Mechanistic Models vs. AI in Tumor Modeling: A New Paradigm for Computational Oncology

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the distinct yet complementary roles of mechanistic models and artificial intelligence (AI) in computational oncology.

Mechanistic Models vs. AI in Tumor Modeling: A New Paradigm for Computational Oncology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the distinct yet complementary roles of mechanistic models and artificial intelligence (AI) in computational oncology. We explore the foundational principles of both approaches, from mechanism-driven mathematical theories to data-hungry machine learning algorithms. The scope covers their methodological applications in diagnosis, treatment prediction, and drug discovery, alongside a critical examination of challenges like data scarcity, model interpretability, and clinical validation. By synthesizing current advancements and comparative studies, this review aims to guide the strategic integration of these modeling paradigms to accelerate the development of personalized cancer therapies and improve patient outcomes.

Core Principles: From Biological Mechanisms to Data Patterns

In the field of mathematical oncology, two distinct yet complementary approaches have emerged for modeling tumor biology and treatment response: mechanistic models and AI/machine learning (ML) models [1]. Mechanistic models are knowledge-driven constructs that use mathematical equations to represent our current understanding of biological processes, grounded in the fundamental principles of biology, chemistry, and physics [1]. In contrast, AI/ML models are data-driven approaches that extract hidden patterns and relationships from large datasets without requiring explicit knowledge of the underlying biology [2]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, focusing on their implementation, performance, and applicability in cancer research and drug development.

Background: Core Principles and Applications

Knowledge-Driven Mechanistic Modeling

Mechanistic mathematical models are abstract, simplified mathematical constructs created to represent parts of biological reality for a particular purpose [1]. In oncology, they describe the behavior of complex cancer systems based on understanding of underlying mechanisms rooted in fundamental biology [1]. These models deliberately approximate reality through equations or rules, with inevitable simplifying assumptions such as reduced dimensionality, dynamic processes approximated as time-invariant, or biological pathways reduced to key components [1].

Common applications in cancer research include investigating somatic cancer evolution and treatment, simulating different radiotherapy fractionation schemes, modeling treatment-induced tumor resistance, and simulating in silico trials for hypothesis generation [1]. The quality of these approximations is validated with data, and their strength lies in generating insights through simulation of unobserved scenarios, even in the absence of experimental data [1].

Data-Driven AI/ML Modeling

AI and machine learning approaches excel at identifying patterns in high-dimensional datasets without requiring specific knowledge about the underlying biology [2]. These models are particularly valuable when only incomplete or limited knowledge is available for a study [2]. In cancer metabolism research, for example, ML techniques have been applied to diverse data sources including RNA-seq data, multi-omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics, phosphoproteomics, and fluxomics), and FDG-PET/CT imaging data [2].

Common applications in oncology include drug response prediction, molecular tumor subtype identification, volumetric tumor segmentation, image-based outcome predictions, and automated intervention planning [1]. The flexibility of highly parameterized models like deep neural networks allows them to approximate complex and mechanistically unknown relationships, functioning as "universal function approximators" [1].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Analysis

A direct comparison study evaluated the performance of mechanistic modeling versus machine learning approaches for predicting breast cancer cell growth dynamics in response to glucose transporter inhibition [2]. The study tracked growth of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells treated with Cytochalasin B (a GLUT1 inhibitor) using time-resolved microscopy and compared predictions across modeling approaches.

Table 1: Model Performance Comparison for Predicting Tumor Cell Growth

| Model Type | Specific Approach | Prediction Accuracy (R²) | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning | Random Forest | 0.92 | Highest predictive accuracy | Limited biological interpretability |

| Machine Learning | Decision Tree | 0.89 | Good balance of accuracy/interpretability | Prone to overfitting |

| Machine Learning | K-Nearest Neighbor | 0.84 | Simple implementation | Performance depends on feature selection |

| Mechanistic | ODE Model | 0.77 | Biological interpretability, mechanism elucidation | Lower accuracy than top ML models |

| Machine Learning | Linear Regression | 0.69 | Simple, fast computation | Limited complexity handling |

The quantitative comparison reveals that while the random forest model provided the highest predictive accuracy (R² = 0.92), the mechanism-based model demonstrated respectable predictive capability (R² = 0.77) with the significant added benefit of elucidating biological mechanisms [2]. This trade-off between predictive accuracy and biological interpretability represents a fundamental consideration when selecting modeling approaches for specific research objectives.

Methodologies: Experimental and Computational Workflows

Mechanistic Model Development Process

The development of mechanistic models follows a structured workflow that integrates biological knowledge with mathematical formalization:

Table 2: Mechanistic Model Development Protocol

| Step | Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. System Definition | Identify key biological components and interactions | Balance comprehensiveness with simplicity |

| 2. Mathematical Formalization | Translate biological mechanisms into equations (ODEs, PDEs, ABMs) | Select appropriate mathematical framework |

| 3. Parameter Estimation | Calibrate model parameters using experimental data | Address parameter identifiability challenges |

| 4. Model Validation | Test predictions against independent datasets | Ensure biological plausibility beyond fit quality |

| 5. Experimental Testing | Generate and test novel biological predictions | Use model to guide future experiments |

For example, in developing a model for tumor metabolism, researchers create a mechanistic framework incorporating key metabolic pathways active in tumor cells, including glycolysis, TCA cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, and glutaminolysis [3]. The dynamics of metabolite concentrations are modeled using ordinary differential equations with mathematical expressions describing enzyme activities and kinetic parameters obtained from literature [3].

Machine Learning Implementation Workflow

The implementation of machine learning models for cancer research follows a different pathway focused on data processing and algorithm selection:

- Data Collection and Preprocessing: Acquire and clean relevant datasets (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics, imaging data)

- Feature Selection: Identify the most predictive variables from high-dimensional data

- Model Selection: Choose appropriate ML algorithms based on data characteristics and research questions

- Training and Validation: Implement cross-validation strategies to prevent overfitting

- Performance Evaluation: Assess model accuracy using appropriate metrics (e.g., R², AUC-ROC)

In the breast cancer cell growth prediction study, researchers compared four common ML models: random forest, decision tree, k-nearest-neighbor regression, and linear regression, using time-resolved microscopy data for training and validation [2].

