Validation of Biomarkers to Predict Immunotherapy Response: A Comprehensive Guide from Discovery to Clinical Application

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of predictive biomarkers for cancer immunotherapy.

Validation of Biomarkers to Predict Immunotherapy Response: A Comprehensive Guide from Discovery to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of predictive biomarkers for cancer immunotherapy. It covers the foundational landscape of established and emerging biomarkers, details the stepwise methodological process from analytical to clinical validation, addresses key challenges and optimization strategies, and explores regulatory frameworks and comparative analysis of validation trial designs. By synthesizing current standards and future directions, this guide aims to accelerate the development of robust biomarkers to improve patient selection and outcomes in immuno-oncology.

The Evolving Landscape of Immunotherapy Biomarkers: From Discovery to Clinical Imperative

The Critical Need for Predictive Biomarkers in Immuno-Oncology

Cancer immunotherapy, particularly the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), has fundamentally transformed oncology by enabling durable, long-lasting responses in multiple malignancies including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), melanoma, and triple-negative breast cancer [1]. These treatments work by blocking inhibitory pathways such as programmed cell death protein-1/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), thereby restoring T-cell-mediated antitumor immunity [1]. Despite demonstrated successes across diverse tumor types, only a subset of patients derives clinical benefit from these interventions, while all patients face potential immune-related adverse events (irAEs) and significant financial costs [1] [2].

This variability in treatment response underscores the critical need for robust predictive biomarkers to guide therapy selection, optimize clinical outcomes, and reduce unnecessary toxicity [1]. The ideal biomarker should be specific, reproducible, clinically accessible, and mechanistically informative, though current candidates face challenges including tumor heterogeneity, assay variability, and dynamic biomarker expression across tumor sites and disease stages [1]. This review synthesizes current evidence on predictive biomarkers in immuno-oncology, comparing their performance characteristics, validation methodologies, and clinical applications to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Established Predictive Biomarkers: Clinical Validation and Performance

PD-L1 Expression

PD-L1, the ligand for PD-1, is frequently expressed on antigen-presenting cells and tumor cells, where its expression is often induced by interferon-gamma within the tumor microenvironment [1]. When PD-L1 binds PD-1, T-cell activation becomes inhibited, resulting in immune tolerance [1]. ICIs targeting this pathway include pembrolizumab and nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitors) and atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab (PD-L1 inhibitors) [1].

PD-L1 has emerged as a key predictive biomarker in NSCLC, with the KEYNOTE-024 trial demonstrating that patients with PD-L1 expression ≥50% experienced significantly improved outcomes with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy, showing a median overall survival (OS) of 30 months versus 14.2 months (HR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.47-0.86) [1]. These findings led to pembrolizumab's approval as first-line therapy in advanced NSCLC with high PD-L1 expression [1]. However, the CheckMate-026 trial using nivolumab failed to show similar OS or progression-free survival (PFS) advantages, highlighting the limitations of PD-L1 as a standalone biomarker due to assay variability, different detection antibodies, and tumor heterogeneity [1].

Microsatellite Instability (MSI) and Mismatch Repair Deficiency (dMMR)

MSI and dMMR reflect defects in DNA repair pathways, commonly observed in colorectal cancer, that result in high mutational burden and neoantigen formation [1]. The FDA granted tissue-agnostic approval to pembrolizumab in 2017 based on trials including KEYNOTE-016, KEYNOTE-164, and KEYNOTE-158, which demonstrated a 39.6% overall response rate (ORR) in MSI-high tumors, with durable responses in 78% of cases [1]. MSI-H/dMMR testing is now recommended in guidelines by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) as a robust predictor of response to immunotherapy, though its utility remains limited to a subset of patients across various cancer types [1].

Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB)

TMB measures the number of somatic mutations per megabase of DNA, reflecting neoantigen load and tumor immunogenicity [1]. Pembrolizumab received approval for tumors with TMB ≥10 mutations/Mb based on the KEYNOTE-158 trial, which demonstrated a 29% ORR in high-TMB tumors compared to 6% in low-TMB tumors [1]. Additional research by Gandara et al. reported that TMB ≥20 mutations/Mb was associated with improved survival across multiple cancer types (HR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.47-0.58) [1]. While TMB shows promise as a quantitative predictive marker, challenges remain in standardization across testing platforms and determination of optimal cut-off values across different cancer types.

Table 1: Comparison of Established Predictive Biomarkers in Immuno-Oncology

| Biomarker | Cancer Types | Predictive Value | Limitations | Regulatory Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD-L1 Expression | NSCLC, Melanoma, TNBC | ORR: 30-50% in PD-L1+ NSCLC; Median OS: 30 vs 14.2 mos in KEYNOTE-024 | Inter-assay variability, tumor heterogeneity, dynamic expression | FDA-approved companion diagnostic for multiple ICIs |

| MSI-H/dMMR | Colorectal, Endometrial, Pan-cancer | ORR: 39.6%; Durable responses in 78% | Limited to small patient subsets (2-4% in most cancers) | FDA-approved tissue-agnostic indication for pembrolizumab |

| Tumor Mutational Burden | Multiple solid tumors | ORR: 29% in TMB-high vs 6% in TMB-low; HR: 0.52 for survival in TMB ≥20 mut/Mb | Lack of standardized cut-offs, platform variability | FDA-approved for pembrolizumab in TMB ≥10 mut/Mb |

Emerging Biomarkers and Novel Approaches

Circulating Biomarkers and Liquid Biopsy

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) comprises tumor-derived DNA fragments in the bloodstream that offer a non-invasive biomarker approach for monitoring treatment response [1]. Research by Al-Showbaki et al. demonstrated that ≥50% ctDNA reduction within 6-16 weeks post-ICI therapy correlated with better PFS and OS across multiple tumor types [1]. Additionally, Tie et al. showed that a ctDNA-guided strategy could reduce adjuvant chemotherapy use in stage II colon cancer without compromising recurrence-free survival [1]. Liquid biopsies are poised to become standard tools in clinical practice by 2025, with advances in ctDNA analysis and exosome profiling expected to increase sensitivity and specificity for early disease detection and monitoring [3].

Other circulating biomarkers showing promise include relative eosinophil count (REC), with one study demonstrating that melanoma patients with REC ≥1.5% had a median OS of 27 months versus 5-7 months for those with lower counts [1]. Flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells has also revealed potential predictive value for absolute lymphocyte count and specific immune cell populations in response to CTLA-4 inhibition, though these approaches require further validation [2] [4].

Tumor Microenvironment Biomarkers

The tumor immune microenvironment plays a crucial role in mediating response to immunotherapy. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), consisting primarily of cytotoxic and helper T cells that infiltrate tumors, reflect host immune response and have demonstrated significant predictive value [1]. High TIL levels in triple-negative and HER2-positive breast cancers are associated with improved immunotherapy response and prognosis, leading to their incorporation into Scandinavian breast cancer guidelines and recognition by the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) for early-stage disease [1]. Despite the absence of universal scoring standards, TIL assessment offers a low-cost and reproducible biomarker approach [1].

Advanced multiplex immunohistochemistry and single-cell analysis technologies are enabling deeper characterization of the tumor microenvironment, identifying specific cell populations and spatial relationships that may predict treatment response more accurately than single-parameter biomarkers [3] [4]. Single-cell analysis technologies are expected to become more sophisticated and widely adopted by 2025, facilitating identification of rare cell populations that may drive disease progression or resistance to therapy [3].

Multi-Omics and Integrated Approaches

Given the complexity of tumor-immune interactions, multiparameter biomarker approaches are increasingly necessary for accurate prediction of clinical benefit [2]. Multi-omics approaches integrate genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to achieve a holistic understanding of disease mechanisms and identify comprehensive biomarker signatures [1] [3]. Research by Bourbonne et al. demonstrated approximately 15% improvement in predictive accuracy using multi-omics with machine learning models, while Li et al. identified specific gene clusters associated with durable response to PD-1 blockade [1].

In the Lung-MAP S1400I trial, investigators found that high CD8⁺GZB⁺ T-cell infiltration predicted better response to nivolumab, while IL-6 and CXCL13 levels were linked to resistance, illustrating the power of immune contexture profiling [1]. The trend toward multi-omics integration is expected to gain momentum through 2025, promoting systems biology approaches and fostering collaborative research efforts across bioinformatics, molecular biology, and clinical research [3].

