Epigenetic Heterogeneity in Cancer: Decoding Mechanisms, Therapeutic Resistance, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of epigenetic heterogeneity and its pivotal role in cancer development, progression, and therapeutic response.

Epigenetic Heterogeneity in Cancer: Decoding Mechanisms, Therapeutic Resistance, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of epigenetic heterogeneity and its pivotal role in cancer development, progression, and therapeutic response. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental mechanisms driving epigenetic diversity, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA regulation. The content covers advanced methodological approaches for quantifying heterogeneity, examines its contribution to drug resistance and treatment failure, and evaluates emerging epigenetic therapies and biomarker strategies. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge research and clinical applications, this review aims to bridge laboratory findings with therapeutic innovation, offering insights for developing next-generation, personalized cancer treatments that overcome the challenges posed by tumor heterogeneity.

The Landscape of Epigenetic Heterogeneity: Core Mechanisms and Cancer Hallmarks

Epigenetic heterogeneity represents a fundamental layer of variability in cancer biology, encompassing molecular differences that arise without changes to the underlying DNA sequence. This heterogeneity manifests at multiple scales—from individual cells within a single tumor to variations between patients—and significantly influences tumor evolution, therapeutic response, and clinical outcomes. While genetic heterogeneity has been extensively studied, the epigenetic dimension provides crucial insights into phenotypic plasticity, adaptive resistance, and developmental trajectories of malignancies. Epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin remodeling, and non-coding RNA regulation, create a dynamic regulatory framework that interacts with genetic alterations to drive cancer progression [1] [2]. The reversible nature of these modifications distinguishes them from fixed genetic mutations, offering unique challenges and therapeutic opportunities in oncology.

The clinical relevance of epigenetic heterogeneity is increasingly recognized across cancer types. Intratumoral heterogeneity (ITH) creates subclonal populations with diverse therapeutic sensitivities, while interpatient heterogeneity complicates the development of universal treatment strategies. Understanding the scales and mechanisms of epigenetic variation provides a critical foundation for decoding cancer evolution and developing more effective, personalized therapeutic approaches.

Scales and Classifications of Epigenetic Heterogeneity

Intratumoral Heterogeneity (ITH)

Intratumoral epigenetic heterogeneity refers to the diversity of epigenetic states among cancer cells within a single tumor mass. This cellular variability arises through complex stochastic and deterministic processes during tumor evolution. Landmark multi-region sequencing studies have revealed that epigenetic ITH can mirror or even exceed genetic heterogeneity in shaping tumor phenotypes [3] [2]. The TRACERx study on non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) demonstrated that intratumoral methylation distance (ITMD)—a quantitative measure of DNA methylation heterogeneity—correlates significantly with somatic copy number alteration heterogeneity (SCNA-ITH) and intratumoral expression distance (ITED) [4]. This correlation suggests coordinated genomic and epigenomic evolution during tumor development.

Spatial organization of epigenetic states within tumors follows distinct patterns. Heterogeneous methylation patterns are observed not only in malignant cells but also in the tumor microenvironment, where stromal and immune cells exhibit epigenomic alterations influenced by tumor-derived signals [1]. Notably, different genomic regions display varying degrees of epigenetic variability: promoter regions typically show tighter methylation control, while intergenic and enhancer regions exhibit higher methylation heterogeneity, suggesting differential regulatory constraints across the genome [4].

Interpatient Heterogeneity

Interpatient epigenetic heterogeneity encompasses systematic differences in epigenetic landscapes between tumors of the same histological type from different patients. This form of heterogeneity reflects the unique combination of genetic background, environmental exposures, and stochastic events that characterize each individual's cancer. In NSCLC, unsupervised clustering of DNA methylation patterns reliably distinguishes not only between tumor and normal tissue but also between lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) subtypes [4]. These subtype-specific methylation signatures are enriched in distinct biological pathways, suggesting different cells of origin or oncogenic mechanisms.

Interpatient heterogeneity has profound clinical implications, as consistent epigenetic differences between patients with similar cancer types can influence prognosis and treatment response. Methylation profiling reveals that while certain epigenetic alterations are shared across patients (public events), many are private to individual tumors, creating challenges for biomarker development and targeted therapies [4] [2].

Intersection of Genetic and Epigenetic Heterogeneity

The relationship between genetic and epigenetic heterogeneity is complex and bidirectional. Genetic alterations in epigenetic regulators represent a direct link between these layers. Genes encoding "writer," "reader," and "eraser" proteins of epigenetic marks are among the most frequently mutated genes across cancer types [3]. For example, mutations in DNMT3A, TET2, and IDH1/2 can initiate widespread epigenetic dysregulation, creating heterogeneous methylation landscapes [2].

Beyond direct mutations, epigenetic mechanisms can compensate for genetic alterations. In NSCLC, DNA methylation-linked dosage compensation occurs for essential genes co-amplified with neighboring oncogenes, demonstrating how epigenetic programs maintain cellular homeostasis amid genomic instability [4]. This functional interplay suggests that integrated analyses of genetic and epigenetic heterogeneity provide a more complete understanding of tumor evolution than either dimension alone.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Epigenetic Heterogeneity Scales

| Feature | Intratumoral Heterogeneity | Interpatient Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Variation among cancer cells within a single tumor | Variation between tumors of same type in different patients |

| Primary drivers | Clonal evolution, microenvironmental niches, stochastic epigenetic drift | Germline genetics, environmental exposures, different cells of origin |

| Technical challenges | Sampling bias, cellular admixture, spatial resolution | Cohort effects, normalization across samples, confounding variables |

| Clinical impact | Therapeutic resistance, tumor adaptation, relapse | Differential treatment response, prognostic stratification |

| Representative metrics | Intratumoral methylation distance (ITMD) [4] | Methylation subtype classification, epigenetic signatures [4] |

Molecular Mechanisms Driving Epigenetic Heterogeneity

DNA Methylation Heterogeneity

DNA methylation heterogeneity represents the most extensively characterized form of epigenetic variation in cancer. This heterogeneity manifests as variable 5-methylcytosine (5mC) patterns across tumor cells, influencing transcriptional programs and cellular phenotypes. The development of quantitative measures like intratumoral methylation distance (ITMD) has enabled systematic assessment of methylation heterogeneity and its relationship to other molecular and clinical features [4]. Methylation heterogeneity arises through several interconnected mechanisms:

- Stochastic methylation errors: The fidelity of DNA methylation maintenance during cell division is imperfect, leading to random methylation changes that accumulate over successive generations. This process functions as a "molecular clock" recording mitotic history [3].

- Regulatory compartmentalization: Genomic regions differ in their susceptibility to methylation changes. CpG islands in promoter regions are generally protected from methylation, while CpG island shores and enhancer elements display more dynamic methylation patterns [4].

- Environmental influences: Regional variations in oxygenation, nutrient availability, and stromal interactions within tumors create distinct microenvironmental niches that shape methylation patterns through cellular stress responses [5].

Methylation heterogeneity has functional consequences beyond transcriptional regulation. In NSCLC, parallel convergent evolution events involving both copy number loss and promoter hypermethylation affect tumor suppressor genes, with LUSC tumors showing greater interplay between these mechanisms than LUAD [4]. This suggests that methylation heterogeneity can provide alternative pathways to oncogenic states.

Histone Modification and Chromatin Organization

Histone modification heterogeneity contributes significantly to phenotypic diversity in cancer through several mechanisms. Post-translational modifications of histone tails—including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and newer modifications like crotonylation and succinylation—create a complex combinatorial code that influences chromatin accessibility and transcriptional states [6] [1]. The emergence of novel histone modifications continues to expand the potential dimensions of epigenetic heterogeneity.

Histone fold domain mutations represent an emerging mechanism of epigenetic heterogeneity. Approximately 7% of cancer patients harbor mutations in histone fold domains, with H2B E76K being the most common. This mutation destabilizes the H2B/H4 interface, leading to increased chromatin accessibility at polycomb-repressed regions and upregulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition pathways [7]. Such structural alterations in nucleosome organization create lasting epigenetic and transcriptional heterogeneity.