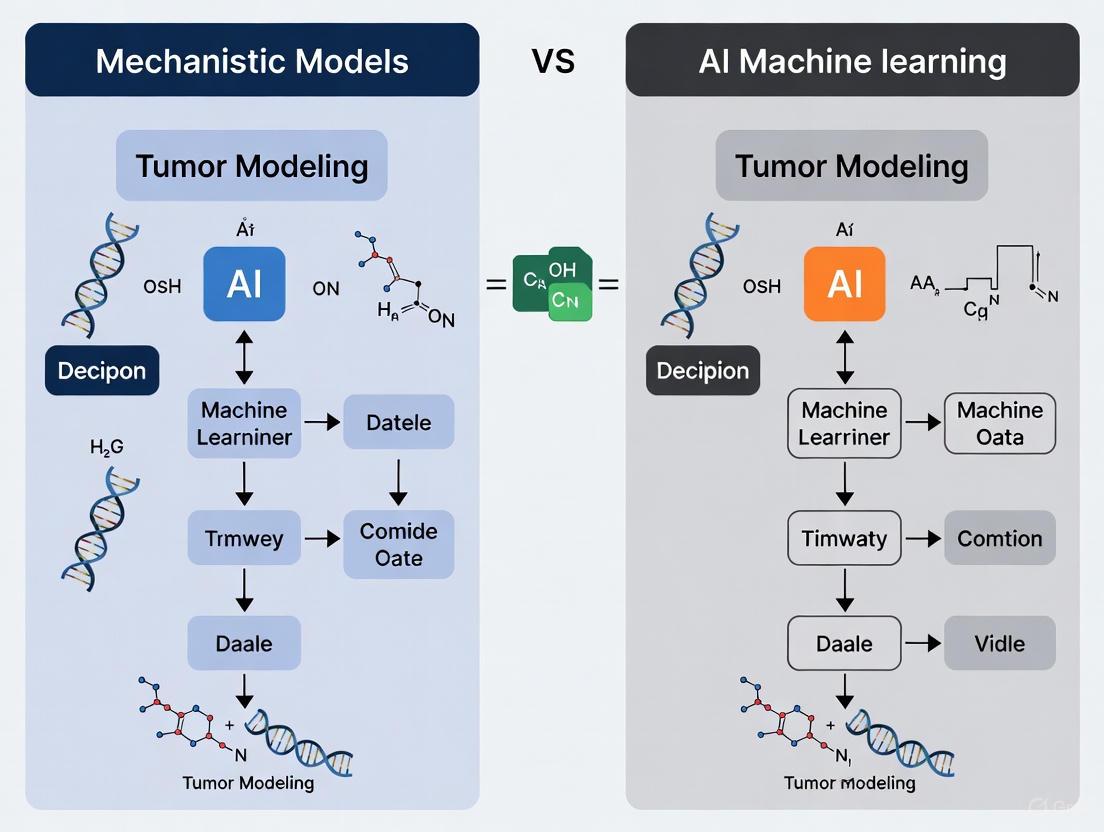

Visualizing Model Integration: The Hybrid Approach

The emerging field of mechanistic learning represents the synergistic combination of mechanistic mathematical modeling and data-driven machine or deep learning [1]. This integration can be visualized through the following workflow:

Research Reagent Solutions for Tumor Modeling

Implementing either modeling approach requires specific experimental resources and computational tools. Below is a compilation of key research reagents and their applications in generating data for model development and validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| MDA-MB-231 Cell Line | Triple-negative breast cancer model system | Studying glucose metabolism and inhibitor response [2] |

| Cytochalasin B | Competitive GLUT1 glucose transporter inhibitor | Perturbing glucose uptake to study metabolic adaptations [2] |

| IncuCyte S3 Live-Cell Imaging | Time-resolved microscopy and cell confluence tracking | Longitudinal monitoring of tumor cell growth dynamics [2] |

| Cytotox Red Reagent | Fluorescent dead cell indicator | Quantifying cell death in response to metabolic inhibition [2] |

| GLUT1 Inhibitors | Targeting glucose transport machinery | Investigating metabolic vulnerabilities in cancer cells [2] |

| Multi-omics Datasets | Transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics data | Training AI/ML models and validating mechanistic models [4] |

| Immune Checkpoint Reagents | Antibodies targeting PD-1, CTLA-4, LAG3, etc. | Studying tumor-immune interactions in QSP models [4] |

Applications and Future Directions

The integration of mechanistic and AI approaches through mechanistic learning represents the future of computational oncology [1]. This hybrid framework leverages the strengths of both paradigms: the interpretability and biological grounding of mechanistic models, and the pattern recognition capabilities and adaptability of AI/ML [5].

Four categories of mechanistic learning have emerged:

- Sequential: Using model outputs as inputs for another model

- Parallel: Independent modeling with integrated interpretation

- Extrinsic: Using external knowledge to constrain AI models

- Intrinsic: Building biological mechanisms directly into model architectures [1]

These approaches are particularly valuable for addressing complex challenges in oncology research, including longitudinal tumor response predictions and time-to-event modeling [1]. As the field advances, mechanistic learning frameworks show great promise for addressing persistent challenges in oncology such as limited data availability, requirements for model transparency, and integration of complex multi-scale data [1].

The concept of patient-specific digital twins - virtual replicas that simulate disease progression and treatment response - represents one of the most promising clinical applications of these integrated modeling approaches [5]. These computational avatars integrate real-time patient data into mechanistic frameworks enhanced by AI, enabling personalized treatment planning and therapeutic strategy optimization [5].

The field of oncology is witnessing a paradigm shift in how tumors are modeled and understood, characterized by a tension between traditional mechanistic models and emerging artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML) approaches. Mechanistic models are grounded in established biological theory, representing tumor behavior through mathematical equations derived from known physics and biology, such as partial differential equations describing drug diffusion or cell proliferation dynamics. In contrast, AI/ML models are data-driven, learning complex patterns directly from large-scale oncology datasets without requiring pre-specified biological rules [5]. This guide explores how these AI/ML models function as powerful tools for pattern recognition, objectively comparing their performance against traditional methods and mechanistic modeling approaches across key oncology applications.

Core Principles: How AI/ML Models Recognize Patterns in Oncology Data

AI/ML models in oncology excel at identifying multidimensional relationships within complex datasets that often elude human perception or traditional statistical methods. Their operation hinges on several key principles:

Feature Hierarchy Learning: Deep learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), automatically learn hierarchical representations of oncology data. In pathology image analysis, for instance, initial layers might detect simple edges and textures, intermediate layers identify cellular structures, and deeper layers recognize complex tissue architectures indicative of malignancy [6] [7].

Multimodal Data Integration: Advanced AI models fuse heterogeneous data types—including genomic sequences, medical images, clinical records, and protein expressions—to generate more comprehensive predictions. This integration enables the discovery of cross-modal relationships, such as correlating specific genetic mutations with distinctive radiological features visible on CT scans [6] [7].

Nonlinear Pattern Recognition: Unlike traditional statistical methods that often assume linear relationships, ML algorithms capture complex nonlinear interactions between variables. This capability is particularly valuable in tumor ecosystems where biological processes frequently exhibit threshold effects, feedback loops, and complex interdependencies [5] [8].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow of a data-driven AI/ML model for pattern recognition in oncology, contrasting with hypothesis-driven mechanistic approaches:

Performance Comparison: AI/ML Models Versus Traditional Methods

Diagnostic and Prognostic Performance Across Cancer Types

AI/ML models have demonstrated compelling performance advantages across multiple oncology domains, particularly in diagnostic imaging and survival prediction, as quantified in numerous clinical validation studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI/ML Models Versus Traditional Methods in Cancer Diagnosis

| Cancer Type | AI/ML Model | Traditional Method | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | Deep Learning (Mammography) | Radiologist Interpretation | Superior sensitivity (reduced false negatives by 9.4%) and specificity (reduced false positives by 5.7%) | [9] |

| Lung Cancer | CheXNeXt CNN (Chest X-ray) | Board-certified Radiologists | 52.3% greater sensitivity for masses, 20.4% greater sensitivity for nodules with comparable specificity | [7] |

| Colorectal Cancer | AI-assisted Colonoscopy (CADe) | Standard Colonoscopy | Higher adenoma detection rates; Sensitivity: 97%, Specificity: 95% | [9] [7] |

| Prostate Cancer | Validated AI System (MRI) | Radiologist Assessment | Superior AUC (0.91 vs 0.86); detected more cases of Gleason grade group ≥2 cancers at same specificity | [7] |

| Multiple Cancers | DL in Digital Pathology | Manual Pathology Review | Reduced interpretation variability; Automated tumor-stroma ratio quantification prognostic for survival | [6] [10] |

Table 2: Performance of AI/ML Models in Prognostic Prediction and Therapeutic Guidance

| Clinical Application | AI/ML Model | Comparison Baseline | Performance Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced HCC Survival Prediction | StepCox (forward) + Ridge (101 models tested) | Conventional Staging | C-index: 0.68 (training), 0.65 (validation); 1-2 year AUC: 0.72-0.75 | [11] |

| Bladder Cancer Recurrence | Multi-modal ML (Radiomics + Clinical + Genomic) | Conventional Statistical Models | Superior recurrence prediction accuracy | [8] |

| Prostate Cancer PSA Persistence | Random Forest | Traditional Clinical Nomograms | AUC: 0.861 (training), 0.801 (test set) | [8] |

| Immunotherapy Response | Deep Learning on Pathology Slides | Pathologist Assessment | Identification of histomorphological features correlating with response to immune checkpoint inhibitors | [12] |

Comparison with Mechanistic Modeling Approaches

The performance advantages of AI/ML models must be contextualized within the broader modeling landscape, particularly in relation to traditional mechanistic approaches.