Table 2: Emerging Biomarkers and Technologies in Immuno-Oncology

| Biomarker Category | Specific Markers | Potential Applications | Current Validation Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circulating Biomarkers | ctDNA, REC, MDSCs, Tregs | Response monitoring, early relapse detection, treatment selection | Preliminary clinical evidence; requires prospective validation |

| Tumor Microenvironment | TILs, CD8+GZB+ T cells, Spatial relationships | Predictive of response across multiple tumor types | Clinical validation ongoing; TILs incorporated into some guidelines |

| Multi-Omics Signatures | Genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic profiles | Patient stratification, combination therapy guidance | Research phase; machine learning models in development |

Biomarker Validation: Methodologies and Statistical Considerations

Validation Workflow and Regulatory Framework

The biomarker validation process requires careful attention to both analytical and clinical validation to establish clinical utility [2]. According to regulatory guidelines, biomarker assay validation can be separated into several continuous steps: assessment of basic assay performance (analytical validation); characterization of performance regarding intended use (clinical validation); and validation in independent cohorts to demonstrate clinical utility [2]. For a test to be considered a companion diagnostic, it must be essential for the safe and effective use of a corresponding therapeutic product and undergo rigorous review and approval by the FDA, requiring demonstration of analytical validity, clinical validity, and clinical utility [5].

The Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Immune Biomarkers Task Force has developed recommendations to guide analytical and clinical validation design for specific assays, emphasizing that validation should ultimately qualify assays for use in clinical decision-making [2]. Regulatory agencies are implementing more streamlined approval processes for biomarkers validated through large-scale studies and real-world evidence, with increasing recognition of real-world evidence in evaluating biomarker performance across diverse populations [3].

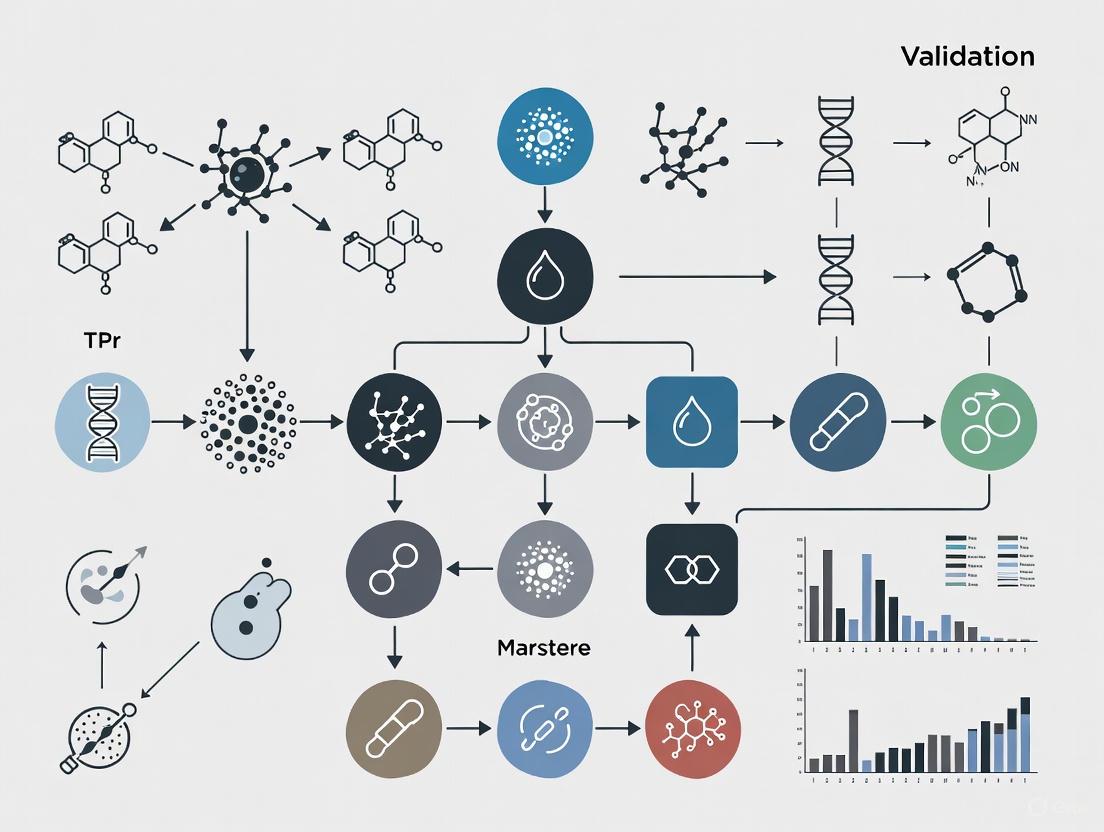

Biomarker Validation Pathway

Statistical Considerations and Methodological Challenges

Biomarker validation must discern associations occurring by chance from those reflecting true biological relationships, requiring careful attention to statistical methodologies [6]. Key considerations include controlling for multiplicity due to investigation of multiple biomarkers or endpoints, addressing within-subject correlation when multiple observations are collected from the same subject, and minimizing selection bias in retrospective studies [6] [7].

Multiplicity presents a particular challenge in biomarker studies because the probability of concluding that there is at least one statistically significant effect across a set of tests when no effect exists increases with each additional test [6]. Methods to control false discovery rate (FDR) are especially useful when using large-scale genomic or other high-dimensional data for biomarker discovery [7]. Additionally, studies with multiple endpoints require multiple testing corrections, prioritization of outcomes, or development of composite endpoints [6].

For predictive biomarker identification, proper statistical analysis requires testing for interaction between treatment and biomarker in a statistical model using data from randomized clinical trials [7]. An example is the IPASS study, which demonstrated a significant interaction between treatment and EGFR mutation status (P<.001) for gefitinib versus chemotherapy in lung cancer [7]. This contrasts with prognostic biomarkers, which can be identified through main effect tests of association between biomarker and outcome without requiring randomization [7].

Artificial Intelligence and Next-Generation Biomarker Discovery

AI-Driven Predictive Models

Artificial intelligence approaches are revolutionizing biomarker discovery by allowing exploitation of high-dimension oncological data in precision immuno-oncology [8]. A systematic review by Prelaj et al. identified 90 studies utilizing AI for predicting ICI efficacy across five data modalities: genomics, radiomics, digital pathology, real-world data, and multimodality data, with 80% published between 2021-2022 [8]. Standard machine learning methods were used in 72% of studies, deep learning methods in 22%, and both in 6%, with NSCLC (36%) and melanoma (16%) being the most frequently studied cancer types [8].

AI technologies enable development of sophisticated predictive models that can forecast disease progression and treatment responses based on complex biomarker profiles, enhancing clinical decision-making and optimizing patient management strategies [3] [9]. Machine learning algorithms also facilitate automated analysis of complex datasets, significantly reducing time required for biomarker discovery and validation [3]. By leveraging AI to analyze individual patient data alongside biomarker information, clinicians can develop tailored treatment plans that maximize efficacy while minimizing adverse effects [3].

Multi-Modal Data Integration

AI approaches have expanded the horizon for biomarker discovery by demonstrating the power of integrating multimodal data from existing datasets to discover new meta-biomarkers [8]. Complex algorithms and novel AI-based markers are emerging through integration of multimodal and multi-omics data, with AI-powered imaging tools improving assessment of tumor microenvironments and immune infiltrates [8] [9]. These approaches offer more precise predictions of therapy responses and aid in better clinical decision-making compared to single-modality biomarkers [9].

Emerging AI models trained on routine laboratory values, imaging data, and spatial "omics" now reportedly outperform PD-L1 in predicting response to immunotherapy, with potential for integration directly into hospital electronic medical records in the near future [10]. However, most studies to date have implemented AI as post hoc analyses rather than prospective designs incorporating AI-based methodologies from the outset, indicating the need for a priori planned prospective trial designs to cover all lifecycle steps of these software biomarkers [8].

