Foundation Models vs. Traditional Transfer Learning in Computational Pathology: A New Paradigm for Precision Oncology

The emergence of foundation models is fundamentally reshaping the artificial intelligence landscape in computational pathology.

Foundation Models vs. Traditional Transfer Learning in Computational Pathology: A New Paradigm for Precision Oncology

Abstract

The emergence of foundation models is fundamentally reshaping the artificial intelligence landscape in computational pathology. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, contrasting the new paradigm of large-scale, self-supervised foundation models against established traditional transfer learning approaches. We explore the foundational principles of both methodologies, detail their practical applications in biomarker discovery and cancer diagnostics, systematically address critical challenges including robustness and clinical integration, and present rigorous comparative performance data from recent large-scale benchmarks. The analysis synthesizes evidence that while foundation models offer unprecedented generalization capabilities and data efficiency, their successful clinical adoption requires overcoming significant hurdles in validation, interpretability, and computational infrastructure.

Defining the Paradigm Shift: From Task-Specific AI to General-Purpose Foundations in Pathology

Computational pathology stands at the forefront of a revolution in diagnostic medicine, leveraging artificial intelligence to extract clinically relevant information from high-resolution whole-slide images (WSIs) that would otherwise be imperceptible to the human eye [1]. Traditional approaches have predominantly relied on transfer learning from models pre-trained on natural image datasets like ImageNet—a method that involves adapting a model developed for one task to a new, related task [2]. While this strategy has enabled initial forays into AI-assisted pathology, it suffers from two fundamental constraints: an insatiable demand for labeled data and narrow task specialization that limits clinical applicability [3] [2].

The emergence of pathology foundation models represents a transformative response to these limitations. Trained through self-supervised learning on millions of pathology-specific images, these models learn universal visual representations of histopathology that capture the intricate patterns of tissue morphology, tumor microenvironment, and cellular architecture [4]. Unlike their traditional counterparts, foundation models demonstrate remarkable domain adaptability and can be efficiently fine-tuned for diverse clinical tasks with minimal additional data, effectively addressing the core constraints of data hunger and narrow specialization [3] [4]. This comparison guide examines the performance differential between these approaches through rigorous experimental evidence, providing researchers and drug development professionals with objective data to inform their computational pathology strategies.

Experimental Frameworks for Comparison

Benchmarking Study Design and Model Selection

To quantitatively assess the performance gap between traditional transfer learning and foundation models, we draw upon a comprehensive independent benchmarking study that evaluated 19 foundation models across 13 patient cohorts comprising 6,818 patients and 9,528 slides [4]. The experimental design employed a rigorous weakly-supervised learning framework across 31 clinically relevant tasks categorized into three domains: morphological assessment (5 tasks), biomarker prediction (19 tasks), and prognostic outcome forecasting (7 tasks) [4]. This extensive validation approach mitigates the risk of data leakage and selective reporting that has plagued earlier, narrower evaluations.

The benchmarked models represent the two predominant paradigms in computational pathology. The traditional transfer learning approach was represented by ImageNet-pre-trained convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which serve as the established baseline in the field [3]. These were compared against vision-language foundation models (CONCH, PLIP, BiomedCLIP) and vision-only foundation models (Virchow2, UNI, Prov-GigaPath, DinoSSLPath) trained using self-supervised learning on large-scale histopathology datasets [4]. Performance was measured using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), with supplementary metrics including area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC), balanced accuracy, and F1 scores to ensure comprehensive assessment [4].

Cross-Domain Performance Evaluation Protocol

The evaluation methodology employed a multiple instance learning (MIL) framework with transformer-based aggregation to handle whole-slide image processing [4]. Each model was evaluated as a feature extractor, with the encoded embeddings serving as inputs to task-specific prediction heads. This approach mirrors real-world clinical implementation where models must generalize across varied tissue types, staining protocols, and scanner specifications [4]. To assess robustness in data-scarce environments—a critical limitation of traditional transfer learning—additional experiments were conducted with progressively reduced training set sizes (300, 150, and 75 patients) while maintaining the original positive-to-negative case ratios [4].

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Benchmarking Foundation Models. The evaluation pipeline processes whole slide images through standardized preprocessing before extracting features using foundation models and making predictions on clinically relevant tasks.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Foundation models demonstrated superior performance across all clinical domains when compared to traditional transfer learning approaches. As shown in Table 1, the vision-language foundation model CONCH achieved the highest mean AUROC (0.71) across all 31 tasks, followed closely by the vision-only foundation model Virchow2 (0.71) [4]. This represents a significant performance advantage over traditional ImageNet-based transfer learning, which typically achieves AUROCs between 0.60-0.65 on similar tasks [3]. The performance differential was most pronounced in morphological assessment tasks, where CONCH achieved an AUROC of 0.77 compared to approximately 0.65-0.70 for traditional approaches [4].

Table 1: Performance Comparison Across Clinical Domains

| Model Category | Specific Model | Morphology AUROC | Biomarkers AUROC | Prognosis AUROC | Overall AUROC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vision-Language Foundation | CONCH | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.71 |

| Vision-Only Foundation | Virchow2 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.61 | 0.71 |

| Vision-Only Foundation | Prov-GigaPath | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 0.69 |

| Vision-Only Foundation | DinoSSLPath | 0.76 | 0.69 | 0.60 | 0.69 |

| Traditional Transfer Learning | ImageNet-based CNN | ~0.65-0.70* | ~0.63-0.68* | ~0.55-0.60* | ~0.60-0.65* |

Note: Traditional transfer learning performance estimated from comparative analyses in [3] and [4]

Data Efficiency in Low-Resource Scenarios

A critical limitation of traditional transfer learning is its data hunger—the requirement for substantial labeled examples to achieve acceptable performance. Foundation models substantially mitigate this constraint through their pre-training on vast histopathology datasets [4]. When evaluated with limited training data (75 patients), foundation models maintained robust performance, with CONCH, PRISM, and Virchow2 leading in 5, 4, and 4 tasks respectively [4]. This stands in stark contrast to traditional approaches, which typically experience performance degradation of 15-20% when training data is reduced to similar levels [3].

The data efficiency of foundation models stems from their diverse pre-training corpora. For instance, Virchow2 was trained on 3.1 million WSIs, while CONCH incorporated 1.17 million image-caption pairs curated from biomedical literature [4] [5]. This extensive exposure to histopathological variations enables the models to learn universal visual representations that transfer efficiently to new tasks with minimal fine-tuning. Correlation analyses revealed that data diversity (measured by tissue site variety) in pre-training datasets showed stronger correlation with downstream performance (r=0.74, p<0.05) than sheer data volume alone [4].

Table 2: Data Efficiency Comparison Across Training Set Sizes

| Model Type | Large Cohort (n=300) Performance | Medium Cohort (n=150) Performance | Small Cohort (n=75) Performance | Performance Retention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vision-Language Foundation (CONCH) | Leads in 3 tasks | Leads in 4 tasks | Leads in 5 tasks | ~95% |

| Vision-Only Foundation (Virchow2) | Leads in 8 tasks | Leads in 6 tasks | Leads in 4 tasks | ~90% |

| Traditional Transfer Learning | Competitive in 1-2 tasks | Significant degradation | Severe degradation | ~70-80% |

Task-Specific Performance on Critical Biomarkers

Foundation models demonstrated particular strength in predicting molecular biomarkers directly from H&E-stained histology sections—a task that traditionally requires specialized molecular assays [4]. Across 19 biomarker prediction tasks, Virchow2 and CONCH achieved the highest mean AUROCs of 0.73, significantly outperforming traditional approaches [4]. This capability to infer molecular status from morphology has profound implications for drug development, potentially enabling retrospective studies on archival tissue samples and enriching clinical trial populations based on biomarker status without additional testing.

The complementary strengths of different foundation model architectures emerged as a notable finding. Vision-language models like CONCH, trained with paired image-text data, excelled at capturing semantically meaningful features that align with pathological descriptors [4] [5]. In contrast, vision-only models like Virchow2 demonstrated superior performance in certain tissue-specific classifications. Ensemble approaches that combined predictions from complementary models achieved state-of-the-art performance, outperforming individual models in 55% of tasks [4].