Table 3: AI/ML Models Versus Mechanistic Models in Oncology Research

| Characteristic | AI/ML Models | Mechanistic Models |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Basis | Data-driven pattern recognition | First principles of biology and physics |

| Data Requirements | Large, annotated datasets for training | Detailed mechanistic parameters |

| Interpretability | Often "black box"; limited biological insight | High interpretability with clear biological mechanisms |

| Generalizability | May fail with out-of-distribution data | Better extrapolation to novel conditions |

| Computational Demand | High during training, variable during inference | Often computationally intensive for simulation |

| Key Strength | Superior accuracy with sufficient data | Hypothesis testing and theoretical understanding |

| Regulatory Status | Multiple FDA-approved devices (71 in radiology, pathology) [13] | Mainly research use; limited clinical adoption |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for AI/ML Model Validation

Protocol: Development and Validation of Survival Prediction Models

The following methodology, derived from a study on hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) survival prediction, exemplifies rigorous AI/ML model development [11]:

Cohort Selection and Data Collection:

- Enroll 175 HCC patients with balanced baseline characteristics

- Inclusion criteria: BCLC stage B or C, Child-Pugh class A or B liver function, complete clinical data

- Collect multimodal data: clinical parameters (Child-Pugh score, BCLC stage), tumor characteristics (size, number), treatment variables (radiotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy)

Data Preprocessing and Cohort Division:

- Perform propensity score matching to balance baseline characteristics between treatment groups

- Randomly divide patients into training (60%) and validation (40%) cohorts

- Conduct univariate Cox regression to identify prognostic factors (p < 0.05) for model inclusion

Model Training and Selection:

- Implement 101 different machine learning algorithms on the training cohort

- Include Cox proportional hazards models, regularized Cox models (Ridge, Lasso, Elastic Net), survival trees, and ensemble methods

- Train each model using identified prognostic variables ("Child," "BCLC stage," "Size," "Treatment")

Performance Validation:

- Assess model performance using concordance index (C-index) in both training and validation cohorts

- Perform time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis at 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival endpoints

- Select best-performing model based on validation cohort performance (StepCox [forward] + Ridge model achieving C-index: 0.65)

Clinical Implementation:

- Generate risk score stratification for patient prognosis

- Enable individualized prognostic assessment to guide treatment decisions

Protocol: AI-Assisted Diagnostic Model Development

For diagnostic applications such as cancer detection in medical images, a different methodological approach is employed [9] [6]:

Dataset Curation:

- Collect large-scale annotated datasets (e.g., 10,000-100,000 images)

- Obtain expert annotations (radiologists/pathologists) for ground truth labels

- Ensure diverse representation across demographics, cancer subtypes, and imaging equipment

Model Architecture Selection:

- Implement convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for image-based tasks

- Utilize transfer learning from pre-trained models when sample size is limited

- Design custom architectures optimized for specific imaging modalities (mammography, CT, pathology whole-slide images)

Training Methodology:

- Apply data augmentation techniques (rotation, flipping, contrast adjustment) to improve generalization

- Utilize progressive training strategies that leverage both strongly and weakly labeled data

- Implement regularization methods (dropout, weight decay) to prevent overfitting

Validation Framework:

- Conduct multi-center external validation on independent datasets

- Compare AI performance against human experts in blinded evaluations

- Assess diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, area under ROC curve, and clinical workflow impact

The following diagram illustrates the integrated approach combining AI/ML pattern recognition with mechanistic modeling principles, representing the future of computational oncology:

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for AI/ML Oncology Research

The development and validation of AI/ML models in oncology requires specialized data resources and computational tools that function as essential "research reagents" in this domain.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for AI/ML Oncology Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in AI/ML Research | Access Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curated Cancer Databases | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Genomic Data Commons | Provides multimodal training data (genomics, images, clinical) for model development | Publicly available with data use agreements |

| AI/ML Software Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Scikit-learn | Enables implementation of deep learning and machine learning algorithms | Open-source with community support |

| Medical Imaging Archives | Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA), LIDC-IDRI | Curated repositories of radiological images with annotations for computer vision applications | De-identified data available for research use |

| Computational Infrastructure | High-performance Computing (HPC) clusters, Cloud GPUs | Provides necessary processing power for training complex models on large datasets | Institutional resources or commercial cloud services |

| Biobanks with Digital Pathology | Institutional biobanks with whole-slide imaging | Digitized histopathology slides for development of computational pathology algorithms | Requires institutional review board approval |

| Clinical Trial Data Repositories | Project Data Sphere, NCTN Navigator | Anonymized clinical trial data for model validation across diverse populations | Controlled access for research purposes |

The comparison between AI/ML models and traditional mechanistic approaches reveals a complementary rather than competitive relationship. AI/ML models demonstrate superior performance in tasks requiring pattern recognition within complex, high-dimensional oncology datasets, consistently matching or exceeding human expert performance and traditional statistical methods across diagnostic and prognostic applications [9] [11] [7]. However, mechanistic models retain crucial advantages in interpretability, hypothesis testing, and extrapolation beyond available data.

The most promising future direction lies in hybrid frameworks that leverage the strengths of both approaches [5]. These integrated models use AI/ML for parameter estimation from real-world data while maintaining mechanistic biological constraints, creating "digital twins" that can simulate individual patient disease progression and treatment response [5] [12]. As the field advances, overcoming challenges related to data quality, model interpretability, and regulatory standardization will be essential for translating these powerful pattern recognition tools into routine clinical practice, ultimately enabling more precise, personalized, and effective cancer care.

In the pursuit of overcoming cancer, researchers increasingly rely on computational models to understand tumor dynamics and treatment resistance. Two distinct philosophical approaches have emerged: hypothesis-driven modeling, rooted in mechanistic biological understanding, and correlation-based modeling, which leverages statistical patterns in large datasets. The former builds on established biological principles to explain how and why tumors behave as they do, while the latter identifies predictive relationships from data without necessarily requiring mechanistic insight. Within tumor modeling research, this dichotomy represents a fundamental tension between mechanistic models derived from first principles and artificial intelligence/machine learning approaches that excel at finding patterns in complex data. Both approaches offer distinct advantages and limitations, with the choice depending on research objectives, data availability, and the desired interpretability of results. This guide objectively compares these competing philosophies through their application in oncology, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate methodologies for specific drug development challenges.

Core Philosophical Differences and Mathematical Foundations

The distinction between hypothesis-driven and correlation-based modeling begins with their fundamental philosophical underpinnings and extends to their mathematical implementation.

Hypothesis-driven modeling follows a deductive approach, beginning with a specific biological hypothesis about system mechanisms. These models incorporate established biological knowledge and physical laws, with parameters typically corresponding to measurable biological properties. For example, in tumor growth modeling, parameters might represent proliferation rates, carrying capacity, or drug effect rates [14]. The model structure itself embodies testable hypotheses about underlying mechanisms, such as including separate compartments for proliferative and quiescent cells based on the hypothesis that these populations behave differently under treatment [14].

Correlation-based modeling employs an inductive approach, discovering patterns and relationships directly from data without pre-specified mechanistic assumptions. Parameters in these models often lack direct biological interpretation, instead serving to maximize predictive accuracy. The model structure is typically chosen for flexibility rather than biological plausibility, potentially including complex interaction terms that statistically capture relationships without mechanistic explanation [15].