AI-Driven Biomarker Discovery

Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies for Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Research

| Category | Specific Reagents/Technologies | Research Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunohistochemistry Assays | PD-L1 IHC 22C3, 28-8, SP142; Multiplex IHC panels | Protein expression analysis, spatial relationship mapping | Antibody validation, platform standardization, scoring protocols |

| Genomic Profiling | Next-generation sequencing panels, FoundationOne CDx, liquid biopsy assays | TMB assessment, MSI status, mutation profiling | Coverage depth, variant calling algorithms, input DNA requirements |

| Immune Monitoring | Multiparametric flow cytometry, ELISpot, single-cell RNA sequencing | Immune cell phenotyping, cytokine profiling, T-cell receptor repertoire | Panel design, sample processing, data normalization |

| Spatial Biology | Multiplex immunofluorescence, digital pathology, CODEX | Tumor microenvironment characterization, cellular interactions | Tissue preservation, image analysis algorithms, multiplexing capacity |

| AI/Computational Tools | Machine learning platforms, deep learning algorithms, data integration software | Predictive model development, biomarker signature identification | Data preprocessing, feature selection, model interpretability |

The field of predictive biomarkers for immuno-oncology is rapidly evolving beyond single-parameter biomarkers toward integrated approaches that capture the complexity of tumor-immune interactions [2]. While established biomarkers like PD-L1, MSI, and TMB provide foundation for treatment selection, emerging technologies including liquid biopsies, AI-driven models, and multi-omics signatures promise enhanced predictive accuracy [1] [8]. The successful clinical integration of these advanced biomarkers will require addressing ongoing challenges in standardization, validation, and equitable access [10].

Looking toward 2025, key trends expected to shape the biomarker landscape include enhanced integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning, rise of multi-omics approaches, advancements in liquid biopsy technologies, and adaptation of regulatory frameworks to accommodate novel biomarker types [3]. Additionally, focus on patient-centric approaches will become more pronounced, with biomarker analysis playing a key role in enhancing patient engagement and outcomes through improved education, incorporation of patient-reported outcomes, and engagement of diverse populations to ensure biomarker relevance across demographics [3]. As these technologies mature, the future of immuno-oncology will increasingly depend on validated predictive biomarkers to guide personalized treatment strategies and maximize therapeutic benefit while minimizing unnecessary toxicity and cost.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have fundamentally transformed cancer treatment, offering durable responses and prolonged survival for a subset of patients across numerous malignancies [11] [12]. However, clinical benefit remains heterogeneous, with only 20-30% of patients achieving durable responses, underscoring the critical need for robust predictive biomarkers to guide patient selection and optimize therapeutic outcomes [13]. The validation and implementation of biomarkers have become central to precision immuno-oncology, enabling clinicians to identify patients most likely to benefit from specific immunotherapy regimens.

The current clinical landscape is dominated by three established biomarkers: programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, microsatellite instability (MSI) or mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR), and tumor mutational burden (TMB) [12] [14]. These biomarkers provide insights into different aspects of the tumor-immune interaction, from immune checkpoint expression to underlying genomic instability and neoantigen load. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these established biomarkers, detailing their clinical validation, technical assessment, and predictive utility within the broader context of immunotherapy biomarker research.

Biomarker Comparison and Clinical Utility

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, clinical applications, and limitations of PD-L1, MSI/dMMR, and TMB in current clinical practice.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Established Immunotherapy Biomarkers

| Biomarker | Biological Rationale | Measurement Methods | FDA-Approved Contexts | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD-L1 | Measures adaptive immune resistance; PD-L1 binding to PD-1 on T cells inhibits anti-tumor immunity [14]. | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) with various assays (e.g., 22C3, 28-8, SP142, SP263) and scoring systems (TPS, CPS) [11] [12]. | Companion diagnostic for multiple cancers (NSCLC, HNSCC, gastric, TNBC) [11] [14]. | Significant spatial and temporal heterogeneity; assay and cutoff variability; dynamic expression [11] [12] [15]. |

| MSI/dMMR | Defective DNA repair → frameshift mutations → high neoantigen load → inflamed TME [16]. | IHC (loss of MMR proteins: MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) or PCR/NGS for MSI [16] [14]. | Tissue-agnostic indication for pembrolizumab and other ICIs [11] [16]. | Prevalence varies widely across cancer types; biological heterogeneity can modulate response [11] [15]. |

| TMB | High mutation count → increased neoantigen generation → enhanced immune recognition [14]. | Targeted NGS panels, whole exome sequencing (WES); defined as ≥10 mut/Mb for tissue-agnostic approval [11] [12]. | Tissue-agnostic companion diagnostic for pembrolizumab [11] [12]. | Lack of standardization across panels; predictive value inconsistent across tumor types [11] [12]. |

Biomarker Mechanisms and Predictive Value

Biological Pathways and Mechanisms

The predictive power of these biomarkers stems from their roles in distinct biological processes. PD-L1 expression represents a mechanism of adaptive immune resistance, where tumors exploit the PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint pathway to suppress T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity [15] [14]. In contrast, MSI/dMMR and TMB are both rooted in genomic instability. dMMR leads to a hypermutated phenotype, particularly at microsatellite regions, generating frameshift mutations and a high burden of immunogenic neoantigens that create an inflamed tumor microenvironment rich in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes [16]. TMB reflects the total number of mutations in the tumor genome, which correlates with the potential for neoantigen formation and subsequent T-cell recognition [14].

Diagram 1: Biomarker interplay in immunotherapy response. The diagram illustrates how dMMR/MSI-H and high TMB contribute to neoantigen formation, leading to T-cell activation and subsequent PD-L1 upregulation, which is targeted by checkpoint inhibitors.

Differential Predictive Value for Treatment Regimens

Emerging evidence suggests that these biomarkers may have differential predictive value depending on the therapeutic regimen. Exploratory analyses from the CheckMate 142 study in MSI-H/dMMR metastatic colorectal cancer revealed that higher expression of inflammation-related gene expression signatures was associated with improved response and survival with nivolumab monotherapy. In contrast, higher TMB, tumor indel burden (TIB), and degree of microsatellite instability were more strongly associated with efficacy with nivolumab plus ipilimumab combination therapy [17]. This suggests that for combination therapy, tumor antigenicity may be a more critical determinant of efficacy than the baseline inflammatory tumor microenvironment [17].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

PD-L1 Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Protocol Overview: PD-L1 expression is quantitatively measured using IHC on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue sections [12] [18].

Key Steps:

- Tissue Sectioning: Cut FFPE tissue into 4-5 μm sections and mount on slides.

- Deparaffinization and Antigen Retrieval: Use heat-induced epitope retrieval methods to unmask antigens.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Apply FDA-approved clones (e.g., 22C3 pharmDx, 28-8 pharmDx, SP142, SP263) specific to PD-L1 under standardized conditions [12] [18].

- Detection: Use enzyme-conjugated secondary antibodies and chromogenic substrates for visualization.

- Scoring: Evaluate staining using standardized scoring systems:

MSI/dMMR Testing

Dual-Method Approach: MSI/dMMR status can be determined through two primary methods, often used complementarily.

IHC for MMR Protein Expression:

- Procedure: Perform IHC on FFPE sections for the four MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2).

- Interpretation: Loss of nuclear expression in tumor cells for one or more proteins indicates dMMR. Specific patterns guide genetic testing (e.g., MLH1/PMS2 loss suggests sporadic MLH1 promoter hypermethylation) [16].

PCR-Based MSI Analysis:

- DNA Extraction: Isolate DNA from tumor and matched normal tissue.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify a standardized panel of mononucleotide and dinucleotide repeat markers (e.g., BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-24, MONO-27).

- Fragment Analysis: Compare fragment sizes between tumor and normal DNA. Instability at ≥2 markers (≥30% for pentaplex panels) defines MSI-H [16].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) panels now frequently include MSI calling algorithms, providing a high-throughput alternative [16] [19].

Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) Assessment

NGS-Based Measurement: TMB is calculated from genomic data as the total number of somatic mutations per megabase (mut/Mb) of the genome examined [11] [12].

Standardized Wet Lab Protocol:

- DNA Extraction: Extract high-quality DNA from FFPE tumor tissue and matched normal (when available).

- Library Preparation: Prepare sequencing libraries using comprehensive gene panels (e.g., TruSight Oncology 500, FoundationOne CDx) or whole exome sequencing [18] [19].

- Sequencing: Perform high-coverage sequencing on appropriate platforms (Illumina, Ion Torrent).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Alignment: Map sequencing reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38).

- Variant Calling: Identify somatic single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (indels) using validated pipelines.

- Filtering: Exclude known driver mutations, germline variants (using matched normal or population databases), and synonymous mutations.