Chromatin remodeling complexes further contribute to epigenetic heterogeneity by dynamically repositioning nucleosomes and altering chromatin accessibility. The SWItch/Sucrose NonFermentable (SWI/SNF) complex, frequently mutated in cancer, functions as a chromatin remodeler that orchestrates coordinated differentiation of multiple cell lineages during development and tumor evolution [8]. The composition and activity of these complexes vary among cancer cells, generating heterogeneous chromatin landscapes.

Higher-Order Chromatin Architecture

Three-dimensional genome organization represents an emerging dimension of epigenetic heterogeneity. Spatial chromatin architecture, organized by CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) and cohesion complexes, creates topologically associated domains (TADs) that constrain regulatory interactions [7]. Mutations in persistent CTCF binding sites, which occur with higher frequency in cancers such as prostate and breast cancer, disrupt higher-order chromatin architecture and gene regulation programs. These structural variations in chromatin folding create heterogeneity in enhancer-promoter interactions and transcriptional outputs across cell populations within tumors.

Diagram 1: Mechanisms Generating Chromatin Architecture Heterogeneity. Mutations in structural chromatin components disrupt higher-order organization, leading to heterogeneous gene expression patterns and cellular states.

Non-Coding RNA Regulation

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) constitute a diverse class of regulatory molecules that contribute significantly to epigenetic heterogeneity. These RNA species—including microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs)—orchestrate complex regulatory networks that influence chromatin states and gene expression programs [6] [1]. The heterogeneous expression of ncRNAs across tumor cells creates variation in regulatory outcomes, potentially driving phenotypic diversity.

ncRNAs contribute to epigenetic heterogeneity through several mechanisms. miRNAs can target epigenetic regulators such as DNMT3A/3B, as demonstrated by miR-29b-mediated regulation during zygotic genome activation, which helps maintain proper DNA demethylation patterns [8]. lncRNAs can recruit chromatin-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci, creating localized epigenetic states that vary across cell populations. The spatial and temporal heterogeneity of ncRNA expression thus translates into diverse epigenetic and transcriptional outcomes within tumors.

Quantitative Assessment of Epigenetic Heterogeneity

Methodological Frameworks

Quantifying epigenetic heterogeneity requires specialized experimental and computational approaches that capture variation at appropriate resolution scales. Bulk sequencing methods provide population-averaged signals but obscure single-cell heterogeneity, while single-cell technologies enable resolution of cellular diversity but with higher noise and cost [3]. Key methodological considerations include:

- Deconvolution of cellular mixtures: Computational approaches like Copy number-Aware Methylation Deconvolution Analysis of Cancers (CAMDAC) model pure tumor methylation rates by accounting for normal contamination and copy number variations, enabling more accurate assessment of methylation heterogeneity [4].

- Single-cell epigenomic profiling: Emerging technologies for single-cell DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility, and histone modification analysis directly measure epigenetic heterogeneity at cellular resolution, revealing cell-to-cell variation patterns.

- Spatial epigenomics: Integrating spatial coordinates with epigenetic measurements preserves architectural context, enabling assessment of geographical heterogeneity patterns within tumor tissue [7].

The development of epigenetic clocks—machine learning algorithms that estimate biological age from DNA methylation patterns—represents another quantitative framework with relevance to cancer heterogeneity. These clocks capture systematic methylation changes associated with cellular aging, which may be perturbed in tumor evolution [7].

Key Metrics and Analytical Tools

Several quantitative metrics have been developed specifically to measure epigenetic heterogeneity:

- Intratumoral Methylation Distance (ITMD): A pairwise distance metric based on Pearson correlation between methylation rates across all CpGs in different tumor regions. ITMD quantifies methylation heterogeneity within and between tumors and correlates with SCNA heterogeneity and transcriptional variation [4].

- Methylation Rate Ratio (MR/MN): Classifies genes based on the rate of hypermethylation at regulatory versus nonregulatory CpGs to identify driver genes exhibiting recurrent functional hypermethylation [4].

- Epigenetic Regulatory Network (ERN) Analysis: Conceptualizes the collection of complex epigenetic modifications that drive cellular states as an integrated network. This framework helps identify "epigenetic fragility" points where functional redundancy is lost in cancer cells [7].

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Epigenetic Heterogeneity Assessment

| Metric | Description | Application | Technical Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intratumoral Methylation Distance (ITMD) | Pairwise Pearson distance between methylation rates across tumor regions | Quantifies methylation heterogeneity and correlates with genetic and transcriptomic heterogeneity [4] | Multi-region sampling, bisulfite sequencing, CAMDAC deconvolution |

| MR/MN Classification | Ratio of hypermethylation rates at regulatory vs. nonregulatory CpGs | Identifies genes under positive selection for promoter hypermethylation [4] | RRBS or whole-genome bisulfite sequencing, annotation of regulatory regions |

| Epigenetic Clock Algorithms | Multivariate predictors of biological age from methylation patterns | Assesses epigenetic age acceleration and its heterogeneity within tumors [7] | Array-based or sequencing methylation data, reference datasets |

| Allelic Methylation Heterogeneity | Measurement of methylation pattern diversity at individual molecules | Reconstructs lineage relationships and mitotic history [3] | Single-molecule or single-cell methylation protocols |

Experimental Approaches and Research Reagents

Core Methodologies for Epigenetic Heterogeneity Research

Investigating epigenetic heterogeneity requires specialized experimental approaches designed to capture variation at appropriate biological scales. The selection of methodology depends on the specific epigenetic layer under investigation, desired resolution, and analytical objectives.

Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) provides a cost-effective approach for DNA methylation analysis at CpG-rich regions, enabling profiling of multiple tumor regions to assess methylation heterogeneity. The TRACERx study applied RRBS to 217 tumor regions from 59 NSCLC patients, followed by CAMDAC deconvolution to obtain cancer cell-specific methylation rates free from normal cell contamination and copy number confounding [4]. This approach enabled identification of heterogeneous methylation patterns and their relationship to genomic alterations.

Single-cell methylome analysis technologies represent the frontier for resolving epigenetic heterogeneity. These methods include single-cell bisulfite sequencing, single-cell combinatorial indexing for methylation analysis, and emerging techniques that couple methylation profiling with other molecular modalities. While technically challenging, these approaches directly measure cell-to-cell variation without inferring heterogeneity from bulk measurements [3].

Epigenome editing tools enable causal investigation of specific epigenetic alterations. CRISPR-dCas9 systems fused to epigenetic modifiers (methyltransferases, demethylases, acetyltransferases) allow targeted manipulation of epigenetic states at specific loci. In colorectal cancer metastasis research, this approach has been used to functionally validate DNA methylation changes at key regulatory loci [7].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Epigenetic Heterogeneity Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Tools | Application in Heterogeneity Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS), Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS), ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq | Genome-wide mapping of DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility, and histone modifications across multiple tumor regions [4] |

| Epigenome Editing | CRISPR-dCas9-DNMT3A, CRISPR-dCas9-TET1, CRISPR-dCas9-HDAC | Functional validation of heterogeneous epigenetic alterations by targeted writing/erasing of specific marks [7] |

| Single-Cell Analysis | 10x Genomics Single Cell Multiome, scNMT-seq (single-cell nucleosome, methylation, and transcription) | Resolution of cell-to-cell variation in epigenetic states and correlation with transcriptomic heterogeneity [3] |

| Computational Tools | CAMDAC, Seurat, Monocle, DNA methylation clock algorithms | Deconvolution of bulk data, single-cell analysis, trajectory inference, and epigenetic age estimation [4] [7] |

| Chemical Inhibitors | 5-azacytidine (DNMT inhibitor), Vorinostat (HDAC inhibitor), Ouabain (LEO1 inhibitor) | Perturbation of epigenetic regulation to assess functional consequences and therapeutic potential [8] [7] |

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Epigenetic Heterogeneity Research. Integrated approaches combining multi-region sampling with diverse profiling methods and computational analyses enable comprehensive characterization of epigenetic heterogeneity.

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Opportunities

Diagnostic and Prognostic Applications

Epigenetic heterogeneity has significant implications for cancer diagnosis, classification, and prognosis. The degree of intratumoral epigenetic heterogeneity may itself serve as a prognostic marker, with more heterogeneous tumors often exhibiting enhanced adaptive capacity and worse clinical outcomes [3]. In NSCLC, the extent of methylation heterogeneity correlates with copy number and transcriptomic heterogeneity, suggesting it captures fundamental aspects of tumor evolution [4].

