Spatial Agent-Based Models in Oncology: Decoding Tumor Heterogeneity for Advanced Therapeutics

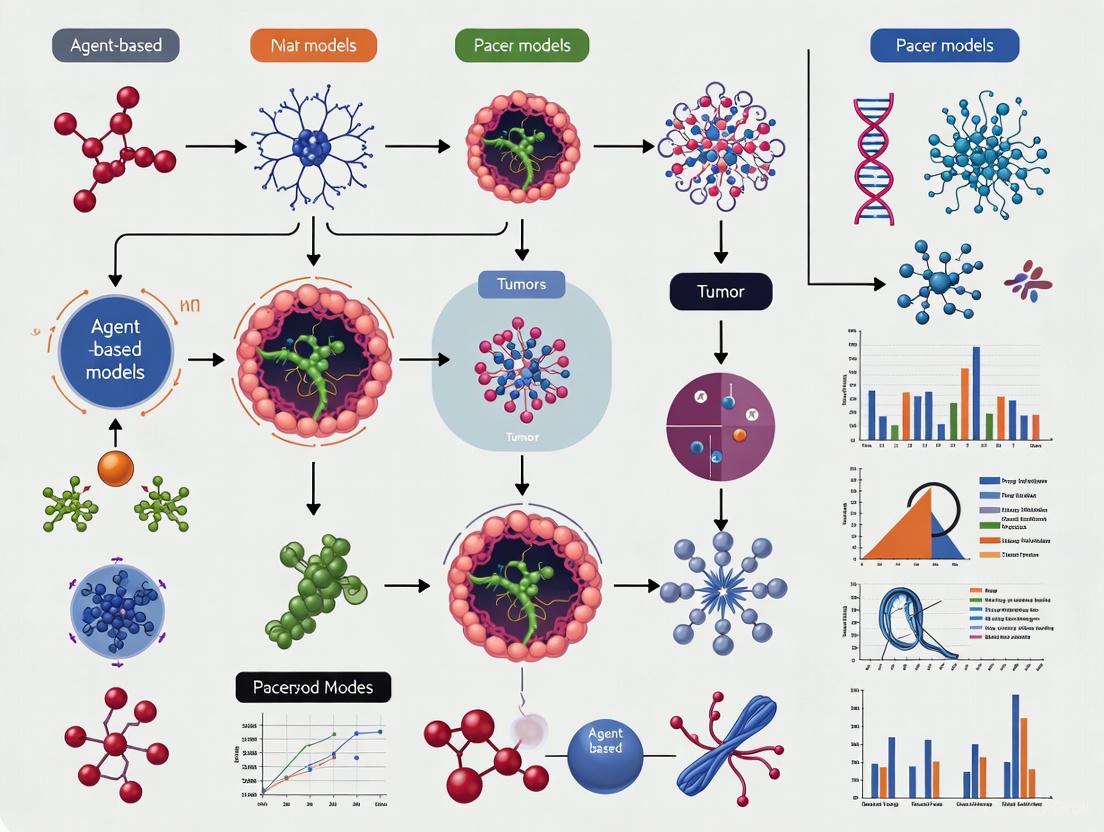

This article explores the pivotal role of Spatial Agent-Based Models (SABMs) in capturing the complex spatial and phenotypic heterogeneities within solid tumors.

Spatial Agent-Based Models in Oncology: Decoding Tumor Heterogeneity for Advanced Therapeutics

Abstract

This article explores the pivotal role of Spatial Agent-Based Models (SABMs) in capturing the complex spatial and phenotypic heterogeneities within solid tumors. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive guide from foundational principles to advanced applications. The content covers core concepts of spatial structure in tumor evolution, practical methodologies for model implementation, strategies to overcome common computational challenges, and rigorous frameworks for model validation. By synthesizing recent advances, this article demonstrates how SABMs serve as indispensable tools for making sense of complex clinical data, predicting treatment outcomes, and optimizing therapeutic strategies, ultimately bridging the gap between computational prediction and clinical translation in precision oncology.

The Spatial Dimension: Why Location Matters in Tumor Evolution

Spatial Agent-Based Models (SABMs) are computational approaches for investigating the evolution of solid tumours by simulating autonomous, interacting "agents" – typically individual cells – within a spatially explicit microenvironment [1]. These models are uniquely powerful for capturing how localized cell-cell interactions and microenvironmental heterogeneity influence fundamental cancer processes, including tumour development, the emergence of treatment resistance, and response to therapy [1] [2]. As spatial genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic technologies advance, SABMs are becoming increasingly critical for interpreting complex clinical data, predicting outcomes, and optimizing treatment strategies [1].

Core Principles and Definitions

An Agent is an autonomous, discrete entity with defined properties and behavioral rules. In cancer SABMs, this is most often a cell (e.g., cancer cell, immune cell) [1]. The Environment is the spatial domain in which agents interact, which can include factors like nutrient gradients, extracellular matrix density, and chemical signals [3]. Spatial Rules govern agent behaviors—such as division, death, and movement—based on their local microenvironment and the states of nearby agents [1].

A common foundational SABM is the Eden growth model, a stochastic cellular automaton typically implemented on a 2D or 3D grid. It simulates tumour growth where new cells are added to the surface of a cell cluster, self-organizing into a structure with a non-trivial surface [1]. The model's behavior can be fine-tuned using different update rules (e.g., cell-focussed, available site-focussed) which influence the roughness of the tumour surface [1].

Quantitative Parameters for Model Initialization

The following parameters are essential for initializing a basic tumour growth SABM, drawn from established modeling platforms and studies.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters for a Basic Tumour SABM

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Typical Value / Range | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initialization | Initial number of cancer cells | 2,500 - 17,000+ [2] | Affects model's ability to capture emergent dynamics (e.g., immune response) [2]. |

| Grid size (2D) | 100x100 to 500x500+ sites | Determines spatial scale and computational load. | |

| Cellular Rates | Probability of cell division | 0.1 - 0.5 per time step | Core driver of tumour expansion. |

| Probability of cell death | 0.01 - 0.1 per time step | Creates space for clonal mixing and selection [1]. | |

| Spatial Constraints | Neighborhood definition | Von Neumann (4 neighbors) or Moore (8 neighbors) [1] | Defines local interaction space for a cell. |

| Carrying capacity (local) | 1 cell per grid site | Simulates physical space limitation and contact inhibition. |

Detailed Protocol: Building a Basic Tumour Growth SABM

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a basic 2D spatial agent-based model of avascular tumour growth.

Step-by-Step Model Workflow

Step 1: Environment Setup

- Initialize a 2D grid (e.g., 200x200 sites), where each site can be occupied by one cell or be empty.

- Define a neighborhood for each cell (e.g., Von Neumann: up, down, left, right) [1].

Step 2: Agent Initialization

- Place a small cluster of proliferative cancer cells (e.g., 10 cells) at the center of the grid.

- Assign each cell a unique ID and initialize its state (e.g.,

cell_type: "cancer",alive: True).

Step 3: Simulation Loop (Asynchronous Updating) For each simulation time step: 1. Shuffle: Create a randomized list of all currently alive cells. This ensures unbiased asynchronous updating [1]. 2. Iterate: For each cell in the shuffled list: - Check Neighborhood: Assess the number and type of cells in its immediate neighborhood. - Execute Rules: - Division: If the cell is a cancer cell and has an empty neighboring site, it may divide with a defined probability (e.g., 0.2), placing a new daughter cell in the empty site. - Death: The cell may undergo apoptosis with a lower probability (e.g., 0.05), freeing its site. 3. Update Grid: Synchronize the grid state after all agent actions are processed.

Step 4: Data Collection & Visualization

- At regular intervals, record metrics: total cell count, tumour radius, and spatial distribution of cells.

- Visualize the grid, using colors to represent different cell types or states.

Workflow Visualization

Advanced Application: Integrating the Tumour Microenvironment (TME)

To move beyond basic growth models, SABMs can incorporate critical elements of the TME. A key application is modeling the response to immunotherapies, such as oncolytic viruses (OVs) and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) [2].

Advanced Protocol: Modeling Immunotherapy in Glioblastoma

Step 1: Introduce Agent Diversity. Populate the model with additional agent types beyond cancer cells, such as:

- CD8+ T cells: Capable of killing cancer cells.

- Macrophages: Can have pro- or anti-tumour phenotypes.

- Stromal cells: Contribute to physical structure and signaling.

Step 2: Implement Diffusible Factors. Use partial differential equations (PDEs) coupled to the ABM to simulate:

- Oxygen and Nutrients: Create heterogeneous growth conditions.