- TMB Calculation: Divide the total number of nonsynonymous mutations by the size of the coding region targeted in megabases [18] [19].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for biomarker assessment. The flowchart outlines the key steps from sample processing to clinical reporting for PD-L1, MSI/dMMR, and TMB analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and technologies essential for conducting research on these established biomarkers.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Immunotherapy Biomarker Analysis

| Reagent/Technology | Specific Examples | Research Application | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| FDA-Approved IHC Assays | 22C3 pharmDx (Agilent), 28-8 pharmDx (Agilent), SP142 (Ventana), SP263 (Ventana) [12] [18]. | Quantifying PD-L1 expression on tumor and immune cells. | Standardized detection and scoring of PD-L1 protein expression; enables cross-study comparisons. |

| MMR IHC Antibodies | Anti-MLH1, Anti-MSH2, Anti-MSH6, Anti-PMS2 [16]. | Identifying loss of MMR protein expression. | Screening for dMMR status; patterns of loss guide further genetic testing. |

| NGS Panels | TruSight Oncology 500 (Illumina), FoundationOne CDx, Oncomine Comprehensive Assay Plus [18] [19]. | Comprehensive genomic profiling. | Simultaneous assessment of TMB, MSI, and specific genomic alterations from limited tissue. |

| MSI PCR Kits | Promega MSI Analysis System, Thermo Fisher MSI Assay [16]. | Standardized fragment analysis for MSI status. | Gold-standard validation of MSI status; often used to confirm NGS-based MSI calls. |

PD-L1, MSI/dMMR, and TMB represent the cornerstone of predictive biomarker testing for immunotherapy, each with distinct strengths and limitations. While these biomarkers have enabled more precise patient selection, their imperfect predictive accuracy highlights the complexity of tumor-immune interactions. Future directions involve developing integrated models that combine these established biomarkers with emerging ones—such as gene expression profiles, gut microbiome signatures, and host factors—to create more comprehensive predictive algorithms [13] [20]. The continued refinement and validation of these biomarkers are essential for advancing precision immuno-oncology and maximizing therapeutic benefit for cancer patients.

The advent of immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), has fundamentally transformed cancer treatment paradigms. However, a critical challenge remains: only 20–30% of patients achieve durable responses, highlighting an urgent need for reliable predictive biomarkers to guide therapeutic strategies [13] [21]. The field is rapidly evolving beyond single-analyte biomarkers toward integrated, multi-omics approaches. This guide objectively compares the performance of three emerging biomarker classes—Genomic, Proteomic, and Microenvironmental—in predicting immunotherapy response. Framed within the broader thesis of biomarker validation, this review provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comparative analysis of these platforms, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Comparative Analysis of Emerging Biomarker Classes

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, strengths, and limitations of the three primary emerging biomarker classes.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Emerging Biomarker Classes for Immunotherapy

| Biomarker Class | Key Examples | Predictive Utility | Clinical Validation Status | Key Strengths | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic | Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB), Microsatellite Instability (MSI) | Predicts neoantigen load and immunogenicity; tissue-agnostic approval for MSI-H [1]. | FDA approval for pembrolizumab in TMB-high (≥10 mut/Mb) and MSI-H tumors [1]. | Provides a quantifiable measure; foundational for companion diagnostics. | Limited accuracy as a standalone marker; spatial and temporal heterogeneity [1]. |

| Proteomic | Plasma protein signatures (e.g., VASN, PARD3, PTGES3), PD-L1 IHC | PD-L1 is most widely used; novel plasma models predict response in SCLC [22] [23] [21]. | Variable; PD-L1 used clinically but imperfect; novel signatures in validation phases (AUC >0.82) [22] [23]. | Reflects functional protein activity; liquid biopsy enables dynamic monitoring. | PD-L1 expression is dynamic and heterogeneous; assay variability [21]. |

| Microenvironmental | Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs), Tertiary Lymphoid Structures (TLS) | High CD8+ T cells and mature TLS correlate with improved response and survival [21]. | TILs are recognized in guidelines (e.g., ESMO); TLS is an emerging research biomarker [21]. | Captures the functional immune context; spatial organization is highly informative. | Requires tissue biopsy; complex standardization for scoring and analysis. |

Genomic Biomarkers

Genomic biomarkers analyze the DNA sequence of tumors to identify quantifiable genetic alterations that correlate with response to immunotherapy. The primary candidates include Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB), defined as the number of somatic mutations per megabase of DNA, and Microsatellite Instability (MSI), a condition of hypermutability resulting from defective DNA mismatch repair [1]. These biomarkers function as proxies for the tumor's neoantigen load, which determines its immunogenicity and susceptibility to immune attack.

Table 2: Experimental Data for Key Genomic Biomarkers

| Biomarker | Cancer Type | Therapeutic Context | Reported Performance | Source / Trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMB (≥10 mut/Mb) | Various solid tumors | Pembrolizumab monotherapy | ORR: 29% in TMB-high vs. 6% in TMB-low | KEYNOTE-158 [1] |

| TMB (≥20 mut/Mb) | Pan-cancer | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors | Improved survival (HR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.47-0.58) | Gandara et al. [1] |

| MSI-H/dMMR | Tissue-agnostic | Pembrolizumab | ORR: 39.6%; 78% with durable responses | KEYNOTE-016/164/158 [1] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for TMB and MSI Analysis:

- Sample Acquisition: Obtain tumor tissue via biopsy (or use stored FFPE samples) and a matched normal sample (e.g., blood or saliva).

- DNA Extraction: Use commercial kits (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy) to extract high-quality genomic DNA from both tumor and normal samples. Quantify DNA using fluorometry.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries using comprehensive gene panels (e.g., > 1 Mb) or whole-exome kits. This involves DNA shearing, adapter ligation, and target enrichment. Sequence on an NGS platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Alignment: Map sequencing reads to a reference human genome (e.g., GRCh38).

- Variant Calling: Identify somatic mutations (SNVs, indels) by comparing tumor and normal BAM files.

- TMB Calculation: Filter out driver mutations and synonymous variants. TMB is calculated as the total number of non-synonymous mutations divided by the size of the coding region targeted in megabases.

- MSI Status: Analyze the length distribution of microsatellite loci in the tumor sample compared to the normal sample to detect instability.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Genomic Biomarker Research

| Research Reagent | Function | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Iserts high-quality, PCR-amplifiable DNA from FFPE or fresh tissue. | QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen) |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Facilitates the preparation of sequencing-ready libraries from input DNA. | Illumina DNA Prep with Enrichment |

| Comprehensive Cancer Panel | A probe-based panel for hybrid capture to prepare libraries for TMB analysis. | SureSelect XT HS Pan-Cancer Panel (Agilent) |

| Bioinformatic Pipeline | Software for the analysis of NGS data, including alignment and variant calling. | Illumina Dragen Bio-IT Platform |

Proteomic Biomarkers

Proteomic biomarkers measure the expression, modification, and interaction of proteins, providing a direct readout of functional biological activity. While PD-L1 immunohistochemistry is the most clinically established proteomic biomarker, its predictive accuracy is limited [1] [21]. Emerging research focuses on plasma proteomic profiling to identify novel, non-invasive predictive signatures. For instance, a recent study in small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) developed a model based on three plasma proteins—VASN, PARD3, and PTGES3 (the VPP model)—which demonstrated robust performance in predicting response to anti-PD-L1 plus chemotherapy [22] [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Mass Spectrometry-Based Plasma Proteomic Profiling:

- Sample Collection and Preparation: Collect peripheral blood into EDTA tubes. Centrifuge to isolate plasma, which is then aliquoted and stored at -80°C. Deplete high-abundance proteins (e.g., albumin, IgG) using immunoaffinity columns to enhance the detection of lower-abundance proteins.

- Protein Digestion: Denature plasma proteins, reduce disulfide bonds, and alkylate cysteine residues. Digest proteins into peptides using trypsin.

- Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS):

- Chromatography: Separate the complex peptide mixture via reverse-phase liquid chromatography.

- Mass Spectrometry: Analyze eluted peptides using a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Thermo Fisher Orbitrap). The instrument operates in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode, cycling between a full MS1 scan (for peptide quantification) and subsequent MS2 scans (for peptide identification via fragmentation).

- Data Analysis and Model Building:

- Protein Identification & Quantification: Process raw data using software (e.g., MaxQuant) to identify proteins and perform label-free quantification (LFQ).