DNA methylation biomarkers show particular promise for cancer detection and classification. Methylation patterns can distinguish histological subtypes, as demonstrated by the clear separation of LUAD and LUSC in methylation-based clustering [4]. Emerging applications include liquid biopsy approaches that detect tumor-derived DNA methylation patterns in circulating cell-free DNA, potentially enabling non-invasive assessment of tumor heterogeneity and monitoring of clonal dynamics during treatment [7].

Therapeutic Resistance and Epigenetic Plasticity

Therapeutic resistance represents the most direct clinical consequence of epigenetic heterogeneity. Diverse epigenetic states within tumors create pre-existing populations with varying susceptibility to therapeutic agents. Rare subpopulations with specific epigenetic configurations can survive treatment and initiate relapse, a phenomenon observed in multiple cancer types [6] [3]. This form of non-genetic resistance is particularly challenging because it can emerge rapidly through epigenetic plasticity without requiring new mutations.

The reversible nature of epigenetic modifications creates opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Epigenetic therapies targeting DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), histone deacetylases (HDACs), and other epigenetic modifiers may alter cellular states and sensitize resistant populations to conventional treatments [8] [6]. However, the effectiveness of these approaches depends on understanding and addressing the underlying heterogeneity of epigenetic states.

Epigenetic Therapy and Combination Strategies

Epigenetic-targeted drugs represent a growing class of therapeutic agents with potential to modulate tumor heterogeneity. Approved agents include DNMT inhibitors (azacitidine, decitabine), HDAC inhibitors (vorinostat, romidepsin), and EZH2 inhibitors (tazemetostat), with numerous others in clinical development [8]. These agents aim to reverse aberrant epigenetic states associated with tumorigenesis, but their efficacy as monotherapies has been limited, particularly in solid tumors.

Combination strategies that integrate epigenetic therapies with other treatment modalities show promise for overcoming resistance rooted in epigenetic heterogeneity. Potential synergistic combinations include:

- Epigenetic therapy + immunotherapy: DNMT and HDAC inhibitors can enhance tumor immunogenicity by increasing antigen presentation and activating endogenous retroviruses, potentially improving response to immune checkpoint inhibitors [6].

- Epigenetic therapy + targeted therapy: Simultaneous targeting of epigenetic regulators and specific oncogenic signaling pathways may prevent escape mechanisms and enhance efficacy.

- Epigenetic therapy + chemotherapy: Priming tumors with epigenetic modulators can sensitize previously resistant populations to conventional cytotoxic agents.

The timing and sequencing of combination therapies present critical considerations, as epigenetic reprogramming may require time to alter cellular states before subsequent treatments become effective. Additionally, the dynamic nature of epigenetic heterogeneity necessitates monitoring approaches to track clonal evolution during treatment.

Epigenetic heterogeneity represents a fundamental property of cancer that intersects with genetic variation to drive tumor evolution and therapeutic resistance. The multidimensional nature of epigenetic regulation—spanning DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin architecture, and non-coding RNA networks—creates numerous layers of potential heterogeneity that influence cellular phenotypes and clinical behavior. Understanding these complex dynamics requires integrated approaches that capture variation across spatial scales, temporal transitions, and molecular modalities.

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas. Single-cell multi-omics technologies that simultaneously measure multiple epigenetic layers with genomic and transcriptomic information will provide unprecedented resolution of cellular states and their relationships. Spatial epigenomics approaches will contextualize heterogeneity within tissue architecture, revealing geographical patterns of epigenetic variation. Functional dissection of heterogeneous epigenetic states through CRISPR-based screening and epigenome editing will establish causal relationships between specific epigenetic alterations and phenotypic outcomes.

From a clinical perspective, addressing epigenetic heterogeneity presents both challenges and opportunities. While heterogeneity complicates treatment by creating diverse cell populations with varying drug sensitivities, the reversible nature of epigenetic states offers therapeutic avenues for reprogramming resistant cells into sensitive states. The ongoing development of epigenetic therapies, particularly in rational combination regimens, holds promise for overcoming resistance and improving patient outcomes across diverse cancer types.

Ultimately, advancing our understanding of epigenetic heterogeneity will require continued methodological innovation, computational development, and integration across biological scales. As these efforts progress, they will progressively refine cancer classification, prognostication, and therapeutic strategies, moving toward more effective personalized approaches that account for the complex epigenetic landscapes of individual tumors.

Epigenetic regulation, comprising heritable changes in gene expression that do not alter the underlying DNA sequence, has emerged as a fundamental contributor to cancer initiation and progression. The principal mechanisms of DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling collectively establish a complex regulatory layer that controls genome accessibility and function [9]. In cancer, the precise patterns governed by these mechanisms become dysregulated, leading to epigenetic heterogeneity that drives tumor evolution, therapeutic resistance, and metastatic behavior [9] [10]. This technical review examines the core epigenetic mechanisms, their interrelationships, and their collective impact on creating the cellular diversity characteristic of malignant disease.

The reversibility of epigenetic modifications presents unique therapeutic opportunities not available with genetic mutations [9]. Unlike permanent genetic alterations, the dynamic nature of the epigenome allows for pharmacological intervention to reverse aberrant gene expression patterns, making epigenetic proteins attractive targets for drug development [9] [10]. Understanding the molecular principles governing these mechanisms is therefore critical for developing novel cancer therapeutics and biomarkers for patient stratification.

DNA Methylation in Cancer

Molecular Mechanisms and Enzymatic Machinery

DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the carbon-5 position of cytosine bases, primarily within cytosine-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, forming 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) [9]. This modification is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), which utilize S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as the methyl donor [9]. The DNMT family includes DNMT1, responsible for maintaining methylation patterns during DNA replication, and DNMT3A and DNMT3B, which establish new methylation patterns de novo [9].

Active DNA demethylation is facilitated by ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes, which catalyze the oxidation of 5-mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC) and further oxidized derivatives [9]. This initiates a demethylation pathway that can eventually restore an unmethylated cytosine, providing dynamic regulation of the DNA methylome [9].

Table 1: Key Enzymatic Regulators of DNA Methylation

| Enzyme Category | Representative Members | Primary Function in DNA Methylation |

|---|---|---|

| De novo Methyltransferases | DNMT3A, DNMT3B | Establish initial DNA methylation patterns during development |

| Maintenance Methyltransferase | DNMT1 | Copies existing methylation patterns to daughter strands during DNA replication |

| Demethylases | TET1, TET2, TET3 | Initiate DNA demethylation by oxidizing 5-mC to 5-hmC and other derivatives |

Dysregulation in Cancer and Super-Enhancer Methylation

Cancer cells exhibit characteristic DNA methylation abnormalities, including genome-wide hypomethylation that promotes genomic instability, and site-specific hypermethylation at promoter regions of tumor suppressor genes that leads to their transcriptional silencing [9]. This paradoxical pattern represents a fundamental epigenetic hallmark of cancer.

Recent research has highlighted the significance of DNA methylation alterations at super-enhancers - specialized regulatory regions characterized by dense clustering of transcription factors and coactivators that drive high-level expression of genes controlling cell identity [11]. In cancer, super-enhancers controlling oncogenic drivers often display abnormal DNA methylation patterns [11]. Hypomethylation at these sites frequently accompanies oncogene hyperactivation, while hypermethylation can repress tumor suppressor mechanisms [11].

The relationship between DNA methylation and super-enhancer activity demonstrates considerable variability, even within the same genomic region across different cell states [11]. This methylation plasticity at regulatory elements represents an important mechanism for generating epigenetic heterogeneity within tumors.

Experimental Analysis of DNA Methylation

Bisulfite Sequencing Methods: Treatment of DNA with bisulfite converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils (detected as thymines in sequencing), while methylated cytosines remain protected. This chemical modification enables single-base resolution mapping of methylation states across the genome [11]. Variations include whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) for comprehensive coverage and reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) for cost-effective analysis of CpG-rich regions.

Methylation-Sensitive Restriction Enzymes: These enzymes differentially cleave DNA based on methylation status, allowing for targeted assessment of specific loci.

Array-Based Platforms: Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip arrays provide cost-effective profiling of over 850,000 CpG sites, covering promoter regions, gene bodies, and enhancer elements.