- Chemoattractants: Guide immune cell migration.

- Cytokines: Modulate agent behaviors and cell states [3] [2].

Step 3: Define Treatment Mechanisms.

- Oncolytic Virus (OV): An OV agent can infect and lyse cancer cells. Upon lysis, it releases virions and tumor antigens, the latter of which can help activate nearby T cells [2].

- Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor (ICI): Simulate an ICI by modifying the rules of interaction between T cells and cancer cells. For example, an ICI can increase the probability that a T cell successfully kills a cancer cell upon contact [2].

Step 4: Initialize with Patient Data. For patient-specific predictions, initialize the spatial distribution and proportions of cell types using data from technologies like Imaging Mass Cytometry (IMC) [2]. Studies show that models initialized with a sufficient number of cells (e.g., >10,000) are necessary to adequately capture the dynamics of the adaptive immune response [2].

Signaling Pathways in Immunotherapy

The following diagram illustrates the core agent interactions and signaling pathways activated by combination OV and ICI therapy within the SABM.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools for SABM Research

| Item Name | Type/Category | Function in SABM Research |

|---|---|---|

| Imaging Mass Cytometry (IMC) [2] | Spatial Profiling Technology | Provides high-plex, single-cell spatial protein data to initialize and validate model parameters and cell distributions. |

| Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Assays [4] | Liquid Biopsy | Enables monitoring of clonal evolution and treatment resistance during therapy, providing dynamic data for model calibration. |

| Recombinant Human Hyaluronidase PH20 [5] | Drug Delivery Agent | Component of subcutaneous drug delivery systems (e.g., for amivantamab); models can simulate its effect on drug penetration. |

| Pasritamig (JNJ-78278343) [5] | Bispecific T-cell Engager | A first-in-class therapeutic targeting KLK2 in prostate cancer; serves as a prototype for modeling bispecific antibody mechanisms. |

| demon-warlock framework [1] | Computational Platform | An example of a state-of-the-art SABM framework used for simulating tumour evolution and treatment. |

| MetaCancer Framework [3] | AI/ML Model | A deep learning model that predicts metastatic status; can be integrated with SABMs for multi-scale analysis. |

The growth and progression of tumors are complex processes mediated not solely by cancer cells themselves, but through intricate, mutual interactions between cancer cells and the surrounding stroma that forms the tumor microenvironment (TME) [6]. This environment includes diverse cell types—such as fibroblasts and immune cells—as well as acellular components like the extracellular matrix [6]. Within this ecosystem, direct intercellular communications play pivotal roles in regulating tumor behavior, influencing whether a tumor is suppressed or promoted [6]. Understanding these localized interactions is crucial, as they can drive the emergence of global tumor properties, including metastatic capability and therapy resistance [6] [7].

Agent-based models (ABMs) have gained popularity in cancer research for their ability to model detailed phenotypic and spatial heterogeneity, thereby better reflecting the complexity seen in vivo compared to non-spatial models like Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) [8]. These models are particularly valuable for quantifying the influence of spatially-dependent characteristics of tumor-immune dynamics and simulating the cellular interactions that underpin treatment responses [8].

Key Mechanisms of Cell-Cell Communication

Direct cell-to-cell contact between cancer cells and stromal cells can crucially affect the biological behavior of cancer cells, initiating signaling cascades that regulate tumor progression [6].

EMP1-Mediated Pro-Metastatic Signaling

Epithelial membrane protein 1 (EMP1), a member of the tetraspanin superfamily, is upregulated in cancer cells upon direct association with stromal cells [6]. This protein promotes tumor cell migration and metastasis via activation of the small GTPase Rac1 [6]. The intracellular domain of EMP1 directly binds to copine-III, triggering a signaling cascade mediated by the protein tyrosine kinase Src and the Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factor Vav2, ultimately activating Rac1 to enhance cell migration and invasiveness [6]. In prostate cancer models, LNCaP cells expressing EMP1 exhibited enhanced lymph node and lung metastasis without affecting primary tumor growth, highlighting its specific role in metastatic dissemination [6].

Stomatin-Mediated Tumor Suppression

Stomatin, a member of the SPFH superfamily, is another protein upregulated through cancer-stroma contact [6]. In contrast to EMP1, stomatin acts as a tumor suppressor by strongly suppressing cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis in cancer cells [6]. It achieves this by inhibiting the Akt signaling pathway, which is crucial for cell survival and proliferation [6]. Stomatin binds to phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDPK1) and inhibits the formation of its stabilizing complex with heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), leading to the suppression of this key pro-survival pathway [6].

Table 1: Proteins Regulated by Direct Cell-Cell Contact and Their Functions in Cancer

| Protein | Family | Expression Trigger | Downstream Pathway | Net Effect on Tumor Progression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMP1 | Tetraspanin (PMP22 family) | Direct association with prostate stromal cells | Activates Src/Vav2/Rac1 signaling | ↑ Migration & Metastasis [6] |

| Stomatin | SPFH superfamily | Direct association with prostate stromal cells | Inhibits PDPK1/Akt signaling | ↓ Proliferation & ↑ Apoptosis [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Studying Cell-Cell Interactions

In Vitro Coculture System for Identifying Contact-Mediated Gene Expression

Purpose: To identify genes upregulated in cancer cells specifically through direct cell-to-cell contact with stromal cells, while limiting the effects of soluble factors [6].

Materials:

- Cancer Cells: Prostate cancer LNCaP cell line.

- Stromal Cells: Primary human prostate stroma (PrS).

- Equipment: Standard cell culture equipment, facilities for RNA sequencing.

Procedure:

- Culture LNCaP cells and primary human prostate stromal (PrS) cells separately until 70-80% confluent.

- Coculture LNCaP cells with PrS cells in a direct contact system. The system should be designed to minimize the influence of soluble factors secreted by either cell type.

- After a predetermined coculture period, separate the cancer cells from the stromal cells.

- Extract total RNA from the LNCaP cells.

- Perform RNA sequencing and analyze the data to identify genes with significantly upregulated expression in cocultured LNCaP cells compared to LNCaP cells cultured alone.

- Validate the function of identified genes (e.g., EMP1, stomatin) through gain-of-function and loss-of-function experiments in relevant cancer cell lines.

Protocol for Analyzing Tumor-Wide Communication from scRNAseq Data

Purpose: To decipher population-level signaling between cancer and non-cancer cell populations within tumors using single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) data, accounting for both cellular composition and phenotypic heterogeneity [7].

Materials:

- Patient Samples: Serial tumor biopsies (e.g., from breast cancer patients pre-, during, and post-treatment).

- Reagents: Single-cell RNA sequencing reagents (e.g., 10X Genomics).

- Software Tools: Cell type annotation tools (SingleR, InferCNV), immune subtyping tools (ImmClassifier), and cell-cell interaction analysis methods.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation and Sequencing:

- Obtain high-quality single-cell suspensions from patient tumor biopsies.

- Perform scRNAseq using a platform like 10X Genomics to generate transcriptional profiles of all cells in the tumor ecosystem.

Cell Type Annotation and Verification:

- Identify broad cell types (epithelial, myeloid, T cells, fibroblasts, etc.) using a reference-based tool like SingleR [7].

- Identify cancer cells by detecting pronounced copy number variations using InferCNV [7].

- Verify annotations by assessing cell type-specific marker gene expression and via dimensionality reduction plots (UMAP/TSNE).

- Obtain granular immune subtype annotations using ImmClassifier [7].

Ligand-Receptor Interaction Analysis:

- Apply a population-level signaling analysis method (e.g., an extended expression product method) to the scRNAseq data [7].

- Use ligand and receptor gene expression profiles from sending and receiving cells to infer communication strengths between different cell populations [7].

- Analyze how these communication networks differ between clinical groups (e.g., treatment-sensitive vs. treatment-resistant tumors).

Quantitative Data and Agent-Based Modeling

Key Quantitative Findings in Tumor-Immune Interactions

Recent research on high-risk ER+ breast cancer patients treated with CDK4/6 inhibitors (e.g., ribociclib) has yielded quantitative insights into how cellular interactions underpin treatment resistance [7].

Table 2: Cellular Composition and Communication Findings in CDK4/6 Inhibitor Resistant vs. Sensitive Tumors

| Analysis Aspect | Resistant (Growing) Tumors | Sensitive (Shrinking) Tumors |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Composition | Cancer/stromal dominated [7] | Immune-enriched [7] |

| Key Cancer Signaling | Upregulated cytokines stimulating immune-suppressive myeloid differentiation [7] | Not detailed in available results |

| Myeloid-T cell Crosstalk | Reduced via IL-15/18 signaling [7] | Present |

| T cell Status | Diminished activation and recruitment [7] | Activated and recruited |

Integrating Experimental Data into Agent-Based Models

Agent-based models (ABMs) provide a computational framework to simulate the complex, spatially-structured interactions within the TME. The experimental data and mechanisms described above can be directly incorporated into an ABM.