Architectural and Representational Analysis

Representational Similarity Across Models

Representational similarity analysis (RSA) of six computational pathology foundation models revealed distinct clustering patterns based on training methodology [5]. Models employing the same training paradigm did not necessarily learn similar representations—UNI2 and Virchow2, both vision-only foundation models, exhibited the most distinct representational structures despite their architectural similarities [5]. This finding suggests that training data characteristics and specific learning objectives may exert greater influence on learned representations than the training algorithm alone.

The analysis further revealed that all foundation models showed high slide-dependence in their representations, indicating sensitivity to technical artifacts such as staining variations and scanner specifications [5]. However, application of stain normalization techniques reduced this slide-dependence by 5.5% (CONCH) to 20.5% (PLIP), highlighting the potential for preprocessing standardization to improve model robustness [5]. Vision-language models demonstrated more compact representations (lower intrinsic dimensionality) compared to the distributed representations of vision-only models, potentially contributing to their superior data efficiency [5].

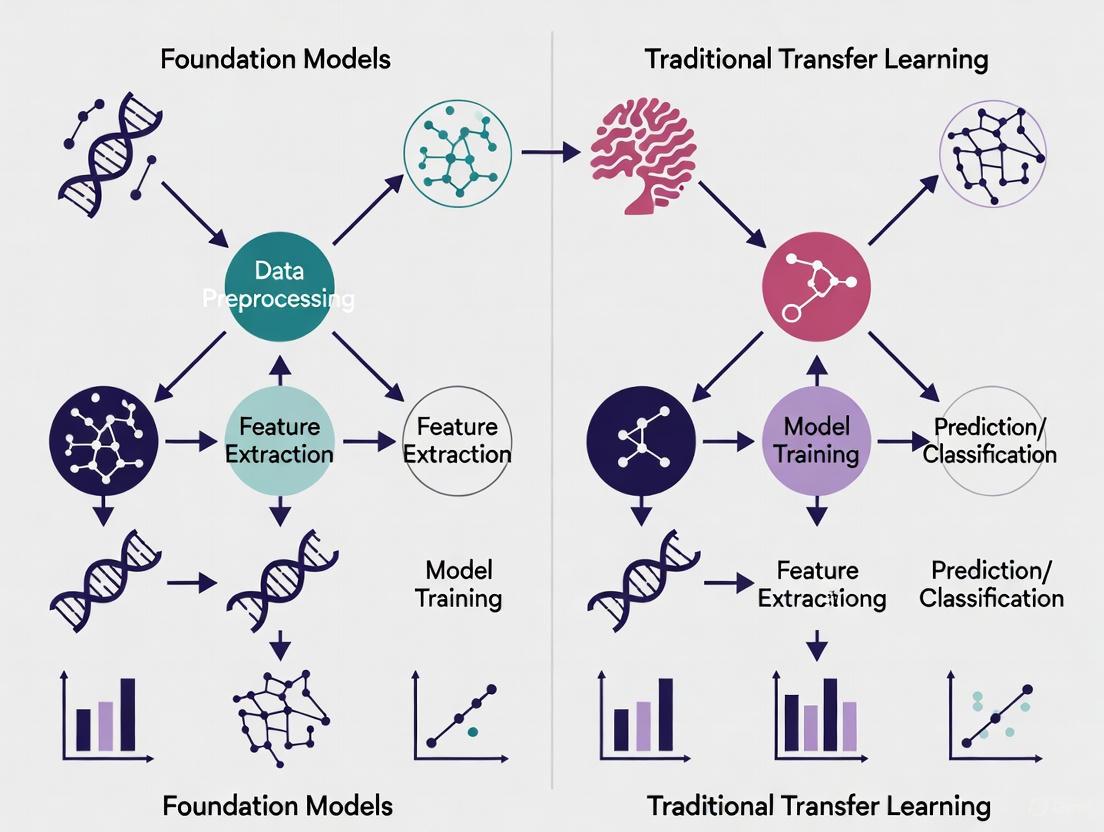

Figure 2: Architectural Paradigms in Computational Pathology. Traditional transfer learning and foundation models employ fundamentally different approaches, resulting in significant differences in data efficiency and generalization capability.

Research Reagent Solutions for Implementation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Computational Pathology Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Model | Primary Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vision-Language Foundation Models | CONCH | Joint image-text representation learning for histopathology | GitHub Repository |

| Vision-Only Foundation Models | Virchow2 | Large-scale visual representation learning from 3.1M WSIs | MSKCC Access Portal |

| Vision-Only Foundation Models | UNI2 | General-purpose feature extraction from H&E and IHC images | Hugging Face Hub |

| Benchmarking Frameworks | Multi-task benchmark suite | Standardized evaluation across 31 clinical tasks | Custom implementation per [4] |

| Slide Processing Tools | OpenSlide | Whole-slide image reading and processing | Python Library |

| Representation Analysis | RSA Toolbox | Representational similarity analysis for model comparisons | Python Package |

The experimental evidence consistently demonstrates that foundation models overcome the fundamental limitations of traditional transfer learning approaches in computational pathology. Through self-supervised pre-training on diverse histopathology datasets, foundation models achieve superior performance while substantially reducing the data requirements for downstream task adaptation [3] [4]. The emergence of models excelling across morphological assessment, biomarker prediction, and prognostic forecasting signals a shift toward general-purpose pathological intelligence that can accelerate drug development and personalized therapeutic strategies.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings suggest a strategic imperative to transition from task-specific models to foundation model-based approaches. The complementary strengths of vision-language and vision-only architectures further indicate that ensemble methods may offer the most robust solution for critical clinical applications [4]. As the field advances, the focus will likely shift from model development to optimal deployment strategies, including domain adaptation techniques to address site-specific variations and integration with multimodal data streams to create comprehensive diagnostic systems.

What Makes a Model 'Foundational'? Core Principles and Definitions

Foundation models represent a fundamental shift in artificial intelligence, moving from specialized, single-task models to versatile, general-purpose systems. The term "foundation model" was formally coined in 2021 by Stanford's Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence to mean "any model that is trained on broad data (generally using self-supervision at scale) that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks" [6] [7]. Unlike traditional AI models designed for specific applications, foundation models learn general patterns and representations from massive datasets, enabling adaptation to numerous tasks through fine-tuning or prompting without starting from scratch [6] [7].

In computational pathology, this paradigm shift is particularly transformative. While traditional models might be trained specifically for tumor classification or segmentation, pathology foundation models like TITAN (Transformer-based pathology Image and Text Alignment Network) are pretrained on hundreds of thousands of whole-slide images across multiple organs and can subsequently be adapted to diverse clinical challenges including cancer subtyping, biomarker prediction, and prognosis analysis [8]. This guide examines the core principles defining foundation models and provides experimental comparisons with traditional transfer learning approaches specifically for pathology research applications.

Core Principles of Foundation Models

Scale: Data, Model Size, and Compute

Foundation models are characterized by unprecedented scale across three dimensions: training data volume, model parameter count, and computational requirements. TITAN, for instance, was pretrained using 335,645 whole-slide images and 182,862 medical reports, with additional fine-tuning on 423,122 synthetic captions [8]. This massive scale enables the model to learn comprehensive representations of histopathological patterns across diverse tissue types and disease states. The 2025 State of Foundation Model Training Report confirms this trend, noting that models and training datasets continue to grow larger, generally leading to improved task performance [9].

Self-Supervised Learning on Broad Data

Rather than relying on manually labeled datasets, foundation models predominantly use self-supervised learning objectives that create training signals from the data itself [6] [7]. In pathology, this might involve masked image modeling where parts of a whole-slide image are hidden and the model must predict the missing portions based on context [8]. This approach allows models to learn from vast quantities of unlabeled histopathology data, capturing fundamental patterns of tissue morphology and organization without human annotation bottlenecks.

Versatility and Adaptability

A defining characteristic of foundation models is their adaptability to diverse downstream tasks. For example, Apple's Foundation Models framework enables developers to leverage a single on-device model for applications ranging from generating workout summaries in fitness apps to providing scientific explanations in educational tools [10]. In pathology, the same TITAN model can be adapted for cancer subtyping, biomarker prediction, outcome prognosis, and slide retrieval tasks without architectural changes [8].