The table below summarizes the fundamental distinctions between these approaches:

Table 1: Core Philosophical Differences Between Modeling Approaches

| Aspect | Hypothesis-Driven Modeling | Correlation-Based Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Explain underlying mechanisms | Predict outcomes accurately |

| Approach | Deductive (theory → model → data) | Inductive (data → model → patterns) |

| Parameter Interpretability | High (parameters map to biology) | Low (parameters often not interpretable) |

| Knowledge Source | Prior biological knowledge | Patterns in datasets |

| Validation Focus | Biological plausibility & predictive accuracy | Predictive accuracy & generalization |

| Causal Claims | Directly testable through model structure | Limited to association without experimentation |

The mathematical foundations further distinguish these approaches. Hypothesis-driven models often employ differential equations that embody biological mechanisms. For instance, ordinary differential equations can characterize tumor burden dynamics:

Table 2: Common Mathematical Frameworks in Tumor Modeling

| Model Type | Mathematical Formulation | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Exponential Growth | dT/dt = kg · T | Unconstrained growth with intrinsic rate kg |

| Logistic Growth | dT/dt = kg · T · (1 - T/Tmax) | Growth with carrying capacity Tmax |

| Gompertz Growth | dT/dt = kg · T · ln(Tmax/T) | Asymmetric growth deceleration |

| Two-Compartment | dP/dt = f(P) - m1 · P + m2 · QdQ/dt = m1 · P - m2 · Q | Distinguishes proliferative (P) and quiescent (Q) cells |

In contrast, correlation-based approaches utilize statistical learning methods. The relationship between model complexity and generalization capability illustrates a key consideration. As complexity increases (e.g., through higher-degree polynomial terms), models fit training data better but may fail to generalize to new data—a phenomenon known as overfitting [15]. Cross-validation techniques help identify the optimal complexity that balances fit and generalizability [15].

Diagram 1: Contrasting Modeling Workflows. This flowchart illustrates the divergent pathways for hypothesis-driven (red) and correlation-based (green) approaches, ultimately converging toward integrated modeling solutions.

Quantitative Comparison in Tumor Modeling Applications

Direct comparison of hypothesis-driven and correlation-based modeling approaches reveals significant differences in their performance characteristics, interpretability, and implementation requirements across various tumor modeling applications.

Table 3: Performance Comparison in Tumor Modeling Applications

| Characteristic | Hypothesis-Driven Models | Correlation-Based Models |

|---|---|---|

| Predictive Accuracy | Moderate to high for mechanisms within model scope | Potentially very high, especially for complex patterns |

| Extrapolation Reliability | High (principled extension of mechanisms) | Low (limited to training data domains) |

| Data Requirements | Lower (parameters can come from separate experiments) | Very high (large datasets needed for training) |

| Computational Demand | Variable (often moderate) | Typically high (especially for training) |

| Interpretability | High (mechanisms explicitly represented) | Low ("black box" problem) |

| Handling Novel Conditions | Strong (based on first principles) | Weak (requires retraining with new data) |

| Implementation Timeline | Longer (model development and validation) | Shorter (using established algorithms) |

The deGeco model for genomic compartments in Hi-C data exemplifies hypothesis-driven advantages, demonstrating high robustness and accurate inference of interaction probability maps from extremely sparse data without parameter training [16]. This approach enabled clear biological insights, including evidence of multiple chromatin states with different self-interaction affinities [16].

Correlation-based approaches face fundamental limitations in establishing causal relationships. The principle that "correlation does not imply causation" is particularly relevant in tumor modeling, where spurious correlations may lead to incorrect conclusions [17] [18]. For example, a correlation between a biomarker and tumor progression might result from a third, unmeasured variable rather than a direct causal relationship [18]. This limitation becomes particularly problematic in high-dimensional datasets where the "curse of dimensionality" increases the risk of finding spurious correlations by chance alone [17].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Rigorous experimental protocols are essential for developing and validating both hypothesis-driven and correlation-based models in tumor research. The methodologies differ significantly between approaches.

Hypothesis-Driven Model Development Protocol

The development of hypothesis-driven models follows a systematic workflow with distinct stages:

Hypothesis Formulation: Precisely define the biological mechanism to be investigated, such as "cohesin-mediated loop extrusion explains TAD formation" or "hypoxia-driven angiogenesis follows a diffusion-limited process" [16].

Model Structural Design: Translate biological hypotheses into mathematical structures using appropriate formalisms. For tumor growth, this might involve selecting between ordinary differential equations (ODEs) for population dynamics, partial differential equations (PDEs) for spatial processes, or hybrid approaches [14]. The Bienenstock-Cooper-Munro (BCM) rule in neuroscience provides an exemplary case where a phenomenological model was later reproduced using mechanistic models with increasing biological detail [19].

Parameter Estimation: Determine parameter values through direct experimental measurement (e.g., proliferation rates from imaging data) or model calibration to experimental observations [20]. The deGeco model utilizes maximum likelihood estimation via optimization algorithms like L-BFGS-B to fit parameters to Hi-C interaction frequency data [16].

Model Validation: Test model predictions against independent datasets not used in parameter estimation. For example, a model predicting tumor response to a novel therapeutic combination should be validated against experimental results in animal models or clinical trial data [20].

Experimental Testing: Design targeted experiments to test specific model predictions and potentially falsify the underlying hypotheses. This iterative process refines both the model and biological understanding [21].

Correlation-Based Model Development Protocol

Correlation-based modeling employs a different methodological approach focused on pattern discovery:

Feature Selection: Identify which variables or features to include in the model. Correlation analysis helps remove redundant features (redundancy) and detect multicollinearity, which can undermine model stability [22]. Techniques like principal component analysis (PCA) may be used to reduce dimensionality while preserving predictive information [16] [22].

Algorithm Selection: Choose appropriate machine learning algorithms based on data characteristics and prediction goals. Options range from regression models for continuous outcomes to classification algorithms for categorical endpoints like treatment response versus resistance [22].

Training-Testing Split: Partition data into training sets for model development and validation sets for performance assessment. Cross-validation techniques, such as leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV), provide robust estimates of model generalizability [15].

Performance Metrics: Evaluate models using appropriate metrics including R-squared for variance explained, root mean square error (RMSE) for prediction accuracy, and area under the curve (AUC) for classification tasks [15].

Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize model parameters that control the learning process rather than representing biological quantities. This typically involves systematic exploration of parameter spaces and validation against held-out data [15].

Diagram 2: Methodological Validation Pathways. The validation approaches differ fundamentally, with hypothesis-driven methods (red) testing mechanistic predictions, while correlation-based methods (green) focus on statistical generalizability.

Successful implementation of both modeling approaches requires specific computational tools, data resources, and methodological frameworks. The table below details essential components of the modern computational oncologist's toolkit.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Function | Primary Modeling Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Imaging (MRI/PET) | Provides spatial-temporal data on tumor anatomy, cellularity, perfusion, metabolism | Both (mechanistic initialization/feature source) |

| Hi-C Genomic Data | Measures genome-wide chromatin interaction frequencies | Hypothesis-driven (genomic compartment modeling) |

| Single-Cell Sequencing | Resolves intratumor heterogeneity and cell population dynamics | Both (mechanism refinement/feature identification) |

| Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) | Models population dynamics and treatment responses | Hypothesis-driven |

| Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) | Captures spatial invasion and microenvironment interactions | Hypothesis-driven |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Identifies dominant patterns in high-dimensional data | Correlation-based (also used in hypothesis-driven) |

| Cross-Validation Methods | Estimates model generalizability to new data | Correlation-based |

| FAIR Data Principles | Ensures findability, accessibility, interoperability, reusability | Both (enhances reproducibility and integration) |

Medical imaging technologies particularly MRI and PET represent crucial data sources for both approaches, providing non-invasive, spatially-resolved measurements of tumor biology including cellularity (via DW-MRI), vascularity (via DCE-MRI), and metabolism (via FDG-PET) [20]. These imaging modalities can initialize mechanistic models or serve as feature sources for correlation-based approaches.

The FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles have emerged as critical guidelines for both data and model management, supporting integration across modeling philosophies and biological scales [19]. Applying these principles to models and modeling workflows increases transparency, enables validation, and facilitates model reuse and extension [19].

Integrated Approaches and Future Directions

The dichotomy between hypothesis-driven and correlation-based modeling represents a false choice when considering advanced cancer modeling approaches. The most promising future direction lies in integrated methodologies that leverage the strengths of both philosophies while mitigating their respective limitations.