Modeling Steps:

- Define Agent Types and Rules: Create agents representing cancer cells, T cells, myeloid cells, and fibroblasts. Program them with rules derived from experimental findings. For example:

- A cancer cell agent that, upon direct contact with a stromal fibroblast agent, upregulates EMP1 expression, increasing its migration probability.

- A myeloid cell agent that, upon receiving signals from a cancer cell agent, adopts an immune-suppressive phenotype.

- A T cell agent whose activation state is inhibited by immune-suppressive myeloid agents, reducing its cancer cell killing efficacy.

Incorporate Spatial Heterogeneity: Model the TME as a 2D or 3D grid where agents occupy space and interact with neighbors, simulating direct cell-cell contact.

Simulate Therapeutic Interventions: Introduce a "CDK4/6 inhibitor" event that reduces the proliferation probability of cancer cell agents. Observe how pre-existing communication networks (e.g., low T-cell recruitment) lead to regrowth, mimicking clinical resistance [7] [8].

Model Validation: Calibrate the model so that simulation outcomes (e.g., tumor shrinkage vs. growth) match the clinical and biological data observed in patient cohorts [7].

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: EMP1-mediated pro-metastatic signaling pathway.

Diagram 2: Stomatin-mediated tumor-suppressive signaling pathway.

Diagram 3: Workflow for building an agent-based model from scRNAseq data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Studying Cell-Cell Interactions in the TME

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Coculture Systems | Models direct cell-cell contact while limiting soluble factor effects. | Identifying contact-mediated gene upregulation (e.g., EMP1, stomatin) [6]. |

| Primary Human Stromal Cells | Provides physiologically relevant stromal partners for coculture. | Studying the specific effects of human prostate stroma on prostate cancer cells [6]. |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNAseq) | Profiles transcriptional states of all cells in a tumor ecosystem. | Deciphering cell type composition, ligand-receptor networks, and heterogeneity [7]. |

| Cell Type Annotation Algorithms (SingleR, InferCNV) | Identifies and classifies cell types from scRNAseq data. | Distinguishing cancer cells from non-malignant cells and annotating immune subsets [7]. |

| Ligand-Receptor Analysis Tools | Infers cell-cell communication from scRNAseq expression data. | Quantifying signaling strengths between different cell populations in a tumor [7]. |

| Agent-Based Modeling Platforms | Computationally simulates spatial interactions between heterogeneous cell agents. | Testing how localized cell-cell interactions give rise to global tumor dynamics and treatment response [8]. |

Spatial structure is a fundamental determinant of evolutionary dynamics in solid tumours, directly shaping the balance between selection, genetic drift, and gene flow. The spatial arrangement of cells dictates the nature of their local interactions, which in turn influences clonal competition, the emergence of treatment resistance, and intratumoural heterogeneity [1]. Agent-based models (ABMs) have emerged as indispensable tools for investigating these spatial relationships, enabling researchers to simulate how autonomous, interacting cells behave within the complex geometry of the tumour microenvironment [1]. The critical importance of accurately representing spatial structure is underscored by evidence that when models fail to capture a biological system's true spatial architecture, their predictions and inferences may become highly unreliable [1]. This application note provides a structured framework for employing spatial ABMs to investigate evolutionary dynamics in cancer research, complete with experimental protocols, quantitative benchmarks, and essential research tools.

Theoretical Foundation: Spatial Evolutionary Dynamics

Spatial structure regulates evolutionary processes through distinct mechanistic pathways:

- Selection: Localized cell-cell interactions create microenvironments that impose differential fitness constraints, allowing advantageous clones to expand through spatial competition rather than global fitness advantages [1] [9].

- Genetic Drift: In structured populations, stochastic fluctuations in clone frequencies occur more readily within isolated subpopulations or at the expanding tumour frontier, where effective population sizes are small [1].

- Gene Flow: The physical displacement of cells through division and migration facilitates the spread of genetic variants, but this movement is constrained by physical barriers and population density [1].

Table 1: Evolutionary Forces in Spatial Contexts

| Evolutionary Force | Spatial Influence Mechanism | Impact on Tumour Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Selection | Local competition for space and resources | Drives adaptation to microenvironmental niches; promotes treatment resistance |

| Genetic Drift | Finite local population sizes in structured habitats | Increases stochastic extinction of clones; enhances intra-tumour heterogeneity |

| Gene Flow | Physical constraints on cell dispersal and division | Limits or facilitates spread of beneficial mutations; creates spatial mixing patterns |

Computational Modeling Approaches

Agent-Based Model Implementation Protocol

Purpose: To establish a spatial computational model that captures evolutionary dynamics through local cell-cell interactions.

Materials:

- Computational environment (Python, R, or C++)

- High-performance computing resources for large-scale simulations

- Visualization software for spatial data analysis

Procedure:

Define Spatial Domain:

- Implement a 2D or 3D grid with specified dimensions (e.g., 1000×1000 sites for 2D simulations)

- Choose neighborhood topology: von Neumann (4 neighbors in 2D) or Moore (8 neighbors in 2D) [1]

Initialize Agent Population:

- Seed initial tumor cells at grid center or specified locations

- Assign agent states: proliferation capacity, death probability, mutation status [1]

Implement Update Rules:

- Use asynchronous updating to avoid conflicts

- For each time step: a. Randomly select an agent b. Assess local neighborhood conditions c. Execute probabilistic rules for division, death, or migration [1]

- Division rules: Require empty adjacent site; implement "budging" or replacement if no space available [1]

- Death rules: Remove cell with probability pdeath, creating empty site

Incorporate Evolutionary Dynamics:

- Introduce stochastic mutation events during division (e.g., 10-6 to 10-9 per gene per division)

- Assign fitness effects to mutations (selective advantage s = 0.01-0.1)

- Track clonal lineages through spatial coordinates and inheritance

Simulation Execution:

- Run simulations for 10,000-100,000 time steps or until population reaches carrying capacity

- Execute multiple replicates (n≥20) to account for stochasticity

Data Collection:

- Record spatial coordinates of all cells and their genotypes at regular intervals

- Calculate diversity metrics (Shannon index, Simpson diversity)

- Map spatial distribution of clones and measure mixing indices

Advanced Hybrid Modeling Framework

For investigations requiring multiscale resolution, hybrid frameworks couple agent-based models with continuum approaches:

Protocol: PDE-ABM Integration

Continuum Component:

- Implement reaction-diffusion equations for nutrient (oxygen), drug, and growth factor concentrations

- Solve using finite difference or finite element methods on spatial grid [10]

Discrete Component:

- Model individual cells as agents responding to local continuum fields

- Implement phenotype switching via exact Gillespie algorithm for stochastic transitions [10]

Bidirectional Coupling:

- Agent behaviors depend on local concentration fields

- Agent activities (e.g., oxygen consumption) modify continuum fields

- Update coupling at each time step [10]

Table 2: Hybrid Model Parameters for Angiogenesis-Regulated Resistance

| Model Component | Parameter | Symbol | Typical Value/Range | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Field | Diffusion coefficient | Do | 10-5 cm²/s | Determines oxygen penetration depth |

| Consumption rate | λo | 0.1-1.0 min⁻¹ | Metabolic activity of tumour cells | |

| TAF Field | Chemotaxis coefficient | χ0 | 0.1-0.5 cm²/s | Endothelial cell migration strength |

| Degradation rate | α | 0.01-0.1 min⁻¹ | Stability of angiogenic signals | |

| Cell Agents | Phenotype switch rate | kswitch | 10-4-10-6 h⁻¹ | Frequency of resistance acquisition |

| Division time | Tdiv | 12-48 h | Population growth rate |

Experimental Validation Protocols

Quantifying Spatial Heterogeneity in Clinical Specimens

Purpose: To empirically measure intra-tumoral spatial heterogeneity for model parameterization and validation.