Histone Modifications

Complexity of the Histone Code

Histones are subject to a wide array of post-translational modifications that collectively form a "histone code" that regulates chromatin structure and function [12]. These modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation, ADP-ribosylation, lactylation, and crotonylation [12]. The combinatorial nature of these marks creates a sophisticated regulatory system that influences DNA accessibility, transcription, replication, and repair.

The enzymes responsible for histone modifications fall into three functional categories: "writers" that add modifications, "erasers" that remove them, and "readers" that recognize specific marks and recruit effector proteins [9]. This dynamic system allows for rapid changes in chromatin state in response to cellular signals.

Table 2: Major Histone Modifications and Their Functional Roles

| Modification Type | Common Sites | General Function | Associated Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylation | H3K9, H3K14, H3K27, H4K5, H4K8, H4K12, H4K16 | Chromatin relaxation, transcriptional activation | HATs, HDACs |

| Methylation | H3K4, H3K9, H3K27, H3K36, H3K79, H4K20 | Context-dependent; can activate or repress transcription | HMTs, KDMs |

| Phosphorylation | H3S10, H3S28 | Chromatin condensation, cell division, signaling response | Kinases, Phosphatases |

| Lactylation | H3K9, H3K14, H3K18, H3K23, H3K27, H3K56 | Links metabolism to gene regulation; promotes tumor progression | - |

Histone Modifications in the Tumor Microenvironment

Histone modifications play a crucial role in shaping the tumor microenvironment (TME), particularly through their regulation of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [12]. TAMs exhibit remarkable plasticity, polarizing into either pro-inflammatory M1 phenotypes that inhibit tumor growth or immunosuppressive M2 phenotypes that promote tumor progression [12]. Specific histone modifications regulate this polarization process, influencing the expression of genes that determine macrophage function.

For example, histone lactylation has emerged as a mechanism that links cellular metabolism to epigenetic regulation in the TME [12]. Lactate produced by tumor cells through aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) can drive histone lactylation, influencing gene expression patterns that support tumor progression [12]. This represents a direct connection between metabolic reprogramming in cancer and epigenetic changes in the TME.

Experimental Analysis of Histone Modifications

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq): This method uses antibodies specific to histone modifications to immunoprecipitate cross-linked protein-DNA complexes, followed by high-throughput sequencing to map modification patterns genome-wide [11]. Key steps include:

- Cross-linking proteins to DNA with formaldehyde

- Chromatin fragmentation by sonication or enzymatic digestion

- Immunoprecipitation with modification-specific antibodies

- Reversal of cross-links and library preparation

- High-throughput sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics: Enables comprehensive identification and quantification of histone modifications without antibody requirements.

Immunofluorescence and Immunohistochemistry: Allow spatial visualization of histone modifications in tissue context.

Chromatin Remodeling

Mechanisms of Nucleosome Repositioning

Chromatin remodeling involves the ATP-dependent repositioning or restructuring of nucleosomes to regulate DNA accessibility [13]. This process is catalyzed by multi-subunit complexes that utilize the energy from ATP hydrolysis to slide, evict, or restructure nucleosomes [13]. The human genome encodes several families of chromatin remodeling complexes, including SWI/SNF, ISWI, CHD, and INO80 families.

Recent structural studies using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) have provided unprecedented insights into the mechanism of nucleosome sliding [13]. Researchers captured 13 distinct structures of the remodeling enzyme SNF2H interacting with nucleosomes in the presence of ATP, revealing intermediate states along the nucleosome sliding pathway [13]. This continuous motion illustrates how remodelers translocate DNA along the nucleosome surface to control access to genetic information.

Chromatin Architecture in Cancer Prognosis

Three-dimensional chromatin organization plays a critical role in maintaining proper gene expression patterns, and its disruption is increasingly recognized as a hallmark of cancer [14]. Recent research in prostate cancer has revealed that the degree of chromatin decompartmentalization can stratify patients into distinct molecular subtypes with different clinical outcomes [14].

Studies have identified two principal subgroups: one with a Low Degree of Decompartmentalization (LDD) and another with a High Degree of Decompartmentalization (HDD) [14]. Counterintuitively, the HDD subgroup exhibits extensive chromatin reorganization associated with diminished oncogenic potential, showing repression of molecular pathways involved in extracellular matrix remodeling and cellular plasticity [14]. From this distinction, researchers derived an 18-gene transcriptional signature capable of differentiating HDD from LDD cases, demonstrating prognostic relevance across multiple independent cohorts totaling over 900 patients [14].

Experimental Analysis of Chromatin Remodeling

4f-SAMMY-seq: This method sequentially isolates distinct chromatin fractions based on accessibility and solubility properties, which correlate with epigenetic and transcriptional status [14]. The technique involves:

- Enzymatic digestion of fresh tissue samples to obtain cell suspensions

- Sequential fractionation to separate chromatin by solubility

- High-throughput sequencing of individual fractions

- Analysis of solubility profiles as ratios of sequencing reads between fractions

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with Sequencing (ATAC-seq): Maps genome-wide chromatin accessibility using a hyperactive Tn5 transposase.

Chromosome Conformation Capture (3C-based methods): Analyze three-dimensional genome architecture through proximity ligation.

Interplay of Epigenetic Mechanisms in Cancer

Integrated Epigenetic Regulation

The three principal epigenetic mechanisms do not function in isolation but rather form an integrated regulatory network. DNA methylation and histone modifications frequently exhibit crosstalk, with each influencing the establishment and maintenance of the other [9]. For example, methylation of DNA CpG islands often occurs in conjunction with specific histone modifications, particularly H3K9 methylation and histone deacetylation, to reinforce transcriptional repression [9].

Chromatin remodeling complexes interpret histone modifications through specialized domains that recognize specific marks, thereby coupling the energy-dependent restructuring of nucleosomes with the chemical information encoded in histone tails [13]. This coordinated action ensures precise spatial and temporal control of genome function.

Epigenetic Heterogeneity and Therapeutic Implications

The dynamic nature of epigenetic regulation contributes significantly to tumor heterogeneity, both between different patients (inter-tumor heterogeneity) and within individual tumors (intra-tumor heterogeneity) [9] [10]. This heterogeneity poses a major challenge for cancer therapy, as subpopulations of cells with distinct epigenetic states may exhibit different sensitivities to treatment.

The reversible nature of epigenetic modifications has spurred the development of epigenetic therapies targeting DNA methyltransferases, histone deacetylases, and other epigenetic regulators [9] [15]. Combination approaches that target multiple epigenetic mechanisms simultaneously or pair epigenetic drugs with conventional chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or immunotherapy represent promising strategies to overcome therapeutic resistance rooted in epigenetic heterogeneity [15] [10].