Hybrid approaches are increasingly emerging, where machine learning methods help parameterize mechanistic models or generate hypotheses from complex data, while mechanistic insights constrain and regularize data-driven models to enhance biological plausibility [20] [19]. For example, AI can relate large quantities of 'omic' data to mechanistic model parameters, reducing computational burden or parsing mechanistic model forecasts to select optimal therapies [20]. Similarly, the deGeco model represents a generative probabilistic approach that incorporates both hypothesis-driven mechanistic assumptions and data-driven parameter inference [16].

The FAIR principles provide a framework for this integration by making both models and data findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable [19]. This enables researchers to combine models representing different biological scales and built using different modeling philosophies, ultimately enhancing our understanding of multiscale cancer phenomena [19]. Integrated workflows might use correlation-based approaches to identify novel patterns in high-dimensional data, then employ hypothesis-driven modeling to explain these patterns through testable biological mechanisms, creating a virtuous cycle of discovery and validation.

For drug development professionals, this integration offers a path toward models that are both predictively accurate and mechanistically interpretable—critical requirements for regulatory acceptance and clinical implementation. As these approaches mature, they promise to accelerate the development of personalized cancer therapies guided by predicted patient response rather than observed outcomes, potentially dramatically improving patient outcomes [20].

The field of computational oncology is increasingly divided between two powerful, yet philosophically distinct, modeling approaches: mechanistic models rooted in biological first principles and data-driven artificial intelligence (AI) models that learn patterns from complex datasets. The selection and initialization of these models are fundamentally guided by the available data types, each with unique strengths and limitations for capturing tumor biology. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three cornerstone data categories—medical imaging, genomics, and clinical records—examining their respective roles in initializing and informing both mechanistic and AI-based modeling paradigms. By objectively evaluating their applications, technical requirements, and performance across experimental settings, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge to make informed decisions in model selection and development for precision oncology.

Comparative Analysis of Key Data Types

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, applications, and challenges of the three primary data types used in computational oncology.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Data Types for Tumor Model Initialization

| Data Type | Key Subtypes & Sources | Primary Modeling Applications | Technical & Practical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Imaging [23] [20] | - Anatomic: CT, MRI- Physiologic/Molecular: DWI-MRI, DCE-MRI, FDG-PET- Digital Pathology: Whole-slide images (WSI) | - Tumor growth models [20]- Radiogenomics (linking features to genomics) [23]- AI-based segmentation & diagnosis [1] | - Spatial Resolution: 1-5 mm (clinical); sub-millimeter (microscopy) [20]- Challenges: Standardization of feature extraction; domain shift in digital pathology [23] [20] |

| Genomics [23] [24] [25] | - DNA-level: Somatic mutations, Copy Number Alterations (CNAs), Structural Variants (SVs) from WGS/WES/targeted panels [26] [25]- RNA-level: Gene expression (mRNA-seq) [25]- Epigenomics: DNA methylation [25] | - Molecular subtyping and classification [26] [1]- Predicting variant pathogenicity and drug response [24]- Informing mechanistic pathways | - Panel vs. WGS/WES: Targeted panels (e.g., MSK-IMPACT) are clinically scalable; WGS/WES are more comprehensive but costly [26]- Challenges: Distinguishing driver from passenger mutations; data interpretation [24] |

| Clinical Records [27] [28] [29] | - Demographics: Age, sex [29]- Lifestyle/Behavioral: Smoking status, BMI [29]- Medical History: Comorbidities, family history [29]- Longitudinal EHR Data: Diagnoses, medications, lab results [28] | - Survival and time-to-event analysis [29]- Population health and risk stratification [24]- Augmenting omics analyses via transfer learning [28] | - Data Structure: Often requires mapping and harmonization from heterogeneous EHR systems [27] [29]- Bias: Can reflect hospital-entry bias and lack population representativeness [24] |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Protocol 1: AI for Tumor-Type Classification from Genomic Data

The OncoChat study demonstrates the application of a large language model (LLM) to classify tumor types using genomic alterations [26].

- Objective: To accurately classify 69 different tumor types, including Cancers of Unknown Primary (CUP), based on genomic features.

- Data Initialization:

- Source: American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Project GENIE consortium.

- Sample Size: 163,585 targeted panel sequencing samples.

- Genomic Features: Single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), copy number alterations (CNAs), and structural variants (SVs) were preprocessed into a dialogue format suitable for LLM instruction-tuning.

- Modeling Approach: The OncoChat model was developed by fine-tuning a foundational LLM on the formatted genomic data from 158,836 samples with known primaries (CKP).

- Performance Metrics [26]:

- On a test set of 19,940 CKP cases, OncoChat achieved an accuracy of 0.774 and an F1 score of 0.756.

- It outperformed existing models like OncoNPC (accuracy: 0.718) and GDD-ENS (accuracy: 0.616).

- For CUP classification, the model correctly identified 22 out of 26 cases (84.6%) with subsequently confirmed tumor types.

Protocol 2: Integrating EHR and Omics via Transfer Learning

The COMET framework leverages large-scale Electronic Health Record (EHR) data to enhance the analysis of smaller omics datasets [28].

- Objective: To improve predictive modeling from high-dimensional omics data (e.g., proteomics) by pretraining on larger, related EHR datasets.

- Data Initialization:

- EHR Pretraining Cohort: 30,843 pregnant patients from Stanford STARR OMOP database.

- Omics Cohort: A subset of 61 patients with targeted proteomics data (1,317 proteins) from serial blood samples.

- Modeling Approach:

- Step 1: A model was pretrained on the large EHR-only cohort to predict "days to labour."

- Step 2: The learned weights were transferred to a multimodal network that integrated both EHR and proteomics data from the smaller omics cohort.

- Performance Metrics [28]:

- COMET achieved a strong Pearson correlation (r = 0.868) between predicted and actual days to labour, significantly outperforming baselines.

- Baseline Comparisons:

- EHR-only baseline: r = 0.768

- Proteomics-only baseline: r = 0.796

- Joint baseline (without pretraining): r = 0.815

Protocol 3: Predicting Time-to-Cancer Diagnosis with Clinical Data

This study used traditional survival analysis and machine learning on clinical and demographic data to predict cancer risk [29].

- Objective: To develop and validate models for predicting the time to first diagnosis for several high-incidence cancers.

- Data Initialization:

- Training Data: 141,979 participants from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial.

- Validation Data: 287,150 participants from the UK Biobank (UKBB).

- Features: 46 sex-agnostic features, including demographics, clinical history, and behavioral data.

- Modeling Approach: Cox proportional hazards model with elastic net regularization was compared against non-parametric methods like survival decision trees and random survival forests.

- Performance Metrics [29]:

- The Cox model achieved a C-index of 0.813 for lung cancer prediction.

- Cancer-specific models consistently outperformed non-specific cancer models.

- The model provided interpretable insights, such as an inverse association between BMI and lung cancer risk.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a synergistic workflow that integrates multiple data types to inform both AI and mechanistic modeling paradigms, leveraging the strengths of each approach.

The table below lists key datasets, platforms, and tools that form the foundation of modern computational oncology research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Computational Oncology

| Resource Name | Type / Category | Primary Function in Research | Relevant Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Comprehensive Database | Provides a vast, multi-platform collection of genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data from over 20,000 cancer and normal samples, serving as a benchmark for model development and validation. | [25] |

| AACR Project GENIE | International Registry | An open-source cancer registry of real-world clinical genomic data from multiple institutions, enabling the development of tools like OncoChat on large, clinically heterogeneous datasets. | [26] |

| PyRadiomics | Software Platform | A flexible open-source platform for the extraction of a large set of handcrafted radiomics features from medical images, standardizing quantitative imaging analysis. | [23] |

| UK Biobank (UKBB) | Biobank / Cohort | A large-scale prospective cohort with deep genetic, phenotypic, and health record data, invaluable for longitudinal studies and external model validation. | [28] [29] |

| ClinVar | Clinical Genomics Database | A public archive of reports detailing the relationships between human genetic variations and phenotypic support, used for interpreting variant pathogenicity. | [24] |

| COMET Framework | Computational Method | A machine learning framework that uses transfer learning from large EHR databases to improve the analysis of smaller, high-dimensional omics datasets. | [28] |

| Core Variables (~150) | Data Standardization | A harmonized list of key clinicogenomic data elements defined by experts to ensure fit-for-purpose data collection and interoperability across precision oncology studies. | [27] |

Operational Frameworks and Translational Applications in Oncology

In the evolving landscape of cancer research, computational models have emerged as indispensable tools for understanding tumor dynamics and predicting treatment outcomes. Two predominant paradigms have shaped this field: mechanistic models grounded in biological first principles and data-driven artificial intelligence (AI) approaches that identify patterns from large datasets. Mechanistic models employ mathematical formulations to represent known or hypothesized biological processes, creating dynamic simulations of tumor initiation, growth, invasion, and response to therapeutic interventions [20]. These models are characterized by their foundation in biological mechanisms, dynamic representation of tumor processes over time, and mathematical formalisms that often employ ordinary differential equations (ODEs) or partial differential equations (PDEs) to capture system dynamics [30].

