstrates that while significant challenges remain in representation and model development, methodologically rigorous subgroup validation can identify performance disparities and guide improvements. The consistent finding that properly validated models can perform similarly across racial groups offers promise for equitable cancer risk assessment.

Future directions should include: (1) development of larger diverse cohorts specifically for model validation; (2) incorporation of social determinants of health as explicit model factors rather than using race as a proxy; (3) standardized reporting of stratified performance in all model validation studies; and (4) investment in resources comparable to genomic initiatives to address social and environmental determinants of cancer risk [28]. Through committed application of stratified analysis techniques, researchers can ensure that advances in cancer risk prediction benefit all populations equally, moving the field toward its goal of eliminating cancer disparities and achieving genuine health equity.

The TRIPOD Guideline for Transparent Reporting of Prediction Models

Transparent and complete reporting is fundamental to the development and validation of clinical prediction models, a process crucial for advancing personalized medicine. The TRIPOD (Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis) guideline provides a foundational checklist to ensure that studies of diagnostic or prognostic prediction models are reported with sufficient detail to be understood, appraised for risk of bias, and replicated [32]. With the increasing use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning in prediction modeling, the original TRIPOD statement has been updated to TRIPOD+AI, which supersedes the 2015 version and provides harmonized guidance for 27 essential reporting items, irrespective of the modeling technique used [33]. This guide compares these reporting frameworks within the critical context of validating cancer risk prediction models across diverse populations.

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of the original TRIPOD statement and its contemporary update, TRIPOD+AI.

| Feature | TRIPOD (2015) | TRIPOD+AI (2024) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Reporting of prediction models developed using traditional regression methods [32]. | Reporting of prediction models using regression or machine learning/AI methods; supersedes TRIPOD 2015 [33]. |

| Number of Items | 22 items [32]. | 27 items [33]. |

| Key Additions in TRIPOD+AI | Not applicable. | New items addressing machine learning-specific aspects, such as model description, code availability, and hyperparameter tuning strategies [33]. |

| Scope of Models Covered | Diagnostic and prognostic prediction models [32]. | Explicitly includes AI-based prediction models, ensuring broad applicability across modern modeling techniques [33]. |

| External Validation Emphasis | Highlights the importance of external validation and its reporting requirements [32]. | Maintains and reinforces the need for transparent reporting of external validation studies, crucial for assessing model generalizability [33]. |

Experimental Validation in Cancer Risk Prediction: A TRIPOD-Compliant Case Study

A 2025 prognostic study validating a dynamic, AI-based breast cancer risk prediction model exemplifies the application of rigorous, transparent research practices in line with TRIPOD principles [2].

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

- Objective: To examine whether a dynamic risk prediction model incorporating prior mammograms could accurately predict future breast cancer risk across a racially and ethnically diverse population in a population-based screening program [2].

- Study Design & Cohort: This prognostic study used data from 206,929 women aged 40–74 years in the British Columbia Breast Screening Program. Participants were screened with full-field digital mammography (FFDM) between 2013 and 2019, with follow-up for incident breast cancers through June 2023 [2].

- Prediction Model & Exposure: The core exposure was an AI-generated mammogram risk score (MRS). The model was "dynamic," meaning it incorporated not just the most current mammogram but also up to four years of prior screening images to capture temporal changes in breast tissue [2].

- Outcomes & Analysis: The primary outcome was the 5-year risk of breast cancer, assessed using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC). Performance was evaluated overall and across subgroups defined by race, ethnicity, and age. Calibration (the agreement between predicted and observed risks) was also assessed [2].