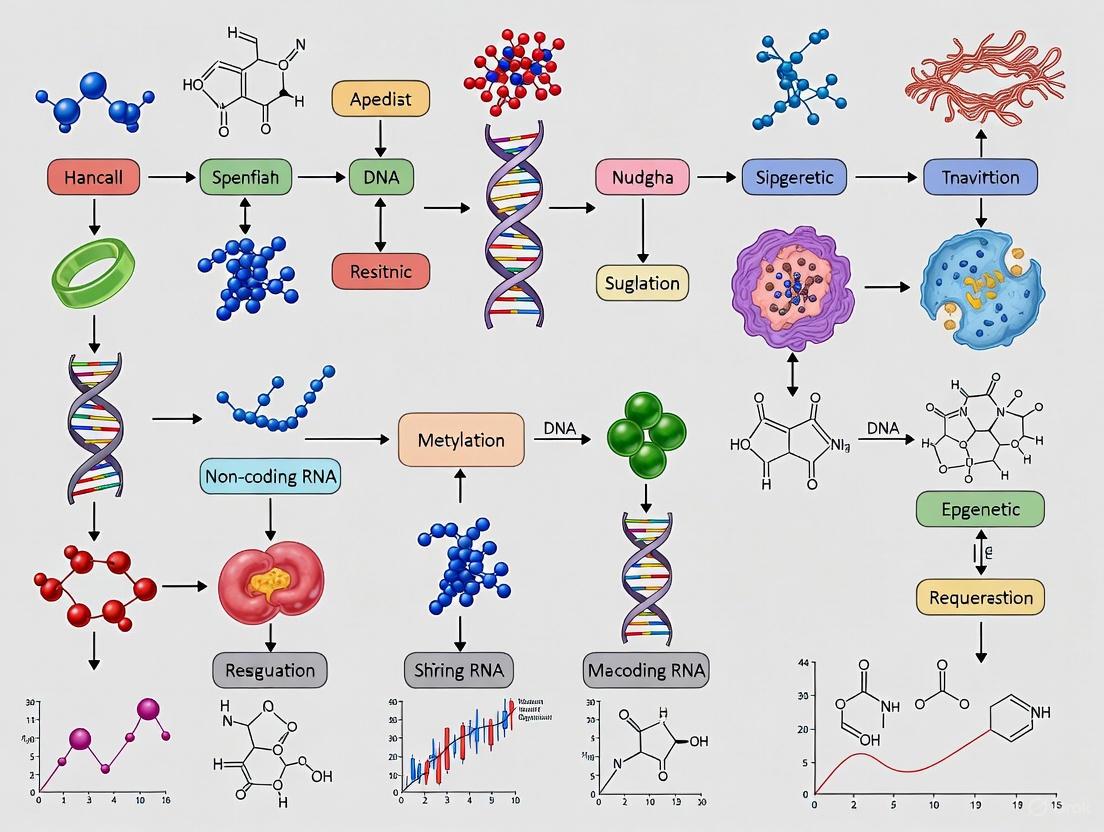

Figure 1: Interplay of Epigenetic Mechanisms in Cancer Pathogenesis. This diagram illustrates how the three principal epigenetic mechanisms contribute to cancer hallmarks through specific dysregulations, ultimately driving tumor development and therapeutic resistance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Epigenetic Cancer Research

| Category | Specific Reagents/Tools | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Analysis | Bisulfite Conversion Kits (EZ DNA Methylation kits) | Convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils for methylation detection | Conversion efficiency controls are critical |

| Methylation-Sensitive Restriction Enzymes (HpaII, MspI) | Differential digestion based on methylation status | Requires careful optimization of digestion conditions | |

| Anti-5-methylcytosine Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of methylated DNA | Antibody specificity validation essential | |

| Histone Modification Studies | Modification-Specific Histone Antibodies (anti-H3K27ac, anti-H3K4me3, etc.) | ChIP-seq, Western blot, immunofluorescence | Rigorous validation using peptide arrays recommended |

| Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors (Trichostatin A, Vorinostat) | Functional studies of acetylation in cellular models | Off-target effects should be controlled | |

| Histone Methyltransferase Inhibitors (UNC0638, GSK126) | Investigate specific methylation pathways | Cellular permeability varies by compound | |

| Chromatin Remodeling | ATPase Inhibitors (BAY-850, AM-879) | Probe remodeling complex function | Often lack specificity for individual complexes |

| Crosslinking Reagents (formaldehyde, DSG) | Stabilize protein-DNA interactions for ChIP | Crosslinking conditions require optimization | |

| Cryo-EM Reagents (Grids, Vitrification devices) | Structural studies of remodeling complexes | Technical expertise intensive methodology | |

| Integrated Epigenetic Analysis | 4f-SAMMY-seq Reagents [14] | Chromatin compartment analysis from biopsies | Requires fresh tissue samples |

| ATAC-seq Kit (Illumina) | Mapping open chromatin regions | Works well with low cell numbers | |

| Multi-omics Integration Platforms | Simultaneous analysis of multiple epigenetic layers | Computational expertise required |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The field of cancer epigenetics continues to evolve rapidly, with emerging research areas including the role of RNA modifications in epigenetic regulation [16], the influence of three-dimensional genome organization on cancer gene expression [14], and the development of increasingly sophisticated epigenetic editing technologies.

Recent discoveries of genetic sequences that can direct DNA methylation patterns represent a paradigm shift in understanding what regulates epigenetics [17]. This finding that specific DNA sequences can recruit methylation machinery opens new possibilities for precisely correcting epigenetic defects to improve human health [17].

As single-cell epigenetic technologies mature, they promise to reveal unprecedented details about epigenetic heterogeneity within tumors, potentially identifying new therapeutic targets and biomarkers for personalized cancer treatment [9] [10]. The integration of epigenetic approaches with conventional therapies holds particular promise for overcoming drug resistance and improving patient outcomes across a spectrum of malignancies.

The principal epigenetic mechanisms of DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling form an interconnected regulatory network that governs gene expression patterns without altering DNA sequence. Their dysregulation contributes fundamentally to cancer development through the creation of epigenetic heterogeneity that drives tumor evolution and therapeutic resistance. Continued investigation of these mechanisms will undoubtedly yield new insights into cancer biology and novel approaches for cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Epigenetic regulation, which involves reversible and heritable changes in gene expression that occur without altering the DNA sequence, represents a critical interface between genetic predisposition and environmental influence in cancer development [18]. The concept of "epigenetic heterogeneity" has emerged as a fundamental principle in oncology, providing a mechanistic basis for tumor evolution, therapeutic resistance, and disease progression [19] [20]. This heterogeneity arises from a complex interplay of stochastic (random) and deterministic (directed) processes that shape the epigenome. Stochastic processes introduce random epigenetic variation through molecular noise in biochemical reactions, imperfect maintenance of epigenetic marks during cell division, and spontaneous epimutations [21] [22]. In contrast, deterministic processes impose directed epigenetic changes through environmental exposures, cellular signaling pathways, and metabolic reprogramming [20]. Understanding the balance between these forces is essential for deciphering cancer evolution and developing effective epigenetic therapies. This whitepaper examines the origins and consequences of epigenetic heterogeneity in cancer, with particular focus on the technical approaches for dissecting stochastic and deterministic contributions to the cancer epigenome.

Theoretical Framework: Stochasticity vs. Determinism in Epigenetic States

The Spectrum of Epigenetic Inheritance

Epigenetic information is transmitted through cell divisions via multiple molecular mechanisms, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin architecture. The fidelity of this transmission varies considerably across the genome and can be influenced by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Theoretical models and experimental evidence suggest that epigenetic states exist along a spectrum of stability, with some regions exhibiting high fidelity maintenance and others demonstrating considerable plasticity [22].

The stability of any given epigenetic state is governed by the balance between reinforcing mechanisms (such as the cooperative binding of modifying enzymes and positive feedback loops) and destabilizing forces (including stochastic fluctuations in enzyme concentrations and random partitioning during DNA replication). This balance can be mathematically modeled to predict the likelihood of epigenetic switching events, which have been implicated in cellular plasticity and phenotype transitions in cancer [22].

Quantitative Contributions of Stochastic Processes

Recent advances in single-cell epigenomic technologies have enabled researchers to quantify the stochastic component of epigenetic changes. A 2024 study systematically analyzed the stochastic nature of epigenetic aging by building realistic simulation models of DNA methylation changes [23]. The research demonstrated that 66-75% of the accuracy underpinning Horvath's epigenetic clock could be driven by a stochastic process of DNA methylation change, with this fraction increasing to 90% for more accurate clocks like Zhang's clock [23].

Table 1: Stochastic Components of Epigenetic Clocks in Cancer Aging

| Epigenetic Clock | Stochastic Component | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Horvath's Clock | 66-75% | Primarily measures stochastic accumulation of epigenetic errors |

| Zhang's Clock | ~90% | Mainly captures stochastic processes with high chronological accuracy |

| PhenoAge Clock | ~63% | Reflects more non-stochastic, biological aging processes |

These findings suggest that a substantial portion of age-associated epigenetic changes, a known cancer risk factor, occur through stochastic mechanisms. However, the research also identified that epigenetic age acceleration in specific clinical contexts (such as severe COVID-19 cases and smokers) is driven predominantly by non-stochastic processes, highlighting the complex interplay between random and directed epigenetic changes in disease states [23].

Epigenetic Heterogeneity in Cancer Development

Intraindividual Heterogeneity in Advanced Cancers

Comprehensive multi-omic profiling of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) tumors has revealed striking patterns of epigenetic heterogeneity within individual patients [19]. A 2025 study performed combined DNA methylation, RNA-sequencing, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3 profiling across metastatic lesions from patients with CRPC and neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC), including rapid autopsy cases with multiple anatomic sites from individual patients [19].