Emergent Capabilities

Through scale and broad pretraining, foundation models often exhibit emergent capabilities not explicitly programmed during training. These include in-context learning (adapting to new tasks through examples provided in prompts), cross-modal reasoning (connecting information across different data types), and compositional generalization [6]. The TITAN model demonstrates this through its ability to perform cross-modal retrieval between histology slides and clinical reports, enabling powerful search capabilities across pathology databases [8].

Foundation Models vs. Traditional Transfer Learning in Computational Pathology

Conceptual Framework Comparison

The table below contrasts the fundamental approaches of foundation models versus traditional transfer learning in computational pathology research:

| Aspect | Foundation Models | Traditional Transfer Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Training Data | Massive, diverse datasets (e.g., 300K+ WSIs across 20 organs) [8] | Limited, task-specific datasets |

| Learning Paradigm | Self-supervised pretraining followed by adaptation [8] [6] | Supervised fine-tuning of pre-trained models [11] |

| Architecture | Transformer-based with specialized adaptations for gigapixel WSIs [8] | Often CNN-based with standard architectures [11] |

| Scope | General-purpose slide representations adaptable to multiple tasks [8] | Specialized for single applications |

| Data Efficiency | Strong performance in low-data regimes through pretrained representations [8] | Requires substantial task-specific data for effective transfer [11] |

| Multimodal Capability | Native handling of images, text, and other data types [8] | Typically unimodal with late fusion |

Experimental Performance Comparison

Recent studies directly compare foundation models against traditional transfer learning approaches in pathology applications. The following table summarizes key experimental findings:

| Experiment | Foundation Model Approach | Traditional Transfer Learning | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral HSI Classification [11] | N/A | End-to-end fine-tuning of RGB-pretrained models | Best performance: 85-92% accuracy with optimal hyperparameters |

| Rare Cancer Retrieval [8] | TITAN zero-shot retrieval | Specialized retrieval models | TITAN superior in limited-data scenarios |

| Cancer Prognosis [12] | Path-PKT knowledge transfer | Cancer-specific model development | Positive transfer between related cancers; negative transfer between dissimilar cancers |

| Slide-Level Classification [8] | TITAN with linear probing | ROI-based foundation models | TITAN outperformed across multiple cancer types |

| Interatomic Potentials [13] | MACE-freeze transfer learning | From-scratch training | Transfer learning achieved similar accuracy with 10-20% of training data |

Methodological Details

Foundation Model Training Protocol (TITAN)

The TITAN model employs a three-stage training paradigm [8]:

- Vision-only pretraining: Self-supervised learning on 335,645 WSIs using iBOT framework (masked image modeling and knowledge distillation)

- ROI-level alignment: Contrastive learning with 423,122 synthetic fine-grained region captions

- Slide-level alignment: Multimodal alignment with 182,862 pathology reports

This protocol uses a Vision Transformer architecture processing features from 512×512 patches extracted at 20× magnification, with specialized attention mechanisms (ALiBi) for handling long sequences of patch features [8].

Traditional Transfer Learning Protocol (Hyperspectral Imaging)

For adapting RGB-pretrained models to hyperspectral data, researchers implemented [11]:

- Input layer modification: Replaced first layer to accept 87 spectral channels instead of 3 RGB channels

- Weight initialization: Spectral channels weighted based on contribution to RGB channels

- Hyperparameter optimization: Bayesian search over learning rate (1e-7 to 0.1), weight decay (1e-4 to 0.5), and AdamW betas

- Training strategies comparison: End-to-end fine-tuning vs. embedding-only training vs. embedding-first training

The optimal configuration used low learning rates and high weight decays, with end-to-end fine-tuning outperforming other approaches [11].

Visualizing Foundation Model Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the core architecture and workflow of a multimodal pathology foundation model like TITAN:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key computational tools and resources used in developing and evaluating pathology foundation models:

| Research Reagent | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-Slide Image Datasets | Large-scale pretraining data | Mass-340K (335,645 WSIs, 20 organs) [8] |

| Synthetic Captions | Vision-language alignment | PathChat-generated ROI descriptions (423K pairs) [8] |

| Patch Encoders | Feature extraction from image regions | CONCHv1.5 (768-dimensional features) [8] |

| Transformer Architectures | Context modeling across patches | ViT with ALiBi attention [8] |

| Self-Supervised Objectives | Pretraining without manual labels | iBOT (masked image modeling + distillation) [8] |

| Cross-Modal Alignment | Connecting visual and textual representations | Contrastive learning with report-slide pairs [8] |

| Hyperparameter Optimization | Model performance tuning | Bayesian search (learning rate, weight decay) [11] |

| Transfer Learning Protocols | Domain adaptation | Frozen weight transfer (MACE-freeze) [13] |

Foundation models represent a fundamental architectural and methodological shift from traditional transfer learning approaches in computational pathology. While traditional methods excel in specialized applications with sufficient data, foundation models offer superior versatility, data efficiency, and emergent capabilities—particularly valuable for rare diseases and multimodal applications [8] [12].

The experimental evidence demonstrates that foundation models like TITAN achieve state-of-the-art performance across diverse pathology tasks while reducing dependency on large, labeled datasets [8]. However, traditional transfer learning remains effective when adapting models between similar domains or with sufficient target data [11]. As the field evolves, the integration of foundation models with specialized transfer techniques—such as frozen weight transfer [13] and prognostic knowledge routing [12]—promises to further enhance their utility for pathological research and clinical applications.

For research teams, the decision between developing foundation models versus applying traditional transfer learning involves trade-offs in computational resources, data availability, and application scope. Foundation models require substantial upfront investment but offer greater long-term flexibility, while traditional approaches provide more immediate solutions for well-defined problems with established methodologies.

The field of computational pathology is undergoing a significant architectural transformation, moving from long-dominant Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) toward emerging Vision Transformer (ViT) models. This evolution is particularly evident in the context of a broader methodological shift: the rise of foundation models pretrained on massive, diverse datasets versus traditional transfer learning approaches that fine-tune networks pretrained on general image collections like ImageNet. Foundation models, pretrained through self-supervised learning on millions of histopathology images, represent a paradigm shift from traditional transfer learning, which typically relies on supervised pretraining on natural images followed by domain-specific fine-tuning. Understanding the relative strengths, limitations, and optimal application domains for each architectural approach has become crucial for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to leverage artificial intelligence for pathological image analysis. This guide provides an objective comparison of these architectures, supported by recent experimental data and detailed methodological insights to inform model selection for computational pathology applications.

Architectural Fundamentals: Core Design Philosophies

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): Local Feature Specialists

CNNs process visual data through a hierarchy of convolutional filters that scan local regions of images, progressively building up from simple edges to complex patterns. This architecture incorporates strong inductive biases for translation invariance and locality, meaning they assume that nearby pixels are more related than distant ones. This design mirrors human visual perception of focusing on local details before assembling the bigger picture. In pathology imaging, CNNs excel at identifying cellular-level features, nuclear morphology, and local tissue patterns through their convolutional operations [14]. Their architectural strength lies in parameter sharing through convolutional kernels, which makes them computationally efficient and well-suited for analyzing the repetitive local structures commonly found in histopathological images.

Popular CNN architectures used in pathology include ResNet, EfficientNet, DenseNet, and VGG-16, which have demonstrated strong performance in various diagnostic tasks. For instance, VGG-16 has been successfully applied to classify power Doppler ultrasound images of rheumatoid arthritis joints using transfer learning [15]. The efficiency of CNNs stems from their convolutional layers, which extract hierarchical features while maintaining spatial relationships, and pooling layers, which progressively reduce feature map dimensions to increase receptive field size without exploding computational complexity.

Vision Transformers (ViTs): Global Context Integrators

Vision Transformers process images fundamentally differently by dividing them into patches and treating these patches as a sequence of tokens, similar to how Transformers process words in natural language. Through self-attention mechanisms, ViTs learn relationships between any two patches regardless of their spatial separation, enabling them to capture global context and long-range dependencies across entire whole-slide images (WSIs) [14]. This global perspective is particularly valuable in pathology for understanding tissue architecture, tumor-stroma interactions, and spatial relationships between distant histological structures.