- Statistical Analysis & Machine Learning: Conduct bioinformatic analyses (e.g., pathway enrichment). Use machine learning algorithms like LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) regression on the proteomic data from a discovery cohort to build a predictive model, which must then be validated in an independent cohort [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Proteomic Biomarker Research

| Research Reagent | Function | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| Plasma Prep Tube | Collects and separates plasma from whole blood for biomarker analysis. | BD Vacutainer EDTA Tubes |

| Protein Depletion Column | Removes abundant proteins to enhance detection of low-abundance biomarkers. | ProteoPrep Immunoaffinity Albumin & IgG Depletion Kit (Merck) |

| Trypsin, Sequencing Grade | Enzymatically digests proteins into peptides for LC-MS/MS analysis. | Trypsin Gold, Mass Spectrometry Grade (Promega) |

| LC-MS/MS System | High-resolution system for separating and analyzing complex peptide mixtures. | Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher) |

Microenvironmental Biomarkers

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is the ecosystem surrounding a tumor, and its composition is a critical determinant of immunotherapy efficacy. Key biomarkers include CD8+ Cytotoxic T Cells, the primary effector cells for killing cancer cells, and Tertiary Lymphoid Structures (TLS), which are organized aggregates of immune cells that form ectopically in tumors and serve as hubs for initiating and sustaining anti-tumor immunity [21]. The density, location, and functional state of these components provide profound insights into the tumor's immune status.

Table 5: Experimental Data for Key Microenvironmental Biomarkers

| Biomarker | Cancer Type | Therapeutic Context | Reported Performance | Source / Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD8+ T Cells (High Density) | NSCLC | PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors | Correlates with improved survival and response. | Frontiers in Immunology [21] |

| Tertiary Lymphoid Structures (TLS) | NSCLC | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors | Presence correlates with improved patient survival and response to ICIs. | Frontiers in Immunology [21] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Multiplex Immunofluorescence (mIF) and Digital Pathology for TME Analysis:

- Tissue Sectioning: Cut formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue blocks into sequential sections (4-5 μm thick).

- Multiplex Immunofluorescence Staining: Use automated staining platforms and tyramide signal amplification (TSA) based kits to sequentially label multiple antigens on a single tissue section. A typical panel might include antibodies against:

- CD8 (Cytotoxic T cells)

- CD4 (Helper T cells)

- CD20 (B cells)

- Pan-CK (Tumor cells)

- DAPI (Nuclear counterstain)

- Multispectral Imaging: Scan the stained slides using a multispectral microscope (e.g., Akoya Vectra or PhenoImager). This system captures the fluorescence spectrum at each pixel, allowing for the separation of overlapping signals.

- Image and Data Analysis:

- Spectral Unmixing & Cell Segmentation: Use image analysis software (e.g., Akoya inForm, HALO) to unmix the multispectral images, identify individual cell nuclei (DAPI), and classify each cell based on marker expression (phenotyping).

- Spatial Analysis: Calculate cell densities and perform spatial analyses, such as determining the proximity of CD8+ T cells to tumor cells (Pan-CK+). TLS are identified as organized clusters of CD20+ B cells surrounded by CD4+/CD8+ T cells.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 6: Essential Reagents for Microenvironmental Biomarker Research

| Research Reagent | Function | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex IHC/IF Antibody Panel | A pre-optimized panel of antibodies for simultaneous detection of multiple cell types. | Opal Polychromatic IHC Kits (Akoya Biosciences) |

| Automated Staining System | Provides consistent and reproducible staining for multiplexed assays. | BOND RX Research Stainer (Leica Biosystems) |

| Multispectral Imaging System | A slide scanner that captures spectral data for precise fluorescence unmixing. | Vectra POLARIS (Akoya Biosciences) |

| Spatial Biology Analysis Software | Software for cell phenotyping, density quantification, and spatial analysis. | HALO Image Analysis Platform (Indica Labs) |

The Future of Biomarker Discovery: AI and Multi-Omics Integration

The limitations of single-biomarker approaches are driving the field toward multi-omics integration and artificial intelligence (AI). AI and machine learning (ML) are accelerating biomarker discovery by mining complex datasets to identify hidden patterns and improve predictive accuracy [24] [3]. For example, machine learning models like SCORPIO and LORIS have demonstrated superior performance (AUC values up to 0.84-0.85 in select studies) compared to traditional single-biomarker methods like PD-L1 [13]. These models integrate diverse data types—genomic, proteomic, digital pathology images, and clinical features—to generate a holistic "molecular fingerprint" of a patient's disease [20]. This Comprehensive Oncological Biomarker Framework aims to move beyond static snapshots to dynamic, predictive models that can guide truly personalized immunotherapy regimens. The global biomarkers market, projected to grow from $62.39 billion in 2025 to $104.15 billion by 2030, reflects the significant investment and expectation in these advanced technologies [25] [26].

The pursuit of reliable biomarkers to predict response to immunotherapy has represented a central challenge in oncology research. While immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and adoptive cell therapies like CAR-T have revolutionized cancer treatment, they benefit only a subset of patients, creating an urgent need for predictive biomarkers [27] [28]. Traditional approaches focused on single-parameter biomarkers such as PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden (TMB) have demonstrated limited predictive accuracy across diverse patient populations and cancer types [29] [30]. The complexity of tumor-host interactions, encompassing dynamic immune responses, microbial influences, metabolic reprogramming, and mechanical aspects of the tumor microenvironment (TME), necessitates a fundamental shift toward multi-dimensional assessment frameworks [31] [32].

The Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Immune Biomarkers Task Force has emphasized that due to the complexity of immune responses and tumor biology, a single biomarker is unlikely to sufficiently predict clinical outcomes to immune-targeted therapy [28]. Instead, the integration of multiple tumor and host parameters—including protein expression, genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic data—may be necessary for accurate prediction of clinical benefit. This paradigm shift recognizes cancer as a systemic disease influenced by host genomic diversity, environmental exposures, and complex host-tumor ecosystems that extend far beyond the tumor cell itself [32].

Limitations of Single-Parameter Biomarker Approaches

Single-parameter biomarkers have served as important initial tools for predicting immunotherapy response but face significant limitations in clinical application. PD-L1 immunohistochemistry suffers from lack of standardization in antibody clones, scoring systems, and expression thresholds across different cancer types [29] [30]. Additionally, PD-L1 expression exhibits dynamic temporal and spatial heterogeneity within tumors, making assessment from limited biopsy material potentially unrepresentative [29].

Tumor mutational burden (TMB), while valuable in certain contexts, shows limited predictive utility in malignancies with low mutation rates such as pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (typically <20 mutations per exome) [33]. The correlation between TMB and neoantigen load is imperfect, and the threshold for "high TMB" varies considerably across cancer types [33]. In direct comparative analyses, TMB demonstrated median time-dependent area under the curve (AUC(t)) values of 0.503-0.543 for predicting overall survival in ICI-treated patients, significantly underperforming compared to integrated models [30].

Table 1: Limitations of Conventional Single-Parameter Biomarkers

| Biomarker | Key Limitations | Predictive Performance | Technical Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD-L1 IHC | Spatial heterogeneity, dynamic expression | AUC ~0.65 for response prediction [29] | Lack of standardized antibodies/scoring systems |

| TMB | Limited utility in low-mutation cancers | Median AUC(t) 0.503-0.543 for survival [30] | Requires sufficient tissue, complex NGS platforms |

| MSI/dMMR | Applicable to limited cancer subtypes | High predictive value but in <5% of solid tumors | Specialized testing requirements |

| Single cytokine assays | Reflect momentary immune state only | Limited predictive value alone [27] | Dynamic fluctuations, lack of standardized thresholds |

The limitations of these single-parameter approaches become particularly evident when considering the multi-dimensional nature of antitumor immunity. Effective immune responses require a coordinated sequence of events including tumor antigen presentation, T cell activation, trafficking to tumor sites, and infiltration into the immunosuppressive TME—a process that cannot be captured by measuring any single parameter [27] [31].

Multi-Dimensional Biomarker Platforms: Technologies and Methodologies

Multiplex Immunohistochemistry/Immunofluorescence (mIHC/IF)

Multiplex IHC/IF technologies enable simultaneous detection of multiple biomarkers on a single tissue section, preserving spatial context and enabling characterization of immune cell communities within the TME [29]. The MICSSS (Multiplexed Immunohistochemical Consecutive Staining on Single Slide) technique employs repeated cycles of immunoperoxidase labeling, imaging, and dye elution followed by image alignment and integration [29]. Alternatively, Opal multiplex immunofluorescence uses tyramine signal amplification (TSA) with fluorescent signals covalently bound to antigens, allowing antibody stripping via microwave heating while preserving fluorescence signals, enabling 7-9 color staining [29].