Materials:

- Multiplex immunofluorescence (MxIF) imaging system

- Whole-mount histopathology equipment

- Automated image analysis software

- Fresh tumour tissue specimens (e.g., breast cancer lumpectomy samples) [11]

Procedure:

Tissue Processing:

- Collect fresh tumour specimens immediately after surgical resection

- Process using whole-mount techniques to preserve spatial architecture [11]

- Section into 4-5μm slices for MxIF analysis

Multiplex Immunofluorescence:

- Perform sequential staining cycles for biomarkers of interest: a. ER, PR, HER2, Ki67 for molecular subtyping b. CD3, CD8, CD68 for immune contexture c. Cytokeratin for epithelial cells [11]

- Image using automated microscopy at 20× magnification

- Generate high-dimensional protein expression data at single-cell resolution

Spatial Analysis:

- Segment individual cells and assign spatial coordinates

- Quantify biomarker expression variations between tumour regions

- Classify immune niche phenotypes through image patch analysis [11]

- Calculate diversity indices across spatial scales

Data Integration:

- Compare regional molecular subtype classifications

- Correlate spatial heterogeneity measures with clinical outcomes

- Use spatial statistics to inform ABM parameters

In Vitro Validation of Spatial Treatment Responses

Purpose: To empirically test model predictions about spatial factors in treatment responses using 3D cell culture systems.

Materials:

- FaDu epithelial cell line or other relevant cancer models

- ATR inhibitor (ceralasertib) and PARP inhibitor (olaparib) [9]

- Confocal microscopy with time-lapse capability

- Fluorescent labeling reagents for lineage tracking

Procedure:

Spatial Configuration Setup:

- Establish co-cultures with defined initial spatial arrangements of sensitive and resistant cells

- Vary initial fractions of drug-resistant cells (1%-10%)

- Implement 3D spheroid systems with controlled initial geometry

Treatment Application:

- Apply monotherapies and combination treatments

- Test multiple dosing schedules (continuous, adaptive, bipolar) [12]

- Monitor response dynamics using time-lapse microscopy

Spatial Tracking:

- Track spatial configuration of resistant subclones within spheroids using confocal microscopy [12]

- Quantify changes in cell-to-cell interaction patterns over time

- Measure migration and invasion distances of specific clones

Data Correlation:

- Compare experimental outcomes with ABM predictions

- Refine model parameters based on observed spatial dynamics

- Validate evolutionary trajectory forecasts

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Spatial Evolutionary Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| demon-warlock framework [1] | Spatial ABM platform | Simulating tumour evolution with local cell-cell interactions |

| SLiM 3 [13] | Stochastic evolutionary modeling | Incorporating genetic drift and complex population structures |

| Multiplex Immunofluorescence [11] | High-dimensional protein mapping | Quantifying spatial heterogeneity in clinical specimens |

| Hybrid PDE-ABM framework [10] | Multiscale modeling | Coupling vascular remodeling with resistance evolution |

| Mozzie modeling tool [13] | Spatial dispersal simulation | Analyzing spread dynamics across heterogeneous landscapes |

Application Case Studies

Evolutionary Therapy Optimization

Spatial ABMs have demonstrated particular utility in optimizing evolutionary therapy strategies:

Protocol: Adaptive Therapy Scheduling

Model Setup:

- Initialize tumour with mixed sensitive/resistant populations

- Parameterize growth and competition dynamics from experimental data [9]

Treatment Simulation:

- Compare continuous vs. adaptive dosing schedules

- For adaptive therapy: administer treatment until tumour burden decreases by predetermined percentage (e.g., 50%), then pause until regrowth reaches threshold [12]

Spatial Considerations:

- Account for differences in 2D vs. 3D spatial constraints

- Model resource competition and local migration [12]

- Incorporate spatial heterogeneity in drug delivery

Outcome Assessment:

- Measure time to treatment failure across strategies

- Quanticate preservation of treatment-sensitive populations

- Analyze spatial patterns of resistance emergence

Angiogenesis-Regulated Resistance

The bidirectional coupling between hypoxia-driven angiogenesis and resistance evolution can be investigated using hybrid PDE-ABM frameworks:

Key Findings:

- Hypoxia gradients create spatial heterogeneity in selection pressures

- Angiogenic remodeling alters drug delivery patterns, creating sanctuaries for resistant clones [10]

- Vascular normalization strategies can modulate evolutionary trajectories

Spatial structure serves as a fundamental determinant of evolutionary dynamics in cancer, directly influencing the balance between selection, drift, and gene flow. The agent-based modeling protocols outlined herein provide researchers with robust methodologies for investigating these relationships across multiple scales. When parameterized with empirical data from spatial profiling technologies and validated through controlled experiments, these computational approaches offer powerful predictive tools for understanding treatment resistance and optimizing therapeutic strategies. The integration of spatial explicit modeling with high-resolution experimental data represents a promising pathway for advancing personalized cancer therapy.

The progression from simple, non-spatial models of tumor growth to sophisticated, spatially-resolved computational frameworks represents a paradigm shift in mathematical oncology. Traditional models, such as those based on ordinary differential equations (ODEs), simulate cellular populations as well-mixed systems, averaging dynamics across the entire population without accounting for spatial organization [8]. While computationally efficient for modeling temporal changes in bulk tumor composition, these approaches fundamentally cannot capture the spatial heterogeneity and microenvironmental interactions now recognized as critical drivers of therapeutic resistance and disease progression [8] [14].

Agent-based models (ABMs) have emerged as powerful tools that address this spatial imperative by simulating individual cells ("agents") within a defined spatial landscape, enabling researchers to investigate how complex tumor behaviors emerge from simple rules governing cell-cell and cell-environment interactions [14] [15]. This Application Note examines the spectrum of modeling approaches, with particular focus on protocol implementation for ABMs that capture the spatial heterogeneities central to contemporary tumor research and therapeutic development.

Modeling Approaches: From Continuum to Discrete Frameworks

Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) Models

ODE models represent tumor-immune dynamics through equations that describe the time-dependent evolution of cellular populations, treating these populations as continuous and homogeneous.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of ODE versus Agent-Based Modeling Approaches

| Feature | ODE Models | Agent-Based Models |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | None (well-mixed assumption) | Explicit (lattice or off-lattice) |

| Representation Scale | Population-level | Individual cell-level |

| Stochasticity | Typically deterministic | Inherently stochastic |

| Computational Demand | Generally low | Moderate to high |

| Key Strength | Rapid simulation of temporal dynamics | Captures emergence and spatial heterogeneity |

| Implementation Example | Lotka-Volterra type predator-prey models for tumor-immune interactions | PhysiCell, Hybrid Automata Library for simulating individual cell behaviors |

The primary limitation of ODE models is their inability to simulate spatial processes such as the formation of tumor cell clusters, spatial variations in immune infiltration, or the role of physical barriers in treatment delivery [8]. These spatial factors are now understood to be critical determinants of treatment response, particularly for immunotherapies [8].

Agent-Based Models (ABMs) for Spatial Heterogeneity

ABMs address ODE limitations by representing individual cells as autonomous agents that interact with neighbors and their local environment according to predefined rules [14] [15]. This bottom-up approach enables the emergence of complex system behaviors—such as tumor segmentation into phenotypically distinct regions and the development of resistance niches—from relatively simple individual-level rules [8] [16].

Figure 1: Spectrum of tumor modeling approaches, progressing from non-spatial ODE models to spatially explicit agent-based frameworks and culminating in hybrid multi-scale models.

Application Note: Implementing a Prostate Cancer Agent-Based Model

Model Conceptualization and Design

We detail the implementation of a prostate cancer-specific ABM (PCABM) that exemplifies the application of spatial modeling to investigate therapy resistance [16]. This model was developed to understand how interactions between different cell types in the prostate tumor microenvironment (TME) contribute to the development of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) following androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).