Unlike CNNs, ViTs have minimal built-in inductive biases about images and instead learn relevant visual patterns directly from data. This flexibility allows them to develop more sophisticated representations but comes at the cost of requiring substantial training data to generalize effectively. The self-attention mechanism computes weighted sums of all input patches, with weights determined by compatibility between patches, allowing the model to focus on clinically relevant regions while suppressing irrelevant information. For example, ViT-based models have demonstrated superior capability in classifying squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) margins on low-quality histopathological images, achieving 0.928 ± 0.027 accuracy compared to 0.86 ± 0.049 for the highest-performing CNN model (InceptionV3) [16].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Analysis Across Pathology Tasks

Table 1: Performance comparison of CNN vs. ViT architectures across multiple pathology applications

| Pathology Task | Dataset | Best CNN Model (Performance) | Best ViT Model (Performance) | Performance Delta |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCC Margin Classification | Low-quality histopathological images | InceptionV3 (Accuracy: 0.860 ± 0.049; AUC: 0.837 ± 0.029) | Custom ViT (Accuracy: 0.928 ± 0.027; AUC: 0.927 ± 0.028) | +7.8% Accuracy, +9.0% AUC [16] |

| Breast Cancer Lymph Node Micrometastasis | BLCN-MiD & Camelyon (4× magnification) | ResNet34 | rMetaTrans (Optimized ViT) | +3.67-6.96% across metrics [17] |

| Dental Image Analysis | 21-study systematic review | Various CNNs | ViT-based models | ViT superior in 58% of studies [18] |

| Colorectal Cancer Classification | EBHI dataset (200×) | Multiple CNNs | Feature fusion with self-attention | 99.68% accuracy [19] |

| Melanoma Diagnosis | ISIC datasets | Ensemble CNNs | CNN-ViT ensemble | 95.25% accuracy [20] |

Table 2: Data efficiency and computational requirements comparison

| Characteristic | CNNs | Vision Transformers |

|---|---|---|

| Data Efficiency | Perform well with limited annotated data [14] | Require large-scale data for effective training [14] |

| Computational Demand | Lower computational requirements [14] | Higher computational complexity during training [17] |

| Training Speed | Faster training cycles | Longer training times [18] |

| Inference Speed | Optimized for deployment, suitable for edge devices [14] | Can be optimized through architectural modifications [17] |

| Pretraining Requirements | ImageNet transfer learning effective | Benefit from domain-specific pretraining [8] |

Foundation Models vs. Traditional Transfer Learning: Methodological Divide

The architectural evolution from CNNs to ViTs coincides with a methodological shift from traditional transfer learning to foundation models. Traditional transfer learning typically involves pretraining a model on a large-scale natural image dataset (e.g., ImageNet), then fine-tuning the weights on a smaller target pathology dataset. This approach leverages generalized visual features but suffers from domain shift when natural images differ substantially from histopathological images [19]. For example, a study on colorectal cancer classification applied domain-specific transfer learning using CNNs pretrained on intermediate histopathological datasets rather than natural images, enhancing feature relevance for the target domain [19].

In contrast, pathology foundation models are pretrained directly on massive histopathology datasets using self-supervised learning, capturing domain-specific morphological patterns. A prominent example is TITAN (Transformer-based pathology Image and Text Alignment Network), a multimodal whole-slide foundation model pretrained on 335,645 whole-slide images via visual self-supervised learning and vision-language alignment [8]. This approach learns general-purpose slide representations that transfer effectively across diverse clinical tasks without task-specific fine-tuning. Foundation models address the data scarcity challenge in pathology by learning from vast unlabeled datasets, then applying this knowledge to downstream tasks with minimal labeled examples.

Experimental evidence demonstrates that foundation models significantly outperform traditional transfer learning approaches, particularly in low-data regimes and rare disease contexts. Virchow2, a pathology foundation model, delivered the highest performance across multiple tasks from TCGA, CPTAC, and external benchmarks compared to both general vision models and traditional transfer learning approaches [21]. Similarly, TITAN outperformed supervised baselines and existing slide foundation models in cancer subtyping, biomarker prediction, outcome prognosis, and slide retrieval tasks [8].

Diagram 1: Workflow comparison between traditional transfer learning and foundation model approaches in computational pathology. The foundation model paradigm leverages self-supervised pretraining on large-scale pathology-specific datasets, enabling zero-shot application or minimal fine-tuning, while traditional approaches require extensive domain adaptation from natural images.

Experimental Protocols: Methodological Insights from Key Studies

ViT for Low-Quality Histopathological Images

Objective: To evaluate Vision Transformers for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) margin classification on low-quality histopathological images from resource-limited settings [16].

Dataset: Comprised histopathological slides from 50 patients with SCC (17 well-differentiated, 15 moderately differentiated, 18 invasive SCC) from Jimma University Medical Center in Ethiopia, including 345 normal tissue images and 483 tumor images designated as margin positive.

Preprocessing: Original high-resolution images (2048 × 1536 pixels) were resized to 224 × 224 pixels. Data augmentation techniques included flipping, scaling, and rotation to increase dataset diversity and prevent overfitting.

Model Architecture: Custom ViT architecture employing transfer learning approach with additional flattening, batch normalization, and dense layers. Implemented five-fold cross-validation for robust performance estimation.

Evaluation Metrics: Primary metrics included accuracy, area under the curve (AUC), with ablation studies exploring architectural configuration effects.

MetaTrans for Breast Cancer Lymph Node Micrometastasis

Objective: To develop MetaTrans, a novel network combining meta-learning with Transformer blocks for detecting lymph node micro-metastases in breast cancer under limited data conditions [17].

Dataset: Constructed 34-category WSI dataset (MT-MCD) for meta-training, including multi-center small metastasis datasets with both paraffin and frozen sections.

Architecture: Integrated meta-learning with Transformer blocks to address limitations of pure Transformers in capturing fine-grained local details of micro-lesions. Employed tissue-recognition model for regions of interest at low magnification (Model4x) and cell-recognition model for high magnification (Model10x).

Training Strategy: Inspired by pathologists' diagnostic practices, the process captures a field of view at 4× magnification, divides it into 256 × 256 patches, processes them with MetaTrans to generate probability distribution and attention maps within 5 seconds.

Evaluation: Comprehensive cross-dataset and cross-disease validation on BLCN-MiD and Camelyon datasets, comparing against CNN baselines (ResNet18, ResNet34, ResNet50) and vanilla ViT architectures (ViTSmall, ViTBase).

TITAN Foundation Model Pretraining

Objective: To develop TITAN, a multimodal whole-slide foundation model for general-purpose slide representation learning in histopathology [8].

Pretraining Data: Mass-340K dataset comprising 335,645 WSIs across 20 organ types with diverse stains, tissue types, and scanner types, plus 182,862 medical reports.

Three-Stage Pretraining:

- Vision-only unimodal pretraining: Using iBOT framework on region crops (8,192 × 8,192 pixels at 20× magnification)

- ROI-level cross-modal alignment: With 423k pairs of ROIs and synthetic captions generated using PathChat

- WSI-level cross-modal alignment: With 183k pairs of WSIs and clinical reports

Architecture Innovations: Extended attention with linear bias (ALiBi) to 2D for long-context extrapolation; constructed input embedding space by dividing each WSI into non-overlapping patches of 512 × 512 pixels at 20× magnification; used CONCHv1.5 for patch feature extraction.

Evaluation Tasks: Diverse clinical applications including cancer subtyping, biomarker prediction, outcome prognosis, slide retrieval, rare cancer retrieval, cross-modal retrieval, and pathology report generation in zero-shot settings.

Diagram 2: Complementary strengths of CNNs and Vision Transformers in computational pathology, showing how emerging hybrid architectures integrate benefits from both approaches for enhanced clinical applications.