These platforms permit comprehensive immune profiling within the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME), including assessment of immune cell density, cellular composition, functional states, and cell-cell interactions [29]. When compared to traditional IHC, mIHC/IF demonstrated superior predictive accuracy for ICI response (AUC 0.79 vs 0.65 for PD-L1 IHC alone) and higher positive predictive value with lower false-positive rates [29].

Multi-Omics Integration Strategies

Integrated multi-omics approaches combine genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and microbiomic datasets to capture the complexity of tumor-host interactions. Genomic analyses now extend beyond TMB to include neoantigen quality, HLA evolutionary divergence (HED), and non-SNV sources of neoantigens (frameshifts, splice variants, gene fusions) that may generate more immunogenic epitopes [33].

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) enables deconvolution of immune cell populations within the TME and identification of T cell exhaustion signatures (e.g., LAG3, TIM3, TOX, NR4A) that predict CAR-T failure [33]. Metabolomic profiling reveals immunosuppressive metabolites like lactate in AML microenvironments and succinate accumulation in CLL that drives T cell dysfunction through epigenetic silencing of effector genes [33].

Microbiome analysis through 16S rRNA sequencing and metagenomics identifies microbial signatures predictive of immunotherapy response. Enrichment of Faecalibacterium correlates with superior CAR-T expansion, while Enterococcus dominance associates with increased CRS severity [33]. Microbial metabolites like butyrate enhance CAR-T stemness through HDAC inhibition [33].

Table 2: Multi-Omics Technologies for Biomarker Discovery

| Technology Platform | Key Parameters Measured | Methodological Considerations | Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq | Immune cell heterogeneity, T cell exhaustion signatures | Requires fresh tissue, high cost, computational complexity | Identifying resistance mechanisms to CAR-T therapy [33] |

| Spatial transcriptomics | Gene expression within tissue architecture, immune cell localization | Preserves spatial context, lower resolution than scRNA-seq | Mapping immune cell niches in classical Hodgkin Lymphoma [33] |

| Metabolomic profiling | Lactate, succinate, arginine levels in TME | Rapid metabolite turnover, requires immediate sample processing | Predicting CAR-T persistence via plasma arginine levels [33] |

| Microbiome sequencing | Gut microbiome composition, functional potential | Confounded by medications, diet, sample collection variables | Modulating ICI response via fecal microbiota transplantation [34] |

Machine Learning-Based Integrative Models

Machine learning algorithms can integrate diverse data types to generate predictive models of immunotherapy response. The SCORPIO system utilizes routine blood tests (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel) and clinical characteristics to predict ICI efficacy across diverse cancer types [30]. Developed on data from 9,745 ICI-treated patients across 21 cancer types, SCORPIO achieved median time-dependent AUC values of 0.763-0.759 for predicting overall survival at 6-30 months, significantly outperforming TMB [30].

These models employ ensemble algorithms with soft voting and five-fold cross-validation for hyperparameter optimization, trained to predict either overall survival or clinical benefit (defined as complete response, partial response, or stable disease ≥6 months) [30]. The incorporation of routinely available clinical and laboratory data provides a practical advantage over more complex genomic assays, with potential for broader implementation across diverse healthcare settings.

The Tumor Microenvironment as a Multi-Dimensional Ecosystem

Mechanical Properties of the TME

The mechanical aspects of the TME represent an underappreciated dimension influencing immunotherapy response. Tumor stiffness creates physical barriers that impede drug penetration and immune cell infiltration through compressed vasculature and dense extracellular matrix [31]. Mechanical forces activate mechanosensitive signaling pathways (YAP/TAZ, integrin signaling) that promote drug efflux and confer therapy resistance [31]. Additionally, stiff matrices recruit immunosuppressive cells including M2 macrophages and regulatory T cells, further inhibiting antitumor immunity [31].

The mechanical TME interacts bidirectionally with classic TME features—hypoxia and acidity drive matrix remodeling through HIF-1α and TGF-β signaling, increasing stromal stiffness that in turn exacerbates hypoxic conditions through vascular compression [31]. This creates a feed-forward loop that reinforces the immunosuppressive TME.

Figure 1: Multidimensional Interactions Within the Tumor Microenvironment (TME). The TME represents a complex ecosystem where mechanical, immune, metabolic, and microbial factors interact bidirectionally to influence therapy response.

Microbial Influences on Antitumor Immunity

The human microbiome constitutes a crucial component of the tumor-host interface, with particular importance for immunotherapy outcomes. Approximately 20% of malignancies are associated with dysbiosis of human microbiomes, mediated through chronic inflammation, immune modulation, and metabolic reprogramming [34]. Specific pathogens like Helicobacter pylori and Fusobacterium nucleatum are established carcinogens, while commensal microbes significantly influence therapy responses [34] [35].

In preclinical models, selective菌群移植 (FMT) from ICI responders to non-responders can restore therapeutic efficacy, with III期临床试验 demonstrating that standardized fecal microbiota capsules achieve disease control rates of 41.2% in previous non-responders [34]. Microbial metabolites including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate enhance CAR-T cell stemness through epigenetic mechanisms and improve oxidative phosphorylation capacity [33] [35]. Engineering of microbial communities represents a promising therapeutic strategy, with synthetic microbial consortia successfully reversing tumor-associated immune dysregulation in animal models [34].

Experimental Workflows for Biomarker Validation

Analytical Validation Frameworks

The validation of biomarker assays requires rigorous assessment of pre-analytical and analytical variables according to established regulatory guidelines. The SITC Immune Biomarkers Task Force Working Group 1 (WG1) has developed comprehensive frameworks addressing pre-analytical factors (sample collection, processing, storage), analytical performance (specificity, sensitivity, reproducibility), and clinical validation requirements [28]. For multiplex immunofluorescence assays, this includes standardization of antibody validation, tissue processing, signal quantification, and image analysis algorithms to ensure inter-laboratory reproducibility [29].

Fit-for-purpose validation approaches tailor stringency requirements to the intended application, with more rigorous standards required for predictive biomarkers guiding treatment decisions compared to exploratory research assays [28]. For complex assays like mIHC/IF, key validation parameters include antibody cross-reactivity assessment, signal-to-noise optimization, autofluorescence correction, and validation of automated analysis pipelines [29].

Figure 2: Multiplex Immunohistochemistry/Immunofluorescence (mIHC/IF) Experimental Workflow. The process involves standardized pre-analytical sample processing, sequential staining with antibody elution, multispectral imaging, computational analysis, and clinical validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Multidimensional Biomarker Analysis

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplex Imaging Platforms | OPAL Polaris, CODEX, Imaging Mass Cytometry | Spatial immune profiling, cell-cell interaction analysis | Antibody validation, spectral overlap compensation [29] |

| Single-Cell Analysis Platforms | 10X Genomics Chromium, BD Rhapsody, Smart-seq2 | Immune cell heterogeneity, T cell receptor repertoire | Cell viability critical, index hopping controls [33] |

| Metabolomic Profiling | LC-MS/MS, NMR spectroscopy | Assessment of oncometabolites, nutrient availability | Rapid sample processing required, stable isotope tracing [36] |

| Microbiome Analysis | 16S rRNA sequencing, shotgun metagenomics | FMT donor screening, microbial source tracking | Contamination controls, biomass assessment [34] |

| Computational Tools | CIBERSORT, xCell, Digital Twins | Microenvironment deconvolution, therapy response modeling | Reference signature optimization, batch effect correction [33] |

Future Directions and Clinical Translation

The field of biomarker development is rapidly evolving toward increasingly integrated assessment frameworks. Digital twin technologies—personalized computational models that integrate genomic, transcriptomic, and immunologic data—are emerging as dynamic platforms for simulating treatment responses and optimizing therapeutic strategies [33]. Longitudinal monitoring approaches using liquid biopsies (ctDNA, CTCs, exosomes) enable real-time assessment of tumor dynamics and immune responses, supporting adaptive treatment personalization [33].

Clinical trial designs are similarly evolving, with basket trials incorporating multi-omics stratification and adaptive trial designs incorporating real-time omics feedback [33]. The successful clinical translation of these approaches will require addressing significant challenges in data heterogeneity across platforms, computational complexity, standardization of analytical pipelines, and establishment of ethical frameworks for data privacy and regulatory approval [33] [32].