Base Model Assumptions and Cell Types:

- Agents represent: PCa cells, fibroblasts, M1-like (pro-inflammatory) macrophages, M2-like (pro-tumor) macrophages

- Spatial configuration: 2D grid with random initial cell distribution

- Temporal resolution: Discrete time steps with probabilistic cell behaviors

- Key interactions: Androgen-dependent proliferation, macrophage-mediated killing, spatial competition

Experimental Protocol: Model Parameterization and Validation

Protocol 1: Parameter Optimization via Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

Objective: Calibrate model parameters to match in vitro co-culture growth data

Input Preparation:

- Collect in vitro growth curves from six technical replicates across three biological replicates

- Include data from both androgen-proficient (R1881) and androgen-deprived (vehicle control) conditions

- Measure growth dynamics for mono-cultures and co-cultures of all cell types

Optimization Setup:

- Define parameter search space for each cellular behavior:

- Tumor cell proliferation probability (TUpprol)

- M1 macrophage killing probability (M1pkill)

- M2 macrophage killing probability (M2pkill)

- Fibroblast proliferation parameters

- Initialize PSO with 50 particles and maximum iteration count of 200

- Set objective function as mean squared error between simulated and experimental growth curves

- Define parameter search space for each cellular behavior:

Validation Protocol:

- Compare optimized simulation output against hold-out experimental data

- Validate spatial patterns against histological samples from human prostate tumor tissue

- Perform sensitivity analysis on key parameters to assess robustness

Protocol 2: Simulation of Therapeutic Interventions

Objective: Investigate ADT effects on tumor-stromal-immune crosstalk

Baseline Configuration:

- Initialize grid with random distribution of all cell types

- Set initial proportions based on histological quantification:

- Tumor cells: 40-60%

- Fibroblasts: 20-30%

- Macrophages (M1/M2): 10-20%

Intervention Protocol:

- Run simulation for 1000 time steps under androgen-proficient conditions

- Switch to androgen-deprived conditions to simulate ADT

- Monitor emerging spatial patterns and cell population dynamics

- Track formation of CRPC-resistant clusters

Output Analysis:

- Quantify cluster size distribution of resistant tumor cells

- Measure spatial correlation between fibroblasts and tumor survival niches

- Calculate killing efficiency of M1 macrophages pre- and post-ADT

Table 2: Key Parameters from Optimized Prostate Cancer ABM

| Parameter | Androgen-Proficient Conditions | Androgen-Deprived Conditions | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| TUpprol | 0.1144 | 0.0389 | Tumor cell proliferation probability |

| M1pkill | 0.1116 | 0.0050 | M1 macrophage killing capacity |

| M2pkill | 0.0005 | 0.0003 | M2 macrophage killing capacity |

| Emergent CRPC Foci | None | Multifocal clusters | Spatial pattern of therapy resistance |

Key Findings and Biological Validation

The PCABM simulations revealed several critical insights validated against experimental and clinical observations:

CRPC Development is Spatially Structured: Resistant cells emerged in distinct clusters rather than dispersed individually, mirroring the multifocal nature of clinical prostate cancer [16].

Fibroblasts Create Protective Niches: Simulations demonstrated that fibroblasts compete for physical space while simultaneously creating protective environments that shield tumor cells from macrophage-mediated killing [16].

ADT Has Immunomodulatory Effects: The optimized model predicted a 22-fold reduction in M1 macrophage killing capacity under androgen-deprived conditions, suggesting ADT indirectly promotes tumor survival by suppressing anti-tumor immunity [16].

Essential Toolkits for Spatial ABM Implementation

Computational Frameworks and Software

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Agent-Based Modeling

| Tool/Solution | Type | Primary Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PhysiCell | ABM Software Platform | Simulates 3D multicellular systems | High flexibility; requires programming expertise |

| Hybrid Automata Library | ABM Framework | Multi-scale modeling with cellular automata | Intermediate complexity; good for hybrid models |

| NetLogo | ABM Environment | Rapid prototyping of agent-based systems | Beginner-friendly; lower computational performance |

| Particle Swarm Optimization | Calibration Algorithm | Parameter estimation from experimental data | Requires substantial computational resources |

| nanoHUB Integration | Visualization Interface | Web-based 3D simulation visualization | Enables non-expert interaction with calibrated models |

Experimental Data for Model Parameterization

Successful ABM implementation requires integration with experimental data at multiple stages:

Spatial Validation Data Sources:

- Multiplexed immunofluorescence of patient tissue sections

- Spatial transcriptomics (10X Genomics Visium, NanoString GeoMX)

- Single-cell RNA sequencing with spatial reconstruction

- Live-cell imaging of co-culture systems

Figure 2: Integrative science workflow for agent-based model development, showing the iterative cycle between experimental data generation and computational model refinement.

Advanced Applications: Integrating ABMs with Spatial Technologies

Coupling ABMs with Spatial Biology Platforms

The increasing availability of high-resolution spatial data from platforms like 10X Genomics Visium HD, NanoString GeoMX, and Lunaphore COMET enables unprecedented calibration of ABM parameters [17] [18]. These technologies provide quantitative data on:

- Cellular neighborhood compositions in intact tissues

- Gradient formation of signaling molecules and metabolites

- Immune cell infiltration patterns with simultaneous phenotype characterization

- Subcellular localization of key therapeutic targets

Protocol: Spatial Data Integration for ABM Refinement

Protocol 3: Incorporating Spatial Heterogeneity Metrics from Transcriptomic Data

Objective: Calibrate ABM initial conditions and interaction rules using spatial transcriptomics

Data Processing:

- Calculate intra-tumoral heterogeneity scores from multi-region sequencing data

- Identify genes with high inter- and intra-tumor expression variation

- Map spatial expression gradients to corresponding cellular interactions in ABM

Model Initialization:

- Set initial agent distributions based on cellular composition from spatial data

- Parameterize interaction probabilities using cell-cell proximity analyses

- Define diffusible factor gradients based on measured cytokine distributions

Validation Against Spatial Patterns:

- Compare simulated spatial heterogeneity with observed transcriptomic heterogeneity

- Validate predicted cellular neighborhood formations against multiplexed imaging

- Test model's ability to recapitulate geospatial transitions from tumor border to core

The progression from simple Eden growth models to sophisticated, spatially-explicit ABMs represents a critical evolution in computational oncology. By capturing the emergent behaviors that arise from cellular interactions within complex tissue environments, ABMs provide unique insights into therapy resistance mechanisms and metastatic processes that remain invisible to population-averaged modeling approaches.

The integration of ABMs with high-resolution spatial biology technologies and the development of rigorous calibration protocols—as demonstrated in the prostate cancer ABM case study—will be essential for advancing toward clinically predictive models. These integrative approaches promise to accelerate therapeutic discovery by enabling in silico screening of combination therapies, identification of novel biomarkers based on spatial organization, and ultimately, the development of truly personalized treatment strategies informed by a patient's specific tumor architecture.

The Critical Impact of Tumor Microenvironment (TME) Heterogeneity

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a complex, dynamic ecosystem consisting of neoplastic epithelial cells, immune cells, stromal cells, endothelial cells, extracellular matrix (ECM), cytokines, and metabolites [19]. These components engage in continuous crosstalk, influencing tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and therapeutic response. TME heterogeneity refers to the spatial and temporal variations in the composition, functional states, and spatial organization of these cellular and non-cellular components within and across tumors [20] [21]. This heterogeneity is a critical determinant of immunotherapy resistance, as it creates specialized niches that can suppress anti-tumor immune responses [19].

The immunosuppressive properties of the TME represent one of the primary mechanisms driving resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) [19]. Understanding this heterogeneity is therefore paramount for developing effective therapeutic strategies. Agent-based models (ABMs) have emerged as powerful computational tools to capture this spatial heterogeneity, modeling individual cell behaviors and interactions to reveal emergent tumor dynamics that simpler, non-spatial models cannot predict [8].

Key Components of the Heterogeneous TME and Their Roles in Immunotherapy Resistance

The following table summarizes the major cellular players in the TME, their subpopulations, and their roles in promoting an immunosuppressive landscape.

Table 1: Key Immunosuppressive Components of the Heterogeneous TME

| Component | Key Subtypes/Functions | Impact on Immunotherapy Resistance |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) [19] | M1 (pro-inflammatory, anti-tumor) and M2 (anti-inflammatory, pro-tumor) polarization states. | M2-polarized TAMs secrete immunosuppressive cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β), express PD-L1, and recruit Tregs, directly inhibiting cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) function. |

| Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) [19] [21] | Inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs), myofibroblastic CAFs (myoCAFs). Multiple subtypes identified via scRNA-seq (e.g., F3 in low-grade breast tumors) [21]. | Secrete cytokines/chemokines that recruit immunosuppressive cells. Remodel the ECM, creating a physical barrier that limits immune cell infiltration and increases matrix stiffness. |

| Immunosuppressive Cytokines [19] | Transforming Growth Factor-Beta (TGF-β), Interleukin-10 (IL-10). | Directly inhibits the activation, proliferation, and cytotoxic activity of CD8+ T cells and Natural Killer (NK) cells. Promotes the differentiation and function of Regulatory T cells (Tregs). |

| Regulatory T Cells (Tregs) [19] | CD4+ T cells expressing high levels of the transcription factor Foxp3. | Suppress effector T cell function via cytokine secretion (IL-10, TGF-β) and direct cell contact-mediated inhibition. |

| Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) [19] | Polymorphonuclear (PMN-MDSC) and monocytic (M-MDSC) subsets. | Expand in tumor-bearing hosts and potently suppress T cell function through arginase-1 production, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and nitric oxide (NO). |

| Metabolic Reprogramming [19] | High lactate production via aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect). Competition for key nutrients like glucose and glutamine. | Creates an acidic, nutrient-poor TME that directly impairs CTL metabolism and function, leading to T cell exhaustion and anergy. |