The study identified that while global methylation profiles were generally conserved across metastases within the same patient, significant epigenetic heterogeneity existed in specific genomic regions linked to phenotypic diversity [19]. Notably, five patients exhibited more than one molecular subtype (AR+/NE-, AR-low/NE-, AR-/NE-, AR-/NE+, AR+/NE+) across different metastatic sites, indicating substantial intraindividual heterogeneity [19]. Patient-specific clustering analyses based on DNA methylation revealed clear separation between tumors of different subtypes, suggesting that differences in DNA methylation underlie molecular transitions during cancer progression [19].

The Concept of "Epigenome Chaos" in Cancer Evolution

Cancer evolution is characterized by what has been termed "epigenome chaos" – a state of profound epigenetic disorganization characterized by seemingly random yet strongly selected epigenetic alterations [20]. This chaos manifests as widespread dysregulation of DNA methylation patterns, including promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes, global genomic hypomethylation, loss of imprinting, and aberrant expression of developmental genes [20].

The "epigenome chaos" concept integrates both stochastic and deterministic elements: epigenetic changes are initially generated through stochastic mechanisms, but are subsequently refined through deterministic selection pressures (such as chemoresistance, hypoxia, and immune evasion) [20]. This model helps explain the paradoxical observation that cancer epigenomes display both predictable patterns (such as consistent hypermethylation of specific tumor suppressor genes) and extensive, apparently random heterogeneity.

Table 2: Characteristics of Epigenetic Alterations in Cancer

| Feature | Stochastic Origins | Deterministic Origins |

|---|---|---|

| Timing | Continuous, aperiodic | Often associated with specific cancer stages |

| Pattern | Repetitive, sensitive to initial conditions | Context-dependent, selected for fitness advantage |

| Selection | Neutral evolution | Darwinian selection for adaptive traits |

| Therapeutic implications | Contributes to general heterogeneity | Can drive specific resistance mechanisms |

Methodologies for Dissecting Stochastic and Deterministic Components

Integrated Multi-Omic Profiling

The 2025 prostate cancer study established a comprehensive methodological framework for integrating multiple epigenetic datasets to distinguish stochastic from deterministic epigenetic variation [19]. The approach involved:

Sample Collection: 98 tumor tissue samples from 35 patients with metastatic CRPC (9 NEPC and 26 CRPC-Adeno), with tissues from 21 patients obtained at rapid autopsy with multiple anatomic sites assessed (median 4 sites per patient) [19].

Multi-Omic Profiling:

- Genome-wide DNA methylation by reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS)

- RNA-sequencing for transcriptomic analysis

- H3K27ac and H3K27me3 profiling via ChIP-seq or CUT&Tag on 35 samples [19]

Bioinformatic Integration:

- CpG sites were grouped within 200 base pairs and clusters with three or more CpGs were selected (~300,000 regions)

- Regions classified into four categories: H3K27ac-associated, H3K27me3-associated, promoters, or gene bodies

- Correlation analysis between DNA methylation and gene expression identified 21,721 significant region-gene links [19]

This integrated approach revealed distinct correlation patterns: most genes linked with H3K27ac-associated regions showed negative correlation between expression and DNA methylation, while 70% of genes linked with H3K27me3-associated regions exhibited positive correlation [19].

Multi-Omic Workflow for Epigenetic Analysis

Quantitative Modeling of Epigenetic Switching

A 2024 study developed a theoretical framework to compute epigenetic switching rates driven by DNA replication [22]. This hybrid stochastic-deterministic approach models:

- Deterministic Components: Histone modification dynamics during most of the cell cycle

- Stochastic Components: Random distribution of nucleosomes between daughter DNA strands during replication

The model enables analytic derivation of replication-driven switching rates and can explain experimental data on epigenetic state transitions [22]. This framework is particularly valuable for understanding how apparently stable epigenetic states can undergo spontaneous transitions during tumor evolution, contributing to cellular heterogeneity without genetic changes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Epigenetic Heterogeneity Studies

| Reagent/Technology | Primary Function | Application in Cancer Epigenetics |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis | Identifies variable methylation patterns across tumor samples [19] |

| CUT&Tag/ChIP-seq | Mapping histone modifications | Profiles H3K27ac (active enhancers) and H3K27me3 (repressive) marks [19] |

| Single-cell RNA-sequencing | Transcriptomic profiling at single-cell resolution | Reveals cellular heterogeneity and rare subpopulations in tumors |

| DNA methylation arrays (Illumina) | Targeted methylation analysis | Enables epigenetic clock construction and age acceleration studies [23] |

| CRISPR-based epigenetic editors | Targeted manipulation of epigenetic marks | Functional validation of epigenetic regulatory elements |

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks

Epigenetic Regulation of Lineage Plasticity

In advanced prostate cancer, integrated epigenomic analyses have revealed how stochastic and deterministic epigenetic changes drive lineage plasticity and treatment resistance [19]. The study identified DNA methylation-driven gene links based on genomic location (H3K27ac, H3K27me3, promoters, gene bodies) that point to mechanisms underlying dysregulation of genes involved in tumor lineage (ASCL1, AR) and therapeutic targets (PSMA, DLL3, STEAP1, B7-H3) [19].

For example, a region 7 kilobases upstream of the NE-lineage gene ASCL1 exhibited a strong positive correlation between ASCL1 mRNA expression and H3K27ac signal, while showing a negative correlation with DNA methylation levels [19]. This pattern illustrates how deterministic selection (for neuroendocrine differentiation) can leverage stochastic epigenetic variation to drive phenotypic evolution.

Competing Influences on Epigenetic States

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Opportunities

Diagnostic and Prognostic Applications

The recognition of substantial epigenetic heterogeneity in cancers has important implications for diagnostic approaches. Traditional single-site biopsies may fail to capture the full spectrum of epigenetic diversity within a patient's disease [19]. The identification of patient-specific epigenetic signatures that are conserved across metastases, however, suggests that liquid biopsy approaches targeting these stable patient-specific patterns could provide more comprehensive diagnostic information [19].

From a prognostic standpoint, the balance between stochastic and deterministic epigenetic processes has clinical relevance. Cancers with predominantly stochastic epigenetic heterogeneity may follow more unpredictable clinical courses, while those with strong deterministic components might exhibit more consistent patterns of progression that are potentially more amenable to targeted interventions.

Therapeutic Strategies and Resistance Mechanisms

The conceptual framework of "epigenome chaos" has direct implications for cancer therapy [20]. While targeted epigenetic therapies (such as DNA methyltransferase inhibitors or histone deacetylase inhibitors) can reverse specific deterministic epigenetic alterations, their effectiveness may be limited in highly stochastic epigenomes where rapid adaptation can occur through pre-existing heterogeneous epigenetic states.

Combination approaches that simultaneously target both the deterministic drivers (through pathway-specific inhibitors) and the overall epigenetic plasticity (through broader epigenetic modulators) may be required to achieve durable responses. Additionally, understanding the stochastic components of epigenetic aging may inform strategies for cancer prevention and early detection [23].

The integration of stochastic and deterministic frameworks provides a more comprehensive understanding of epigenetic heterogeneity in cancer development. While stochastic processes generate the raw material for epigenetic evolution through random epimutations and imperfect maintenance mechanisms, deterministic forces shape this variation through selection for fitness advantages in specific microenvironmental contexts [19] [20].

Future research directions should include:

- Development of more sophisticated computational models that can quantitatively partition epigenetic variation into stochastic and deterministic components

- Longitudinal studies tracking epigenetic dynamics throughout cancer progression and treatment

- Single-cell multi-omic technologies that simultaneously capture epigenetic and transcriptomic states in individual cells

- Therapeutic strategies that specifically target the vulnerable nodes in epigenetic regulatory networks

As the field advances, the conceptual integration of stochastic and deterministic origins of epigenetic states will likely yield novel insights into cancer biology and therapeutic opportunities, ultimately enabling more effective targeting of epigenetic heterogeneity in clinical oncology.

Epigenetic dysregulation is a foundational event in the earliest stages of carcinogenesis, establishing pre-malignant "field defects" that prime tissue for neoplastic transformation. This whitepaper synthesizes current research on the initiating role of epigenetic alterations—including DNA methylation anomalies, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling—in creating oncogenic-prone cellular landscapes. We detail the mechanistic drivers of epigenetic field cancerization and their contribution to tumor heterogeneity. Supported by quantitative data and experimental methodologies, this review provides a technical resource for researchers and drug development professionals targeting the epigenetic origins of cancer. The reversible nature of these alterations presents a promising therapeutic avenue for early intervention and cancer prevention strategies.