In contrast, AI and machine learning approaches leverage statistical pattern recognition on vast datasets to make predictions without necessarily embodying underlying biological mechanisms [31]. While AI has demonstrated remarkable success in diagnostic imaging and pattern classification, its "black box" nature often limits biological interpretability [32]. The ultimate goal of both approaches is to enable personalized cancer therapy by predicting individual patient responses to specific treatments, potentially avoiding ineffective therapies and their associated toxicities [20]. This review systematically compares these methodological frameworks, examining their respective strengths, limitations, and emerging hybrid approaches that seek to leverage the advantages of both paradigms.

Comparative Analysis: Mechanistic Models vs. AI in Tumor Modeling

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics of mechanistic versus AI approaches in tumor modeling

| Feature | Mechanistic Models | AI/Machine Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Foundation | Biological first principles, mathematical representations of known mechanisms | Statistical pattern recognition, neural networks |

| Data Requirements | Lower volume, but requires specific parameter measurements | Very large datasets for training |

| Interpretability | High - parameters typically have biological meaning | Low - often "black box" predictions |

| Temporal Dynamics | Explicitly modeled through differential equations | Learned from longitudinal data |

| Personalization Approach | Parameter calibration using patient-specific data | Pattern matching to similar cases in training set |

| Extrapolation Capability | Strong - can predict responses outside training conditions | Limited - primarily interpolative within training distribution |

| Clinical Integration Challenges | Parameter identifiability, model complexity | Generalizability, explainability, data hunger |

Performance Comparison in Clinical Prediction Tasks

Table 2: Quantitative performance comparison across modeling approaches

| Application Context | Model Type | Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Survival Prediction (HCC) | StepCox (forward) + Ridge (AI) | Concordance Index | 0.68 (training), 0.65 (validation) | [11] |

| Immunotherapy Response (NSCLC) | MUSK (Multimodal AI) | Prediction Accuracy | 77% | [33] |

| Immunotherapy Response (NSCLC) | PD-L1 biomarker (Standard) | Prediction Accuracy | 61% | [33] |

| Brain Tumor Segmentation | CNN-based AI | Diagnostic accuracy | Varies by architecture | [32] |

| Melanoma Recurrence Prediction | MUSK (Multimodal AI) | Prediction Accuracy | 83% | [33] |

| Tumor Growth Prediction | ODE-based mechanistic | Spatial accuracy | Hausdorff Distance metrics | [34] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

ODE-Based Mechanistic Modeling of Tumor Growth

Mechanistic models of tumor growth typically employ ordinary differential equations to capture population dynamics of cancer cells and their interactions with treatments. The fundamental experimental protocol involves:

Model Formulation: Researchers define the biological system using ODEs that represent tumor cell proliferation, death, and interaction with therapies. For instance, the exponential growth model is formulated as:

dA/dt = λA

where A represents tumor size and λ is the net growth rate [30]. More sophisticated models incorporate treatment effects, such as radiotherapy response models that partition tumor cells into surviving (A~l~) and dying (A~d~) fractions post-treatment [34]:

A~l~(t~RTstart~) = S · A(t~RTstart~)

A~d~(t~RTstart~) = (1 - S) · A(t~RTstart~)

Parameter Estimation: Using longitudinal patient data (often from medical imaging), researchers calibrate model parameters to individual patients. This typically involves optimization algorithms to minimize the difference between model predictions and observed tumor measurements [30].

Validation: The calibrated model is used to predict future tumor states, which are compared against actual follow-up measurements to assess predictive accuracy. Performance metrics may include Hausdorff Distance for spatial predictions or concordance indices for survival outcomes [34].

AI Model Training and Validation Protocols

AI approaches follow distinct experimental protocols centered on data preparation and model training:

Data Curation: Large datasets comprising medical images, clinical notes, molecular data, and outcome measures are assembled. For example, the MUSK model was trained on 50 million medical images and over 1 billion pathology-related texts [33].

Model Architecture Selection: Researchers choose appropriate neural network architectures (CNNs for images, transformers for multimodal data, etc.) based on the prediction task [32].

Training and Fine-tuning: Models are trained on labeled data, with careful separation of training, validation, and test sets to prevent overfitting. Foundation models like MUSK employ pretraining on broad datasets followed by task-specific fine-tuning [33].

Performance Assessment: Models are evaluated using metrics appropriate to the clinical question (e.g., AUC-ROC for classification tasks, C-index for survival prediction, accuracy for response prediction) [11] [33].

Hybrid Approaches: Integrating Mechanistic and AI Frameworks

Mechanistic Learning with Guided Diffusion Models

Recent research has explored hybrid frameworks that combine the strengths of both approaches. One promising methodology integrates mechanistic ODE models with guided denoising diffusion implicit models (DDIM) for spatio-temporal prediction of brain tumor growth [34].

In this approach, a mechanistic ODE model first captures temporal tumor dynamics and estimates future tumor burden. These estimates then condition a gradient-guided DDIM, enabling synthetic MRI generation that aligns with both predicted growth and patient anatomy. The experimental workflow proceeds as follows:

- Mechanistic Modeling: A compartmental ODE model simulates tumor growth dynamics, incorporating radiotherapy effects when applicable

- Tumor Burden Prediction: The model generates quantitative estimates of future tumor size

- Image Synthesis: A guided diffusion model generates synthetic follow-up MRIs that reflect the predicted tumor burden while maintaining anatomical realism

This hybrid approach addresses a key limitation of pure mechanistic models—their compression of spatial complexity—while providing the biological grounding that pure AI approaches lack [34]. The framework demonstrates particular utility in data-scarce scenarios, such as modeling rare cancers where large training datasets are unavailable.

Multimodal Data Integration Frameworks

Another hybrid approach leverages AI's strength in processing diverse data types while maintaining mechanistic interpretability. The MUSK model exemplifies this strategy by integrating pathology images, clinical notes, and molecular data to predict cancer prognoses and treatment responses [33].

This model architecture employs transformer networks capable of processing both visual and language-based information, creating a unified representation that captures complementary information across data modalities. The model demonstrated superior performance compared to single-modality approaches across multiple cancer types, highlighting the value of integrated data analysis [33].

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for tumor modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Modeling Frameworks | ODE systems (Exponential, Logistic, Gompertz) [30] | Representing intrinsic tumor growth dynamics |

| Medical Imaging Data | MRI (T1, T2, T1-CE, FLAIR sequences) [32] [34] | Model initialization and validation |

| Specialized Imaging Techniques | DCE-MRI, DW-MRI, PET with various tracers [20] | Measuring cellularity, perfusion, hypoxia, metabolism |

| Computational Tools | STRIKE-GOLDD toolbox [30] | Structural identifiability and observability analysis |

| AI Architectures | CNNs, Transformers, DDIM [32] [34] [33] | Image analysis, multimodal learning, synthetic data generation |

| Fluorescent Protein Tags | GFP, RFP variants [35] | In vivo cell tracking and visualization of metastasis |

| Molecular Data Sources | Genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic data [36] | Model personalization and biomarker discovery |

Critical Methodological Considerations

Structural Identifiability and Observability Analysis

A fundamental challenge in mechanistic modeling is ensuring that model parameters can be reliably estimated from available data. Structural identifiability analysis determines whether it is theoretically possible to uniquely determine parameter values from ideal noise-free data, while observability analysis assesses the ability to infer internal state variables from output measurements [30].