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational resources for pathology AI research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | Camelyon (lymph node metastases), TCGA (multi-cancer), CPTAC (proteogenomic), NCT-CRC-HE-100K (colorectal cancer) | Benchmarking, pretraining, and validation of models across different cancer types and tasks [17] [21] |

| Pretrained Models | CONCH (histopathology patch encoder), Virchow2 (pathology foundation model), TITAN (whole-slide foundation model) | Transfer learning, feature extraction, and baseline comparisons for development [8] [21] |

| Evaluation Frameworks | Five-fold cross-validation, external validation datasets, ablation studies | Robust performance assessment and generalization testing [16] [17] |

| Computational Infrastructure | High-memory GPUs (for processing whole-slide images), distributed training systems | Handling computational demands of transformer architectures and large whole-slide images [8] |

| Data Augmentation Tools | Flipping, rotation, scaling, stain normalization, synthetic data generation | Addressing data scarcity and improving model generalization [16] [19] |

The evolution from CNNs to Vision Transformers in computational pathology represents more than a mere architectural shift—it embodies a fundamental transformation in how artificial intelligence models perceive and interpret histopathological images. CNNs remain highly valuable for resource-constrained environments, edge deployments, and tasks where local feature extraction is paramount, while ViTs excel in whole-slide analysis, global context modeling, and foundation model applications. The emerging consensus favors hybrid approaches that integrate the complementary strengths of both architectures, such as ConvNeXt, Swin Transformers, and MetaTrans [14] [17].

The parallel transition from traditional transfer learning to pathology-specific foundation models addresses critical limitations in domain adaptation and data efficiency. Foundation models like TITAN and Virchow2 demonstrate that self-supervised pretraining on massive histopathology datasets produces more versatile and generalizable representations than ImageNet-based transfer learning [8] [21]. For researchers and drug development professionals, strategic model selection should consider not only architectural differences but also the pretraining paradigm, with foundation models increasingly becoming the preferred approach for their superior performance in few-shot and zero-shot settings.

As computational pathology continues to evolve, the integration of multimodal data (imaging, genomics, clinical reports) through transformer-based architectures represents the most promising direction for developing comprehensive AI diagnostic systems that can meaningfully assist pathologists and accelerate drug development workflows.

The field of computational pathology is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by a quantum leap in the scale of training data. The transition from models trained on thousands of Whole-Slide Images (WSIs) to those trained on hundreds of thousands or even millions represents a pivotal shift from task-specific algorithms toward general-purpose foundation models. This evolution mirrors the trajectory seen in natural language processing, where large-scale pretraining has unlocked unprecedented capabilities. In pathology, foundation models are deep neural networks pretrained on massive collections of histology image fragments without specific human labels, learning to understand cellular patterns, tissue architecture, and staining variations across diverse organs and diseases [22]. Unlike traditional transfer learning—which often adapts models pretrained on natural images to specific medical tasks with limited data—foundation models are pretrained directly on vast histopathology datasets, capturing the intrinsic morphological diversity of human tissue at scale [22]. This paradigm shift enables models to serve as versatile visual backbones that can be efficiently adapted to numerous clinical and research applications with minimal fine-tuning.

Quantitative Comparison: Traditional vs. Foundation Model Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Data Scale and Model Architectures

| Model / Approach | Training Data Scale | Model Architecture | Pretraining Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Transfer Learning | Thousands to tens of thousands of WSIs [23] [24] | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [24] | Supervised learning on specific tasks [24] |

| TITAN | 335,645 WSIs across 20 organ types [8] | Vision Transformer (ViT) [8] | Self-supervised learning (iBOT) & multimodal alignment [8] |

| Prov-GigaPath | 171,189 WSIs (1.3 billion image patches) [22] | GigaPath (using LongNet dilated attention) [22] | Self-supervised learning on gigapixel images [22] |

| UNI | 100,000+ WSIs (100 million patches) [22] | Vision Transformer [22] | Self-supervised learning for universal representation [22] |

Performance Comparison Across Clinical Tasks

Table 2: Performance Metrics on Diagnostic and Prognostic Tasks

| Model / Approach | Cancer Subtyping Accuracy | Rare Disease Retrieval | Zero-shot Classification | Biomarker Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional CNN (Weakly Supervised) | 0.908 micro-accuracy (image-level) [24] | Not reported | Not applicable | Not reported |

| TITAN | Outperforms ROI and slide foundation models across multiple subtyping tasks [8] | Superior performance in rare cancer retrieval [8] | Enables zero-shot classification via vision-language alignment [8] | Outperforms supervised baselines [8] |

| Prov-GigaPath | State-of-the-art in 25/26 clinical tasks, including 9 cancer types [22] | Not specifically reported | Enables zero-shot classification from clinical descriptions [22] | Predicts genetic alterations (e.g., MSI status) from H&E [22] |

| Virchow | AUC 0.95 for tumor detection across 9 common and 7 rare cancers [22] | Demonstrates impressive generalization for rare cancers [22] | Not specifically reported | Outperforms organ-specific clinical models with fewer labeled data [22] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Foundation Model Pretraining Workflow

Foundation Model Pretraining Pathway

The TITAN model exemplifies the sophisticated methodologies employed in modern pathology foundation models. The pipeline begins with Whole-Slide Images (WSIs) being processed through a patch embedding layer, typically using established patch encoders like CONCH, to extract meaningful feature representations [8]. These features are spatially arranged in a two-dimensional grid that preserves the architectural context of the tissue [8]. The pretraining proceeds through three progressive stages: (1) vision-only self-supervised learning using the iBOT framework that employs knowledge distillation and masked image modeling; (2) cross-modal alignment with fine-grained morphological descriptions generated from 423,000 synthetic captions; and (3) slide-level alignment with 183,000 pathology reports [8]. This multistage approach enables the model to learn both visual semantics and their correspondence with clinical language, unlocking capabilities in zero-shot reasoning and cross-modal retrieval.

Traditional Weakly-Supervised Approach

Traditional Weakly-Supervised Learning Pathway

Traditional approaches rely on weakly-supervised frameworks that automatically extract labels from pathology reports to train convolutional neural networks. The Semantic Knowledge Extractor Tool (SKET) employs an unsupervised hybrid approach combining rule-based systems with pretrained machine learning models to derive semantically meaningful concepts from free-text diagnostic reports [24]. These automatically generated labels then train a Multiple Instance Learning CNN framework that processes individual patches from WSIs and aggregates predictions using attention pooling to produce slide-level classifications [24]. While this approach eliminates the need for manual annotations and leverages existing clinical data, it remains constrained by its focus on specific tasks and limited ability to generalize beyond its training distribution.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-Slide Scanners | Leica Aperio AT2/GT450, Hamamatsu NanoZoomer S360, Philips UFS, 3DHistech Pannoramic 1000 [25] | Digitize glass slides into high-resolution whole-slide images for computational analysis |

| Patch Encoders | CONCH, CONCHv1.5 [8] | Encode histopathology regions-of-interest into feature representations for slide-level processing |

| Computational Frameworks | Vision Transformers (ViT), GigaPath with LongNet dilated attention [22] | Process long sequences of patch embeddings from gigapixel WSIs while capturing global context |

| Self-Supervised Learning Methods | iBOT, masked autoencoders (MAE), DINO contrastive learning [8] [22] | Pretrain models without human annotations by solving pretext tasks like masked image modeling |

| Multimodal Datasets | Pathology reports, synthetic captions, transcriptomics data [8] [22] | Provide complementary supervisory signals for vision-language alignment and multimodal reasoning |

| Quality Control Tools | Focus assessment, artifact detection, missing tissue identification [25] [26] | Ensure digital slide quality and identify scanning errors that could compromise model performance |

Discussion: Implications for Research and Drug Development

The leap from thousands to millions of whole-slide images represents more than a quantitative scaling—it marks a qualitative transformation in how computational pathology approaches pattern recognition and diagnostic reasoning. Foundation models pretrained at this scale demonstrate emergent capabilities, including zero-shot classification, rare disease retrieval, and molecular pattern inference directly from H&E stains [8] [22]. For research and drug development, these advances offer compelling opportunities: identifying subtle morphological biomarkers invisible to the human eye, predicting treatment response through integrated analysis of histology with clinical and genomic data, and accelerating drug discovery by revealing novel genotype-phenotype correlations [22].