The vision for the future involves moving beyond static, single-parameter biomarkers toward dynamic, multi-dimensional assessment frameworks that capture the complex interplay between tumors and their hosts. This approach acknowledges that effective antitumor immunity requires the successful coordination of multiple biological processes, and that therapeutic response is ultimately emergent from this complex system rather than determinable by any single molecular parameter. As these integrated models mature and undergo clinical validation, they hold the promise of transforming immunotherapy from a one-size-fits-all approach to a truly personalized precision medicine paradigm.

Biomarker Enrichment Strategies in Early-Phase Trial Design

In the era of precision medicine, biomarker enrichment strategies have become pivotal in early-phase clinical trial design, particularly in immuno-oncology. These strategies aim to identify patient subgroups most likely to respond to treatment, thereby accelerating drug development and increasing the probability of trial success. The validation of biomarkers to predict response to immunotherapy represents a critical focus in modern oncology research, addressing the challenge that only a subset of patients derives clinical benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors and other immunotherapeutic approaches. This guide compares the predominant biomarker enrichment strategies, providing researchers with a framework for selecting and implementing these designs in early-phase trials.

Core Biomarker Enrichment Trial Designs

Biomarker enrichment strategies in early-phase trials can be broadly categorized into several distinct designs, each with specific applications, advantages, and limitations. The choice of design depends on the strength of preliminary evidence for the biomarker, its prevalence, and the underlying scientific rationale.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Biomarker Enrichment Trial Designs

| Design Type | Key Principle | When to Use | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Design | Enroll only biomarker-positive patients [37] | Strong preliminary evidence that benefit is restricted to biomarker-positive subgroup [38] | Efficient signal detection; reduced sample size; increased probability of success in targeted population [39] [11] | Narrower regulatory label; requires validated assay; no information on biomarker-negative patients [37] |

| All-Comers Design | Enroll both biomarker-positive and negative patients without restriction [37] | Preliminary evidence regarding treatment effects in marker subgroups is unclear [38] | Allows retrospective biomarker analysis; avoids missing efficacy in unselected populations [37] | May dilute overall treatment effect if benefit is restricted to a subgroup; larger sample size required [37] |

| Adaptive Enrichment Design | Starts with all-comers population, then restricts enrollment based on interim analysis [39] [40] | Uncertainty about biomarker cut-off or which subgroups benefit; learning and confirming approach needed [39] | Flexibility to refine population during trial; avoids premature termination for full population [39] [40] | Statistical complexity; potential for false enrichment; requires careful planning of interim analyses [39] |

| Stratified Randomization | Enroll all-comers but randomize within biomarker subgroups [37] | Biomarker is prognostic; both low and high biomarker patients may benefit [37] | Removes confounding bias; ensures balanced arms for subgroup comparisons [37] | Requires larger sample size; complex trial logistics [37] |

Advanced Adaptive Designs for Biomarker Integration

Recent methodological advances have focused on adaptive designs that allow for biomarker threshold estimation and population refinement during the trial. These approaches are particularly valuable for continuous biomarkers where no validated cut-off exists at trial initiation.

Biomarker Enrichment and Adaptive Threshold (BEAT) Design

The BEAT design updates the estimated optimal biomarker threshold in blocks by maximizing a utility that balances the size of the biomarker-positive population and the treatment effect in that population [40]. This design allows flexible patient enrichment where biomarker-positive patients are enrolled in the next block, while biomarker-negative patients may be enrolled or excluded based on estimation precision and predictive probability of failure [40].

Key Methodological Components:

- Interim Analyses: Pre-specified interim analyses assess accumulating data to inform adaptations

- Decision Rules: Based on predictive probability of success at final analysis [39]

- Stopping Rules: Early termination for futility based on predictive probability for biomarker-positive patients [40]

- Bayesian Methods: Used for calculating posterior distributions and predictive probabilities [39]

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Adaptive Designs

| Design Feature | Classical Single-Stage Design | Two-Stage Adaptive Enrichment Design | BEAT Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of Correct Decision | Lower (benchmark) | Higher [39] | Highest [40] |

| Sample Size Efficiency | Less efficient | More efficient [39] | Most efficient [40] |

| False Enrichment Rate | Not applicable | Controlled [39] | Minimized [40] |

| Threshold Estimation Accuracy | Not applicable | Moderate | High with precision estimates [40] |

| Flexibility for Futility Stopping | Limited | Available for full population [39] | Available for both full population and subgroups [40] |

Experimental Protocols for Implementation

Protocol 1: Two-Stage Adaptive Biomarker-Guided Design

This protocol is adapted from the design proposed in the context of an oncology Proof of Concept (PoC) trial [39]:

- Stage 1 Enrollment: Recruit an initial cohort of patients (e.g., n=14) from the full population without biomarker restriction

- Interim Analysis (IA): Conduct when pre-specified number of patients have evaluable data

- Calculate predictive probability of success for full population

- If predictive probability < ηfutility, stop trial for futility

- If predictive probability > ηsuccess, continue to Stage 2 with full population

- If promising but inconclusive, identify biomarker subgroup using predefined criteria and continue with enriched population [39]

- Biomarker Threshold Identification: For continuous biomarkers, determine cutoff that divides patients into subgroups based on estimated probability of response to treatment [39]

- Stage 2 Enrollment: Recruit additional patients based on decision from IA

- Final Analysis: Evaluate treatment effect in final population using Bayesian methods with pre-specified decision criteria [39]

Protocol 2: BEAT Design Implementation

This protocol implements the Biomarker Enrichment and Adaptive Threshold detection method [40]:

- Blockwise Enrollment: Divide trial into multiple blocks (typically 3-5)

- Biomarker Response Modeling: Fit model (e.g., logistic regression) to relate biomarker to treatment response after each block [40]

- Utility Optimization: Calculate optimal biomarker threshold that maximizes utility function balancing subgroup size and treatment effect [40]

- Adaptive Enrollment: For next block:

- Enroll all patients above updated threshold

- Optionally enroll some patients below threshold based on estimation precision

- Futility Assessment: After each block, calculate predictive probability of success for biomarker-positive patients; stop if below threshold [40]

- Final Analysis: Classify all enrolled patients as biomarker-positive or negative based on final estimated threshold; test treatment effects accordingly [40]

Visualization of Adaptive Biomarker Trial Design

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for a two-stage adaptive biomarker-guided trial design:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of biomarker enrichment strategies requires specialized reagents and platforms for biomarker assessment and data analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biomarker-Driven Trials

| Reagent/Platform | Primary Function | Application in Immunotherapy Trials |

|---|---|---|

| PD-L1 IHC Assays (22C3, 28-8, SP142, SP263 clones) [11] | Detect PD-L1 protein expression in tumor tissue | Patient selection for PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors; cutoff determination [11] [21] |

| NGS Panels | Assess tumor mutational burden (TMB), microsatellite instability (MSI), specific mutations [11] | Identify patients with TMB-H (≥10 mut/Mb) or MSI-H tumors for immunotherapy [11] |

| ctDNA/Liquid Biopsy Assays | Detect tumor-derived DNA in blood [1] [21] | Dynamic biomarker monitoring; assessment of tumor heterogeneity [1] |

| Multiplex Immunofluorescence | Simultaneous detection of multiple immune cell markers (CD8, CD4, CD68, etc.) [21] | Quantify tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and spatial organization in tumor microenvironment [21] |

| Variance Stabilizing Normalization (VSN) | Data normalization to minimize cohort discrepancies [41] | Improve reproducibility of biomarker measurements across batches and cohorts [41] |

| Bayesian Analysis Software (e.g., Stan, JAGS) | Calculate posterior distributions and predictive probabilities [39] [40] | Interim decision-making for adaptive designs; futility analysis [39] |

Biomarker enrichment strategies in early-phase trial design represent a paradigm shift in immuno-oncology drug development. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that adaptive enrichment designs offer significant advantages over traditional fixed designs when biomarker uncertainty exists. These designs increase trial efficiency by focusing resources on patient populations most likely to benefit, while maintaining flexibility through pre-planned interim analyses.

The successful implementation of these strategies requires careful consideration of multiple factors: the strength of preliminary biomarker evidence, assay validation status, statistical operating characteristics, and operational feasibility. As immunotherapy research evolves, emerging approaches such as multi-omics biomarker integration, machine learning-based predictive models, and dynamic biomarker monitoring are likely to further enhance the precision of patient enrichment strategies.

Researchers should select enrichment designs based on their specific developmental context, recognizing that well-executed biomarker strategies can accelerate the delivery of effective immunotherapies to appropriate patient populations while reducing exposure to ineffective treatments in others.