Recent research has systematically analyzed these properties for 20 published tumor growth models, revealing that many models face identifiability issues that can compromise their predictive accuracy [30]. This highlights the importance of conducting such analyses during model development and selecting models with appropriate identifiability properties for specific applications.

Data Requirements and Domain Adaptation

Both mechanistic and AI approaches face data-related challenges. Mechanistic models require specific parameter measurements that may be difficult to obtain in clinical settings, while AI models demand large, diverse datasets that adequately represent the patient population [20].

Domain adaptation presents particular challenges, as models trained on data from one institution may perform poorly on data from another due to differences in imaging protocols, staining techniques, or patient populations [32] [20]. Emerging approaches such as federated learning and domain-adversarial training aim to address these limitations but remain active research areas.

The comparison between mechanistic models and AI approaches in tumor modeling reveals complementary strengths that are increasingly being leveraged through hybrid frameworks. Mechanistic models provide biological interpretability and reliable extrapolation, while AI offers powerful pattern recognition capabilities, especially on complex, high-dimensional data. The integration of these paradigms—through approaches such as mechanistic learning with diffusion models or multimodal foundation models—represents the most promising direction for advancing predictive accuracy in clinical applications.

Future research should focus on enhancing model personalization through improved parameter estimation techniques, developing more sophisticated hybrid architectures, and addressing ethical considerations around clinical implementation. As both modeling paradigms continue to evolve, their thoughtful integration holds significant potential for transforming cancer care through truly personalized treatment optimization.

The field of tumor modeling has long been dominated by mechanistic models, which are based on predefined biological principles and mathematical representations of known cancer pathways. While these models provide valuable interpretability, they struggle to capture the full complexity and heterogeneity of cancer biology. In recent years, artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) have emerged as powerful alternatives that can learn directly from complex medical data without requiring explicit programming of all underlying biological rules [37] [38]. This paradigm shift is particularly evident in cancer diagnosis, where AI/ML systems are demonstrating remarkable capabilities in detecting malignancies across both radiological and pathological domains.

The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in their core operating principles. Mechanistic models are hypothesis-driven, built upon established knowledge of tumorigenesis, while AI/ML systems are data-driven, discovering patterns directly from imaging and molecular data [37]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of contemporary AI/ML technologies against traditional methods and each other, providing researchers and drug development professionals with experimental data to inform their diagnostic and research strategies.

Performance Comparison: AI/ML Technologies in Cancer Diagnosis

Diagnostic Accuracy Across Cancer Types

Table 1: Performance metrics of AI/ML systems across different cancer types

| Cancer Type | AI Technology | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | Comparative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Gastric Cancer | Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN) | 0.94 [39] | 0.91 [39] | 0.96-0.98 [39] | Superior to traditional CNN (Sensitivity: 0.89) [39] |

| Colorectal Cancer | CRCNet (DL model) | High (Study-specific values not reported) | High (Study-specific values not reported) | High performance across 3 datasets [10] | Achieves endoscopic detection with approximately 90% accuracy [10] |

| Breast Cancer | AI System (McKinney et al.) | Not specified | Not specified | Outperformed radiologists in clinically relevant task [10] | Generalizes from UK training data to US clinical site testing [10] |

| Lung Cancer | Convolutional Neural Network | Not specified | Not specified | 0.93 [40] | Comparable to thoracic radiologists for nodule malignancy risk assessment [40] |

| Cutaneous Melanoma | Multimodal AI (CNNs + GNNs) | High predictive accuracy | High predictive accuracy | Superior to clinical staging [41] | Particularly strong in early-stage cases where traditional stratification fails [41] |

Comparison of AI Architectures in Radiology and Pathology

Table 2: Technical comparison of major AI approaches in cancer imaging

| Characteristic | Machine Learning with Radiomics | Deep Learning | Large Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Requirement | Moderate [40] | Adequate [40] | Enormous [40] |

| Hardware Requirement | Moderate [40] | High [40] | Very High [40] |

| Feature Extraction | Predefined mathematical features [40] | Learned automatically [40] | Learned automatically [40] |

| Performance | Moderate [40] | High [40] | Very High [40] |

| Explainability | Good (Interpretable features) [40] | Poor ("Black box" characteristics) [40] | Poor (Complex decision process) [40] |

| Annotation Needs | Manual delineation required [40] | Flexible annotation [40] | Flexible annotation [40] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for AI-Assisted Early Gastric Cancer Detection

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated AI model performance for early gastric cancer (EGC) detection through rigorous methodology [39]. The protocol involved:

Data Collection and Inclusion Criteria: Researchers systematically searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure databases through January 2025 [39]. Inclusion required studies to evaluate AI accuracy in EGC diagnosis using endoscopic images/videos as input data with histopathological confirmation as the gold standard [39].

Statistical Analysis: Data extraction followed PRISMA guidelines, with two independent reviewers extracting study characteristics using a pre-designed form [39]. Sensitivity and specificity were pooled using a bivariate random effects model, with subgroup analysis by AI model type [39]. Heterogeneity was assessed using I² statistics, and publication bias was evaluated with funnel plots and Egger's test [39].

Validation Approach: The analysis included 26 studies with 43,088 patients total [39]. Performance was validated through dynamic video verification, where AI models achieved an AUC of 0.98, significantly outperforming clinician levels (AUC 0.85-0.90) [39].

Protocol for Multimodal Melanoma Metastasis Prediction

A groundbreaking 2025 study developed a multimodal AI system for predicting metastasis in cutaneous melanoma through sophisticated computational integration [41]:

Data Integration Framework: The research team employed deep learning techniques to process whole-slide histopathological images, concurrently integrating molecular data that provided gene expression patterns and protein markers [41]. Spatial analyses captured distribution and interaction networks of immune and stromal cell populations within the tumor niche [41].

Architecture Design: The system utilized convolutional neural networks (CNNs) tailored for histopathological image analysis combined with graph neural networks (GNNs) that model cellular interactions within tissue architecture [41]. CNNs identified subtle architectural cues associated with aggressive behavior, while GNNs mapped spatial proximity and communication pathways among cells [41].

Validation Methodology: Researchers assembled an extensive dataset comprising digital pathology slides and corresponding molecular data from hundreds of melanoma patients with long-term follow-up on metastatic outcomes [41]. The model underwent cross-validation and testing on independent cohorts, with particular attention to early-stage cases where traditional risk stratification is challenging [41].

Protocol for Radiomics-Based Treatment Response Prediction

Multiple studies have established standardized methodologies for developing radiomics-based predictive models:

Feature Extraction and Selection: The radiomics workflow begins with extracting predefined features from radiological images through data characterization algorithms [40]. These features capture various aspects of tumoral patterns, including intensity-based metrics, texture, shape, peritumoral characteristics, and tumor heterogeneity [40]. Feature selection refines a broad array of features to a task-specific subset to enhance predictive accuracy and minimize redundancy [40].

Model Development and Validation: Selected features are fed into machine learning models such as logistic regression or random forest for outcome prediction [40]. For example, Colen et al. created an XGBoost model with radiomics to predict pembrolizumab response in patients with advanced rare cancers, applying least absolute shrinkage and selection operator for feature selection on pretreatment CT scans [40]. The model achieved 94.7% accuracy when assessed according to RECIST criteria [40].