The integration of multimodal data streams represents perhaps the most promising frontier. Models like THREADS now align histological images with RNA-seq expression profiles and DNA data, creating bridges between tissue morphology and molecular signatures [22]. Similarly, approaches like MIFAPS integrate MRI, whole-slide images, and clinical data to predict pathological complete response in breast cancer [22]. For pharmaceutical researchers, these capabilities enable more precise patient stratification, biomarker discovery, and understanding of drug mechanisms across tissue contexts.

However, this paradigm shift also introduces new challenges. The computational resources required for training foundation models are substantial, often requiring tens of thousands of GPU hours [22]. Data standardization remains critical, as variations in staining protocols, scanner models, and tissue preparation can significantly impact model performance [23] [25]. Importantly, the transition to foundation models does not eliminate the need for domain expertise—rather, it repositions pathologists as interpreters of model outputs and validators of clinical relevance [22].

The scaling of training data from thousands to millions of whole-slide images has catalyzed a fundamental shift from task-specific models to general-purpose foundation models in computational pathology. This transition has demonstrated unequivocal benefits in diagnostic accuracy, generalization to rare conditions, and multimodal reasoning capabilities. While traditional transfer learning approaches remain viable for focused applications with limited data, foundation models offer a more versatile and powerful paradigm for organizations with access to large-scale data and computational resources. As these models continue to evolve, they promise to deepen our understanding of disease biology and accelerate the development of targeted therapies through their ability to discern subtle morphological patterns and their correlations with molecular features and clinical outcomes.

The development of computational pathology tools has been historically constrained by the limited availability of large-scale annotated histopathology datasets. Traditional transfer learning from natural image domains (e.g., ImageNet) presents significant limitations due to domain shift issues, as histopathology images exhibit fundamentally different characteristics including complex tissue structures, specific staining patterns, and substantially higher resolution. Self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a transformative paradigm that leverages inherent patterns within unannotated data to learn robust, transferable representations, effectively addressing annotation bottlenecks in medical imaging [27] [28].

Within SSL, two predominant frameworks have demonstrated remarkable success in histopathology applications: contrastive learning and masked image modeling. These approaches differ fundamentally in their learning objectives, architectural requirements, and performance characteristics across various computational pathology tasks. This comparative analysis examines their methodological principles, experimental performance, and implementation considerations within the broader context of foundation model development for histopathology, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for selecting appropriate paradigms for specific clinical and research applications.

Methodological Foundations

Contrastive Learning Frameworks

Contrastive learning operates on the principle of discriminative representation learning by maximizing agreement between differently augmented views of the same image while pushing apart representations from different images. In histopathology, this approach has been extensively adapted to handle the unique characteristics of whole-slide images (WSIs), including their gigapixel sizes and hierarchical tissue structures [29] [30].

The core objective function typically follows the Noise Contrastive Estimation (InfoNCE) framework, which aims to identify positive pairs (different views of the same histopathology patch) among negative samples (views from different patches). Key implementations in histopathology include:

- SimCLR (Simplified Contrastive Learning of Representations): Employed on collections of 57 histopathology datasets without labels, demonstrating that combining multi-organ datasets with varied staining and resolution properties improves learned feature quality [29].

- MoCo v2 (Momentum Contrast v2): Used for in-domain pretraining on colon adenocarcinoma cohorts from TCGA, significantly outperforming ImageNet pretraining on metastasis detection tasks [28].

- DINO (self-DIstillation with NO labels): Leverages vision transformers (ViTs) through self-distillation without labels, using similarity matching between global and local crop embeddings via cross-entropy loss [28].

Masked Image Modeling Frameworks

Masked image modeling (MIM) draws inspiration from masked language modeling in natural language processing (e.g., BERT), where the model learns to predict masked portions of the input data based on contextual information. For histopathology images, this approach forces the model to develop a comprehensive understanding of tissue microstructure and spatial relationships [31] [28].

The iBOT framework (image BERT pre-training with Online Tokenizer) has emerged as a particularly effective MIM implementation for histopathology, combining masked patch modeling with online tokenization. Key characteristics include:

- Dual self-distillation objectives: Simultaneously learns both low-level histomorphological details (through masked patch reconstruction) and high-level visual semantics (through class token distillation) [31] [28].

- Online tokenizer: Dynamically generates training targets through a momentum teacher network, avoiding the need for predefined visual vocabularies.

- Pan-cancer representation learning: Effectively captures morphological patterns across diverse cancer types when trained on large-scale datasets (e.g., 40+ million images from 16 cancer types) [31].

Table 1: Core Methodological Differences Between SSL Paradigms

| Aspect | Contrastive Learning | Masked Image Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Learning Objective | Discriminate between similar and dissimilar image pairs | Reconstruct masked portions of input images |

| Primary Signal | Instance discrimination | Contextual prediction |

| Data Augmentation | Heavy reliance on carefully designed augmentations | Less dependent on complex augmentations |

| Architecture | Compatible with CNNs and ViTs | Primarily optimized for Vision Transformers |

| Representation Level | Emphasis on global semantics | Balances local texture and global structure |

Experimental Performance Comparison

Benchmarking Studies and Direct Comparisons

Comprehensive evaluations across diverse histopathology tasks consistently demonstrate the advantages of in-domain SSL pretraining over traditional ImageNet transfer learning. However, significant performance differences exist between contrastive and MIM approaches depending on task characteristics and data regimes.

The iBOT framework, as a leading MIM implementation, has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance across 17 downstream tasks spanning seven cancer indications, including weakly-supervised WSI classification and patch-level tasks. Specifically, iBOT pretrained on pan-cancer datasets outperformed both ImageNet pretraining and MoCo v2 (a contrastive approach) on tasks including microsatellite instability (MSI) prediction, homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) classification, cancer subtyping, and overall survival prediction [28].

Notably, MIM approaches exhibit particularly strong performance in low-data regimes, maintaining robust representation quality even with limited fine-tuning examples. This property is especially valuable in histopathology, where annotated datasets for rare cancers or molecular subtypes are often small [28]. Contrastive methods, while generally effective, show greater performance degradation when pretraining datasets exhibit significant class imbalance - a common scenario in real-world histopathology collections [27].

Scaling Properties and Data Efficiency

The development of foundation models in histopathology depends critically on understanding how performance scales with model size, data volume, and data diversity. Evidence suggests that MIM approaches exhibit favorable scaling properties compared to contrastive methods:

- Model Scaling: Vision Transformers pretrained with iBOT demonstrate consistent performance improvements as model size increases from 22 million to 307 million parameters, particularly when coupled with larger pretraining datasets [28].

- Data Scaling: MIM performance improves monotonically with increased pretraining data size and diversity. iBOT pretrained on 43 million histology images from 16 cancer types outperformed versions trained on smaller, organ-specific cohorts [31].

- Multimodal Extension: MIM representations serve as effective foundations for vision-language models like TITAN (Transformer-based pathology Image and Text Alignment Network), enabling zero-shot classification and cross-modal retrieval without task-specific fine-tuning [8].

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Histopathology Tasks

| Task Category | Contrastive Learning (SimCLR/MoCo) | Masked Image Modeling (iBOT) | Evaluation Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slide-Level Classification | 28% improvement over ImageNet [29] | Outperforms MoCo v2 by 3-8% [28] | F1 Score / AUROC |

| Patch-Level Classification | Comparable to ImageNet pretraining [29] | Significant improvements on nuclear segmentation and classification | Accuracy |

| Molecular Prediction | Moderate performance on MSI/HRD prediction | State-of-the-art on pan-cancer mutation prediction [28] | AUROC |

| Survival Prediction | Limited demonstrations | Strong performance in multi-cancer evaluation [28] | C-Index |

| Few-Shot Learning | Moderate transferability | Excellent performance with limited labels [28] | Accuracy |

Implementation Considerations

Technical Requirements and Workflows

Implementing SSL frameworks in histopathology requires specialized computational infrastructure and data processing pipelines. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for MIM-based foundation model development:

Data Preprocessing Requirements:

- Patch Extraction: WSIs are divided into smaller patches (typically 256×256 or 512×512 pixels at 20× magnification) [8] [28].

- Color Normalization: Addresses staining variations across institutions using methods like Macenko or Vahadane normalization.