The Biomarker Validation Pipeline: A Stepwise Framework from Analytical to Clinical Validation

The pre-analytical phase, encompassing all processes from sample collection to analysis, represents the most vulnerable stage in the total testing process and stands among the greatest challenges for laboratory professionals [42]. In the context of biomarker validation for predicting immunotherapy response, this phase takes on heightened importance. The accuracy and reliability of predictive biomarkers such as PD-L1 expression, tumor mutation burden (TMB), and gene expression profiles directly depend on rigorous pre-analytical controls [43] [21]. Unfortunately, pre-analytical activities, management of unsuitable specimens, and reporting policies lack full standardization and harmonization worldwide [42]. This variability introduces significant challenges for multi-center clinical trials and biomarker validation studies, where consistent sample handling across different sites is paramount for generating comparable, high-quality data.

The complexity of the pre-analytical phase is particularly evident in immunotherapy research, where biomarkers are derived from diverse sources including tissue, blood, and other bodily fluids [20] [21]. The integrity of these samples directly impacts the performance of downstream analytical techniques such as immunohistochemistry (IHC), ELISA, genomic sequencing, and emerging technologies like surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) [44] [20]. Even with advanced detection platforms, pre-analytical inconsistencies can compromise the predictive accuracy of biomarkers intended to guide immunotherapy treatment decisions [43]. As research moves toward multi-modal biomarker panels and liquid biopsy technologies, standardized pre-analytical protocols become increasingly critical for successful clinical implementation of immunotherapy response prediction tools [43] [20] [21].

Pre-Analytical Variables and Their Impact on Biomarker Integrity

Key Pre-Analytical Factors

The pre-analytical phase encompasses numerous variables that can alter biomarker stability and detection. Understanding and controlling these factors is essential for maintaining sample quality in immunotherapy research:

- Sample Collection Variables: The method of blood draw, including tourniquet application time, can alter the concentration of numerous analytes [42]. For tissue biopsies, sampling location (primary vs. metastatic sites) and collection methods introduce variability, particularly for biomarkers like PD-L1 that show spatial heterogeneity [21].

- Sample Timing: The diurnal variation in certain biomarkers and the collection point during disease progression or treatment can significantly impact results. Emerging research suggests that molecular progression detectable through liquid biopsy might precede anatomical progression, requiring precise timing for optimal predictive value [45].

- Sample Handling and Processing: Centrifugation conditions, temperature during transport and storage, and processing delays represent critical control points. Studies demonstrate that hemolysis affects lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) measurements, both potential biomarkers for immunotherapy response [42].

- Sample Identification and Labeling: Patient misidentification or improper specimen labeling can lead to erroneous clinical decisions. Standardized protocols for patient verification and sample labeling are fundamental pre-analytical requirements [46].

Impact on Downstream Analytical Performance

Pre-analytical inconsistencies directly impact the performance of analytical techniques used in biomarker detection. Research on ELISA assays demonstrates how matrix effects and sample handling influence results. One study evaluating ELISA performance for urinary biomarkers found that only 3 of 11 commercially available tests passed accuracy thresholds, with the majority exhibiting coefficients of variation >20% [47]. This disappointing performance was attributed to the urine matrix itself and/or presence of markers in various isoforms, highlighting how sample-specific factors degrade assay performance.

Similarly, pre-analytical factors affect advanced detection technologies. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), while offering approximately 1.5-2 orders of magnitude lower detection limits compared to fluorescence-based immunoassays, remains susceptible to pre-analytical variations [44]. The median limit of detection (LOD) for SERS-based immunoassays is 4.3 × 10−13 M compared to 1.5 × 10−11 M for fluorescence immunoassays, but both techniques suffer from challenges including non-specific protein binding and insufficient reproducibility that can be exacerbated by poor pre-analytical practices [44].

Table 1: Impact of Pre-Analytical Errors on Biomarker Detection Technologies

| Analytical Technique | Common Pre-Analytical Challenges | Impact on Biomarker Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Delayed fixation, improper fixative type and volume, fixation time | Altered antigen detection, particularly for PD-L1 expression [21] |

| ELISA | Sample matrix effects, hemolysis, improper storage | Reduced accuracy and precision; high coefficients of variation [47] |

| Genomic Sequencing | Delay in processing, improper storage conditions | Nucleic acid degradation affecting TMB and mutation detection [43] |

| Liquid Biopsy | Cellular lysis during collection, improper stabilizers | False positives in circulating tumor DNA analysis [21] |

| SERS | Non-specific binding, sample contamination | Reduced sensitivity and reproducibility despite low LOD [44] |

Standardization Strategies for Pre-Analytical Workflows

Implementing Quality Control Measures

Establishing robust quality control systems is fundamental for standardizing the pre-analytical phase in immunotherapy biomarker research. Several key strategies have demonstrated effectiveness:

- Automated Identification Systems: Implementing barcode ID systems prevents specimen misidentification and inaccurate labeling, reducing errors at the point of collection [46]. Automated systems for identifying, storing, and tracking samples can eliminate errors at the front end while reducing labor intensity compared to manual implementation.

- Standardized Procedures: Development and adherence to standardized protocols for patient preparation, sample collection, transport, handling, storage, and preparation for testing should represent a major focus [42]. This includes specific guidelines for blood collection tubes, centrifugation parameters, and aliquot preparation.

- Comprehensive Documentation: Specific software developed for recording pre-analytical errors enables harmonization of incident reporting practices within the same laboratory and across national and international laboratories [42]. Systematic recording of pre-analytical errors is highly favorable for identifying recurring issues and implementing corrective actions.

- Rejection Criteria Establishment: Clear, standardized criteria for sample rejection based on defined quality parameters help maintain consistency across studies and clinical sites [42]. This includes specifications for hemolysis indices, lipemia, icterus, and clot formation.

Addressing Sample-Specific Challenges

Different sample types present unique pre-analytical considerations that must be addressed in standardized protocols:

- Tissue Samples: For solid tumor biopsies intended for PD-L1 staining or genomic analysis, standardized fixation protocols are critical. Cold ischemia time (time between tissue collection and fixation) should be minimized, with fixation typically in 10% neutral buffered formalin for defined durations based on tissue size [21].

- Liquid Biopsies: Blood samples for circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis require specific collection tubes with stabilizers to prevent white blood cell lysis and genomic DNA contamination. Consistent centrifugation protocols are essential for plasma preparation without cellular contamination [21].

- Urine Samples: Studies evaluating ELISA performance in urine highlight the particular challenges of this matrix, including variable pH, protein concentration, and the presence of proteases that can degrade protein biomarkers [47]. Standardized collection with protease inhibitors and pH stabilization is recommended.

Experimental Approaches for Evaluating Pre-Analytical Variables

Methodologies for Assessing Pre-Analytical Factors

Rigorous experimental approaches are necessary to quantify the impact of pre-analytical variables on biomarker stability and detection. Key methodological considerations include:

- Stability Studies: Systematic evaluation of biomarker stability under various storage conditions (temperature, duration) and processing delays. The study by Cuhadar et al. assessed the stability of common biochemical parameters in serum separator tubes with or without gel barrier subjected to various storage conditions, providing evidence-based guidelines for sample handling [42].

- Interference Testing: Controlled studies evaluating the impact of common interferents like hemolysis, lipemia, and icterus on biomarker detection. Koseoglu et al. investigated effects of different hemolysis degrees on common biochemical parameters, finding clinically significant differences for LDH, AST, potassium, and total bilirubin even with visually undetectable hemolysis [42].

- Matrix Comparison Studies: Parallel testing of biomarkers across different sample matrices (serum vs. plasma; tissue vs. liquid biopsy) to establish equivalence or differences. Such studies are particularly relevant for liquid biopsy development where plasma-based biomarkers may replace tissue-based ones [21].

- Method Comparison Studies: Evaluation of the same biomarker across different analytical platforms to assess consistency. This approach is exemplified by studies comparing predictive accuracy of PD-L1 immunohistochemistry, tumor mutation burden, gene expression profiling, and combined biomarkers for immunotherapy response [43].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Pre-Analytical Variables

| Experimental Approach | Key Protocol Steps | Data Output |

|---|---|---|

| Biomarker Stability Testing | 1. Aliquot samples from single source2. Expose to different time/temperature conditions3. Analyze all samples in same run4. Compare results to baseline | Stability specifications (allowable time delays, storage conditions) |