Multimodal Integration: Advanced approaches integrate radiomic features with complementary data types. Vanguri et al. built a multimodal deep learning model assessing immunotherapy response by integrating CT imaging, histopathologic, and genomic features from patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer [40]. This integrated approach achieved an AUC of 0.80 and outperformed unimodal models [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for AI/ML cancer diagnosis research

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (DCNN) | Advanced image analysis with hierarchical feature extraction [39] | Early gastric cancer detection in endoscopic images [39] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Modeling cellular interactions and spatial relationships within tissue [41] | Mapping immune and tumor cell communication in melanoma [41] |

| Radiomics Feature Extraction Platforms | Quantifying tumor characteristics from medical images [40] | Predicting treatment response in rare cancers [40] |

| Whole-Slide Imaging Systems | Digitizing pathology slides for computational analysis [41] | Creating digital pathology datasets for melanoma metastasis prediction [41] |

| Multimodal Data Fusion Frameworks | Integrating diverse data types (imaging, molecular, spatial) [41] | Combining histopathology with molecular profiling for metastatic risk assessment [41] |

| Interpretability Tools (Grad-CAM, SHAP) | Visualizing and explaining AI decision-making [40] | Highlighting image regions significant for thyroid nodule classification [40] |

Critical Analysis: Performance Limitations and Implementation Challenges

Despite promising performance metrics, AI/ML technologies face significant implementation challenges that must be addressed for widespread clinical adoption.

Technical and Clinical Limitations

The "black box" nature of many AI systems remains a fundamental barrier. Unlike mechanistic models with transparent reasoning processes, deep learning and large models provide limited explanation for their decision-making [42] [40]. This opacity complicates clinical trust and validation, particularly for high-stakes diagnostic decisions [42]. Techniques such as Grad-CAM and SHAP provide some interpretability by highlighting regions contributing to predictions, but full transparency remains elusive [40].

Data quality and diversity present another substantial challenge. AI models require large, high-quality datasets for training, but real-world clinical data often suffers from variability in imaging parameters, population characteristics, and annotation consistency [43] [40]. This frequently leads to performance degradation when models are applied to external datasets from diverse sources [40]. For example, while CADe systems for colorectal polyp detection demonstrate increased adenoma detection in randomized trials, they have not consistently improved identification of advanced colorectal neoplasias in screening programs [10].

Integration and Workflow Considerations

Successful implementation requires seamless integration into existing clinical workflows, which poses both technical and human-factor challenges [44] [41]. The "Third Wheel Effect" describes patient perception of AI as an unnecessary intrusion rather than a valuable addition, potentially undermining doctor-patient relationships [44]. Furthermore, inadequate communication about AI's benefits may exacerbate patient mistrust of AI-aided diagnoses [44].

Resource requirements also vary significantly between approaches. While radiomics-based machine learning has moderate data and hardware needs, deep learning requires adequate resources, and large models demand enormous computational infrastructure [40]. These practical considerations directly impact accessibility and implementation across healthcare settings with varying resources.

Future Directions and Clinical Translation

The evolving landscape of AI/ML in cancer diagnosis points toward several critical developments that will shape future research and clinical implementation.

Explainable AI and Multimodal Integration

Enhancing model interpretability remains a priority for clinical translation. Explainable AI (XAI) approaches are attracting increasing interest as mechanisms to provide patient-friendly explanations of biomedical decisions based on machine learning [44]. This transparency is particularly crucial in oncology, where diagnostic decisions carry significant psychological and emotional implications for patients [44].

Multimodal approaches that integrate diverse data types represent another promising direction. The success of systems combining histopathological images with molecular profiling and spatial data demonstrates the potential of synthesizing complementary information sources [41]. This methodology can reveal previously underappreciated tumor microenvironment components that drive cancer progression while improving predictive accuracy [41].

Validation Frameworks and Clinical Workflow Integration

Future progress requires robust validation frameworks assessing AI performance across diverse populations and clinical settings [39] [41]. Multicenter prospective validation will be essential to establish generalizability and address performance variability across different patient demographics and healthcare systems [39]. Additionally, research should focus on developing standardized protocols for data acquisition, computational infrastructure, and clinician training to bridge the gap between technological innovation and practical healthcare impact [41].

The most successful implementations will likely adopt a hybrid approach that leverages the strengths of both AI/ML and human expertise. Rather than positioning AI as a replacement for clinicians, the optimal framework integrates AI assistance within clinical decision-making processes, enhancing diagnostic accuracy while maintaining physician oversight and patient-centered care [44] [40].

The challenge of predicting patient-specific responses to cancer therapy represents a central frontier in precision oncology. In addressing this challenge, the research community has diverged into two complementary computational philosophies: mechanistic modeling and artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML) approaches. Mechanistic models are grounded in established biological principles, constructing mathematical representations of known tumor dynamics, such as cell cycle progression, drug pharmacokinetics, and tumor-immune interactions. Conversely, AI/ML models are data-driven, discovering complex patterns directly from clinical, genomic, and imaging datasets without pre-specified biological rules. This guide objectively compares the performance of representative tools from both paradigms, examining their experimental validation, methodological frameworks, and applicability to chemotherapy and immunotherapy response prediction.

AI/Machine Learning Tools for Response Prediction

AI/ML tools have demonstrated remarkable progress in predicting therapy response by leveraging large-scale multimodal patient data. The table below compares several leading AI approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of AI/ML Tools for Predicting Therapy Response

| Tool Name | Model Type | Input Data | Cancer Types Validated | Reported Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCORPIO [45] | AI (Machine Learning) | Routine blood tests, clinical data (age, sex, BMI) | 21 types (inc. melanoma, lung, bladder, liver, kidney) | 72-76% accuracy for survival prediction over 2.5 years; outperformed TMB | Uses low-cost, routine data; avoids expensive genomic tests |

| Compass [46] | AI (Foundation Model with Concept Bottleneck) | Pan-cancer transcriptomic data | 33 cancer types, validated across 7 cancers and 6 ICIs | Increased precision by 8.5%, MCC by 12.3%, AUPRC by 15.7% vs. baselines | High generalizability to unseen cancers/treatments; provides mechanistic insights |

| Lunit SCOPE IO [47] | AI (Deep Learning on Pathology Images) | Pre-treatment histology slides (H&E stains) | Colorectal cancer (pMMR mCRC), kidney cancer (ccRCC), NSCLC | Identified "inflamed" phenotypes with significantly longer PFS & OS (e.g., response rate 60.5% vs 23.2% in ccRCC) | Leverages standard pathology slides; identifies immune phenotypes |

| AI-Assisted PET Imaging [48] | AI (Radiomics/Deep Learning) | PET imaging data | Breast Cancer (NAC response) | Pooled AUC of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.77-0.84) in meta-analysis | Non-invasive; uses standard-of-care imaging |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The performance data in Table 1 is derived from rigorous experimental designs. Below are the core methodologies for the key tools.

SCORPIO Experimental Protocol [45]:

- Objective: To predict survival and tumor response following immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) treatment using only routine clinical and blood test data.

- Training Cohort: Data from ~2,000 patients treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

- Input Features: Age, sex, body mass index, and measurements from standard blood panels.

- Validation: Tested on several independent validation sets, including real-world cohorts and 10 clinical trials, totaling nearly 10,000 patients.

- Output: A prediction of likelihood of survival and tumor shrinkage.

Compass Experimental Protocol [46]:

- Objective: To build a generalizable foundation model for predicting immunotherapy response from tumor transcriptomic data.

- Training Data: 10,184 tumors across 33 cancer types.

- Model Architecture: A concept bottleneck model that encodes tumor gene expression through 44 biologically grounded immune concepts (e.g., immune cell states, signaling pathways).

- Validation: Performance was evaluated against 22 baseline methods in 16 independent clinical cohorts spanning seven cancers and six ICIs.

- Output: A response prediction, along with a "personalized response map" that links gene expression to immune concepts to explain the prediction.

Lunit SCOPE IO Experimental Protocol [47]:

- Objective: To use AI for analyzing digitized histology slides to predict response to immunotherapy.

- Input: Pre-treatment H&E-stained tissue slides are digitized into whole-slide images.

- AI Analysis: A deep learning algorithm analyzes the tumor microenvironment, quantifying and spatially characterizing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs).

- Output Classification: Tumors are classified as "inflamed" (TILs present within the tumor) or "non-inflamed" (TILs excluded). The "inflamed" phenotype is associated with a higher probability of response to ICIs.