- Feature Grid Construction: For slide-level modeling, patches are arranged in 2D spatial grids preserving tissue topology [8].

Computational Infrastructure:

- Hardware: Multiple high-end GPUs (e.g., A100 or H100) with substantial VRAM (≥80GB).

- Training Time: Ranges from days to weeks depending on dataset size (millions to hundreds of millions of patches).

- Storage: Large-scale distributed storage systems capable of handling petabyte-scale whole-slide image repositories.

Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for SSL in Histopathology

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Pretrained Models | iBOT (ViT-Base/Large), UNI, CTransPath, CONCH | Foundation models for transfer learning and feature extraction [31] [8] [32] |

| Histopathology Datasets | TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas), Camelyon, NCT-CRC-HE-100K, Mass-100K | Large-scale WSI collections for pretraining and benchmarking [29] [32] |

| Software Libraries | TIAToolbox, VISSL, PyTorch, Whole-Slide Data Loaders | Data preprocessing, model implementation, and evaluation pipelines |

| Evaluation Frameworks | HistoPathExplorer, PMCB (Pathology Model Benchmark) | Performance tracking across multiple tasks and datasets [33] |

Integration with Foundation Model Development

The evolution from specialized models to general-purpose foundation models represents a paradigm shift in computational pathology. Both contrastive learning and MIM contribute uniquely to this transition:

Contrastive Learning's Role:

- Established the viability of in-domain pretraining for histopathology

- Demonstrated that multi-institutional datasets with diverse staining protocols improve robustness [29]

- Provided simple yet effective frameworks for representation learning with limited annotations

MIM's Advantages for Foundation Models:

- Superior scalability with model and data size [28]

- Natural extension to multimodal learning (e.g., vision-language models) [8]

- Stronger transfer performance across diverse tissue types and disease categories

- Enhanced few-shot and zero-shot capabilities critical for rare cancer applications

The UNI model exemplifies this transition, having been pretrained on >100 million images from >100,000 H&E-stained WSIs across 20 tissue types using DINOv2 (a MIM-inspired framework). UNI demonstrates remarkable versatility across 34 clinical tasks, including resolution-agnostic tissue classification and few-shot cancer subtyping for up to 108 cancer types in the OncoTree system [32].

The following diagram illustrates how SSL paradigms integrate into the broader foundation model ecosystem:

The comparative analysis of self-supervised learning paradigms in histopathology reveals a clear trajectory toward masked image modeling as the foundational approach for next-generation computational pathology tools. While contrastive learning established the critical principle that in-domain pretraining surpasses transfer learning from natural images, MIM methods like iBOT demonstrate superior performance across diverse tasks, better scaling properties, and stronger generalization to rare cancers and low-data scenarios.

Several emerging trends will shape future developments in this field:

- Multimodal Integration: Combining visual self-supervision with pathology reports and molecular profiles, as exemplified by TITAN, enables more comprehensive representation learning and zero-shot capabilities [8].

- Scaled Architectures: Vision Transformers with hundreds of millions of parameters, pretrained on increasingly diverse histopathology datasets (approaching the petabyte scale), continue to push performance boundaries [32].

- Federated Learning: Self-supervised approaches are being adapted for distributed training across institutions while preserving data privacy, though challenges remain in identifying quality issues without direct data inspection [34].

For researchers and drug development professionals selecting SSL approaches for histopathology applications, MIM frameworks currently offer the most promising path for developing robust, generalizable models, particularly when targeting multiple downstream tasks or working with limited annotations. Contrastive methods remain viable for more focused applications with sufficient annotated data for fine-tuning. As foundation models continue to evolve in computational pathology, the integration of SSL with multimodal data and clinical domain knowledge will ultimately bridge the gap between experimental AI capabilities and routine pathological practice.

Implementation in Precision Oncology: Methodologies and Real-World Applications

In computational pathology, the emergence of foundation models represents a paradigm shift from traditional transfer learning approaches. Traditional transfer learning typically involves taking a model pre-trained on a general dataset (like ImageNet) and fine-tuning it on a specific, often limited, pathology dataset. While beneficial, this method remains constrained by its dependency on large, annotated datasets for each new task and its limited ability to integrate diverse data types. Foundation models, pre-trained on vast and diverse datasets using self-supervised learning, offer a more powerful alternative. They provide generalized representations that can be adapted to numerous downstream tasks with minimal task-specific data, thereby addressing key limitations of traditional methods [8] [35].

Within this context, a critical architectural division has emerged: uni-modal (vision-only) models and multi-modal (vision-language) models. Uni-modal models process exclusively image data, focusing on learning rich visual representations from histopathology slides. In contrast, multi-modal models learn from both images and associated textual data (such as pathology reports), creating a shared representation space that enables a broader range of capabilities, including cross-modal retrieval and zero-shot reasoning [8]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these two model archetypes, focusing on their application within computational pathology research and drug development.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Evaluations across diverse clinical tasks reveal distinct performance profiles for uni-modal and multi-modal foundation models. The table below summarizes quantitative findings from key studies, highlighting the strengths of each archetype.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Uni-Modal vs. Multi-Modal Foundation Models in Pathology Tasks

| Model Archetype | Example Model | Key Performance Metrics | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uni-Modal (Vision-Only) | TITAN-V (Vision-only variant) | High performance in slide-level tasks like cancer subtyping and biomarker prediction [8]. | Standard visual classification, prognosis prediction, tasks where only image data is available. |

| Multi-Modal (Vision-Language) | TITAN (Full vision-language model) | Outperforms slide foundation models in few-shot and zero-shot classification; enables cross-modal retrieval and pathology report generation [8]. | Low-data regimes, rare disease retrieval, tasks requiring integration of visual and textual information. |

The TITAN model exemplifies the power of multi-modal learning. In rigorous benchmarking, it demonstrated superior performance over both region-of-interest (ROI) and slide-level foundation models across multiple machine learning settings, including linear probing, few-shot learning, and zero-shot classification [8]. This is particularly valuable for rare diseases and low-data scenarios, where traditional models struggle. For instance, multi-modal models can retrieve similar cases based on either an image query or a text description of morphological findings, a capability beyond the reach of vision-only systems [8].

However, vision-only models remain highly effective for well-defined visual tasks with sufficient training data. They avoid the complexity and computational overhead of processing multiple modalities and can achieve state-of-the-art results in tasks such as cancer subtyping and outcome prognosis [8]. The choice of archetype, therefore, depends heavily on the specific clinical or research application, data availability, and the need for linguistic understanding.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The development and validation of foundation models in pathology require rigorous and standardized experimental protocols. The following workflow outlines a typical methodology for pre-training and evaluating a multi-modal model like TITAN.

Diagram 1: Foundation Model Pre-training Workflow

Detailed Experimental Methodology

The experimental protocol for a model like TITAN involves a multi-stage pre-training pipeline, as illustrated above [8]:

Data Curation and Preprocessing:

- Vision-Only Pre-training: A large dataset of Whole-Slide Images (WSIs) is required. For TITAN, this involved 335,645 WSIs (Mass-340K dataset) across 20 organ types to ensure diversity [8].

- Multi-Modal Pre-training: This stage requires paired image-text data. This includes both synthetic fine-grained captions for Regions of Interest (ROIs)—423,122 captions generated via a generative AI copilot for pathology—and 182,862 slide-level pathology reports [8].

- ROI Feature Extraction: WSIs are divided into non-overlapping patches (e.g., 512x512 pixels at 20x magnification). A pre-trained patch encoder (e.g., CONCH) is used to extract a feature vector for each patch, creating a 2D feature grid that preserves spatial relationships [8].

Model Pre-training:

- Stage 1 (Uni-Modal, Vision-Only): The model (e.g., a Vision Transformer) is trained on the 2D feature grid using self-supervised learning (SSL) methods like iBOT, which combines masked image modeling and knowledge distillation. This stage teaches the model fundamental histomorphological patterns [8].

- Stage 2 (Multi-Modal, ROI-Text Alignment): The vision model is aligned with text at a fine-grained level using the synthetic ROI captions. This is typically done with contrastive learning, which pulls the representations of matching image-text pairs closer while pushing non-matching pairs apart [8].