The concept of "field cancerization," first introduced by Slaughter et al. in 1953, describes the occurrence of multifocal areas of precancerous change and abnormal tissue surrounding primary tumors [2]. Contemporary research has established that epigenetic dysregulation is a principal mechanistic driver of this phenomenon, creating a permissive microenvironment for clonal expansion and tumor initiation [2]. Unlike genetic mutations, epigenetic modifications are heritable yet reversible changes in gene expression that do not alter the underlying DNA sequence, positioning them at the interface between environmental exposures and cellular transformation [24] [25].

In early carcinogenesis, the accumulation of aberrant epigenetic marks precedes and often outweighs genetic alterations [24]. This is characterized by a fundamental reprogramming of the epigenome that affects chromatin architecture, DNA accessibility, and, ultimately, cellular identity. The dysregulation of the "epigenetic machinery"—comprising "writer," "reader," and "eraser" proteins—establishes a pre-malignant field marked by transcriptional plasticity and heterogeneity [24] [6]. This epigenetic instability provides a fertile ground for the selection and expansion of initiated clones, setting the stage for invasive carcinoma. Understanding these earliest epigenetic events is crucial for developing biomarkers for risk stratification and novel chemopreventive strategies.

Core Mechanisms of Epigenetic Dysregulation

Epigenetic dysregulation in early carcinogenesis manifests through several interconnected mechanisms. The coordinated dysregulation of these systems disrupts normal gene expression patterns, silences tumor suppressor genes (TSGs), and promotes genomic instability, collectively driving the initiation of cancer.

DNA Methylation Anomalies

DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of cytosine in CpG dinucleotides, catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) [24] [26]. This process is critical for maintaining genomic integrity and controlling gene expression.

- CpG Island Hypermethylation: Promoters of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) are often enriched in CpG islands (CGIs). In cancer, these normally unmethylated regions undergo focal hypermethylation, leading to transcriptional silencing of associated genes [24] [26]. This silencing is further reinforced by a shift to a more compact chromatin state [24].

- Global Hypomethylation: In contrast to focal hypermethylation, genomic-wide hypomethylation is a hallmark of cancer cells. This loss of methylation, particularly in repetitive elements and intergenic regions, leads to genomic instability and can activate oncogenes and transposable elements [24] [26].

- Enzymatic Drivers and Active Demethylation: De novo methylation patterns are established by DNMT3A and DNMT3B, while DNMT1 maintains these patterns during DNA replication [24] [26]. The Ten-eleven translocation (TET) family of enzymes (TET1, TET2, TET3) catalyzes the active demethylation of DNA by oxidizing 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and other derivatives [24] [2]. Downregulation of TET proteins and the consequent loss of 5hmC are recognized as early epigenetic hallmarks in human cancer [2].

Table 1: Key Enzymes in DNA Methylation and Their Roles in Early Carcinogenesis

| Enzyme | Primary Function | Role in Early Carcinogenesis | Associated Cancers |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Maintenance methylation during DNA replication | Perpetuates aberrant methylation patterns in proliferating pre-cancerous cells | Widespread across cancer types [26] |

| DNMT3A / DNMT3B | De novo methylation | Establishes new, aberrant methylation marks on previously unmethylated DNA, silencing TSGs | Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) [26] |

| TET2 | Active DNA demethylation | Loss of function reduces 5hmC levels, contributing to a hypermethylated phenotype and silencing of TSGs | AML, Myelodysplastic Syndromes [26] [2] |

Histone Modifications and Chromatin Remodeling

The post-translational modification of histone tails and the ATP-dependent repositioning of nucleosomes are critical for regulating chromatin topology and gene expression. Dysregulation of these processes is a key feature of early carcinogenesis.

- Histone Modification Imbalances: Histone acetylation, mediated by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and erased by histone deacetylases (HDACs), is generally associated with an open, transcriptionally active chromatin state [26]. In cancer, a loss of acetyl marks (e.g., H4K16Ac) can contribute to silencing of TSGs [24]. Similarly, specific histone methylation marks can be activating (e.g., H3K4me3) or repressive (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K9me3). Dysregulation of the enzymes responsible for these marks, such as histone methyltransferases and demethylases (e.g., KDM6/4), is frequently observed [24].

- Chromatin Remodeling Complex Mutations: Mutations in subunits of chromatin remodeling complexes, such as SWI/SNF (Switch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable), ISWI (Imitation Switch), and CHD (Chromodomain-Helicase-DNA-binding), are common in cancer [24] [26]. These loss-of-function mutations impair nucleosome repositioning, which can prevent effective DNA damage sensing and repair, and alter the expression of genes critical for cell fate decisions [26].

The "Writers," "Readers," and "Erasers" Framework

The "epigenetic machinery" can be conceptually organized into three functional classes that dynamically control the epigenome:

- Writers: Enzymes that establish epigenetic marks (e.g., DNMTs, HATs, histone methyltransferases).

- Erasers: Enzymes that remove these marks (e.g., TETs, HDACs, histone demethylases).

- Readers: Proteins that recognize and bind to specific epigenetic marks, translating them into a functional chromatin state (e.g., bromodomain-containing proteins that bind acetylated lysines) [24] [6].

Dysregulation at any of these three levels can disrupt the intricate balance of the epigenetic landscape, leading to the aberrant gene expression programs that underlie field defect formation and tumor initiation.

Epigenetic Field Defects: Mechanisms and Measurement

The concept of the epigenetic field defect provides a mechanistic basis for understanding how apparently normal tissue can be predisposed to multifocal tumor development.

Establishing the Pre-Malignant Field

The accumulation of aberrant epigenetic changes in histologically normal tissue creates a "field" that is conducive to cancer development. Our previous studies of normal esophageal mucosa, dysplasia, and carcinoma demonstrate that the accumulation of aberrant promoter methylation in TSGs occurs in a stepwise manner, similar to the classic model of mutational accumulation [2]. This epigenetic reprogramming occurs in response to environmental insults (e.g., smoking, inflammation) and can be both transient and persistent [24]. The resulting field is characterized by:

- TSG Silencing: Hypermethylation and subsequent silencing of key TSGs, providing initiated cells with a selective growth advantage [2].

- Increased Plasticity and Heterogeneity: The altered epigenome increases cellular plasticity, allowing for the emergence of diverse subpopulations and fostering intratumor heterogeneity (ITH) even before a tumor is fully formed [2].

Quantitative Analysis of Field Defects

The measurement of epigenetic changes in field defects relies on sensitive techniques that can detect abnormalities in bulk tissue or single cells.

Table 2: Quantitative Profiling of Epigenetic Alterations in Field Defects

| Analysis Method | Target | Key Findings in Field Defects | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-wide Methylation Array (e.g., 450K/850K) | Methylation status of hundreds of thousands of CpG sites | Identification of differentially methylated regions (DMRs) and CpG islands (CGIs); increased epigenetic entropy [27] | Requires bulk tissue; provides an average methylation level across cell populations |

| Bisulfite Sequencing (Whole-genome or Targeted) | Base-resolution methylation status | High-resolution mapping of hyper/hypomethylated loci; can be applied to liquid biopsies for early detection [24] | Gold standard for methylation analysis; computationally intensive |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq) | Histone modifications (e.g., H3K27ac, H3K4me3) and chromatin-associated proteins | Reveals shifts in enhancer and promoter activity; identifies imbalances in activating/repressive marks [24] | Requires high-quality antibodies and deep sequencing |

| Super-Resolution Microscopy (e.g., STORM) | Nanoscale chromatin organization in intact tissues | Detects chromatin fragmentation and decompaction as an early event in carcinogenesis, even in morphologically normal cells [28] | Enables direct visualization of chromatin structure; technically challenging for high-throughput |

The Emergence of Heterogeneity and Plasticity

The pre-malignant field is not a uniform entity. Epigenetic heterogeneity within the field is a critical source of cellular plasticity, enabling the adaptation and evolution of nascent tumor cells. Research using advanced imaging has revealed that chromatin disruption, marked by open and fragmented structures, is a universal and early event across cancer types, occurring even before morphological changes are evident [28]. This chromatin decompaction is believed to break down the protective, condensed structure of the genome, making cells more susceptible to environmental insults and facilitating malignant transformation by allowing aberrant access to transcription factors [28]. This epigenetic state supports the development of hybrid cellular states and enhances the tumor's capacity to adapt to therapeutic pressures and the immune microenvironment [29].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Dissecting the role of epigenetics in early carcinogenesis requires a combination of sophisticated molecular techniques, imaging, and computational models.