Quantitative Analysis of TME Heterogeneity

Advanced single-cell and spatial transcriptomic technologies have enabled the quantitative deconstruction of TME heterogeneity, revealing its prognostic and predictive significance.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics of TME Heterogeneity from Profiling Studies

| Metric | Measurement Technique | Finding | Clinical/Functional Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular Diversity [20] | Pan-cancer single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) of 230 treatment-naive samples across 9 cancer types. | Identification of 70 shared pan-cancer cell subtypes. | Subtypes co-occurred in two TME "hubs": one resembling Tertiary Lymphoid Structures (TLS), and another PD1+/PD-L1+ immune-regulatory hub. Hub abundance linked to early and long-term ICI response. |

| Spatial Organization [21] | Integrated scRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics of Breast Cancer (BRCA) samples. | Identification of 15 major cell clusters and numerous subtypes (e.g., 10 fibroblast, 10 myeloid, 12 T/B cell subpopulations). | Low-grade tumors enriched for specific subtypes (e.g., CXCR4+ fibroblasts, IGKC+ myeloid cells) despite favorable clinical features, were linked to reduced immunotherapy responsiveness. |

| T Cell States [21] | Reclustering of T lymphocytes from BRCA scRNA-seq data. | Identification of 19 immune subpopulations with distinct functional profiles (e.g., C2: GNLY+ NKT cells, C5: IL7R+ CD8+ T cells). | C5 (IL7R+ CD8+) cell infiltration inversely correlated with cytotoxic and exhaustion scores. Lower C5 infiltration was associated with worse prognosis in TCGA-BRCA cohort. |

| Intratumoral Genetic Heterogeneity [22] | CT-texture-guided multi-region biopsy with exome sequencing in lung cancer. | In 7 of 12 patients, >10% of mutations were exclusive to a single biopsy. 67% of cases showed >2 subclonal processes. | Radiomic "entropy" features correlated with genetic heterogeneity and identified a subcluster with a higher prevalence of STK11 mutations. |

Experimental Protocols for Profiling TME Heterogeneity

Protocol 4.1: Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics for TME Deconstruction

This protocol outlines an integrated approach to characterize cellular heterogeneity and spatial architecture of the TME [20] [21].

I. Sample Preparation and Single-Cell Sequencing

- Tissue Collection: Obtain fresh tumor samples (e.g., treatment-naive breast cancer specimens) and process into single-cell suspensions using mechanical dissociation and enzymatic digestion (e.g., collagenase IV, DNase I).

- Cell Viability and Sorting: Assess viability (>80% required) using trypan blue or propidium iodide. Optionally, sort live cells using FACS.

- scRNA-seq Library Preparation: Use a platform like the 10x Genomics Chromium system to capture thousands of individual cells and barcode mRNA. Generate sequencing libraries per manufacturer's instructions.

- Sequencing: Sequence libraries on an Illumina platform to a recommended depth of >50,000 reads per cell.

II. Computational Data Analysis

- Preprocessing: Use Cell Ranger (10x Genomics) to demultiplex data, align reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38), and generate gene-cell count matrices.

- Quality Control and Filtering: Filter out cells with high mitochondrial gene percentage (>20%) or low unique gene counts, indicating poor-quality cells or empty droplets.

- Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Use Seurat or Scanpy for downstream analysis. Normalize data, identify highly variable genes, and perform linear dimensionality reduction (PCA). Cluster cells using a graph-based method (e.g., Louvain algorithm) in PCA space.

- Cell Type Annotation: Project cells into 2D space using UMAP. Annotate cell clusters based on canonical marker genes:

- Epithelial cells: EPCAM, KRT18, KRT19

- T cells: CD3D, CD3E, CD3G

- B cells: CD79A, MS4A1

- Myeloid cells: LYZ, CD68

- Fibroblasts: DCN, THY1, COL1A1

- Endothelial cells: PECAM1, CLDN5

- Subcluster Analysis: Isolate major cell lineages (e.g., fibroblasts, T cells) and repeat steps 3-4 to identify transcriptionally distinct subtypes.

III. Spatial Transcriptomics Integration

- Spatial Library Preparation: Process adjacent tissue sections on a spatial transcriptomics platform (e.g., 10x Genomics Visium).

- Cell-Type Deconvolution: Employ computational tools like CARD or cell2location to map the cell subtypes identified in scRNA-seq onto the spatial transcriptomics spots, inferring their spatial distribution.

- CNV Inference: Use tools like inferCNV on the spatial data to distinguish neoplastic epithelial cells from non-malignant cells based on genomic copy number variation patterns.

- Spatial Analysis: Identify co-localization patterns of cell subtypes (e.g., immune-reactive hubs) and correlate their spatial proximity with clinical outcomes or ICI response data [20].

Protocol 4.2: Agent-Based Modeling of Spatial TME Heterogeneity

This protocol details the creation of an ABM to simulate tumor-immune interactions in a spatially explicit context, highlighting its advantages over non-spatial models [8].

I. Model Conceptualization and Design

- Define Agent Types and Rules: Specify the agents to be included (e.g., Tumor Cells with high/low antigenicity, Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes (CTLs), TAMs). Define their behavioral rules:

- Tumor Cells: Proliferate, can be killed by CTLs via Fas/FasL or perforin/granzyme pathways. Antigenicity influences kill mechanism.

- CTLs: Move randomly or via chemotaxis, recognize tumor cells based on antigenicity, kill upon contact, and can become exhausted.

- TAMs: Can be polarized to M1 or M2 states, influencing local immune suppression.

- Define the Spatial Environment: Create a 2D or 3D lattice representing the tissue space. Incorporate environmental features like blood vessels (source of immune cells) and regions of variable ECM density (influencing agent motility).

- Parameterization: Initialize the model with parameters for agent counts, movement speeds, proliferation rates, and killing efficiencies derived from experimental data or literature.

II. Model Implementation and Simulation

- Programming: Implement the model using a specialized ABM platform (e.g., NetLogo, CompuCell3D) or a general-purpose language (e.g., Python).

- Simulation Execution: Run the simulation for a defined number of time steps. At each step, agents interact with each other and their environment based on the predefined rules.

III. Model Validation and Analysis

- Output Comparison: Compare model outputs, such as tumor size, immune cell infiltration patterns, and phenotypic shifts within the tumor population, with in vivo observations or in vitro data.

- Comparison with ODE Model: Contrast the results with a similar, non-spatial Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) model. The ABM is expected to reveal more complex and realistic dynamics, such as the formation of immune-suppressive niches and heterogeneous tumor regions that the ODE model cannot capture [8].

- Therapeutic Testing: Use the validated ABM to simulate therapeutic interventions, such as anti-PD-1 ICI administration, and predict outcomes based on different initial TME configurations.

Visualization of TME Heterogeneity and Agent-Based Modeling

Diagram 1: TME Heterogeneity & Immunosuppression

Diagram 2: Agent-Based Model of The TME

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for TME Heterogeneity Studies

| Category / Reagent | Specific Example(s) | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq Platforms | 10x Genomics Chromium | High-throughput single-cell capture, barcoding, and library preparation for transcriptomic profiling of heterogeneous TME cell populations. |

| Spatial Biology Platforms | 10x Genomics Visium, NanoString GeoMx | Enables transcriptomic or proteomic analysis within the original tissue context, preserving spatial relationships between cell subtypes. |

| Cell Type Markers (Antibodies) | Anti-EPCAM (epithelial), Anti-CD3 (T cells), Anti-CD68 (myeloid), Anti-FAP (CAFs), Anti-FoxP3 (Tregs) | Identification, isolation (via FACS), and spatial validation of specific TME cell types and subtypes via flow cytometry or immunohistochemistry. |

| Cytokine Analysis | TGF-β, IL-10 ELISA or Luminex kits | Quantification of immunosuppressive cytokine levels in tumor-conditioned media or patient serum to assess TME immunosuppressive status. |

| Computational Tools | Seurat, Scanpy, CARD, inferCNV | Bioinformatic pipelines for analyzing scRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics data, including cell clustering, annotation, and copy number variation inference. |

| Modeling Software | NetLogo, CompuCell3D, Python (Mesa) | Platforms for developing, running, and analyzing Agent-Based Models to simulate spatial tumor-immune dynamics and therapy responses. |

Building and Applying Spatial Tumor Models: From Theory to Therapeutic Insights

A Seven-Step Guide to Developing SABMs from First Principles

Spatial Agent-Based Models (SABMs) have become indispensable tools in quantitative oncology for simulating complex tumor dynamics. These computational models simulate the behavior and interaction of individual cells (agents) within spatially explicit environments, making them particularly suited for investigating cancer stem cell driven tumor growth and tumor-macrophage interactions [23] [24]. The power of SABMs lies in their ability to capture how localized cell-cell interactions and microenvironmental heterogeneity give rise to emergent population-level dynamics that can be validated with both in vitro and in vivo experiments [23]. As spatial genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic technologies advance, these spatial computational models are predicted to become ever more necessary for making sense of complex clinical data sets, predicting clinical outcomes, and optimizing cancer treatment strategies [1].