- Stage 3 (Multi-Modal, Slide-Report Alignment): The model is further aligned at a broader slide level using the paired WSIs and pathology reports. This step bridges the gap between detailed visual features and overarching diagnostic language [8].

Evaluation and Downstream Tasks:

- The model's general-purpose slide representations are evaluated on diverse clinical tasks without end-to-end fine-tuning ("zero-shot" or with "linear probing"). Key benchmarks include [8]:

- Diagnostic Classification: Cancer subtyping and biomarker prediction.

- Prognosis: Predicting patient outcomes from histology.

- Retrieval: Rare cancer retrieval using image or text queries.

- Generation: Automatic generation of pathology reports from a WSI.

- The model's general-purpose slide representations are evaluated on diverse clinical tasks without end-to-end fine-tuning ("zero-shot" or with "linear probing"). Key benchmarks include [8]:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Successfully developing or applying foundation models in computational pathology requires a suite of key "research reagents." The following table details these essential components.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Pathology Foundation Models

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Large-Scale WSI Datasets | Foundation models require massive, diverse datasets for pre-training. The Mass-340K dataset (335k WSIs) is an example, encompassing multiple organs, stains, and scanner types to learn robust, generalizable features [8]. |

| Paired Image-Text Data | For multi-modal models, high-quality paired data is critical. This includes both synthetic captions for ROIs and real-world pathology reports, enabling the model to link visual patterns with semantic descriptions [8]. |

| Pre-trained Patch Encoder | Models like CONCH convert image patches into feature embeddings. These pre-extracted features form the foundational "vocabulary" for the slide-level transformer model, making training computationally feasible [8]. |

| SSL Algorithms (e.g., iBOT) | Self-supervised algorithms leverage unlabeled data by creating learning signals from the data itself (e.g., reconstructing masked patches). This is the core mechanism for building general visual representations without manual labels [8]. |

| Computational Infrastructure | Training on gigapixel WSIs demands significant resources, including high-memory GPUs and optimized software frameworks (e.g., PyTorch, Transformers), to handle long input sequences and complex model architectures [36] [8]. |

Discussion and Future Directions

The transition from traditional transfer learning to foundation models marks a significant evolution in computational pathology. Uni-modal vision models offer a powerful, direct path for tasks centered purely on image analysis, building on the established principles of deep learning for visual recognition. However, multi-modal vision-language models like TITAN represent a qualitative leap forward. By integrating visual and textual information, they more closely mimic the holistic reasoning process of a pathologist, who correlates microscopic findings with clinical context and descriptive language [8]. This enables novel capabilities such as zero-shot reasoning, cross-modal search, and language-guided interpretation, which are invaluable for drug development in identifying novel biomarkers and stratifying patient populations [37] [38].

Despite their promise, both archetypes face challenges for clinical integration. "Black-box" nature and interpretability issues can hinder clinician trust [36] [37]. Furthermore, multi-modal models introduce additional complexity regarding data privacy, algorithmic bias potentially amplified by biased text reports, and the high computational cost of training and deployment [36] [8]. Future research will focus on improving model interpretability, enhancing generalizability across diverse populations and laboratory protocols, and developing more efficient architectures to make these powerful tools more accessible and trustworthy for routine clinical and research use [36] [39].

This guide provides an objective comparison of three leading foundation models in computational pathology: CONCH, Virchow2, and UNI. Framed within the broader thesis of foundation models versus traditional transfer learning, we detail their technical profiles, performance data, and the experimental protocols used for their evaluation.

Model Specifications and Training Data

The table below summarizes the core architectural and training data specifications for each model.

Table 1: Technical Profiles of CONCH, Virchow2, and UNI

| Feature | CONCH | Virchow2 | UNI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Type | Vision-Language (Multimodal) | Vision-Only | Vision-Only |

| Core Architecture | ViT-B (Image Encoder) & Text Encoder [40] | ViT-H (632M) / ViT-G (1.85B) [41] | ViT-L (ViT-Large) [32] |

| Primary Training Algorithm | Contrastive Learning & Captioning (based on CoCa) [40] | DINOv2 with domain adaptations [41] | DINOv2 [32] |

| Training Data Scale | 1.17 million image-caption pairs [40] | 3.1 million WSIs [41] | 100 million images from 100,000+ WSIs (Mass-100K) [32] |

| Key Data Sources | Diverse histopathology images and biomedical text (e.g., PubMed) [40] [42] | 3.1M WSIs from globally diverse institutions; mixed stains (H&E, IHC) [41] | Mass-100K (H&E stains from MGH, BWH, GTEx) [32] |

Comparative Performance Benchmarks

Independent, large-scale benchmarking reveals how these models perform across clinically relevant tasks. The following table summarizes key results.

Table 2: Comparative Model Performance on Downstream Tasks

| Evaluation Task / Metric | CONCH | Virchow2 | UNI | Notes & Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Average AUROC (31 tasks) | 0.71 [4] | 0.71 [4] | 0.68 [4] | Across morphology, biomarkers, prognosis [4] |

| Morphology (Avg. AUROC) | 0.77 [4] | 0.76 [4] | - | - |

| Biomarkers (Avg. AUROC) | 0.73 [4] | 0.73 [4] | - | - |

| Prognosis (Avg. AUROC) | 0.63 [4] | 0.61 [4] | - | - |

| Rare Cancer Detection (AUC) | - | 0.937 (pan-cancer) [43] | Strong scaling to 108 cancer types [32] | Virchow: 7 rare cancers; UNI: OncoTree evaluation [43] [32] |

| Zero-shot NSCLC Subtyping (Accuracy) | 90.7% [40] | - | - | CONCH outperformed other V-L models [40] |

| Data Efficiency | Superior in full-data settings [4] | Strong in low-data scenarios [4] | - | Virchow2 led more tasks with 75-300 training samples [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

The performance data in this guide is largely derived from a comprehensive, independent benchmark study [4]. The detailed methodology is as follows:

- Models Evaluated: 19 foundation models, including CONCH, Virchow2, and UNI.

- Downstream Tasks: 31 binary classification tasks across 5 morphological classifications, 19 biomarker predictions, and 7 prognostic outcome predictions.

- Datasets: 9,528 slides from 6,818 patients with lung, colorectal, gastric, and breast cancers. All cohorts were external and not used in the pretraining of the evaluated models to prevent data leakage.

- Weakly-Supervised Learning Framework:

- Feature Extraction: Each WSI was divided into non-overlapping tissue patches. Patch-level embeddings were extracted using each foundation model without any fine-tuning.

- Slide-Level Aggregation: A Transformer-based multiple instance learning (MIL) aggregator was trained to make slide-level predictions from the set of patch-level embeddings.

- Evaluation: Model performance was assessed using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) on external test sets. Statistical significance was tested with DeLong's test.

This protocol ensures a fair and clinically relevant comparison by testing the models' ability to produce high-quality, transferable representations for tasks with limited labels.

Model Training Workflows

The diagram below illustrates the core self-supervised learning paradigms used by these foundation models, which enable learning from vast amounts of unlabeled data.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational "reagents" – the software models and datasets essential for research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Computational Pathology

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| CONCH Model | Vision-Language Foundation Model | Enables tasks involving images and/or text: zero-shot classification, cross-modal retrieval, captioning [40] [42]. | Available on GitHub [42] |

| Virchow / Virchow2 Model | Vision-Only Foundation Model | Provides state-of-the-art image embeddings for slide-level tasks like pan-cancer detection and biomarker prediction [43]. | - |

| UNI Model | Vision-Only Foundation Model | General-purpose image encoder for diverse tasks; demonstrates scaling laws and few-shot learning capabilities [32]. | - |

| DINOv2 Algorithm | Self-Supervised Learning Framework | Core training method for vision-only models; uses a student-teacher framework with contrastive objectives to learn robust features [41] [32]. | - |

| TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) | Public Dataset | A common benchmark dataset for training and evaluating computational pathology models [5]. | - |

| Multiple Instance Learning (MIL) Aggregator | Machine Learning Model | Aggregates patch-level embeddings from a whole slide image to make a single slide-level prediction, enabling weakly supervised learning [4]. | Transformer-based, ABMIL |