Key Experimental Findings and Performance Data

The study yielded quantitative results that demonstrate the model's performance in a diverse, real-world setting. The data in the table below summarizes the key outcomes.

| Performance Metric | Overall Performance | Performance in Racial/Ethnic Subgroups | Performance by Age |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-Year AUROC (95% CI) | 0.78 (0.77–0.80) [2] | East Asian: 0.77 (0.75–0.79)Indigenous: 0.77 (0.71–0.83)South Asian: 0.75 (0.71–0.79)White: Consistent performance [2] | ≤50 years: 0.76 (0.74–0.78)>50 years: 0.80 (0.78–0.82) [2] |

| Comparative Performance | Incorporating prior images (dynamic MRS) improved prediction compared to using a single mammogram time point (static MRS) [2]. | Performance was consistent across racial and ethnic groups, demonstrating generalizability [2]. | The model showed robust performance across different age groups [2]. |

| Risk Stratification | 9.0% of participants had a 5-year risk >3%; positive predictive value was 4.9% with an incidence of 11.8 per 1000 person-years [2]. | Not specified for individual subgroups. | Not specified for individual age categories. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key resources and methodologies used in the featured breast cancer risk prediction study and the broader field.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Prediction Model Research |

|---|---|

| Full-Field Digital Mammography (FFDM) Images | Served as the primary input data for the AI algorithm. The use of current and prior images enabled the dynamic assessment of breast tissue changes over time [2]. |

| Provincial Cancer Registry (e.g., British Columbia Cancer Registry) | Provided the definitive outcome data (pathology-confirmed incident breast cancers) for model training and validation through record linkage, ensuring accurate endpoint ascertainment [2]. |

| AI-Based Mammogram Risk Score (MRS) Algorithm | The core analytical tool that extracts features from mammograms and computes an individual risk score. The dynamic model leverages longitudinal data for improved accuracy [2]. |

| TRIPOD+AI Checklist | Provides the essential reporting framework to ensure the model's development, validation, and performance are described transparently and completely, facilitating critical appraisal and replication [33]. |

| Color-Blind Friendly Palette (e.g., Wong's palette) | A resource for creating accessible data visualizations, ensuring that charts and graphs conveying model performance are interpretable by all researchers, including those with color vision deficiencies [34]. |

Workflow Diagram for Validating a Cancer Risk Prediction Model

The following diagram, generated with Graphviz, illustrates the logical workflow for the external validation of a cancer risk prediction model across diverse populations, as demonstrated in the case study.

Diagram 1: Validation workflow for a cancer risk prediction model.

The evolution from TRIPOD to TRIPOD+AI represents a critical adaptation to the methodological advances in prediction modeling. For researchers validating cancer risk models across diverse populations, adhering to these reporting guidelines is not merely a matter of publication compliance but a cornerstone of scientific integrity. Transparent reporting, as exemplified by the breast cancer risk study, allows the scientific community to properly assess a model's performance, understand its limitations across different sub-groups, and determine its potential for clinical implementation to achieve equitable healthcare outcomes.

The clinical implementation of artificial intelligence (AI)-based cancer risk prediction models hinges on their generalizability across diverse populations and healthcare settings. A critical step in this process is external validation, where a model's performance is evaluated in a distinct population not used for its development [1]. This case study examines the successful external validation of a dynamic breast cancer risk prediction model within the province-wide, organized British Columbia Breast Screening Program [2]. This validation provides a robust template for assessing model performance across racially and ethnically diverse groups, a known challenge in the field where models developed on homogeneous populations often see performance drops when applied more broadly [2] [7].

The validated model is a dynamic risk prediction tool that leverages AI to analyze serial screening mammograms. Its core innovation lies in incorporating not just a single, current mammogram, but up to four years of prior screening images to forecast a woman's five-year future risk of breast cancer. This approach captures temporal changes in breast parenchyma, such as textural patterns and density, which are significant long-term risk indicators [2].

The primary objective of this external validation study was to determine if the model's performance, previously validated in Black and White women in an opportunistic U.S. screening service, could be generalized to a racially and ethnically diverse population within a Canadian government-organized screening program that operates with biennial digital mammography starting at age 40 [2].

Methodology

Study Population and Data Source

The prognostic study utilized data from the British Columbia Breast Screening Program, drawing from a cohort of 206,929 women aged 40 to 74 who underwent screening mammography between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2019 [2].

- Cohort Characteristics: The cohort had a mean age of 56.1 years and was racially diverse. Among the 118,093 women with self-reported race data, there were 34,266 East Asian, 1,946 Indigenous, 6,116 South Asian, and 66,742 White women [2].