This guide provides a structured framework for developing SABMs from first principles, emphasizing how to tailor model structure to biological systems. We stress the importance of matching model complexity to the phenomena of interest rather than attempting to replicate the entire biological system [1]. By following these seven steps, researchers can create robust models that provide insights into spatial aspects of tumour evolution—especially crucial in carcinomas, which constitute the majority of human cancers [1].

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

First Principles Thinking in Model Development: First principles thinking involves breaking down complex problems into their most fundamental components and rebuilding solutions from scratch. In software development, this approach has been championed by innovators like Elon Musk, who used it to deconstruct problems such as battery costs by analyzing raw material expenses rather than accepting prevailing market prices [25]. Applied to SABM development, this means understanding and coding the basic rules of cell behavior rather than relying solely on pre-existing modeling frameworks.

Spatial Heterogeneity in Tumors: Tumors are highly heterogeneous structures containing diverse populations of tumor cells, blood vessels, stromal cells, and immune cells [24]. Spatial heterogeneity refers to the uneven distribution of traits or events between regions, which can be quantified using spatial statistics [26]. This heterogeneity significantly influences disease progression and therapeutic outcomes, necessitating modeling approaches that can capture both spatial and phenotypic variation.

Agent-Based Modeling Fundamentals: SABMs are computational models of systems made up of autonomous, interacting "agents" [1]. In oncology applications, these agents typically represent individual cells or cell subpopulations whose behaviors are governed by rules informed by biological data. The spatial structure parameters determine the evolutionary balance between selection and drift, the nature of gene flow between subpopulations, and the strength of ecological interactions [1].

Step-by-Step Protocol for SABM Development

Step 1: Establish the Modeling Framework and Lattice Structure

The foundation of any SABM begins with defining its spatial architecture. Implement all classes and functions in a concurrent version system to enable shared programming and efficient debugging throughout the development process [23].

- Lattice Definition: Create a finite 2D or 3D lattice where each site can be occupied. Determine the lattice size to accommodate the anticipated final cell number, accounting for possible boundary effects during population growth. Set the size of a single lattice site to correspond to the size of a cell being modeled [23].

- Neighborhood Configuration: Define how cells interact by selecting either a von Neumann neighborhood (four orthogonal neighbors: north, south, east, west) or a Moore neighborhood (eight adjacent lattice points including diagonals) as shown in [23].

- Boundary Conditions: Specify behavior at lattice edges using either periodic (wrapping) boundaries or no-flux reflective boundaries. For dynamically expanding arrays, no boundary conditions are necessary [23].

Step 2: Define Agent Attributes and States

Each cell in the model functions as an individual entity with specific attributes that dictate its behavior. The core attributes should include [23]:

- Cell Type Status: Define whether a cell is a stem (

isStem = true) or non-stem (isStem = false) cancer cell, as cancer stem cells possess distinct properties including superior DNA damage repair mechanisms [23]. - Division Probability: For cancer stem cells, define the probability of symmetric division (

ps) producing two identical cancer stem cells, versus asymmetric division (pa = 1 - ps) producing one stem cell and one non-stem cell [23]. - Proliferation Capacity: Implement a molecular clock such as telomere length (

p) to quantify the Hayflick limit, particularly for non-stem cancer cells that do not upregulate telomerase [23]. - Death Probability: Define probability of spontaneous death (

α), typically higher for non-stem cancer cells due to genomic instability [23].

Step 3: Implement Core Agent Behavioral Functions

Agents require programmed functions that determine their responses to environmental conditions and internal states. These core procedures include [23]:

- Time Advancement Procedure: Create an

advance timefunction with input arguments for time increment (Δt) and list of available neighboring sites. This function should decrease the time to next division, update cell cycle phase if necessary, and trigger division when conditions are met [23]. - Division Procedure: Implement a

dividefunction that checks for available space, handles cell death based on probability α, and determines division type (symmetric vs. asymmetric) for stem cells. For non-stem cells, decrease proliferation capacity and simulate death if exhausted [23]. - Migration Procedures: Develop both

random migrationusing a discretized diffusion equation approach anddirected migrationfunctions that respond to chemical gradients (e.g., chemoattractants or chemorepellants) for more biologically realistic cell movement [23].

Step 4: Select Programming Environment and Tools

Choose appropriate computational resources based on project requirements and team expertise. Consider the trade-offs between different programming languages and platforms [23]:

- Programming Languages: Options include C++ (best performance, high complexity), Java, Julia, Python, or Matlab (easier coding, lower performance) [23].

- Agent-Based Modeling Platforms: Utilize predeveloped software packages such as NetLogo, CompuCell3D, Chaste, or Swarm to accelerate model development [23].

- Visualization Tools: Implement graphical output using existing graphical programming implementations or develop custom visualization tools specific to your modeling needs [23].

Step 5: Configure Simulation Parameters and Scheduling

Establish the temporal framework that governs model execution to ensure biological fidelity:

- Time Step Determination: Set the simulation time step (Δt) such that it is smaller than the fastest biological process being considered. In models incorporating both cell proliferation (~1/day) and migration (~1 cell width/hour), set Δt ≤ 1 hour [23].

- Event Scheduling: Develop a simulation flowchart to conceptualize and visualize the simulation procedure. At each discrete time step, process mutually exclusive events in order of their rate constants, with lowest rate processes typically considered first [23].

- Update Rules: Implement asynchronous updating where only one or a small number of sites are modified per update. This approach is more biologically realistic for processes like cell division and necessary to prevent conflicts when multiple cells attempt to divide into limited spaces [1].

Step 6: Implement from Simple to Complex Models

Begin with basic models and progressively add complexity to ensure understanding and robustness:

- Start with Eden Growth Models: Implement simple stochastic cellular automata with two states (unoccupied and occupied) where new cells are added to cluster surfaces. Choose among three update rules: (A) Available site-focussed, (B) Bond-focussed, or (C) Cell-focussed, which generate clusters with different surface properties from roughest to smoothest [1].

- Introduce Spatial Branching Processes: Extend basic models by allowing dividing cells without space to create space by budging nearby cells, simulating physical constraints on cell division. Implement budging along approximately straight lines between dividing cells and nearest empty sites to avoid artificial geometric shapes [1].

- Incorporate Phenotypic Heterogeneity: Add continuous phenotypic variables, such as macrophage phenotype ranging from anti-tumour to pro-tumour, to capture more sophisticated biological interactions. This enables modeling of dynamic phenotype changes in response to microenvironmental cues [24].

Step 7: Calibrate, Validate, and Analyze Model Output

The final step ensures model outputs yield biologically meaningful insights:

- Parameterization: Calibrate behavioral rules using data from in vitro assays such as clonogenic assays or live microscopy imaging. Derive specific cell cycle times (t_c) from proliferation rate calculations [23].

- Spatial Analysis: Apply spatial statistics like the weighted Pair Correlation Function (wPCF) to analyze synthetic images generated by the ABM. The wPCF describes spatial relationships between points marked with combinations of discrete and continuous labels, providing "human readable" statistical summaries of spatial relationships [24].

- Validation: Compare emerging population-level dynamics with both in vitro and in vivo experimental data to validate model predictions [23].

Table 1: Essential Cell Attributes for Cancer SABMs

| Attribute | Symbol | Description | Typical Values/Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to next division | t_c | Time until cell attempts division | Average ~24 hours [23] |

| Cell type status | isStem | Boolean for stem/non-stem classification | true or false [23] |

| Symmetric division probability | p_s | Probability stem cell division produces two stem cells | 0 < p_s ≤ 1 [23] |

| Telomere length/Proliferation capacity | p | Molecular clock limiting divisions | Variable [23] |

| Spontaneous death probability | α | Probability of cell death during division attempt | Higher for non-stem cells [23] |

Table 2: Comparison of SABM Implementation Options

| Component | Option A | Option B | Option C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood Type | Von Neumann (4 orthogonal neighbors) [23] | Moore (8 adjacent neighbors) [23] | - |

| Boundary Conditions | Periodic (wrapping) [23] | No-flux reflective [23] | Dynamically expanding [23] |

| Eden Model Update Rule | Available site-focussed (roughest surface) [1] | Bond-focussed (intermediate surface) [1] | Cell-focussed (smoothest surface) [1] |

| Programming Language | C++ (high performance) [23] | Python/Matlab (easier coding) [23] | Java/Julia (balanced) [23] |

Visualization of SABM Workflow

SABM Development Workflow: This diagram illustrates the sequential seven-step process for developing Spatial Agent-Based Models, highlighting two critical cyclic components for lattice configuration and agent definition that require iterative refinement.