Super-Resolution Imaging of Chromatin Organization

Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy (STORM) is a fluorescence imaging technique that bypasses the diffraction limit of light, allowing for visualization of chromatin organization at a resolution of 20-30 nm [28].

- Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Tissue sections (e.g., from patient-derived paraffin-embedded samples) are stained with a DNA-intercalating fluorescent dye.

- Stochastic Blinking: The imaging buffer induces random, stochastic "blinking" of a sparse subset of fluorescent molecules at any given time.

- Image Acquisition: Tens of thousands of frames are collected to capture the precise locations of all blinking molecules.

- Image Reconstruction: A super-resolution image is computationally reconstructed from the accumulated localization data [28].

- Key Findings: Application of STORM to patient tissues across cancer progression (e.g., colon, prostate, lung) has universally revealed open and disrupted chromatin structures in tumor cells. The most significant chromatin fragmentation occurs at the earliest stages of carcinogenesis, preceding tumor formation [28].

Measuring Tumor Mitotic Age with Stochastic Epigenetic Clocks

Conventional "one-way" epigenetic clocks measure age-related methylation increases. In contrast, "two-way" or stochastic epigenetic clocks estimate tumor mitotic age based on the entropy of an ensemble of fluctuating CpG (fCpG) sites.

- Protocol:

- Identification of Unbiased fCpG Sites: Using genome-wide methylation array data (e.g., from TCGA), select CpG sites with an average β-value close to 0.5 in both normal and tumor tissues, indicating balanced methylation/demethylation rates [27].

- Selection of Most Fluctuating Sites: Rank unbiased CpG sites by between-tumor variability and select the top 500 most fluctuating sites for the final clock.

- Calculation of Epigenetic Clock Index: For a given tumor, the clock index ( c{\beta} ) is calculated as ( c{\beta} = 1 - s{\beta} ), where ( s{\beta} ) is the standard deviation of the β-values of the 500 fCpG sites. A higher ( c_{\beta} ) indicates greater mitotic age [27].

- Biological Insight: This clock is reset at the onset of tumor growth. It reveals that younger, fast-growing tumors are associated with aggressiveness (e.g., genomic instability), while older tumors show elevated immune infiltration, capturing the tumor's evolutionary history [27].

Profiling the Field Defect

To map the epigenetic landscape of a field defect, multi-region sampling and deep sequencing are required.

- Protocol for Multi-Region Methylation Analysis:

- Sample Collection: Obtain multiple biopsies from the primary tumor site, surrounding histologically normal tissue (e.g., >1cm from margin), and matched normal tissue (e.g., blood).

- DNA Extraction and Bisulfite Conversion: Treat genomic DNA with bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain as cytosines.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries from the converted DNA for whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) or targeted approaches.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map sequencing reads to a reference genome and calculate methylation levels for each CpG. Identify DMRs between normal, field, and tumor tissues. Phylogenetic trees can be constructed to model the clonal evolution of epigenetic alterations [2].

Visualizing Epigenetic Pathways and Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows discussed in this review.

Epigenetic Dysregulation in Field Cancerization

Stochastic Epigenetic Clock Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Advancing research in epigenetic field defects requires a specialized set of reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for investigating these early events in carcinogenesis.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Epigenetic Field Defects

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application in Field Defect Research |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors (e.g., 5-Azacytidine, Decitabine) | Nucleoside analogs that incorporate into DNA and inhibit DNMT activity, leading to DNA hypomethylation. | Reversal of hypermethylation and reactivation of silenced tumor suppressor genes in pre-malignant models [25] [26]. |

| Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors (e.g., Vorinostat, Romidepsin) | Small molecule inhibitors of HDAC enzymes, promoting histone hyperacetylation and a more open chromatin state. | Studying the role of histone acetylation in gene reactivation and cellular differentiation in field defects [25] [26]. |

| TET Enzyme Activators | Small molecules (e.g., Vitamin C) that can enhance TET enzyme activity, promoting DNA demethylation. | Experimental models to assess the functional impact of restoring 5hmC levels and reversing hypermethylation in pre-cancerous fields [2]. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Chemical treatment that converts unmethylated cytosine to uracil for downstream sequencing-based methylation analysis. | Gold-standard method for mapping DNA methylation patterns at single-base resolution in normal, field, and tumor tissues [27]. |

| Anti-5hmC / Anti-5mC Antibodies | Highly specific antibodies for immunodetection of cytosine modifications (e.g., immunofluorescence, dot blot). | Quantifying the global loss of 5hmC (TET dysfunction) and redistribution of 5mC in tissue sections comprising field defects [2]. |

| Unbiased fCpG Panel | A predefined set of ~500 fluctuating CpG sites identified from genome-wide arrays. | Application of the stochastic epigenetic clock to estimate the mitotic age of early lesions and quantify epigenetic entropy [27]. |

The evidence is unequivocal: epigenetic dysregulation is a driving force in early carcinogenesis, creating widespread field defects that predispose to cancer development. The reversible nature of epigenetic marks, coupled with their early appearance, makes them attractive targets for interception and prevention strategies. Future progress will depend on leveraging multi-omics technologies to deconvolute the complex epigenetic networks that underlie field defects and tumor heterogeneity. The integration of spatial multi-omics will be particularly transformative, providing the spatial coordinates of epigenetic and cellular heterogeneity within the tissue architecture [6]. Furthermore, the development of more sensitive liquid biopsy assays capable of detecting methylation signatures from field defects holds immense promise for the early detection of cancer and risk stratification [24]. As our understanding deepens, the combination of epigenetic therapies with other modalities, such as immunotherapy or targeted agents, presents a compelling strategy to reverse or delay the progression of pre-malignant fields, heralding a new era in precision cancer prevention [25] [6].

Epigenetic heterogeneity is a fundamental characteristic of human cancers that drives phenotypic and functional diversity, serving as a key engine for tumor progression and therapeutic resistance [30]. This heterogeneity manifests at multiple levels: interpatient heterogeneity (variations between tumors from different patients), intra-patient heterogeneity (variations between multiple tumors of the same type in the same patient), and intratumor heterogeneity (ITH) (subpopulations of cancer cells with distinct molecular features within a single tumor) [30]. Within a tumor, diversity exists in cancer cell proliferation, immune infiltration, differentiation status, and necrosis that can differ between microscopy fields [30]. The phenomenon of ITH is commonly explained by Darwinian-like clonal evolution, where despite the monoclonal origin of most cancers, new clones arise during tumor progression due to continuous acquisition of mutations and epigenetic alterations [30].

The epigenome resides at the intersection of the environment and genome, with epigenetic dysregulation occurring in the earliest stages of cancer development [30]. Aberrant epigenetic changes occur more frequently than gene mutations in human cancers, making them a prime driver of malignant transformation [30] [31]. Unlike genetic mutations, epigenetic modifications are dynamic and reversible, allowing cancer cells to adapt to therapeutic pressures and microenvironmental challenges [6] [32]. This plasticity enables transitions between cell states—a phenomenon particularly evident in cancer stem cells (CSCs)—and provides a reservoir of cellular states that facilitate drug-resistance adaptation [32]. Each cell state reflects a distinct configuration of gene regulatory networks emerging from the complex interplay between chromatin structure, transcription factors, and gene expression [32].

Epigenetic Mechanisms Driving Cancer Heterogeneity

DNA Methylation Heterogeneity

DNA methylation represents a crucial epigenetic modification involving the addition of a methyl group to specific bases within DNA, predominantly at the fifth carbon of cytosine in CpG islands to form 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [6]. This modification serves as a physical barrier that hinders transcription factors from binding to genes, ultimately leading to transcriptional repression through the formation of compact heterochromatin [6]. The ten-eleven translocation (TET) proteins can successively oxidize 5mC to form derivatives including 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC), which are associated with active gene expression [30] [6]. Downregulation of TET proteins and subsequent loss of 5hmC are now recognized as new epigenetic hallmarks of human cancer [30].