Cell Division Logic: This flowchart details the conditional decision process during cell division in SABMs, encompassing space availability checks, spontaneous death probability, stem cell division type determination, and proliferation capacity management for non-stem cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SABM Development

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Programming Environments | C++, Java, Julia, Python, Matlab [23] | Core languages for implementing model logic with different performance/complexity trade-offs |

| ABM Platforms | NetLogo, CompuCell3D, Chaste, Swarm [23] | Predeveloped software packages that accelerate model development and provide built-in functions |

| Spatial Analysis Tools | Weighted Pair Correlation Function (wPCF) [24] | Spatial statistic that describes relationships between points with continuous and discrete labels |

| Visualization Systems | Custom graphical tools, platform-specific visualizers [23] | Generate graphical outputs of simulation results for analysis and presentation |

| Data Sources for Calibration | Clonogenic assays, live microscopy imaging [23] | Experimental data used to parameterize cell cycle times, division rates, and migration probabilities |

| Version Control Systems | Git, SVN, Concurrent Version Systems [23] | Manage code development, enable collaborative programming, and maintain reproducibility |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The development of SABMs from first principles enables researchers to address increasingly complex questions in oncology. Advanced applications include:

Tumor-Macrophage Interaction Modeling: Implement models that simulate interactions between macrophages and tumour cells influenced by both spatial positions and continuous phenotypic variables. Use the weighted PCF to analyze synthetic images generated by the ABM, creating interpretable statistical summaries of where macrophages with different phenotypes are located relative to both blood vessels and tumour cells [24].

Immunoediting Classification: Define distinct 'PCF signatures' that characterize the 'three Es of cancer immunoediting' - Equilibrium, Escape, and Elimination. Combine wPCF measurements with cross-PCF describing interactions between vessels and tumour cells, then apply dimension reduction techniques to identify key features for classification [24].

Integration with Multiplex Imaging: Apply methods like the wPCF to multiplex imaging data which provides exquisitely detailed information about spatial distribution and intensity of up to 40 biomarkers within tissue regions. This approach exploits continuous variation in biomarker intensities rather than simplifying to discrete categories, generating more detailed characterization of spatial and phenotypic heterogeneity in tissue samples [24].

As these methodologies advance, SABMs developed from first principles will continue to bridge the gap between experimental data and theoretical understanding, ultimately contributing to improved cancer treatment strategies and patient outcomes.

Spatial agent-based models (ABMs) are computational frameworks used to simulate systems composed of autonomous, interacting agents. In oncology, these agents are typically individual tumor, immune, or stromal cells whose behaviors are governed by rules that incorporate both intrinsic properties and local microenvironmental cues [1]. The core value of spatial ABMs lies in their ability to reveal how localized interactions—between cells and with their spatially varying environment—shape evolutionary processes such as selection, genetic drift, and gene flow within tumors [1]. The fundamental choice between a grid-based (on-lattice) or off-lattice architecture is pivotal, as it directly determines how spatial structure, a critical regulator of tumor evolution, is represented. This structural representation must be derived from empirical data wherever possible, as inaccuracies can lead to unreliable model predictions and inferences [1].

Core Architectural Frameworks

Grid-Based (On-Lattice) Models

Grid-based models constrain agents to the sites of a predefined lattice, such as a regular square or hexagonal grid in two dimensions, or a cubic grid in three dimensions.

Fundamental Principles: Each grid site is associated with one of a finite set of states (e.g., occupied by a specific cell type, or empty). The model evolves by updating these states according to rules based on the state of a site and the states of the sites in its immediate neighborhood, such as the Von Neumann (cardinal directions) or Moore (cardinal and diagonal directions) neighborhoods [1]. While some cellular automata use deterministic rules, probabilistic rules are more appropriate for modeling stochastic biological processes like tumor evolution, creating a system of locally interacting Markov chains where event probabilities depend only on the current model state [1].

The Eden Growth Model and Its Variants: The Eden growth model is a foundational stochastic cellular automaton for simulating cluster growth. It uses only two states: unoccupied (S0) and occupied (S1). With each iteration, an unoccupied site adjacent to an occupied site becomes occupied. The specific update rule influences the resulting morphology [1]:

- Available Site-Focussed (Option A): An empty site adjacent to any occupied site is chosen at random and occupied. This produces the roughest cluster surface.

- Bond-Focussed (Option B): An occupied site is chosen with probability proportional to its number of empty neighbors; one of those empty neighbors is then occupied.

- Cell-Focussed (Option C): An occupied site with at least one empty neighbor is chosen at random; one of its empty neighbors is then occupied. This produces the smoothest cluster surface.

Variants of the Eden model that incorporate stochastic cell death have been applied to study pediatric glioma, colon cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma, as cell death opens space for division and increases clonal mixing [1].

Advanced Grid-Based Frameworks: More complex models like spatial branching processes introduce mechanisms like "budging," where a dividing cell without adjacent space can push other cells along an approximately straight line toward the nearest empty site to create room for its daughter cell. This simulates physical constraints on division more realistically than budging restricted only to cardinal directions, which can create artificially angular tumor shapes [1].

Off-Lattice Models

Off-lattice models position agents freely within a continuous space, removing the geometric constraints of a grid.

Fundamental Principles: In these models, each cell (agent) is represented as a discrete object with a defined position, often incorporating physical properties such as volume, adhesion, and elastic deformation. A classic example is the IBCell model, which represents individual cells as deformable objects and couples them with continuum equations solved on a separate grid to describe fluid dynamics (e.g., of the cytoplasm or external medium) or diffusible factors [27]. This approach allows for a more biophysically realistic representation of cell shapes, mechanical interactions, and tissue morphology, enabling the simulation of normal epithelial structures and abnormal patterns like the cribriform morphology seen in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) [27].

Hybrid Discrete-Continuous Frameworks: The term "hybrid model" classically refers to the coupling of discrete cell descriptions with continuous descriptions of microenvironmental factors. These continuous factors, such as nutrient concentrations (oxygen), growth factors (VEGF), or therapeutic agents, are typically modeled using partial differential equations (PDEs) solved over the spatial domain [27]. The discrete and continuous components are bidirectionally linked: the continuous fields influence cell behavior (e.g., proliferation in high oxygen, death in low oxygen), while cells alter the continuous fields (e.g., consuming nutrients, secreting signaling molecules) [27] [10].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Grid-Based and Off-Lattice Architectures

| Feature | Grid-Based (On-Lattice) Models | Off-Lattice Models |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Representation | Discrete, predefined lattice sites [1] | Continuous, free coordinates [27] |

| Computational Cost | Generally lower; scales with number of sites [1] | Generally higher; scales with number and complexity of agents [27] |

| Handling of Cell Mechanics | Implicit, via occupancy rules [1] | Explicit, can include volume, adhesion, deformation [27] |

| Implementation of Crowding | Simple; a site can be occupied by only one agent [1] | Emergent; result of physical forces and agent volumes [27] |

| Morphological Output | Can be pixilated or angular; sensitive to grid geometry [1] | Smooth, biologically realistic tissue shapes and patterns [27] |

| Typical Applications | Large-scale evolutionary studies, screening hypotheses [1] | Studying biophysical mechanisms, tissue-scale morphology [27] |

Quantitative Comparison and Selection Guidelines

The decision between grid-based and off-lattice frameworks is not about finding a universally superior option, but rather selecting the most appropriate tool for a specific research question. The following table provides a high-level guide for this decision-making process.

Table 2: Framework Selection Guide Based on Research Objectives

| Research Objective | Recommended Framework | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Large-scale clonal evolution & population genetics | Grid-Based | Computational efficiency allows for simulating large cell numbers over many generations to track mutation spread and drift [1]. |

| Studying biophysical mechanisms & cell mechanics | Off-Lattice | Explicit representation of physical forces, deformations, and adhesive interactions is essential [27]. |

| Predicting emergent tissue morphology | Off-Lattice | Capable of generating realistic, smooth tissue architectures (e.g., ductal structures) that are constrained by grid geometry in on-lattice models [27]. |